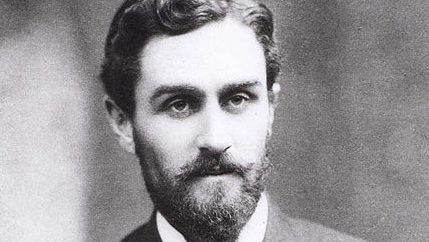

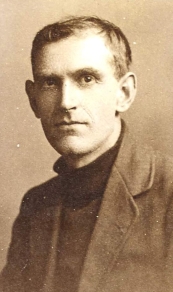

Tyrone accent, small brown eyes, regular nose, pale complexion, long face…has a habit of looking in a shifty way from side to side and downwards when speaking to anyone…keeps hands in trouser pockets; peculiar gait, takes long steps and looks shaky at the knees when walking.[1]

(Police description of Patrick McCartan, May 1916)

Choosing the Best Man

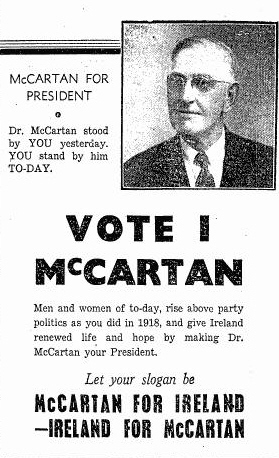

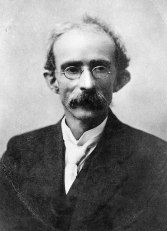

Politics makes for strange bedfellows, even for the Irish Times, but, so explained its editorial, a higher principle was at stake: should the Presidency of Éire be defined by party machinery or individual worth? While elections in Ireland were nothing new, the one in June 1945 for the head of the twenty-six county state was a first. Dr Douglas Hyde had secured that honour seven years by unanimous agreement of the nation’s elite; among his many achievements, Hyde belonged to no political camp and was thus an uncontroversial choice. But now the electorate had come to a three-pronged fork in the road, with a trio of candidates before them: two titans in Seán T. O’Kelly and Seán Mac Eoin, and a third hopeful, Dr Patrick McCartan.

That McCartan was running at all was a surprise, considering he had only just about secured the minimal number of signatures on his nomination papers, these being from TDs and senators in the Farmers Party. This was despite McCartan not standing on their platform, or for any faction for that matter, as opposed to the blocs – and powerful ones at that – behind the other two contenders: Fianna Fáil for O’Kelly and Fine Gael for Mac Eoin.[2]

That McCartan was running at all was a surprise, considering he had only just about secured the minimal number of signatures on his nomination papers, these being from TDs and senators in the Farmers Party. This was despite McCartan not standing on their platform, or for any faction for that matter, as opposed to the blocs – and powerful ones at that – behind the other two contenders: Fianna Fáil for O’Kelly and Fine Gael for Mac Eoin.[2]

Which made McCartan’s chances something of a long shot but, for some, his independent status was part of his appeal. “We are glad Dr McCartan has been nominated,” wrote the Irish Times:

We believe that he is a true patriot whose abiding interest is the welfare of the State. Undoubtedly his candidature will have a profound effect on the outcome of next week’s election. By his challenge to the two big parties he has shown himself to be a man of courage as well as of principle. He is fighting a lone battle; but we are convinced that he will not lack popular support.

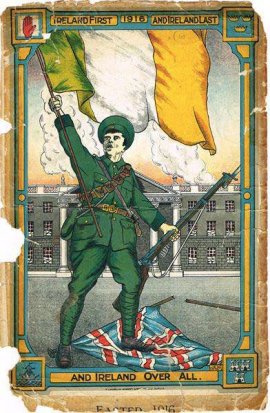

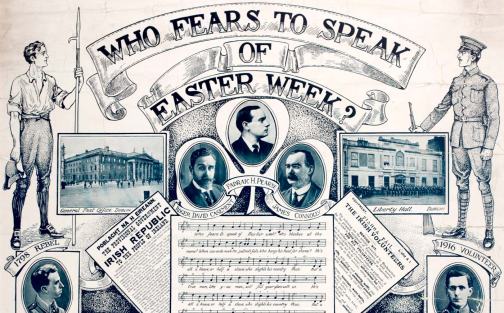

There were grounds for believing the last point: a straw poll conducted by the newspaper put its favourite’s support at 30.75%, not so far behind Mac Eoin’s 32.48%. The remaining 36.75% had O’Kelly at the fore but, if his lead was formidable, the gap did not appear insurmountable. While the other two had national records second to none – from O’Kelly playing “a man’s part in the Rising of 1916” to Mac Eoin’s time as “active guerrilla leader” during the War of Independence – McCartan’s own was “impeccable”, having been “throughout his life…closely associated with the Irish independence movement.”[3]

For readers scratching their heads at why a broadsheet of genteel respectability was cheerleading for such an unrepentant Fenian, the Irish Times admitted that “this newspaper hardly can be accused of active sympathy with his political ideals.”

Nonetheless:

We are convinced that, of the three candidates, he is the most suitable. We do not wish to disparage either of his rivals. They are both men who have done the State some service…The fact is, however, that they are both party politicians, for which reason we cannot support them…The electors’ duty is to choose the best man, and ignore all party ties.[4]

Whether the electorate did just that on the big day, the 16th June 1945, is a matter of debate. When the first preference votes were totalled, it was a resounding win for The Powers That Be:

Seán T. O’Kelly – 537,965

Seán Mac Eoin – 335,543

Patrick McCartan – 212,791

An overall majority had been denied to all three contenders, necessitating a sequel count based on the second preference votes, but it would be between O’Kelly and Mac Eoin, the underdog having been edged out. The Irish Times put on a brave face when O’Kelly was announced as the new President of Éire, taking solace in how the Fianna Fáil standard-bearer had not had an easy victory. That the Independent had earned support at all was seen as a win in itself.

Besides:

We feel that Dr McCartan, whose chances of success from the very beginning were slight, has done a national service by his courageous candidature, which, of course, has been financed out of his own pocket. He had proved that there is still a hard core of intelligent opinion in this country which is prepared to turn a deaf ear to the platform bellowings of the politicians.[5]

Which, again, is debatable. Either way, this sort of quixotic endeavour was characteristic of McCartan. He had been the dissenter in the system, an eternal maverick, even as far back as January 1916 when, at a meeting of the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), he had voiced doubt about the wisdom of rebellion without first securing popular support.[6]

The Supreme (Committee)

Though this caused a stir from a number of those present, Denis McCullough, as Chairman of the Supreme Council, was more understanding. Shushing the critics, to whom any chance of a fight against the British occupation must be seized and without delay, McCullough pointed out that the question was a fair one and the condition McCartan raised entirely in keeping with their Constitution.

On the other hand:

I stated that we had been organising and planning for years for the purpose of a protest in arms, when an opportunity occurred and if ever such an opportunity was to arrive, I didn’t think any better time would present itself in our day.

With both differing strands of thoughts – McCartan’s caution versus hard-line pugnaciousness – appeased, the subsequent discussion was conducted in a more judicious manner, ending in an agreement to carry out such a ‘protest in arms’ upon any of three contingencies:

- Any mass arrests of Irish Volunteers, particularly their officers.

- Conscription imposed on Ireland.

- The premature ending of the Great War, at least on Britain’s part.

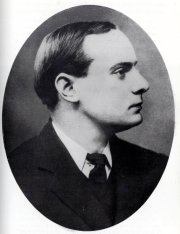

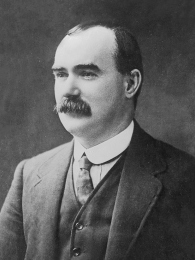

A compromise had been reached: commitments made without too much of a commitment. To take the IRB – as well as the Irish Volunteers which the Brotherhood had been infiltrating since their formation in November 1913 – into more of a war footing, a Military Committee was formed, consisting of Tom Clarke, Seán Mac Diarmada, Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt, Joseph Plunkett and, later, Thomas MacDonagh and James Connolly.

“I think that they were given limited powers of co-option,” McCullough wrote years afterwards, in 1953, to the Bureau of Military History (BMH). “However, I am not certain of these latter details about the Military Committee.”[7]

It says much that not even the President of the IRB’s ruling clique was entirely sure about the goings-on of one of its junior bodies. McCartan provided more details in his own reminiscences about the aforementioned gathering, such as Clontarf Town Hall as its location. He also recalled himself saying: “We don’t want any more glorious failures,” which was what presumably provoked the hullabaloo that McCullough described and was enough for one other attendee, Diarmuid Lynch, to later write of McCartan as being against the whole idea of an uprising.

Glorious Failures

“This was not true,” McCartan clarified to readers of his own BMH Statement. It was just “I did not want our people to rush out into a revolution unprepared and without practical hope of success” and was unafraid to say so, even to a roomful of his peers. Not that the others on the IRB Supreme Council had anything stronger to contribute:

I remember Pearse saying in a vague sort of way, “Around Easter would be a good time of the year to start a revolution”. Pearse spoke more like as if he was thinking aloud when he said this, rather than making a definite proposal.

McCartan did concede the possibility that he was misremembering things – such are the perils of recording decades after the event. He was sure, however, that no definite date for insurrection was set at the meeting – he had been there, after all – nor had it been beforehand. Otherwise, “I’m certain Tom Clarke would not have concealed such important news from Denis McCullough and myself.”[8]

Time had perhaps allowed him to make a generous appraisal. In the immediate aftermath of the 1916 Rising, however, McCartan may have been of a very different certainty. By mid-1917, he was in New York, on behalf of the underground Irish government, where he met two other revolutionary expatriates, Frank Robbins and Liam Mellows. Easter Week had marked all three, albeit in different ways: Robbins had fought in Dublin as part of the Irish Citizen Army, while Mellows commanded the Irish Volunteers in Co. Galway.

Mellows was supposed to have been McCartan’s superior officer, had McCartan led the Tyrone Volunteers to him as intended, but obviously very little had gone as planned and it was left for the trio to make the best of things with each other in a foreign land. Mellows and McCartan quickly grew close, much to Robbins’ chagrin, for, while he and Mellows were walking together, Robbins asked the other man why he was in a gloomy mood.

“If I had known as much in Easter Week as I know today, I would never have fired a shot,” Mellows replied. The authority of the IRB Supreme Council had been usurped, Mellows explained, and its prerogative stolen by the Military Committee in order to launch the Rising under false pretences. Mellows went so far as to call the Committee a junta, an opinion Robbins suspected was more McCartan’s than Mellows’ own. Though Mellows hotly denied this was the case, an unconvinced Robbins insisted on setting straight the record as he saw it: the men of the Military Committee such as Clarke, Pearse and Connolly were heroes who had laid down their lives for Ireland, however much McCartan badmouthed them to justify his own dereliction of duty.

Mellows was thankful when Robbins was done, saying he had helped set his mind at ease. Robbins was troubled all the same; McCartan had been in the United States for less than a fortnight and already he was raising awkward questions about the rights and wrongs of Easter Week.[9]

Making Sense of Things

Making Sense of Things

(From Patrick McCartan’s interview with the Pension Advisory Committee on 28th July 1940)

Q: Were you in touch with them here in Dublin at that time – the three weeks before Easter Week [1916]?

A: I could not tell you. I was up in Dublin sometime or other and saw Tom Clarke. He told me to see Pearse. I saw Pearse, and Pearse told me that our function would be to go to a place called Belcoo [Co. Fermanagh]. That there was a plan – there was to be a German landing. If there was a German landing, we were to go to Belcoo and join up with Mellows in Galway. He did not say Mellows. I had to keep the line of the Shannon. He said there might be other instructions later. He did not give me the instructions in case of no German landing and that puzzled us. The idea of that I could not tell you.

Q: For the three weeks before Easter Week, were you doing anything particular?

A: Not that I know of. I came up on Holy Thursday [the 20th April 1916]. I got word on Holy Thursday and I came up to make sure – I think it was Burke, now Dr Burke. I came up on Holy Thursday and saw Tom Clarke. He was enthusiastic about it and he expected a German landing. Going home on the train [to Co. Tyrone], I saw in the evening paper where the Aud was captured and Saturday I sent up my sister and two Miss Owens to make sure: one of them came back on Saturday night and had seen Tom Clarke and he said it was hopeless but we must go on. On Sunday, the other two arrived back with [Eoin] MacNeill’s message [cancelling plans for the Rising]. The Belfast men came down to Tyrone. I did not know they were coming until they arrived.

Q: That was on Sunday [the 23rd April]?

A: Saturday or Sunday. We sent them back on Sunday after getting MacNeill’s message.

Q: It was Friday, probably, you were coming home?

A: Friday, I think it was.

Q: On Saturday, you sent your sister and the Misses Owens to Dublin and they returned?

A: One of them returned on Saturday night by the mail train and the other two on about 2 o’clock on Sunday.

Q: And the Belfast men came on Saturday night?

A: Yes.

Q: On Sunday of Easter Week, the Belfast men went back?

A: Yes.

Q: You remained at home that day?

A: I suppose I went back and pretended to be as innocent as I could.

Q: During Easter Week?

A: Monday, I got word from Pearse. The message was “We started. Carry out your orders”. Matt Kavanagh’s brother brought it to me. That was about dark on Monday evening and I sent word around that we were going to Clogher and got Fr. O’Daly out of his bed at 4 o’clock in the morning. On Tuesday, we had all the fellows mobilised and then our orders were to go to Belcoo. We did not know what we were going to do. That night, Fr. O’Daly and Fr. McNeillus came and then that night I spent telling the rest to go home. We did not know what to do.

Q: Wednesday, Thursday and Friday?

A: Wednesday, I don’t know what I was doing.

Q: For the rest of the week, were you a sort of standing to?

A: Our idea was to start out again as soon as we would get out [sic] bearings and see what we could do. I did not go back to work after that at all. Where I was or what I was doing, I don’t know. Fr. Daly and Father Coyle and myself [and] Fr. McNeillus, we were meeting and discussing business.

Q: For the rest of the week you were waiting then?

A: After Thursday, they began searching every house. I just escaped out of my father’s house that day.[10]

Dealing with the North

If Ulster does not loom large in the memory of the Rising, then, in fairness, it was never intended to be more than an afterthought. This was made plain to McCullough when summoned to a meeting with Pearse and Connolly in Dublin. Despite his presidency of the IRB Supreme Council, as well as rank of commandant over the Belfast Volunteers, McCullough listened passively as Pearse laid out the plan of action.

Once the Rising was decided on, McCullough would receive a coded message a week beforehand. Come zero hour and he was to mobilise his subordinates, armed and equipped accordingly, and march them all the way to Tyrone, join up with the Volunteers there, and then continue towards Galway, where Mellows was to take overall charge. All of which was quite an undertaking, considering how this was to be done on foot, to say nothing of the limited armaments of the Belfast men, for surely the various barracks and garrisons of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) along the way would resist.

When McCullough pointed this out:

Connolly got quite cross at this suggestion and almost shouted to me “You will fire no shot in Ulster: you will proceed with all possible speed to join Mellows in Connaught, “and”, he added, “if we win through, we will then deal with Ulster”…I looked at Pearse, to ascertain if he agreed with this and he nodded assent, with some remark like “Yes, that’s an order”. That interview is perfectly clear in my mind, and was exactly as I set it down.[11]

McCartan was given similar instructions by Pearse, who told him, in response to the question of any RIC strongholds facing them: “Don’t waste time dealing with police” – which did not in itself make the problem go away. McCartan at least had the promise of German reinforcements – which McCullough did not, if his memory was as clear as he claimed – as relayed to him by Clarke while staying the night in the latter’s house. McCartan had received word in Tyrone on the morning of Holy Thursday, the 20th April 1916, about a shipment of arms the Aud was bringing for the rebellion, but details were so vague that he went down to Dublin to have them clarified.

There was nothing to worry about, Clarke assured him, not with five thousand – at least! – of the Kaiser’s finest on their way. By the time McCartan left for the Friday morning train back to Tyrone, he was as giddy as Clarke – until, that is, he read of the arrest of Roger Casement and the Aud’s capture while sitting in the carriage with his newspaper. While he did not think these twin blows would be enough to derail their enterprise, the mood in the North was apprehensive enough already, even amongst Those In The Know. While passing through Monaghan on the way to see Clarke, McCartan was warned by a priest, Father McPhillips: “Tell them in Dublin not to do anything until the British try to enforce conscription and then the whole country will be behind you.”[12]

Another man of the cloth, Father Eugene Coyle, had attended a gathering of Volunteer officers a day or two earlier, on the Tuesday or Wednesday of Holy Week, in Beragh, Co. Tyrone. McCartan and McCullough were present, along with another Fenian-minded priest, Father O’Daly, and several other insiders. Though Father Coyle was to describe it as a ‘council of war’, the mood was far from belligerent, particularly when the latest missive from Pearse, outlining the joint role of the Tyrone and Belfast contingents, was read out.

If McCullough had been apprehensive upon hearing it the first time, then the others were no less dismayed: the distance to cover was formidable, their men undersupplied and the countryside they were to enter strongly held by the enemy. When one of the attendees, failing to read the room, suggested they begin by blowing up trains carrying British soldiers from Derry to Dublin, the threat to civilian life was deemed too great by the rest. The proposal was quickly dropped.[13]

Effective Organisation

The presence of Fathers Coyle and O’Daly would not have surprised the RIC District Inspector (DI). When writing his report in May 1916 about the disturbances in Tyrone of the month before, DI Conlin noted how “Dr Patrick McCartan, a dangerous IRB suspect” had a way of attracting “considerable clerical support, because he was very astute and had the art of hiding his real sentiments from those to whom he did not wish to reveal them.”[14]

No dissembling would have been necessary with Father Coyle, who had been converted to physical force methods even prior to knowing McCartan. Alarmed at the rise of the Ulster Volunteer Force in his parish of Fintona, Co. Tyrone, Coyle decided it was only just that his congregation should likewise exercise their right to bear arms. Paying for fifty rifles from his own means, which he distributed to the Fintona Volunteer Company, brought him to the attention of McCartan, then the medical officer of the Gorteen Dispensary District.

“Dr McCartan and I became great friends,” Father Coyle told the BMH. “I had great admiration for the work he was doing in organising the Volunteers and the IRB all over the north of Ireland.”

The respect went both ways, with McCartan allowing his priestly friend to sit in on IRB conclaves, where he also made the acquaintance of McCullough and Father O’Daly. Coyle’s religious scruples held him off from taking the Fenian oath – secret societies being frowned upon by the Church – though not from accompanying McCartan in the latter’s car to Dublin and driving back with guns purchased out of McCartan’s medical salary. Father Coyle’s martial philosophy was more reactive than proactive – “I believed that defensive military preparation by our people was the keystone of our national wellbeing,” as he put it – while his friend’s was willing to risk an outright insurrection – when the time was right, that is.

In McCartan’s view, the time was most certainly not right, so he told Father Coyle sometime in early 1916. He was not alone in thinking so, as he relayed to his priestly confidant about an IRB summit in Dublin from which he had just returned:

A small minority of the delegates expressed the opinion that the Rising should be postponed until the country was better organised, as in many counties there did not exist any organisation whatever…The position in the north then was that in all areas except East and South Tyrone and Belfast City there was no organisation. In the south, with the exception of Dublin, Galway South and Wexford, there was little evidence of any effective organisation.

Nonetheless, the Rising was set to go ahead, much to McCartan’s frustration. His IRB co-conspirators could not seem to think in terms outside of Dublin’s, he complained. If it was fine for the big city, it was the same for everywhere else, went the attitude.[15]

Both he and Father Coyle knew better. When McCartan was singled out for his alleged culpability in the subsequent debacle, Coyle hastened to set the record straight or at least place it in context. “Why specially condemn him for inactivity when in areas like Cork and Kerry with friendly populations, with better organisation, more men, more arms and better equipment, no action took place,” he asked, defending the honour both of his friend and the North’s.[16]

Contradictory Conflictions

Contradictory Conflictions

And yet, perhaps there is more than a hint of hindsight in such remarks, composed decades afterwards when the Rising might have appeared doomed from the start. Other sources, written mere weeks after the venture, present McCartan in a much more confident, even cocksure light. A letter of his in early June described how he had, on the Easter Tuesday of the 25th April, proposed to a RIC sergeant that he and his colleagues:

…would get their jobs under the new government if they did not actively oppose us. And I advised him to pretend to do his duty but not be too officious and to pass the word to those whom he could.

McCartan obviously was envisioning himself as someone with a say in this new state of affairs. The sergeant instead reported this seditious offer to his superiors, leaving McCartan open to charges under the Defence of the Realm Act and with no choice but to go into hiding:

Of course I was an ass for saying anything to him but at the time I was certain we would have a walk-over as I thought the Germans were here.

Evidently, news of the Aud’s capture had not deterred McCartan from believing in the story Clarke had spun for him about overseas reinforcements. While he knew all too well now that this had been a forlorn hope, at the time: “I thought the hour for discretion had passed.”[17]

This was not necessarily post factum bravado on McCartan’s part. The RIC report of DI Conlin, written on the 23rd May 1916 to explain to his employers in Dublin Castle how Tyrone had fared, made a point of identifying McCartan as “not only a local leader in the rebellion movement but…was a leader in the higher councils of the Dublin rebels.” Such as the trust bestowed in him that “he had control of large funds from America for propaganda work…I have evidence of large payments made by him to such men as T.C. Clarke of Dublin, who has since been shot, and to Professor MacNeill and others connected with the Sinn Fein movement.”[18]

And McCartan led not just from the shadows. Although the authorities had him under enough surveillance to record his visit to Dublin on Good Friday, as well as observing him and several others in Tyrone “making final preparations for the rising,” Conlin mistakenly believed Easter Wednesday, the 26th April, to be the set date for action. Even when news reached the RIC in Omagh of the fighting in the capital, the warning was considered insufficiently clear for the police to do much more than stand by. Conlin seemed unaware of the divisions within the rebel leadership, and the contradictory orders about whether or not the Rising was to go ahead, attributing instead its failure in Tyrone to the “special zeal, energy, tact and wholehearted devotion to duty” of the RIC.

Self-congratulation aside, the District Inspector was correct in his report that the majority of Tyrone Volunteers simply decided to sit things out:

When the Sinn Feiners assembled at Eskerboy on night of 26 ult. they numbered only 105 all told. The question of attacking the police barracks at Carrickmore was put to a vote, and there was a majority of 3 or 4 against the attack because the forces were not sufficiently strong.

However:

Dr McCartan and the more violent of his supporters fought hard to lead the attack. He failed to carry his point but he had not yet given up hope of raising the republican flag in Tyrone, and he expressed himself to that effect and promised that a sufficiently large force would be in readiness in a day or two.

McCartan never got the chance. On the next day, continued Conlin, three hundred British soldiers drove into Carrickmore and aided the RIC in raiding:

…the home of Dr McCartan’s father where the meeting had been held the previous night, and seized several thousand rounds of ammunition and 15 or 20 automatic revolvers and cartridges and other equipment. This military demonstration and the seizure of the ammunition put the finishing touches on the rebellion in Tyrone.[19]

That McCartan was able to take his two revolvers with him, while fleeing his father’s house in Eskerboy just in time to avoid arrest, was a small victory, though it did little to mitigate the loss of the rest of the arsenal. The Tyrone Volunteers had been in two minds about rebellion, or at least about putting the principal into practice, but now the choice had been made for them, and there was nothing else to be done except lie low and hope the military and police parties would pass them by.[20]

If the Volunteers had really been debating the merits of attacking Carrickmore RIC Barracks, then this meant a departure from Pearse’s instructions to do nothing against the police in Tyrone. As Seán Corr remembered it, however, the question had been no more ambitious than whether to seize explosives from Carrickmore quarry, which ended in the decision not to. Other insider accounts give the impression of an army that had already lost its spirit, going through the motions while waiting for it all to end one way or another.[21]

“When I met [McCartan on Monday evening] he seemed to have had a bad time and showed the effects of it,” recalled Jim Tomney. Tyrone had by then suffered its sole casualty of Easter Week: McCartan’s car, left a burning wreck after soldiers paid a call to his house. With the promise of worse to come, now that the authorities were on the alert, a shaken McCartan told Tomney “that he was not in favour of doing anything further.”[22]

Flight or Fight

(From Patrick McCartan’s interview with the Pension Advisory Committee on 28th July 1940 – continued)

Q: You went on the run?

A: I was on the run from that on [until] about February or January of 1917. It was the end of January because I was arrested on the 28th February.

Q: The 21st or the 22nd February?

A: Sometime like that.

Q: You were deported then?

A: I was in Oxford and Fairford, and we came back for Joe McGuinness’ election.

Q: You escaped from there in May 1917?

A: Yes.

Q: You assisted at the election?

A: Yes.

Q: It was at that time that you were ordered to go by the Provisional Government?

A: We called it a Provisional Government. It was really the Supreme Council of the IRB.

Q: You could not get a boat to Russia – you were ordered to go to the USA and make your contact there?

A: That is right.

Q: About what time did you leave for there? In June?

A: Yes. The prisoners got out of Lewis [sic] Jail about June. Three weeks before that. It was after McGuinness’ election. I went to London and gave a statement to the Russian – to a secret agent. Then I went to Liverpool looking for a boat and there I saw about the prisoners getting out and crossed over in the boat with them here. I got a statement signed by the officers which was presented to President Wilson.

Q: De Valera signed the statement?

A: Yes and MacNeill and all the officers.

Q: In addition to the Supreme Council of the IRB, you had now the sanction of all the released prisoners?

A: Yes, all the released prisoners really.

Q: With that statement, you left?

A: Yes. I sailed on the Baltic as a seaman. I forgot the exact date. Whatever date they got out, it was on the following Wednesday.

Q: You went to America?

A: Yes.[23]

Coming to America

For Frank Robbins, McCartan’s arrival in New York was the start of one headache after another. He and Mellows made the acquaintance of the newest entrant in the Gaelic American newspaper offices, the base of operations of John Devoy, the hoary old Fenian legend. McCartan had only just stepped foot on American soil and already he was at the centre of a crisis.

He had brought with him a document, stating the case of Irish freedom, and addressed to President Woodrow Wilson and the United States Congress. The twenty-six signatures at the end, all of which belonged to Volunteer officers who were newly released from prison, made this as official a statement as could be made by the independence movement. Elaborate preparations had gone into its making: written in indelible ink on starched linen, which had then been washed into a state pliable enough to be sewn onto the inside of McCartan’s waistcoat.

There was just one problem, as McCartan revealed to the others in the room: he had left his waistcoat, and the document within, on the ship.

Whether this was something important or not, McCartan could not seem to decide, at least in front of Devoy, Mellows and Robbins. Fed up with the dithering, Robbins finally undertook to retrieve the document himself. Knowing McCartan had spent his Atlantic crossing on the forecastle of the Baltic ocean liner, Robbins would sneak on board, find the rogue item of clothing and bring it and the contents back. McCartan appeared relieved at hearing this and followed Robbins and Mellows to the harbour of the West Side, where the Baltic was docked. Robbins left the other two on a street corner and, assuming the confident air of a man who had every right to be where he was, tried walking past the guard-sheds of the dock.

Unfortunately, the watchman on duty was not so trusting as to let Robbins pass without a challenge. Nor was he swayed by Robbin’s sob-story of being a down-on-his-luck sailor who had missed his previous ship and was desperate to find employment on another. No pass, no entry, the sentry insisted, forcing Robbins to return, defeated, to where Mellows and McCartan were waiting.

Though the story was to have a happy resolution, Robbins found the whole thing more than a little frustrating:

I do not know how the document was brought ashore eventually but there is a point of view held that it was through the influence of Clann na Gael [the Irish-American organisation headed by Devoy] that this problem was overcome. Dr McCartan in his book “With De Valera in America” says he took it ashore with him on the Sunday, the day the ship docked. Yet on Monday he was deploring its loss, and was party to, and in agreement with my effort to get it by boarding the ship. However, I have given the facts as known to me.[24]

“Frank, McCartan will never make a revolutionist,” Devoy told Robbins one day. “He can never make up his mind about anything which is very important, and I attribute this to being an inveterate smoker.”[25]

Regardless of suspect tobacco habits, Robbins was stuck with McCartan for the meantime. Devoy put his own doubts aside to add the newcomer to the circuit of speakers in talks organised by Clan na Gael, in which McCartan performed to packed houses, sharing the stage with other activists such as Mellows, Sidney Czira (née Gifford) and Hannah Sheehy-Skellington, while Robbins sang suitably rousing songs like Call of Erin, Wrap the Green Flag Round Me and Armed for the Battle.[26]

But patriotic productions were only part of the agenda for McCartan and his stateside peers. Whatever its faults as a military operation, the 1916 Rising had at least set the Irish revolution in motion, and McCartan, whatever his private views about the Easter Week of the year before, was eager to play his part. When Czira told him that a German friend of hers, Lucie Haslau, had bade farewell to some of her compatriots from the German Embassy who were homebound, given the state of war that now existed between their country and America, McCartan was surprised – and intrigued.

But patriotic productions were only part of the agenda for McCartan and his stateside peers. Whatever its faults as a military operation, the 1916 Rising had at least set the Irish revolution in motion, and McCartan, whatever his private views about the Easter Week of the year before, was eager to play his part. When Czira told him that a German friend of hers, Lucie Haslau, had bade farewell to some of her compatriots from the German Embassy who were homebound, given the state of war that now existed between their country and America, McCartan was surprised – and intrigued.

What routes were they using, he wanted to know. McCartan returned to Czira’s flat in Beekman Place, New York, the next morning, at a notably early hour. Mellows was with him, the two men being eager to learn if they could take the same ships as the departing diplomatic staff for business of their own in Germany.[27]

Caught in the Act

(From Patrick McCartan’s interview with the Pension Advisory Committee on 28th July 1940 – continued)

Q: When were you arrested in Canada?

A: That was in October 1917. The same year.

Q: You spent ten weeks in jail there?

A: Yes.

Q: You were arrested there attempting to go to Germany for special explosives?

A: That is right.

Q: At that time, you were working specially for this group of officers?

A: I don’t know who was in charge then but the question was whether these could be used or not. First, I was to go to Liverpool to organise for the use of them and then it was decided for two to go to Germany. Mellows and I were to go. Mellows was to go first and I was to stay behind representing and then it was necessary to make a second trip.

Q: You were working at any rate for some GHQ and you were working still on the instructions received from [Éamon] de Valera and the others officers there?

A: That is right.

Q: Did you return then to New York after that?

A: They sent me back to New York for trial. I went on a seaman’s passport under an assumed name.

Q: How long were you held?

A: They kept me in the Custom House in the Secret Service place for a couple of days.

Q: You were released then?

A: I was brought into court and got out on bail, first trial.[28]

Our Gallant Allies in Europe

An American-German-Irish alliance had long been identified as the ideal leverage by both revolutionaries and their opponents. While discussing the history of resistance to British rule in Tyone, dating all the way back to the O’Neills in the 16th century, DI Conlin, noted, in his report of May 1916, how:

…this appealed to the sentiment of extremists amongst the Irish in America, and brought unlimited funds through the Clan na Gael, which have doubtless been augmented since the outbreak of war by subscriptions from German-Americans to foster rebellion in Tyrone.[29]

And at the centre of this Transatlantic-Continental conspiracy was, of course, McCartan:

…delegated to Tyrone, his native county by the American Clan na Gael to spread the Sinn Fein and revolutionary movement. His private papers, bank accounts, etc., which I have seized, prove this conclusively.[30]

Even after the absence of their ‘gallant allies’ when it mattered on Easter Week, McCartan stayed true to his Teutonophilia. “Hurrah! Hurrah!! Hurr-ah!!! Great news in yesterday’s papers!” he wrote excitedly, on the 4th June 1916, about the naval news on the Battle of Jutland. “Brittania who rules the waves admits the loss of fourteen warships and others missing. Our cause is not therefore hopeless.” It was time, thus, to renew strategic ties: “We want a representative in Berlin to take [Roger] Casement’s place, and he should get there quickly.”

In the event of no takers, he offered himself for this diplomatic role:

…for I am convinced it is the proper thing to do. If an Irishman arrived there, “to put conditions in Ireland before the German Government” and publish the fact, it would serve both Germany and Ireland. Even though it were impossible for an expedition to come here it would frighten John Bull into giving better terms to Ireland in the coming or promised reform. It would also keep up, or help at least to keep, the enthusiasm of the Irish in America for Germany and perhaps influence the presidential election and Wilson. If the expedition came here it would prepare the mind of the people for it and give them heart.[31]

In other words: whatever happened, an envoy in Berlin could only benefit their cause. Almost a year later, McCartan saw the opportunity to put his theory to the test. Czira answered his request by putting him and Mellows in touch with Frau Haslau and allowed the budding cell the use of her flat for meetings, though she kept her own involvement to a minimum, save counsel. When Haslau asked if she could include a fellow worker in German propaganda, a Dr von Recklinghausen, Czira advised her and Mellows against this, fearing the doctor was too high-profile.

Nonetheless, she did not forbid it and her warning went unheeded, as did her urging of McCartan not to tell Devoy what they were doing. She regarded the Clan na Gael head as a petty tyrant, while Devoy resented the Young Turks who were bucking his authority. McCartan attempted to straddle both horses, continuing to associate with Czira and her allies, while arguing to them that it was unfair to leave the ‘Old Man’ in the dark.[32]

Besides, Devoy had German contacts of his own, exchanging word via a cablegram between Europe and New York, and was sufficiently informed to host a gathering in the Astoria Hotel with McCartan, Mellows and Donal O’Hannigan, the commander of the Louth Volunteers during Easter Week. Devoy assigned to the others their destinations: O’Hannigan was to return to Ireland and await contact with German operatives, with McCartan and Mellows making their way to Germany.

Everything seemed to be laid out smoothly – except for how, as McCartan, Mellows and O’Hannigan left the Astoria, they were tailed by four strangers who O’Hannigan assumed to be police detectives. Though the trio were able to give their shadowy escorts the slip, it was clear that they had not been as discreet as they should, McCartan especially.[33]

As if Dr von Recklinghausen was not inconspicuous enough, McCartan was warned by Devoy not to be paying calls to a certain German woman – Haslau, presumably – who was already known to the American authorities. McCartan continued doing so anyway. Another blunder was when he and Mellows were at the New York Shipping Board for their seamen’s papers in preparation for their Atlantic crossing. As befitting men on a secret mission, both gave false names and provided forged birth certificates as ‘proof’ but, when McCartan was asked by the official at the desk to name his previous ship of employment, he answered incorrectly, as he did immediately after about whether he had been a sailor or foreman before. Though the official made no comment, anyone checking McCartan’s statements against the Board books could tell that something was amiss.

While McCartan was able to secure the necessary paperwork, according to Robbins:

Mellows also informed me that McCartan, who was employed as a cook, was ordered to report daily at 7 am to the ship while she was in port in New York. This he failed to do, on many occasions turning up as late as ten o’clock.[34]

Between this and that, it is little wonder , when the time to move finally came, that their mission was halted in its tracks, like Easter Week all over again. McCartan had set off in October 1917, stopping off in Halifax, Canada, where he was detained by the authorities. A week later, Mellows too was arrested, still in New York, with his fraudulent seaman’s passport on him. Neither would be leaving American shores quite yet, though McCartan at least had the distinction publicly bestowed on him by the media as the “First Ambassador to the Irish Republic.”[35]

Envoy Work

(From Patrick McCartan’s interview with the Pension Advisory Committee on 28th July 1940 – continued)

Q: During ’18, you were still there in America?

A: Yes, I was still there.

Q: Were you acting as an envoy there?

A: Yes. That was the best period of work I had, because de Valera came in 1919 and Harry Boland, of course, they took the…

Q: Were you officially working there as envoy right up to the time they came?

A: Yes. I gave statements to the State Department, all that kind of thing. The 1918 Election was here, I sent a note to the Legation in Washington [that] Ireland was separated from the British Empire.

Q: That would be after they proclaimed the Republican Government here in 1918?

A: I did not wait for the Proclamation. As soon as the result of the Election [came in], I acted.

Q: You had been acting as envoy prior to that?

A: Yes.

Q: Full time?

A: Yes. I delivered a statement up to [President Woodrow] Wilson or his secretary any time I got one. Then we protested about the Conscription of Irish Nationalists also, and the Conscription here in Ireland, [we] sent it to the State Department.

Q: Before de Valera came over, were you officially appointed by the Republican Government at that time?

A: When Harry Boland came, he gave me the official note appointing me by de Valera as head of the elected Government – he called it, he signed it – of Ireland.

Q: From that on, you were acting in that capacity?

A: Until I went to Russia in 1920. December 29th, 1920, I think, I sailed for Gottenburg.

Q: Who sent you to Russia?

A: De Valera. He gave me one of those printed documents with instructions. It was in Irish and French.

Q: You arrived there?

A: 14th February [1921].

Q: You returned to Ireland what time?

A: I left Moscow, February, March, April, May, June, 14th June ‘21. I was exactly there four months. Then, I think, I spent about a month or so in Berlin, as John T. Ryan.

Q: You were full time there?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you return here?

A: I returned here then during the Truce, I could not give you the exact date, I have not the old passport.

Q: You were there up to the time of the Truce?

A: I was. As a matter of fact, the Truce took place when I was in Germany.[36]

Eastern Promises

Russia had been McCartan’s original intended destination, back in mid-1917. After his arrest and a spell of deportation in England, he had returned to Ireland, participating in whatever opportunities came his way such as canvassing in the South Longford by-election, but otherwise at a loss of what to do. In the wake of Easter Week, the IRB Supreme Council had been reformed without him, though it is unclear if this was an act of exclusion or his own decision.

If the former, then debarment did not stop the Secretary of the Supreme Council, Seamus O’Doherty, from sharing news with him or asking for advice; if the latter, McCartan still itched to contribute to the cause. The O’Doherty family house in Dublin provided a venue for him and like-minded souls to drop in and chat about the state of affairs, and it was during one of these symposiums, between McCartan, O’Doherty and Kevin O’Shiel – another Tyrone-born activist – that the notion of sending an emissary to the Soviet Union on behalf of the Irish Republic was born. O’Doherty forwarded this suggestion at the next Supreme Council conclave, which confirmed it, at least according to McCartan’s account, which makes it all sound very much an ad hoc process, as was the subsequent change of plans to send McCartan to America instead, based on how catching a boat there seemed easier.[37]

Such extemporaneous spirit continued when McCartan finally made contact with the Soviet Union, through the Russian Mission in the city of Reval (modern day Tallinn), Estonia, which he reached on the 6th February 1921. He had hoped to mitigate the worst of this impromptu as far back as May 1920, when the idea of a Soviet outreach was next mooted. “As far as I am personally concerned I’ll go only on condition that I get plenary powers and that I shall have absolute authority no matter who is sent to make final decision in case of disagreement,” he wrote from New York. “This may seem at first sight an extraordinary demand but it is the only satisfactory course.”

Otherwise, standing as a warning was the historical example of Benjamin Franklin during his ambassadorial tenure in Paris – who “had no end of wrangles with his colleagues and in the end had to take the bull by the horns and act as his own judgement dictated” – and, more recently and closer to home, Roger Casement, whose lack of full authority “left him to an extent powerless and even suspected.” McCartan had no intention of letting history repeat itself where he was concerned – but, when the time came, history appeared to have had the last laugh.[38]

Upon meeting Maxim Litvinoff in the Russian Mission in Reval, on the 9th February, his Russian counterpart:

He seemed at first to study me as a sort of curiosity and asked me if I had any programme or plan to submit. As the Cabinet, so far as I know, never sent any recommendations nor suggestions after the receipt of the proposed Treaty and as President De Valera did not give me any specific instructions I was evasive and said that it was considered better to discuss proposals with them as we could only be expected to view the situation largely from an Irish point of view but we desired that whatever agreement, if any, we might make would be to our mutual advantage.

Unfortunately, Litvinoff saw through this prevarication: “He openly expressed disappointment and intimated that it was folly for me to proceed if I had no plan to submit.” At least Litvinoff was willing to discuss the situation with McCartan, specifically whether the Soviet Union would recognise the Irish Republic. The chief sticking point was the treaty being negotiated with Britain, which would react poorly to a separate deal with a country it considered part of its domain. Still, McCartan suspected Litvinoff was not completely averse to tweaking the lion’s tale; when he asked the Russian if he trusted Britain, Litvinoff answered with a sardonic laugh.

Despite the earlier brusqueness, the meeting ended on a positive note: McCartan could proceed to Moscow and meet Santeri Nuratova, Assistant Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.[39]

Mission to Moscow

Arriving in Moscow on the 14th February, McCartan made a point of being at the Foreign Office exactly on time. He did not have long to wait before his interview with Nuratova, who repeated Litvinoff’s line that the Anglo-Russian treaty-in-the-making was the hurdle to an Irish-Russian one, and the Soviet Union wanted the former very keenly, certainly more than the latter. When McCartan speculated on the chances of these talks with Britain falling through, Nuratova set him straight: “I may tell you confidentially they will not break down for we want the agreement. It is essential for us.”

The Irishman was again left in suspense as Nuratova said he would have to wait until the next day to learn if he could meet the next rung on the Soviet Foreign Affairs ladder: Georgy Tchitcherin, Secretary of State. When McCartan received the affirmative by a telephone-call to his hotel, he was once again punctual for the appointment. Tchitcherin was not, being delayed – so McCartan was told – by a few minutes. Which was not an auspicious start, nor was the opening awkwardness and confusion when the two men met:

Mr. Tchecherin appeared an extremely gentle sort of man, very polite and a trifle nervous. Both of us seemed embarrassed as to how to start. He mumbled rather than asked whom and what I represented. I submitted my credentials from President de Valera and he seemed to read and re-read them.

They were dated Dublin December 15. He asked if I came from Dublin and then asked how I came from New York while the credentials were signed in Dublin. He wanted to know if our Government were in New York. I explained all this. Then he suddenly asked me what I wanted and I said recognition by the Soviet Government and a discussion of co-operation which might be of advantage to both.

When Tchecherin queried Ireland’s sovereignty, considering how the country was still occupied by its neighbour, McCartan had his responses ready: did George Washington not lack full control of the American Colonies when receiving recognition from France against the same enemy as now? Had the Allies not acknowledged in Paris an independent government for Bohemia while it lay under the Austrian thumb? No other government admitted the Soviet Union as one of its own, even though it was accepted as a fact by the peoples of the world. Ireland, likewise, was denied official approval, even while the government McCartan represented ruled Ireland more truly than the British military did.

This question of recognition led to another: Tchecherin had read in the papers about the possibility of President de Valera accepting something less than a Republic, like Dominion Home Rule. Was this true?

Not at all, assured McCartan:

If we said we would accept Dominion Home Rule we would give away our whole case for nothing. Surely he could himself see that it would be very poor statesmanship for President de Valera to say he would accept Dominion Home Rule. There was one real danger of a compromise but it was one with which we were not likely to be confronted. If the British Government threw a genuine measure of Dominion Home Rule at us and virtually said ‘take it or leave it’ we might be compelled to operate it as many of our people might consider it more than they had ever hoped for in their lifetime. In such a case we would have to accept it or run the risk of splitting the people again into fractions.

But, as McCartan had said and what he stressed, this sort of make-or-break offer was very unlikely to happen. As the interview drew to a close, Tchecherin asked what was the likeliest outcome to expect.

“An Irish Republic or a land in ashes,” McCartan replied, “for it is going to be a fight to a finish.”[40]

A Fight to the Finish or Finishing the Fight?

There is no reason to think McCartan did not mean those words; indeed, one handshake made under the table – which did not reach the official memorandum – was for the Soviet Union to smuggle 50,000 rifles to Ireland. McCartan and Harry Boland were to handle the logistics, with the help of their Irish-American contacts and the Irish Overseas Shipping and Trading Company acting in Dublin as the front for surreptitious imports. As with other similarly grand guns-running plans during the War of Independence, this one fell through when the American authorities caught wind of it at their end and alerted their British counterparts. At least McCartan left Russia with his public mission a success, as an accord had been struck that made the Irish Republic the first nation to recognise the Communist state.[41]

Which was ironic, considering how its ideology would be as welcome as the Bubonic Plague in a staunchly Catholic Ireland – but one thing at a time. The possibility that McCartan had assured Tchecherin was impossible – that Britain would offer Ireland something less than a Republic – had just become a reality with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. McCartan returned to Dublin to attend the Dáil debates as the TD of the Leix-Offaly constituency, a seat he had won uncontested seven months ago in the General Election of May 1921. Such was Sinn Féin’s dominance that its candidates had not even needed to be in the country. But now this sort of absentee representation was no longer permissible. It was time to stand in the Dáil and be literally counted – for the Treaty or not?

Where McCartan stood on that question was one Dan MacCarthy dearly wished to have answered. As Whip for his faction, it was McCarthy’s duty to rally the other pro-Treaty TDs; a stressful job, as evidenced by how intent he seemed, during one parliamentary session, at poking holes in his cushioned seat with a pen-knife. When his neighbour, Ernest Blythe, asked about the matter, McCarthy replied that McCartan, who he had been led to believe shared their support of the Treaty, had asked to be put down on the list of opposition speakers.[42]

Messages remained mixed in the lead-up to McCartan’s allocated timeslot. When President de Valera tried stopping the Treaty dead in its tracks on the opening day of Dáil debates, the 14th December 1921, by questioning the credentials of the Irish Plenipotentiaries in negotiating the agreement in the first place, McCartan spoke up in their defence.

“I do not think the question arises,” he said. “The Delegates had powers to conclude a Treaty. They had plenary powers and it is for us now to accept or reject what they had agreed to.” Perhaps he was remembering his own struggles to have his right to represent taken seriously in Moscow. On the other hand, six days later, on the 20th December, McCartan announced himself “as one who stands uncompromisingly for an Irish Republic.”[43]

Burying the Republic

Later that day, his turn came to rise and explain exactly where he stood. Bitter and vehement were his opening words: “It appears to me, since the opening of the Session, there has been a deliberate attempt to shirk responsibility for the way we find ourselves today,” he said, pointing a metaphorical finger of accusation:

The people elected us to direct the destinies of Ireland at this period and we elected a Cabinet. I submit it was their duty in all conditions, in all circumstances, to lead us, the rank and file, in the best possible way. I submit that they have failed.

The Plenipotentiaries were not to blame for the present disarray. That there was division at all showed the rot and how it had started from the top:

From when representatives had earlier gone to London to ascertain if Irish aspirations could be reconciled with the British Commonwealth.

From when Irishmen in the Dáil announced themselves to be not doctrinaire Republicans.

From when the Cabinet had failed to resign en masse rather than bring them all to this current point.

Because of this, and because of that, the Republic was dead. It had been sold. Partition acquiesced to with the willingness to grant Ulster exclusivity, and all this before the Plenipotentiaries had set foot inside Downing Street. This was not what men had died for. This was not what Tom Clarke died for. Clarke was the noblest of them all, a man McCartan had known intimately, and Clarke had not died for the Treaty or for Document No. 2 or External Association with Britain or Internal Association or anything of the sort. And yet that was the situation they were facing, a situation some preferred to turn away from, nursing wounded pride and resentment rather than to confront like statesmen.

Others present tried to shout him down, calling out ‘No! No!’, but McCartan would have his due:

You can contradict me when you rise to speak. I submit it is dead, and that the men who signed the document opposite Englishmen wrote its epitaph in London. It is dead naturally because it depended on the unity of the Irish people. It depended on the unity of the Cabinet. It depended on the unity of this Dáil. Are we united today as a Cabinet, united as a Dáil? United? Can you go forth after the decision is taken and say the people of Ireland are united? Can you even say the Irish Republican Army is united? You may say it is. I have my doubts. I think any thinking man has his doubts.

But, if not the Treaty, then what was the alternative? What choice could be made?

I as a Republican will not endorse it, but I will not vote for chaos. Then I will not vote against it. To vote for it I would be violating my oath which I took to the Republic, that I took to the Irish Republican Brotherhood. I never intend violating these oaths. I took these oaths seriously and I mean to keep them as far as I can. I believe just the same rejection means war. I believe every man who votes for it should be prepared for war. But you are going into war under different conditions to what we had when we had a united Cabinet, a united Dáil and a united people.[44]

The choice, then, was no choice at all in a literal sense: McCartan would neither vote for nor against the Treaty. Constituents in Edenderry, Co. Offaly, were sufficiently alarmed by their representative’s doleful words and finicky neutrality to wire him a petition, “signed by all classes and creeds”, urging him to consider his own words and get behind the Treaty, lest his withheld support amounted to its repudiation and the chaos that would surely follow.[45]

In the end, McCartan did indeed vote for the Treaty, his name – in its Irish equivalent of Pádraig Mac Artáin – appearing thirty-third on the list of sixty-four representatives in favour, against the fifty-seven naysayers. Which, Blythe believed, was McCartan’s intent from the start, his rejectionist stance which had so worried MacCarthy being an artful ploy to make the reveal of his true commitment all the more dramatic.[46]

Maybe. One could never take anything about McCartan for granted, that most quicksilver of men during this period of flux. Not for nothing did District Inspector Conlin bestow on him the highest accolade as a conspirator and most questionable trait for a co-conspirator: “Very astute and had the art of hiding his real sentiments from those to whom he did not wish to reveal them.”[47]

References

[1] Martin, F.X., ‘The McCartan Documents, 1916’, Clogher Record, Volume 6, No. 1 (Clogher Historical Society, 1966), p. 51

[2] Irish Times, 19/05/1945

[3] Ibid, 07/06/1945

[4] Ibid, 12/06/1945

[5] Ibid, 19/06/1945

[6] McCullough, Denis (BMH / WS 915), pp. 13-4

[7] Ibid, p. 14

[8] McCartan, Patrick (BMH / WS 766), pp. 40, 43-7

[9] Robbins, Frank (BMH / WS 585), pp. 118-9

[10] Military Service Pensions Collection, ‘McCartan, Patrick’ (MSP34REF56175), pp. 24-5

[11] McCullough, p. 16

[12] McCartan, pp. 49-51

[13] Coyle, Eugene (BMH / WS 325), pp. 5-6

[14] Martin, pp. 56, 58

[15] Coyle, pp. 2-5

[16] Ibid, p. 7

[17] Martin, p. 52

[18] Martin, p. 57

[19] Ibid, pp. 61-4

[20] McCartan, p. 54

[21] Corr, Seán (BMH / WS 145), p. 189

[22] Tomney, James (BMH / WS 169), p. 7

[23] ‘McCartan’ (MSP34REF56175), p. 25

[24] Robbins, pp. 116-8

[25] Ibid, pp. 139-40

[26] Ibid, p. 134

[27] Czira, Sidney (BMH / WS 909), pp. 41-2

[28] ‘McCartan’ (MSP34REF56175), pp. 25-6

[29] Martin, p. 57

[30] Ibid, p. 56

[31] Ibid, pp. 44-5

[32] Czira, pp. 42-3

[33] O’Hannigan, Donal (BMH / WS 161), pp. 32-3

[34] Robbins, pp. 138-9

[35] Irish Times, 03/11/1917

[36] ‘McCartan’ (MSP34REF56175), p. 26

[37] McCartan, pp. 64-5, 67

[38] Ibid, p. 75 ; ‘Extract from a Memorandum by Patrick McCartan on mission to Russia and on draft Russo-Irish Treaty’, Documents on Irish Foreign Policy, Volume 1, 1920, Doc. No. 33 (Accessed 11th February 1921)

[39] ‘Memorandum by Patrick McCartan on hopes of recognition of the Irish Republic from the USSR’, Documents on Irish Foreign Policy, Volume 1, 1921, Doc. No. 88 (Accessed 11th February 1921)

[40] Ibid

[41] Moylett, Patrick (BMH / WS 767), pp. 21-2

[42] Blythe, Ernest (BMH / WS 939), p. 141

[43] ‘Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922’ (accessed on the 12th February 2021) CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts, pp. 13-4, 75

[44] Ibid, pp. 79-81

[45] Irish Times, 28/12/1921

[46] ‘Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland’, p. 345 ; Blythe, p. 141

[47] Martin, p. 58

Bibliography

Newspaper

Irish Times

Bureau of Military History Statements

Blythe, Ernest, WS 939

Corr, Seán, WS 145

Coyle, Eugene, WS 325

Czira, Sidney, WS 909

McCartan, Patrick, WS 766

McCullough, Denis, WS 915

Moylett, Patrick, WS 767

O’Hannigan, Donal, WS 161

Robbins, Frank, WS 585

Tomney, James, WS 169

Article

Martin, F.X., ‘The McCartan Documents, 1916’, Clogher Record, Volume 6, No. 1 (Clogher Historical Society, 1966)

Online Resources

CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts

Documents on Irish Foreign Policy

Military Service Pensions Collection