A continuation of: Out of the Shadows: Rory O’Connor in the Easter Rising and After, 1916-9 (Part I)

An Informative Discussion

Ireland was at war and on dual fronts. The first was the official one, as part of which the country contributed men and munitions to the British campaigns in the fields of France and Flanders. But there was a second struggle, the one at home which grew in the shadows, waiting to emerge. By the start of 1918, these two theatres of war threatened to merge when the demand for extra resources on the Western Front made conscription for Ireland an attractive option for the British Government, if a very dangerous one, considering the strength of Irish feeling against such an imposition.

Valentine Jackson was working for the Rathdown Rural District Council, Co. Dublin, when an officer from the British Army – by the rank of Major, Jackson believed – stopped by, asking to see the man responsible for the city streets. Jackson led him to the desk of Rory O’Connor, the Engineer of Paving. After O’Connor assured his caller that anything said would be in confidence, the Major explained the reason for his visit, saying that:

…there would be extensive street fighting in Dublin if conscription were enforced and that they would mainly use tanks, some of them of a heavy type, in such fighting. He wanted O’Connor to give him a list of streets which would be unsafe for the heaviest tanks, on account of sewers and other undergrounds works.

Playing the part of a dutiful civil servant perfectly, O’Connor asked for more information on the vehicles in question, such as their weights and load distribution, to better assess which streets would be riskiest for them. These details the Major did not know, though he promised to provide them later. The two men chatted for a while on the finer points of urban combat before the Major left, “very well pleased with the interview,” according to Jackson, who apparently had been hovering about to witness the exchange.

The Major had apparently never asked himself why a pen-pusher would know so much about street fighting, particularly where Dublin was concerned. During this same period of uncertainty, O’Connor called in on Jackson’s own office, located in the same building.

He wanted my opinion on a proposal that in the event of an attempt to enforce conscription the water supply should be cut off from all the city military establishments.

Not for nothing was Dublin Corporation viewed by the British authorities as a hotbed of sedition. While sympathetic to O’Connor’s idea, Jackson did not think it practical, explaining that the British Army would surely be competent enough to restart water pipes in the event of them being blocked or cut. Besides, fire hydrants could be used with hose-lines to provide water if necessary.

This was a setback to O’Connor, but he remained:

…anxious to consider the matter further so we spent the next few days driving around the city barracks during which he noted the size and exact position of the various branch pipes together with their valves and fittings.[1]

Such contingencies proved unnecessary, for the Government thought better of the idea and cancelled its plans for conscription in Ireland. The two sides, in the form of the British state and the Irish Republican Army (IRA), had narrowly avoided a bloody showdown – and bloody it would undoubtedly have been. While discussing the situation with Michael Collins, while the threat of conscription still hovered in the air, Ernie O’Malley was handed notes detailing plans for the demolition of bridges, railways and engines throughout the country, all of which were signed by O’Connor as Director of Engineering for the IRA GHQ.[2]

Later, O’Malley would meet O’Connor, as one senior IRA figure to another. Like many, he would find himself intrigued by the other man’s looks and enigmatic personality. “Rory O’Connor talked with a sense of humour; the grooves tightening his cheek muscles while his eyes smiled,” he later wrote. “He always had what I called an interior look.”[3]

Plans for Plans

To O’Connor, the end of conscription as a potential flashpoint was but a delay in the conflict he had been working towards, even before the Easter Rising of 1916 had transmogrified the Irish public mood. The anxious peace that had settled over the country could not last indefinitely and, when the storm at last broke out, O’Connor and his comrades would be armed and ready.

At least, in theory.

If the British authorities were often woefully blind to the insurgency brewing right beneath their noses – as in the case of the Major discussing strategy with a disingenuously helpful clerk – then the rebel underground only reached a state of readiness through slow trial and painful error. In early 1920, O’Connor came to Jackson with another request: could he find a quiet place out of town in which to test some explosives recently raided from a British Army depot?

In response:

I selected a site by the east side of the Upper Reservoir at Roundwood then under construction, but on which work was suspended. The site was Corporation property, well away from any habitation and contained a couple of derelict houses.

Jackson joined O’Connor in testing out the pilfered goods. As no one came to investigate the six or seven blasts, he had evidently chosen the spot well. The same could not be said for the explosives, being of poor quality as they were. “O’Connor was disappointed,” Jackson later wrote. “He attributed the result to deterioration of the material.”[4]

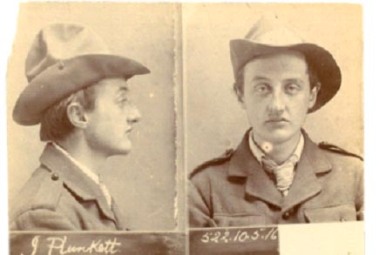

Still, one step at a time. Even if munitions were not easy to come by, then the IRA at least had an organisation structure to build on. Part of this was its Engineering Department, formed in the autumn of 1917 by O’Connor, and consisting of men with similarly technical minds. One of whom was Jack Plunkett, brother of the late 1916 Signatory, and a long-time friend of O’Connor. Together they pored over a large Ordinance Survey map of Ireland, plotting out the best methods of attack, with a particular emphasis on the railways lines that the British Army often used. These plans “Rory and I practically laid out alone,” according to Plunkett.

Even many years later, the memories of the time the two men spent together in shared enterprise could move him. “I would like to say a good deal about Rory but it hurts too much.”[5]

The 5th Battalion

Another team member was Liam Archer. Like O’Connor and Plunkett, he had been ‘out’ in Easter Week, and continued on in the IRA as a signal officer for the Dublin Brigade. Two years after the Rising:

When conscription was threatened in 1918 I was transferred to the staff of Rory O’Connor who had, I think, shortly before been made Director of Engineering. It was decided to organise a Company of Engineers under direct control of GHQ with the special mission of carrying out extensive sabotage of communications in the event of conscription being imposed.

From this, the 5th Dublin Battalion, or the Engineering Corps, was formed. While initially a Dublin matter, a two week-long course was set up for budding engineers from other IRA units in the country, with O’Connor, Plunkett and Archer acting as lecturers. “In time, we developed training in the use of explosives and demolition of rails and bridges and the mining of roads,” Archer recalled.

The shelving of conscription did nothing to change the IRA agenda: to fight British rule with every tool at hand. As this struggle intensified in Dublin and elsewhere in Ireland, O’Connor issued a prohibition against members of the 5th Battalion partaking in raids, ambushes or other standard IRA missions, however keen they were to do so. Such men were specialists, O’Connor ruled, and so were not to risk themselves in operations that ‘foot soldiers’ could do.

The commanders of the other four Dublin battalions did not disagree, as Archer described:

They considered, first, that the opportunities for such should be the preference of their units and, second, that it would be impossible for them that the 5th Battalion was carrying out, or had carried out, an operation in their areas, and that this fact could gravely endanger the success of their operations, and the safety of their personnel.

By keeping the 5th Battalion removed from the others, it was hoped that they would avoid getting their wires crossed. Even after O’Connor was promoted to another command and this prohibition of his officially lifted, the engineers of the 5th Battalion were only used when their particular skills were necessary.[6]

Life was becoming risky enough as it was.

Prison Plans

There was no formal declaration of war, no grand gesture, no Pearl Harbour or Fort Sumter or Gulf of Tonkin. Historians were to point to the Soloheadbeg Ambush in January 1919 as the trigger but that was merely the first in a series of incidents that slowly proliferated into a full-blown insurgency. Until then, the various IRA units limited their operations to one-offs, designed for a specific goal rather than the big picture.

In March 1919, Michael Lynch, O/C of the Fingal Brigade, answered the summons to the Dublin IRA headquarters at Gardiner Street, where O’Connor inquired about the amount of ‘gun cotton’ available. When Lynch asked him what for:

Rory informed me that the idea underlying his request was the blowing down of the boundary wall of Mountjoy Prison, in order to effect the release of some of our men, whose presence was vital to us in our organisation scheme and who had been sentenced to long terms of imprisonment in Mountjoy.

While Lynch had access to some such ‘gun cotton’, he was horrified at how much O’Connor wanted. “My God, man,” he said, “if you use that, you kill every prisoner in Mountjoy!”

All the amount needed was five to ten pounds, insisted Lynch. As an avid reader of the American Scientific Supplement, Lynch considered himself an expert on the matter. So did O’Connor, who insisted on the original figure stated. When the two men could not agree, the explosives notion was dropped. If Lynch was correct in his fears, then the Mountjoy residents were luckier than they could have known.

Others present at the meeting chipped in with their own ideas, the best being to waylay the van transporting the prisoner in mind – Robert Barton – to Dublin Castle for interrogation. As they had inside knowledge of this, the IRA men were able to plan for when and where: the van moving down Berkeley Road, to be blocked by a handcart with a forty-foot-long ladder fixed across, allowing those on standby to rush in.

When the day came, all worked as it should – save for one small snag.

“Barton was not in it,” Lynch recalled. “We indulged in a fair amount of bad language at our ill luck.”

Shortly afterwards, O’Connor met with Lynch again, showing him the letter from Barton that had been smuggled out. To O’Connor’s dismay, the prisoner was insisting that he escape on a certain date, which just happened to be a night of a full moon. Having already filed through the bars of his cell-door, Barton would make his way to the yard and then throw a handkerchief-wrapped brick over the outer wall to let the others know where he was.

From there, they were to help him over and out – easier said than done, as O’Connor griped.

Nonetheless, an opportunity was an opportunity.[7]

Breathless

On the 16th March 1919, the team of men from Dublin’s G Company gathered for their briefing by Peadar Clancy, their commanding officer, and O’Connor. The mission was drawn out on a blackboard as each participant was allocated his position on the Canal Bank, near the north-west corner of Mountjoy Prison. Some were to wait by the wall, hugging the shadows, while others paced the canal, batons in hand, in case any policemen came their way.

“Each man knew what was expected,” described Patrick J. Kelly, one of the group, “and the risk of a slip up on the part of anyone.”

At the chime of midnight, a rope-ladder was tossed up to the top of the wall. After all the talk of explosions and the drama of an open-air hijack, Barton’s liberation was to come by relatively simple means – that is, if all went as it should.

The first throw of the ladder failed to clear the twenty-foot height of the wall. The second succeeded and the man who had cast it waited with his hands on his end to steady the prisoner’s climb on the other side. However, as Kelly watched:

No strain came on the rope and we thought the plan on the inside had miscarried. We were wondering what to do next when a small stone was thrown over from the inside to let us know he was there and that something was amiss.

The other man shifted the rope-ladder into a better position, allowing Barton to make the climb to the top of the wall, from where he jumped down into the blanket outstretched for him by several of the others.

Unfortunately:

His weight was too much for the men holding it and he had a bad bump on the ground but escaped injury, and was soon on his way to the waiting car with Rory and Peadar.

O’Connor and Barton sat in the back, while Kelly got in besides the driver. With revolvers kept ready in the event of being pulled over by the police, the men drove through the darkened city to Donnybrook. O’Connor and Barton disembarked at Herbert Park and thanked the other two before walking out into the night.

The Irish revolution had scored a coup as “Bob Barton…was considered a very important man in the movement,” according to Kelly. Afterwards “it was very interesting to read the papers next day with their accounts of the escape and their theories as to the way it was managed.”[8]

One of the newspapers in question, the Evening Herald, was helped by how one of its staff, Michal Knightly, doubled as an IRA intelligence officer. O’Connor visited him in his office immediately after Barton’s flight, fully aware of its propaganda value. He was so breathless with excitement that Knightly had to wait while O’Connor rested in a chair before providing the scoop.[9]

Barton would later go on to put his name to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, more than two years later, in December 1921. Whether O’Connor would have been so keen to spring him had he known…but that is a different story.

Mountjoy Sensation

For the moment, the only story that mattered was the one Knightly had obligingly emblazoned in the papers of the Evening Herald:

THE SENSATION!

MR. R.C. BARTON. M.P., MISSING FROM MOUNTJOY

A POLITE LETTER

The last line was a reference to Barton’s cheeky parting-shot to his gaolers, a left-behind note in the style of a disappointed hotel guest: since he was leaving due to the discomfort of his accommodation, could his baggage be kept safe until sent for?[10]

Showing an evident delight at official discomfort, Knightly reported how:

The prison authorities…are “out of their minds over the whole affair,” and “at their wits’ ends” to know how the prisoner escaped.”[11]

Thirteen days later, the Evening Herald would have a similar story to tell. Like every good sequel, this one was bigger and more dramatic than before:

MOUNTJOY SENSATION

20 SINN FEIN PRISONERS ESCAPE

If the secrets behind Barton’s flight had remained as such, then the prison-break on the 29th March 1919, conducted brazenly in broad daylight, was anything but a mystery:

It appears that some of their number suddenly turned on the wardens who were in charge of them, and held them down while their comrades were arranging a rope ladder over a thirty-foot wall…the first thing the outside public noticed was the extraordinary spectacle of men sliding down a rope from the top of the jail wall to the canal bank.[12]

“The escape exceeded our most sanguine expectations,” recalled one of the escapees, Piaras Béaslaí, who credited O’Connor and Dick McKee, the O/C of the Dublin IRA Brigade, with the planning of the feat. But it had initially been touch and go, when a sudden snowstorm almost cancelled the daily allotment of recreation outside in the yard. Thankfully, the weather cleared in time for exercise-hour to go ahead at 3 pm.

A prisoner signalled from a window to the IRA watchman on Claude Road that the escapees-to-be were in place. When a whistle was sounded from the outside, the prisoners dashed for the designated part of the wall, while a rope-ladder appeared at the top and came down for them to climb. Once outside, the freed men ran along the canal bank to where a rescue party were waiting with bicycles to take them into town, where they were practically home safe, according to Béaslaí:

The moment they got out in the streets among the people they were made safe, for everybody befriended them. Such was the famous daylight escape from Mountjoy, which seemed the culmination of a series of bloodless triumphs for the Irish Volunteers.[13]

“How the ladder came to be fastened is a mystery,” added the Evening Herald. If the item in question was the hero of the hour, then it was also the sole casualty, being found discarded next to the canal. “It is now in the hands of the authorities.”[14]

O/C Escapes

Replacing the lost item became a priority, for there were other Irishmen languishing in captivity as political prisoners, among being Béaslaí again, who did not enjoy his liberty for long before being rearrested while cycling in Finglas village. The prison authorities learnt their lesson by transferring Béaslaí out of Ireland and to Strangeways, Manchester, to deter any further escapes. Béaslaí was not cowed, instead remaining in surreptitious contact with Michael Collins, the two engaging in a long-distance discourse on the best way to spring Béaslaí once more.[15]

To this end, Collins dispatched O’Connor to England. A coded letter to Austin Stack, another inmate in Strangeways, was signed from his “loving cousin Maud”, assuring him that “we are all busy preparing for the examination. Professor Rory has arrived. He is a very nice man.”[16]

To this end, Collins dispatched O’Connor to England. A coded letter to Austin Stack, another inmate in Strangeways, was signed from his “loving cousin Maud”, assuring him that “we are all busy preparing for the examination. Professor Rory has arrived. He is a very nice man.”[16]

Even if the past two rescues had been roaring successes – save for Barton’s spectacles, which had fallen off as he cleared the wall – those responsible were not going to rest on their laurels. As a process, prison-breaking would be inspected, improved and, as much as possible, perfected.

O’Connor relished the challenge. Dubbed the ‘O/C. Escapes’ by Jack Plunkett, he “frequently talked to me about it and he got not only pleasure but amusement out of it.”

A replacement ladder was procured, after first being tested for the lightness of its rope, balanced with weights at the end. In delegating Plunkett for such work:

Rory, while being extremely reticent, gave me all the information I needed to obtain the necessary material and as was the habit in those times, I always refrained from asking unnecessary questions.

These tight lips earned the respect of another consummate professional. “I notice your staff don’t ask any questions,” Dick McKee told O’Connor approvingly.

Strangeways

By the end of his investigation, Plunkett could provide a finished product that, while formidable, presented a practical challenge:

The Strangeways rope-ladder was very bulky, as it had wooden rings and two pairs of restraining ropes, one pair outside and one pair inside the wall, and it had to be carried through Manchester on a handcart with a piece of sacking thrown over it.[17]

The first date for the rescue, the 11th October 1919, was postponed when the ladder in question did not arrive in time. A message hidden in a pot of jam to Strangeways alerted the Irish captives that the next attempt was to be on the 25th.

As with Mountjoy, the rescue team selected a particular section of the wall, this one being next to a street with no houses and thus less civilians to get in the way. All the same, members of the Manchester IRA company, formed from Irish émigrés in the city who were willing to do their part for the cause, stood at either end to block it off, while two more paced the wall, disguised as window-cleaners.

“When everything was in readiness,” described Patrick O’Donoghue, the Manchester O/C, “Rory O’Connor blew a whistle which was the pre-arranged signal and this signal was answered from inside by one of the prisoners.”

The new, improved rope-ladder was thrown up but failed to fall down low enough on the other side for the inmates to reach. Two more attempts were made to no avail and, just when all looked lost, Peadar Clancy – who had also come over from Dublin – quickly placed an extension ladder against the wall and climbed to shift the rope one into place:

When this was done Austin Stack was the first man to come over the wall in safety. Béaslaí was next and he got stuck against the wall half way up because his other escaping comrades were trying to use the rope at the same time as he was endeavouring to make the ascent. It was realised that only one man could climb the rope at a time.[18]

Six men altogether got over, including Stack and Béaslaí, though the latter did not find it as easy as the last occasion, cutting his hand to the bone on the rope as he slid down. A waiting taxi took him and the other five to a safe-house, where they stayed for a week before he and Stack were taken by train to Liverpool, and from there to Dublin.

A friendly crewman allowed the pair to bunk inside his ship’s forecastles. “The other sailors showed no curiosity; they were used to such smugglings,” Béaslaí noted. After they disembarked at Sir John Rogerson’s Quay in the morning, they were informed by the driver sent to meet them, Joe O’Reilly – one of Collins’ ‘Squad’ – about how a police detective had been shot and wounded the previous night in St Stephen’s Green.[19]

There was, after all, a war still one, one that was creeping further and further into the open.

Narrow Disaster

‘Bloodless triumphs’, Béaslaí had called these kind of daring exploits, but that was not a state that could last for long. One Sunday morning, in September 1920, the Engineering Department arranged for a demonstration of their work on the Kilmashogue Mountain. The night before and again on the morning, Plunkett received word that the British were aware of their planned activities. Though he passed the warning on to O’Connor, the session went ahead anyway.

On the mountainside, the men exploded several small charges. As well as O’Connor and Plunkett, Richard Mulcahy, the IRA Chief of Staff, was present, along with Archer and several others. More participants had been expected, including two companies’ worth of men from the 5th Battalion. When some time had passed and those absent were still nowhere to be seen, the rest decided to proceed anyway, detonating about eight or nine bombs.

“Between two of these explosions we heard quite a fusillade of shots and later on several more which we found difficult to account for,” Plunkett remembered.

Despite the prior warnings, the men failed to put two and two together, and did nothing more than send out one of their number downhill to investigate before continuing. The engineers got a little too involved in their work, and disaster was narrowly averted when, according to Plunkett:

…one of the charges which had a large stone on top of it, was fired, the stone went straight up in the air and came down almost on the spot where one man, who had stood too close, had thrown himself down with the fright.

So near to him was the stone when it fell that I was able to touch it and the man’s leg with one hand. The stone which weighed about 30 lbs. was almost completely buried in the earth. No one was hurt.

When the first runner did not come back, a second was dispatched after him – and quickly returned with urgent news.

Blood on the Mountain

The missing two companies had drawn up next to St Columba’s College, the agreed rendezvous point on the mountain, and the forty or so men were about to set off uphill to join the others when they were ambushed by a large number of Auxiliaries, the militarised branch of the RIC which the British Government had formed in response to an increasingly defiant Ireland.

They had been hiding on the grounds of St Columba’s College the night before, taking care to detain passers-by who might warn their targets. The unsuspecting IRA men were caught entirely off-guard when armed foes emerged from behind the walls of the college, demanding for them to put their hands up.

“I should mention that this was the very first operation carried out in Ireland by the Auxiliaries,” wrote Plunkett.

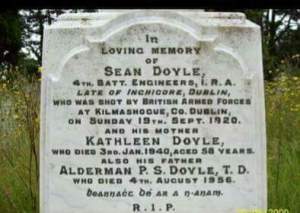

The remaining IRA men uphill promptly fled, with O’Connor and Mulcahy going in one direction, and Plunkett and Archer taking another. The Auxiliaries had already departed, taking with them the Irishmen they had caught as prisoners – save one. Plunkett and Archer came across a body on the mountainside. Seán Doyle had reached for the grenade in his pocket, only to be shot down by the Auxiliaries.

“The man’s shirt was completely soaked in blood,” Plunkett described. He did not recognise the corpse and so turned to his companion. “I asked Liam Archer to have a look at him and was quite disgusted that he wouldn’t.”[20]

Archer made no mention of that particular detail in his own account. To him, the day “was a lesson never to discount local knowledge,” as the warnings that morning about an enemy presence had been inexplicably ignored. It was a rude reminder to O’Connor and his colleagues that their war had a steep and unforgiving learning curve.[21]

A month later, in October 1920, O’Connor, McKee, Mulcahy, Collins and Oscar Traynor met in Gardiner’s Place, Dublin, to discuss the plight of the latest prisoner in need of rescue. Time was of the essence, as Kevin Barry was due to hang for his part in an ambush on British troops, and O’Connor resurfaced his idea of blowing a hole through the wall of Mountjoy in order to allow IRA men to rush in.

A month later, in October 1920, O’Connor, McKee, Mulcahy, Collins and Oscar Traynor met in Gardiner’s Place, Dublin, to discuss the plight of the latest prisoner in need of rescue. Time was of the essence, as Kevin Barry was due to hang for his part in an ambush on British troops, and O’Connor resurfaced his idea of blowing a hole through the wall of Mountjoy in order to allow IRA men to rush in.

Whether this would have led to the disaster Michael Lynch feared remains unknown. The plan proceeded far enough for men from the Dublin Brigade to get into position outside Mountjoy, in anticipation for the explosion, only for it to be cancelled for fear that the wardens would kill Barry rather than let him go.[22]

As if to signal the end of an era, Barry’s sentence went ahead and he was hanged on the 1st November 1920, the first such political execution since the Easter Rising. The days of thumbing the nose at hapless wardens seemed over, as the war for Irish independence entered a darker, less forgiving stage.

Eye for an Eye

Faced with this increased pressure, the IRA redoubled its efforts, outside Ireland as well as in. “Wholesale burnings were then taking place in Ireland,” as described by Michael O’Leary, “so that I am sure reprisals in England of a similar nature at this time would be considered very appropriate, as we believed ‘an eye for an eye’.”

As part of the Liverpool IRA Company, O’Leary was ideally placed for this sort of asymmetrical warfare. Paraffin oil, waste cotton-rags and other materials for lighting fires were gathered, the targets being the cotton warehouses and timber yards in the city. The men involved were summoned to Joseph’s Hall on Scotland Road, where they met O’Connor, whose duties once again involved sabotage, only this time on enemy soil and not just in Liverpool, but Manchester and London as well, so O’Connor informed them.

Clearly, the IRA GHQ was taking these overseas operations to heart, and O’Conor, having operated in England before, was the obvious choice to direct this latest theatre of the war. Gratified at the willingness of the men before him, O’Connor said he was off to Manchester but would return to see them in time for their mission to commence.

This he did so on the 26th November 1920, the day before the due date, and asked if there were any questions. O’Leary had one:

I asked him what would be our position after the fires, or how we were to act. He replied, “Keep quiet for a fortnight and repeat similar operations.”

O’Leary did not think this feasible. After all, most of them were already known to the authorities for their subversive activities and would surely be arrested before the two weeks passed. Instead, O’Leary wanted the Company to start anew immediately after the first attack, on the following morning, and begin a fresh wave of fires, this time against the shops in the city centre, and then moving on to the outskirts until finally brought low.

O’Connor turned down this suggestion, either because he did not wish to condone suicide and the waste of manpower or that he believed the men would still be at liberty after the fortnight for the second set of burnings as originally envisioned. O’Leary was not convinced but went ahead with the rest of the Company that night, on the 27th November.

He was gratified at how not a single man was absent when they assembled, before setting forth in teams of three to six towards their assigned targets. O’Leary was to be even more thrilled at their success and speed:

In less than 5 minutes a line of fire, 8 miles in length, from Seaforth to Gaston was started, resulting in the complete destruction of 14 cotton warehouses and 4 large timber yards.

The only failure was that of O’Leary and his group, being interrupted as they prepared the oil-soaked rags with which to burn down their allocated warehouse. O’Leary fired his revolver as two policemen wrestled with the man on watch, wounding one in the shoulder. Having gained the upper hand, he forced the pair against a wall and took aim, only for his gun to jam. The IRA men now fled into the night-time mist, with the shrill blasts of whistles behind them.[23]

Leaving a Legacy

O’Connor learnt about the success of the Liverpool mission while in Newcastle; at least, according to Liam McMahon, who had accompanied him from Dublin to help set up a Newcastle IRA company. The pair were watching a cinema newsreel when Liverpool came up, much to O’Connor’s approval. “Well, that is something,” he said to McMahon. “I hope Manchester will do as well.”[24]

O’Leary told a different version as, in his account, he reported straight to O’Connor, waiting in Joseph’s Hall, after escaping from the warehouse he had failed to destroy. O’Leary then took the morning train to Manchester. O’Connor could plan ahead all he wanted, but O’Leary knew Liverpool would be too dangerous for him now. As he had predicted, a wave of arrests followed, including his own, despite his efforts to put distance between himself and the scene of the crime.[25]

O’Leary could take comfort in how his troubles had not been in vain. “It is impossible to estimate the damage at the various fires, but a rough computation puts it at over a quarter of a million,” reported the news about Liverpool.

In addition, Daniel Ward, a 19-year-old labourer, had been killed that night after alerting some policemen to the four suspicious-looking men loitering in the doorway of a warehouse. In the resulting struggle, one of the men fired a revolver, hitting Ward with fatal results. This account matches O’Leary’s own in a number of details, but whether that is coincidental or if O’Leary omitted the blood on his hands when relaying his story years later is another of the period’s many unanswered questions.

Similar mass burnings had been intended to take place simultaneously in London and Manchester, but these proved to be damp squibs. On the same night as the Liverpool fires, police intercepted a band of men off White Cross Street, Aldersgate, London, outside a timber store. The cotton waste, scrap paper and paraffin they had on them would suggest identical intentions as in Liverpool, as would the gun they brandished at the policemen. Otherwise, London remained untroubled by the end of the 27th November.[26]

Manchester, likewise, had been underwhelming in performance, as few of the IRA there had been quite as keen as their Liverpudlian counterparts to undertake such a mission. “Rory O’Connor afterwards told me that he was very disappointed,” O’Leary recalled.[27]

Patrick O’Donoghue, as captain of the Manchester Company, would admit this inactivity on his men’s part, explaining that:

It was felt that our units were not sufficiently organised to carry out the destruction of warehouses on a large scale.[28]

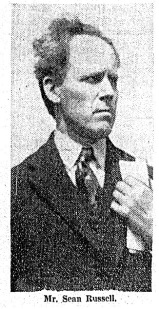

Despite this mixed success, O’Connor’s campaign of arson in Britain would live on in Republican memory. Sixteen years later, in the summer of 1938, two IRA veterans from the War of Independence, Seán Russell and Maurice Twomey, were sitting on the grounds of the Spa Hotel, New York, when the former reminisced about the damage O’Connor had helped inflict on the enemy homeland. Twomey was sceptical as to how useful this history lesson could be to them now but, to Russell, the late O’Connor had written the guidebook for his own bombing operation, to be undertaken in the following year.[29]

Despite this mixed success, O’Connor’s campaign of arson in Britain would live on in Republican memory. Sixteen years later, in the summer of 1938, two IRA veterans from the War of Independence, Seán Russell and Maurice Twomey, were sitting on the grounds of the Spa Hotel, New York, when the former reminisced about the damage O’Connor had helped inflict on the enemy homeland. Twomey was sceptical as to how useful this history lesson could be to them now but, to Russell, the late O’Connor had written the guidebook for his own bombing operation, to be undertaken in the following year.[29]

To be continued in: Out of the Ranks: Rory O’Connor and the Anglo-Irish Treaty, 1920-2 (Part III)

References

[1] Jackson, Valentine (BMH / WS 409), pp. 30-1

[2] O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013), pp. 95-6

[3] Ibid, p. 170

[4] Jackson, pp. 31-2

[5] Plunkett, Jack (BMH / WS 865), pp. 15-6

[6] Archer, Liam (BMH / WS 819), pp. 13-5

[7] Lynch, Michael (BMH / WS 511), pp. 160-2

[8] Kelly, Patrick J. (BMH / WS 781), pp. 50-3

[9] Knightly, Michael (BMH / WS 834), p. 13

[10] Evening Herald, 17/03/1919

[11] Ibid, 18/03/1919

[12] Ibid, 29/03/1919

[13] Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland, Volume 1 (Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008), pp. 188, 190

[14] Evening Herald, 29/03/1919

[15] Béaslaí, p. 199

[16] Ibid, p. 233

[17] Plunkett, pp. 43-5

[18] O’Donoghue, Patrick (BMH / WS 847), pp. 9-10

[19] Béaslaí, pp. 239-40

[20] Plunkett, pp. 32-4

[21] Archer, p. 18

[22] Traynor, Oscar (BMH / WS 340), pp. 49-51

[23] O’Leary, Michael (BMH / WS 797), pp. 43-6

[24] McMahon, Liam (BMH / WS274), 22

[25] O’Leary, pp. 46-7

[26] Irish Times, 29/11/1920

[27] O’Leary, p. 47

[28] O’Donoghue, p. 13

[29] MacEoin, Uiseann. Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), p. 397

Bibliography

Books

Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland, Volume I (Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008)

MacEoin, Uinseann. Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

Newspapers

Evening Herald

Irish Times

Bureau of Military History Statements

Archer, Liam, WS 819

Jackson, Valentine, WS 409

Kelly, Patrick, J., WS 781

Knightly, Michael, WS 834

Lynch, Michael, WS 511

McMahon, Liam, WS 274

O’Donoghue, Patrick, WS 847

O’Leary, Michael, WS 797

Plunkett, Jack, WS 865