The First Week of the Month

NEWTOWNCUNNINGHAM HORROR – IRA PARTY AMBUSHED – DEADLY FIRE BY MUTINEERS – 3 KILLED; 5 WOUNDED…

…FATAL CONFLICT IN BUNCRANA – MUTINEERS RAID A BANK – FIERCE FIGHT IN STREET – LITTLE GIRL DIES OF WOUNDS…

…SPECIALS’ POST ATTACKED – FIGHT NEAR DERRY…

…A FARM COMMANDEERED.

The multiple incidents throughout the morning of the 4th May 1922, resulting in a number of deaths and injuries in Co. Donegal, did not appear at first glance to be connected. That they were stand-alone events, independent of each other, would have been a reasonable assumption, given that these were merely a fraction of the total number of violent outbreaks that had occurred throughout Ireland in recent times.

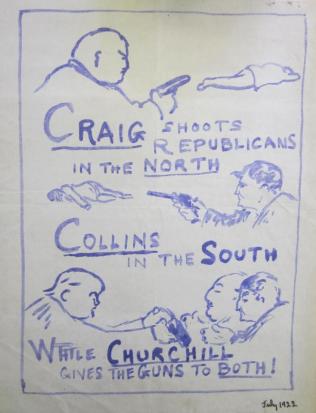

For that week alone, the Derry Journal reported scenes in Dublin, Belfast, Kilkenny, Derry, Tyrone and Mullingar. Those Ulster-based acts were due to sectarian hatreds, always simmering beneath the surface of Northern life. As for those elsewhere, more secular passions were to blame as tensions between the two rival factions within the Irish Republican Army (IRA) that had been brewing since the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January 1922 boiled over.

The four headlines above, however, differed from the others in that they had been born out of an attempt to solve both problems, burying the IRA divide by intervening together in Ulster. To the men involved, their efforts had sprung from the highest of motives and most pragmatic considerations, even as they backfired spectacularly and murderously.[1]

“A Veritable Tornado”

The Newtowncunningham incident was to receive particular attention in the weeks ahead, being subjected to the worst possible interpretations from one side and counter-accusations by the other. What did seem clear, at least, was that a motorised convoy of pro-Treaty IRA men in three Crossley lorries had driven into Newtowncunningham village, Co. Donegal, to find the walls on either side of the street lined by their opposing counterparts in the anti-Treaty IRA.

For reasons that were to be hotly debated, this encounter erupted in a gunfight, in which the Pro-Treatyites received the worst of it. One of them was killed outright in the opening fusillade, with another six injured, three seriously. The convoy sped out of the village and took its casualties to a farmhouse. From there they were able to telephone for medical help from Derry.

The doctor who responded to the call arrived minutes before two of the wounded expired, leaving him to dress the wounds of the remaining three as best he could. The sixth casualty was unavailable for treatment, having been left behind in Newtowncunningham and, presumably, now a prisoner.

The engagement lasted no more than three minutes, yet had been savage in its intensity, with one survivor describing it as a “veritable tornado.” That it was an ambush, as initially reported, would be among the details disputed.

“Amongst the ambushers was identified the leader of the party who raided the Bank in Buncrana early in the day,” added the Derry Journal, the first hint at a connection between these seemingly disparate events.[2]

Partnership

The bitter irony was that it had been to stop such fratricidal conflict that the Anti-Treatyites had been there in the first place. In the spring of 1922, a series of meetings took place between Michael Collins and Liam Lynch, the generalissimos of the pro and anti-Treaty IRA wings respectively, with a number of their close aides attending.

A lot had changed and much remained the same. In the previous year, Ireland had been a country at war between the Irish Republican forces and the British military. Now, the only areas where Crown forces remained were Dublin – from where they were due to be transferred back to Britain – and the North-East corner of the island, long a flashpoint for trouble. The Truce of July 1921 allowed the rest of Ireland to at last breathe more easily but, in the Six Counties of Ulster, violence remained a fact of life:

While the memorable truce was generally honoured in the South of Ir[eland], it will be recalled that there was no attempt made to recognise a similar situation in the North, and more specifically in the present Six Counties, Eastern Donegal and other areas close to the present border.

The Crown Forces – Tans, Ulster Special Police, etc., whether they were supposed to honour their truce or not still backed up the loyal minority of present Ulster in directing their programme in Belfast and their general reign of terror in amongst the Nationalists elsewhere.

In the face of such provocation and desperate to do something:

The General Council of the IRA decided to recognise no truce situation in the North, and ideas were exchanged as to what remedy could be applied to meet the pressure on the Northern Nationalists.[3]

So wrote Seán Lehane years later, in March 1935, in his letter to the Military Service Pensions Board. Lehane had been among those chosen to be part of the said remedy: the agreement between Lynch and Collins to send assistance up to their beleaguered Northern compatriots in the form of men drawn from the anti-Treaty party.

A Corkman with considerable guerrilla experience, Lehane was appointed the O/C of the new force. He would in turn report to Frank Aiken, the Armagh-based IRA leader, though in practice the Southerners would be acting on their own. Aiken had held himself aloof from the Treaty divisions, careful to maintain a guarded neutrality, and was thus an ideal compromise choice for Lynch and Collins.

Lehane’s instructions, as told to him by Lynch, were “to get inside the border wherever, whenever. To force the British general to show his real intention that was to occupy Ballyshannon, Sligo and along down [that direction].”[4]

Cross Purposes

That last part was a hint that the two IRA factions were not being entirely forthright with each other. The Pro-Treatyites, after all, were intending to only fight the British where they still were, not encourage them to return to areas already vacated. In contrast, such a policy reversal would suit the Anti-Treatyites perfectly, breaking the peace as it would and putting an end to what they saw as an unacceptable compromise.

As Florence O’Donoghue, one of Lynch’s confidants (who may have attended the meetings with Collins), put it:

Liam [Lynch]’s view was that, apart from the Army’s plain duty to defend our people in the North, vigorous development of activity against the Crown forces there, if supported by pro-Treaty leaders and pro-Treaty Army element in the counties along the border, would be regarded by the British as a breach of the Treaty, and would create a situation in which a re-united Army would again confront the common enemy.[5]

Which was the last thing Collins wanted. But O’Donoghue was a romantic at heart, and painted the secret pact between Lynch and Collins accordingly:

For both of them – and it was very evident there was in this project a clear objective that revived the old bond of brotherhood, a naturally shared desire to strike at the common enemy which was devoid of the heartache attaching to so many of their decisions at the time. They had, each for the other, a regard that went deeper than friendly comradeship.[6]

Such regards did not cancel out the need for discretion. For his part, Collins would contribute weapons to the venture, donated by the Pro-Treatyites to the IRA units which fell under Lynch’s direct command, and then sent up North. The Anti-Treatyites would be recompensed with weapons that had been first given to the Pro-Treatyites by their new-found British partners, who were presumably unaware as to where their gifts were earmarked.

That way, any guns that came to Britain’s attention would not be traced back to Collins, still engaged as he was in negotiations with Westminster on the implementations of the Treaty. It was a skilful meld of subterfuge and politicking, but such secrecy also ensured that the right Irish hand remained unaware what the left was doing. In time, this would prove disastrous.[7]

Opening Acts

Still, things proceeded smoothly at first. One morning in April 1922, anti-Treaty IRA men stationed in Birr, Co. Offaly, saw a flotilla of small vans pass by, their number plates from Tyrone and Derry recognisable even underneath the grime and dust from the roads. The vehicles stayed overnight, left early, and returned later that evening. It was clear from how the vans pressed down on their wheels that they now carried a considerable load – of weapons, guessed the onlookers, who remained none the wiser as to the bigger picture.[8]

Even in the heart of the anti-Treaty command, the Four Courts in Dublin, this mystery was maintained. While performing clerical duties there as part of its garrison, Todd Andrews was puzzled at the exchange of lorries with the Pro-Treatyites’ own base in the Beggar’s Bush barracks. While Andrews was dimly aware that munitions were being passed between the two sides, he saw no paperwork, and heard nothing beyond gossip and conjecture, that could account for this unexpected glasnost.[9]

For the opening moves, the leaders of the new venture met in McGarry’s Hotel, Letterkenny, having driven there the day before from Dublin. Present were Seán Lehane (Divisional O/C), Charlie Daly (Vice O/C), Peadar O’Donnell (Adjutant), Joe McGuirk (Quartermaster), Michael O’Donoghue (Divisional Engineer), Denis Galvin (Support Officer) and two other men, Seán Fitzgerald and Mossy Donnegan.

Together, they formed the command echelon of the First Northern Division, with authority over the anti-Treaty IRA units in Derry, East Donegal, South Donegal and North-West Donegal. With everyone eager to start, it was agreed to seize two positions in Co. Donegal that would serve as launch-pads into the rest of Ulster, these being Raphoe town and Glenveagh Castle in the north-west county.[10]

The former posed no difficulty. Two days later, on the 29th April 1922, the Irish Times reported how:

Unofficial [anti-Treaty] IRA forces who marched into Raphoe from the Letterkenny direction, yesterday commandeered the Masonic Hall, a solicitor’s office, and other buildings. They have fortified the buildings. The official [pro-Treaty] IRA occupy the barracks.[11]

Raphoe was now host to two different armies. Elsewhere in Ireland, such as Limerick, Athlone, Mullingar and Kilkenny, such arrangements had led to stand-offs, kidnappings and even deaths. In Raphoe, however, the two sides seemed to have co-existed amiably enough.

Moving In

Since the takeover of the Masonic Hall had been unopposed, there had been no need for violence or other unpleasantries. The IRA intruders also took over the neighbouring office of a local solicitor as he was the possessor of the keys to the hall.

“We were quite gentlemanly in our dealings with this solicitor,” recalled Michael O’Donoghue, a future GAA president and one of the ten-strong group who had entered Raphoe.

The solicitor in question handed over the keys with good grace, asking in return for some sort of written authorisation. These he duly received in the form of documents issued under the authority of the anti-Treaty IRA Executive in the Four Courts, and signed by Seán Lehane and Peadar O’Donnell as the Divisional O/C and Adjutant respectively.

The only other request from the solicitor was that he keep his silver antiques and other valuables that were in the two large glass cabinets in his bedroom (his office was adjoined to his private residence). When this was also accepted by the new occupants of the building, the solicitor duly locked the cabinets and presented the keys to O’Donoghue, complete with two copies of an inventory to be signed.

Thanks to this minimum of fuss, the new garrison was able to get to work in fortifying the Hall with sandbags before preparations could be made for the next stage in the operation. With Glenveagh Castle also taken, O’Donoghue set up his workshop there and began training select groups from each of the IRA brigade areas in his speciality of military engineering.

O’Donoghue drew up a plan for the making and assembling of mines, bombs and other explosives and left his assistant to oversee their manufacturing process, using whatever scraps of material at hand. Meanwhile, he accompanied Lehane in liaising between the various brigade areas and setting up Special Engineering Services there, no easy task considering that he was having to build from scratch.

Four brigades in Donegal and Derry were visited and reformed accordingly in the space of about ten days. The absence of bases remained a problem, with the Anti-Treatyites possessing only three barracks in its area. The rest of such buildings, now evacuated by British forces, were now in pro-Treaty IRA hands.[12]

Meeting the Opposition

The first of many problems was how the Anti-Treatyites, as in Raphoe, did not have area to themselves. Lehane and his officers may have called themselves the First Northern Division but there was already a unit with that name, whose members had decided that their place lay with the Treaty, and they far outnumbered their opposing counterparts in Donegal.

According to Lehane, writing to the press on the 10th May, a week after the tragedies, he had attempted to contact the general of the pro-Treaty forces in order to minimise the risk of the two separate Divisions butting heads.

Unfortunately, Joe Sweeney was not nearly as accommodating, and a fortnight passed without an answer. In the meantime, the Anti-Treatyites were finding themselves under constant harassment, being often held up, searched, disarmed or even detained by Pro-Treatyites.

Pressed by his subordinates to do something, Lehane finally gained a meeting with Sweeney at the latter’s headquarters in Drumboe Castle. Daly was with Lehane, while Sweeney was accompanied by his adjutant, Tom Glennon from Belfast.

“We met on friendly terms and discussed the whole position,” Lehane wrote:

I pointed out what I feared would be the outcome of the continued aggression of his forces, and made it quite plain that there were sufficient enemies of Ireland in Ulster, and that we ought to be friends.

Lehane asked Sweeney, if not assist, then at least not to hinder him in his work. Was it his intention otherwise for civil strife in Donegal? But the other man remained unmoved:

Sweeney told me he did not recognise me; that my army was an unofficial army, and that anyhow, I did not belong to the county. I replied that an Irishman was not a stranger in any part of his native land. At this stage his adjutant interjected, ‘You are our enemies.’

In the face of such a bald declaration, there was nothing else Lehane or Daly could say to make a difference, not even when Daly appealed to Sweeney on the basis of personal friendship. Their olive branch having withered, the two Anti-Treatyites withdrew from Drumboe Castle, and the situation between the two IRA factions remained frigid.[13]

Sweeney’s implacable attitude raises the question of how much he knew about the secret deal between Collins and Lynch. When interviewed years later, he described how:

Collins sent an emissary to say that he was sending arms to Donegal, and that they were to be handed over to certain persons – he didn’t tell me who they were – who would come with credentials to my headquarters.[14]

Cooperation with the Anti-Treatyites did not interest Sweeney in the slightest. When rifles arrived at Drumboe Castle in two lorries from Dublin, Sweeney was obliging enough to have their serial numbers chiselled off before smuggling some over to the IRA units in the Six Counties. He kept the rest, however, unwilling to risk them ending up in the hands of those his adjutant had proclaimed as their enemies.[15]

Secrets and Uncertainties

This would suggest that the full details of the joint-offensive deal were unknown to Sweeney. Alternatively, he may not have cared, thinking that whatever had been agreed to in distant Dublin was not relevant in Donegal. After all, for all of Lehane’s protestations of brotherhood, the Anti-Treatyites did not always conduct themselves as the model of civility.

Only a month ago, on the night of the 25th March, the pro-Treaty garrison in Newtowncunningham barracks had found themselves under attack when Anti-Treatyites arrived in a number of motorcars and, after taking up positions that overlooked the barracks, gave vent with rifles and revolvers.

As reported in the Derry Journal:

The affray, which was characterised with bloodshed, opened with a few intermittent rifle shots and developed into something in the nature of a pitched battle.

For three hours, the village inhabitants were kept awake and on tenterhooks by the crack of gunshots. When the assailants finally withdrew, having failed to take the barracks, they left behind dozens of spent cartridges.[16]

Even after the arrival of Lehane and his Munster auxiliaries, the behaviour of the Anti-Treatyites could be found wanting. When the Derry Journal and Derry Standard earned their ire, copies of those newspapers were seized by armed men from the train taking them to their retailers on the night of the 31st March, and burnt. When fresh copies were sent on a second train, this too was held up and the reprints destroyed.

One of the hijackers, noted by the Derry Journal, “spoke with a pronounced Southern accent.”

Elsewhere, parties of Anti-Treatyites were reported to be holding up cars at gunpoint in West Donegal, and either forcing the motorists to drive them elsewhere or simply taking the cars for themselves. It is perhaps unsurprising that Sweeney would be reluctant to ally with such men, let alone permit them more weapons than they already had.[17]

Plan of Action

Squeezed between the more numerous Pro-Treatyites in Donegal and the well-equipped Crown forces stationed in the Six Counties, the Anti-Treatyites were in a precarious position. Throwing to the winds his initial plan for a gradual build-up, Lehane summoned another council of war in McGarry’s Hotel in Letterkenny. There, he drew up plans for an ambitious triple-pronged night attack.

Daly was to command a sixteen-strong force, consisting of ten Tyrone and six Kerry men, to assault Molenan House, Co. Derry, which was held by about twenty Crown policemen.

At the same time, Lehane was to take the lead with thirty others against a British camp at Burnfoot that lay about five miles from Derry City. As this base was strongly garrisoned with soldiers as well as police, complete with armoured cars and machine-guns, this looked to be a daunting mission, particularly since so few of the Donegal natives involved had seen any action before, but Lehane hoped that it would at least serve as a baptism of fire for them.

The third advance was to be a robbery on the Ulster Bank in Buncrana, a village in the north of Donegal. There, they seize all the banknotes that the five-man team could find.

At the appointed time, Lehane moved from Raphoe, where his column had assembled, riding northwards in a small fleet of stolen cars. The men carried rifles and hand grenades, with revolvers and automatics for the officers. Travelling slowly along byroads, the flotilla came across a large crowd, mostly of young men, who had gathered near a road junction, eight miles out of Raphoe.

These were surrounded and searched for arms, something which they submitted to with apparent good humour. O’Donoghue felt ashamed all the same, the treatment he and his comrades were meting out reminding him too much of that by the Black and Tans he had fought against in Cork.[18]

Burnfoot

When the column neared Burnfoot Railway Station, they left their vehicles to advance more quietly on foot. It was now midnight, the designated zero hour for the operation. After some last minute instructions from Lehane, the men went about their allocated tasks.

O’Donoghue’s was to cut the telegraph cables in the station to ensure that no calls for aid could be sent to the British garrison in Derry. This O’Donoghue did with the help of a Derryman called McCourt who acted as a guide for what was for the Corkman a foreign land.

He was about to find out just how foreign.

As the pair left the station, their mission a success, a cyclist suddenly emerged out of the night towards them. O’Donoghue called out to him to halt and, when the man continued to ride on, the Corkonian – not wanting to risk a shot lest it lose them the element of surprise – grabbed him as he tried to pass by and forced him to the ground. McCourt brandished a revolver in the stranger’s face, with a demand to know his religion.

O’Donoghue was shocked:

It was my first experience of sectarian animosity in Ulster and to see an armed I.R.A. man acting like a truculent and religious bigot angered me. I turned on McCourt: “None of that” I ordered, “I don’t care a rap what his religion is and I’ll ask the questions [emphasis his].”

The frightened man was led away to be detained in the large shed where the other civilians who the column had come across were being held. With the area as secure as it could be, the IRA men checked the time and saw that it was about 1 am.[19]

Moving in two files, towards the camp two miles away in the dark, the IRA men entered a boreen that ran parallel to the main Derry road. When they found the way blocked by a waterlogged trench, the men crept carefully alongside the fences lining the boreen until they had bypassed the pool.

Nearing the Burnfoot camp, they froze when they saw lights flashing ahead of them in the distance. Some sort of message was being sent out, the men were sure, but none of them could tell what. Had they been discovered? Were the enemy alerted to their presence?

The column members pushed on regardless, being rewarded by the sight of a flickering red light that signified a fire. The British would surely not be so foolish as to leave such an obvious guide in the dark if they thought they were about to be under attack.

Emboldened, the IRA men continued along the boreen until they were overlooking the enemy camp, a hundred feet below and a hundred and fifty yards away. The column could not have asked for a better ambush site as its members carefully chose their places.[20]

The Battle at Burnfoot

The stillness of the night was shattered by a single shrill whistle-blast from Lehane, signalling the first volley from thirty or so rifles. Struggling to control his weapon’s recoil, O’Donoghue fired the full five bullets in the magazine before hurrying to reload.

In response, Verey rockets were sent up from the camp, one after another, lighting up the hillside until O’Donoghue felt as if he was beneath the spotlights of a theatre stage. Then came the rattle of machine-guns, mounted in the British armoured cars, the memory of which would be seared into his memory:

The din was terrific. Bullets whizzed overhead and thudded into the fence at our rear; they tore strips and sent splinters flying from the fence behind which we kept hunched down. Sharp crackling explosions overhead and in front – the enemy was using explosive bullets.

Outmatched in equipment and, fearing the immediate arrival of Crown reinforcements from Derry, Lehane gave the order to pull back. O’Donoghue and three others formed a rearguard, during which he was infuriated to find that ammunition and even a still-loaded revolver had been left behind, oversights that the munitions-starved Anti-Treatyites could scarcely afford.

O’Donoghue grabbed what he could and, when he judged that enough time had passed for the others to withdraw, the four of them fired a final riposte before leaving in turn. The enemy fire, having abated, returned with a vengeance from machine-guns, forcing the rearguard to crawl on their bellies until they were out of danger.

In the dark, they almost collided with Lehane, their O/C having conscientiously lingered to ensure that his four subordinates had made good their own escape. The IRA men returned to Burnfoot by daybreak and fell in for inspection. Two of them had been wounded, albeit slightly, and five had gone missing, presumably after taking a wrong turn in the dark.

Still, as the rest of the men pulled back towards Newtowncunningham, exhausted though they were, they could not help feeling jubilant at their first completed mission.[21]

Rare ‘Papishes’

The column was aided by their enemies’ misconception that it had originated from Derry, where British soldiers and police spent the morning after stopping and searching pedestrians in a futile effort to identify the assailants. Other than a grazed hand, the occupants of Burnfoot Camp had avoided casualties.[22]

When the IRA men reached Newtowncunningham in the early hour of 6 am, they took up billets in the village. Lehane, O’Donoghue and four others, all of them West Corkmen, selected a large mansion, half a mile away. Knocking on the door, they were admitted by the owner, who O’Donoghue remembered as being named ‘Black’.

As with the solicitor in Raphoe, the minimum of fuss was made. Despite his Orange-Loyalist outlook, Black played the role of gracious host as he invited his unexpected guests to a drink. Some awkward small talk was attempted, mostly about the political situation in Ulster, not that it was something any of the Corkonians could offer much about. It was something of a meeting of cultures, particularly for Black, who had never met Southern republicans before, and he was pleasantly surprised at their lack of interest in religious differences.

“To his mind, we were indeed rare ‘Papishes’,” remembered O’Donoghue.

As polite as everyone was, the IRA men were firm in their wants as they ordered no one to leave the house – a point they ensured by bolting and barring the exits – while taking the family bedrooms for their own. After a few hours of shut-eye, a messenger arrived at the door, breathlessly asking for Commandant Lehane.[23]

‘A New and Appalling Catastrophe’

Once allowed in, the newcomer told them that he was from the squad sent to Buncrana. While making their getaway from the Ulster Bank they had robbed, the IRA men had been fired upon by the pro-Treaty garrison in the village. Despite suffering a couple of wounds, the Anti-Treatyites had all escaped and were currently resting in Newtowncunningham with the rest.

For Lehane, O’Donghue and the others, there was little time to lose:

We hurriedly dressed and came down to a substantial breakfast, served by two daughters of the house with politeness and efficiency, but icily distant and formal in their manner.

After eating, the six Corkmen hurried to the village and mobilised the rest of the IRA there. A dejected Daly had also returned with his squad, having failed to take Molenon House. They had arrived to find the building locked and barricaded. After hammering on the door and shuttered windows had failed to gain entrance or even provoke the occupants – assuming there were any – into any sort of reaction, the IRA party reluctantly retired.

As Daly related this, O’Donoghue could not help but feel for his colleague:

It was an ignominious failure for Charlie to report and he felt it all the more keenly since we in Lehane’s party had fought an all-out battle.”[24]

Lehane and his officers next inspected the wounded pair from Buncrana. One had a minor leg wound, while the other, a Tipperary native called Doheny, had been shot through the lung. While a wan Doheny kept up a brave face, there was no mistaking his urgent need for medical attention. He was about to be driven to the nearby hospital but, before his comrades could do so, as O’Donoghue put it, “a new and appalling catastrophe occurred with the suddenness of a bolt from the blue.”[25]

Inquest

An inquest was held the day after on the 5th May. As it took place in the pro-Treaty IRA base of Drumboe Castle, it is unsurprising that the findings would have a certain slant.

The first witness was Colonel-Commander Tom Glennon. He told how, upon receiving word of the fighting in Buncrana on the morning of the 4th, he set off with a party of fifty men in three Crossleys and five Fords. Glennon led from the front, seated next to the driver of the first Crossley. When entering Newtowncunningham, he told the court, a man ran out from behind a wall and shouted ‘halt’.

The word was barely out when rifle rife was heard coming from both sides of the road. Deciding that to resist was suicidal, exposed as they were and outnumbered – he believed he was facing between 100 and 150 assailants – Glennon told the driver to speed on as far he could.

“You did not anticipate an attack?” asked the coroner, James Boyle.

Glennon: No; if I had, they would not have got us as easily as they did.

Boyle: You were not going to attack any person in Newtowncunningham?

Glennon: No, we were not.

Boyle: Was there anything said besides the word ‘halt’ before fire was opened on you?

Glennon: No, the shout ‘halt’ and the first volley of shots came at the same time.

Boyle: Have you heard that a man named Lehane was in charge of the attacking party?

Glennon: Yes, I heard that.

Boyle: Is he from County Donegal?

Glennon: No, he is from County Cork.

Glennon added that his men had had their rifles at straight, as opposed to at the ready which was what they would have done had they been expecting anything. In contrast, Glennon said he had seen, after driving out of Newtowncunningham, several enemy scouts positioned nearby. He concluded from this that the attack had been carefully planned.

Boyle: Is it possible that they knew you were going through to Buncrana?

Glennon: It is possible.

A member of the jury, Mr Shesgreen, was next to question the witness, asking if he knew the time of the incident. Glennon replied that it had been 6 pm.

Shesgreen: That is two hours after the truce was declared. Do you know whether the attackers got through notice from the headquarters in the Four Courts about the truce?

Glennon: I could not say. Official information did not reach Drumboe until after we left.

In a tragic postscript, an armistice between the two IRA factions had been signed that morning in Dublin between Michael Collins and Liam Lynch. It had come too late to make a difference in Newtowncunningham, however.

The three dead men – all Donegal natives – were identified as Corporal Joseph McGinley, Daniel McGill and Edward Gallagher. McGinley had had two wounds, one in his upper thigh, fracturing the bone, and the other low in the abdomen. McGill had been hit in the back and near the kidneys, while Gallagher had received two bullets to the groin.[26]

An Alternative Point of View

The pro-Treaty line was that Newtowncunningham had been a premeditated ambush, their soldiers driving obliviously into a death-trap without so much as a warning. Lehane replied to these accusations in a letter to the press on the 10th May:

With reference to the recent tragic incident…I wish to state the published accounts of the facts connected therewith misrepresents the actual circumstances of the occurrences.

By noon on the 4th May, Lehane had received word that his men in Buncrana had been “fired on without warning by a party of pro-Treaty forces, who were concealed in houses.”[27]

On this point, Lehane had a legitimate complaint as the Anti-Treatyites had been leaving the Ulster Bank in Buncrana at the time. Of course, as they had just held up the staff and robbed the bank of £8000, it was perhaps still not something that cast them in the best of lights.

Bearing the brunt of the fighting were the civilians who found themselves caught up in the crossfire. Five were wounded, some seriously. Among the victims were a father and daughter, said to be hit by the same bullet that ripped the hand of John Kavanagh before striking Mary Ellen Kavanagh (19). Peter McGowan (56) was injured in both legs, while Patrick Maguire received a flesh wound near his eye.

Of the combatants, John Doherty (24) of the Pro-Treatyites was shot in the elbow. Among the raiders, two were initially reported to have been slain, but that was erroneous. The pair were instead wounded, one thought to be seriously, though they were able to drive away with the rest of their party.

The most tragic of all was 9-year old Essie Fletcher. She was brought to Derry Infirmary with a gunshot wound in her abdomen. Surgery was quickly performed but to no avail and she died later that day.[28]

Lehane’s Version

While unaware of the full extent of the mayhem in Buncrana, Lehane knew that he had to do something. Relations with the other side had never been cordial in Donegal but now they had taken a decidedly violent turn. After consulting his officers, they agreed to move to Buncrana. He did not add in his letter to the press what he had hoped to achieve there – returning to the scene of a battle seems odd when his intentions were supposedly peaceful.

In any case, it was 6 pm by the time Lehane had mobilised his men and they were about to board their cars when a growing rumble warned of the arrival of another force. Mindful that these could be British soldiers or Crown policemen on the warpath from Burnfoot, Lehane “with a view to protecting my men…gave the order to take cover behind a broken-down fence, which was the only place available at the moment.”

Only he and Daly remained out in the open. They walked down the road to ascertain who was coming. Seeing that they were fellow IRA men, albeit of a pro-Treaty persuasion, Lehane and Daly called on them to halt.

Instead of doing so a shot was fired from the third lorry, the bullet passing over my head and smashing the fanlight of the door of a house near by, in which our wounded comrade, who had been brought from Buncrana, was then lying.

That was all the spark that was needed:

There was an immediate outbreak of fire from both forces, the pro-Treaty forces using Thompson guns as their lorries dashed though the streets. My men were ordered out on the street, as their positions were being enfiladed by fire from the lorries.

Meanwhile, the Anti-Treatyites were coming under attack from another direction. The men in the five Ford cars making up the tail of the convoy, which the Anti-Treatyites had been previously unaware, had dismounted to take shelter in a field, from where they could contribute to the shooting. Taking cover as well, the Anti-Treatyites fired back and managed to outflank the other side, forcing them back.

Lehane stressed the essentially defensive nature of his side: “On several occasions parties of them were at our mercy, but we fired only with the intention of dislodging them.”

Two Pro-Treatyites were taken prisoner after falling out of their Crossleys. One had been slightly hurt by the impact but otherwise they were unharmed. In addition to the POWs, the Anti-Treatyites took possession of two rifles, a revolver, six rifle grenades and some ammunition, as well as the Ford cars the Pro-Treatyites had abandoned in their flight.

After being brought to Raphoe, the captives told of how they had been ordered to leave their lorries and fight in the event of an attack. Lehane stressed how these two had been well-treated, the injured man tended to by a doctor, after which they were allowed to go free the next morning.

As for the truce that had come just before and too late, Lehane could plead a good excuse for not knowing of it:

Owing to our being on active service I did not get that wire until the following day, and only learned of the truce on the arrival of the Dublin papers on the morning of the 5th.

While expressing his regrets and that of his staff, and their sympathies for the families of the deceased, Lehane declared his conscience clean: “The actions and honesty of purpose of my officers and men will bear the fullest investigation.”

As for relations between the two sundered IRA wings, Lehane bore no grudges: “I am willing now as heretofore to secure an honourable understanding.”[29]

Final Rebuttals

Such a hope seemed very distant. Sweeney wrote in turn to the press, complaining at Lehane’s attempt “to make it appear that an unprovoked attack was made by our men on an inoffensive party,” as he witheringly put it.

The first shot could not have come from the third Crossley as Lehane claimed, countered Sweeney, because that vehicle had not yet appeared from around the bend before the shooting began. The fact that the Pro-Treatyites were chatting and singing while on board, Sweeney wrote, alone testified to their complete surprise.

As for the claim from the other side that they had been unsure as to who had been driving towards them:

There are people who overheard conversations of the [anti-Treaty] men in Newtowncunningham prior to the ambush prepared to state that the ambush was prepared with the full knowledge as to who were to be attacked.

As if that was not evidence enough, he continued, an Anti-Treatyite had said to one of Sweeney’s men that not only had the ambush been planned, but not enough casualties had been inflicted in his opinion.

He conceded that the prior attempt at peace talks at Drumboe Castle, as described by Lehane, had occurred. But Sweeney was adamant that:

It should be understood that as an officer responsible to GHQ of the Army of the Elected Government of the people, it did not lie within my power to arrange “a basis of unity and co-operation” with a man who absolutely repudiated the Army, GHQ, and the people’s Government.

Sweeney’s closure to his letter was both an echo and a rebuttal of Lehane’s own: “An honourable understanding may be had by the recognition of constituted authority.”[30]

‘The Attitude of Hate and Bias’

Years later, O’Donoghue would be brooding on the injustice he believed had been inflicted on him and his own. To him, that there had been a truce was particularly damning to the Pro-Treatyites who had “set out the morning after the truce to round up the IRA. The Free State officers…knew of the truce, the IRA officers did not [emphasis his].”

The underlining showed how strongly O’Donoghue felt on the matter. That the verdict from the coroner’s inquest was one of “wilful murder” was another grievance of his: “This shows the attitude of hate and bias fostered at the time by the Press in general against the Irish Republican Army.”

Regardless of the whys and whats, Lehane, O’Donoghue and a few other officers took advantage of the armistice to return to Dublin, albeit briefly – there was still work to be done in the North, after all. Lehane reported to Liam Lynch in the Four Courts on the progress made so far, while O’Donoghue was impatient to add the necessary equipment to his bomb-making workshop. The bloodshed in Newtowncunningham and Buncrana notwithstanding, they and the rest of their colleagues fully intended to continue their mission.[31]

Towards the end of the month, on the 27th May, the eighth victim of the Buncrana shootout, 19-year-old Mary Ellen Kavangh died in the Derry Infirmary. She had been shot in the upper part of her back, with the bullet lodging in her left lung. Death was ruled to be due to haemorrhage. That made her the second fatality at Buncrana, after 9-year old Essie Fletcher, and the fifth one on that unhappy day.[32]

See also:

A Death in Athlone: The Controversial Case of George Adamson, April 1922

Bloodshed in Mullingar: Civil War Begins in Co. Westmeath, April 1922

References

[1] Derry Journal, 05/05/1922

[2] Ibid

[3] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Bielenberg, Andy; Borgonovo, John and Ó Ruairc, Pádraig Óg; preface by O’Malley, Cormach K.H.) The Men Will Talk to Me – West Cork Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2015), pp. 203-4

[4] Ibid, pp. 204-5

[5] O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin: Irish Press Ltd., 1954), p. 250

[6] Ibid, p. 251

[7] O’Malley, p. 205

[8] MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), pp. 268-9

[9] Andrews, C.S. Dublin Made Me (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001), pp. 238-9

[10] O’Donoghue, Michael V. (BMH / WS 1741, Part II), p. 46

[11] Irish Times, 29/04/1922

[12] O’Donoghue, Michael V. (BMH / WS 1741), Part II, pp. 46-9

[13] Derry Journal, 12/05/1922

[14] Griffith, Kenneth and O’Grady, Timothy. Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1998), p. 275

[15] Glennon, Kieran. From Pogrom to Civil War: Tom Gennon and the Belfast IRA (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013), p. 151

[16] Derry Journal, 27/03/1922

[17] Ibid, 03/04/1922

[18] O’Donoghue, pp. 49-52

[19] Ibid, pp. 52-3

[20] Ibid, pp. 53-4

[21] Ibid, pp. 54-6

[22] Derry Journal, 05/05/1922

[23] O’Donoghue, p. 7

[24] Ibid, pp. 56-7

[25] Ibid, pp. 57-8

[26] Derry Journal, 08/05/1922

[27] Ibid, 12/05/1922

[28] Ibid, 05/05/1922

[29] Ibid, 12/05/1922

[30] Ibid, 19/05/1922

[31] O’Donoghue, pp. 61-4, 66

[32] Derry Journal, 29/05/1922

Bibliography

Books

Andrews, C.S., Dublin Made Me (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001)

Glennon, Kieran. From Pogrom to Civil War: Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

Griffith, Kenneth and O’Grady, Timothy. Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1998)

MacEoin, Uinseann. Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin: Irish Press Ltd., 1954)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Bielenberg, Andy; Borgonovo, John and Ó Ruairc, Pádraig Óg; preface by O’Malley, Cormac K.H.) The Men Will Talk to Me – West Cork Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2015)

Newspapers

Derry Journal

Irish Times

Bureau of Military History Statement

O’Donoghue, Michael V., WS 1741