‘Our National Policy’

The strategy of the anti-Treaty, or Republican, side at the start of the Civil War was defined largely by the absence of any. No less a senior figure than Ernie O’Malley, Acting Assistant Chief of Staff to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), had to write to his Chief of Staff, on the 21st July 1922, to ask him to “give an outline of your Military and National Policy as we are in the dark here in regard to both?” When Liam Lynch replied, four days later, it was in a noticeably tart tone: “You ask for an outline of GHQ National policy. Is it necessary to state that our National policy is to maintain the established Republic?”

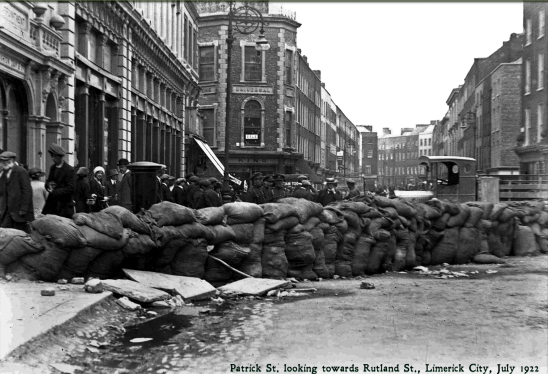

O’Malley could be forgiven for wondering how this was to be achieved. The day before, on the 20th July, IRA forces had pulled out of Limerick, forfeiting the city to the forces of the Free State, or the National Army as the pro-Treaty IRA was now to be called. With the fall of the Four Courts and other Republican bases in Dublin at the start of the month, that made Limerick the second major centre lost to the enemy, with only Cork remaining in anti-Treaty hands. In O’Malley’s eyes, things were not looking good; for Lynch, in contrast, the war had only just begun.

“We are finished with compromise or negotiations unless based on recognition of [the] Republic,” as he told O’Malley.[1]

From the start of the Treaty controversy, the two men could not have been more different, with O’Malley’s choleric aggression pitted against Lynch’s phlegmatic moderation. O’Malley had urged resistance at once without even waiting for the Dáil to finish making its decision – Lynch insisted on a ‘wait and see’ approach. O’Malley had helped bring Limerick to the point of open conflict as soon as he could – Lynch diffused the crisis with a personal intervention to the city. O’Malley had wanted to reinforce their position in the Four Courts in case of attack; by then, relations between the two factions were looking hopeful and Lynch was content to trust in the better angels of the Free State.[2]

Their respective approaches to the war before them, when it finally broke out, were similarly at odds. “Our Military Policy must be Guerrilla tactics as in late war with common enemy [Britain],” he instructed O’Malley, “but owing to increased arms and efficiency of Officers and men, it can be waged more intensely.” Business as before, in other words: what had been good against Perfidious Albion would be good enough for the Free State.[3]

O’Malley, in contrast, was quite clearly chomping at the bit as he wrote back from Dublin a week later, on the 28th July. Despite the loss of the Four Courts and other positions, the city’s IRA brigades had survived more or less intact but for how much longer, O’Malley could not say:

Enemy very active and in some cases whole coys [companies] have been picked up. This cannot be prevented, as the men must go to their daily work and there are not sufficient funds on hand to even maintain a strong column.

“We will carry on here as best we can,” O’Malley assured him, “but I am afraid we cannot bring the war home to them very effectively in Dublin.” Which is not to say a big gesture was impossible; in fact, O’Malley had a couple in mind even as he typed. “I was thinking of holding a block again for a day or two and then melting away,” he wrote. “I think the chances of melting away would be very few now but it would be better perhaps than having men and stuff picked up. Would you advise this action?”

Another bold initiative would be “to make a sweep and capture” of some of the leading figures in the Free State. Since holding them in Dublin would be difficult, given the constant enemy raids and patrols, O’Malley reached out to his Chief of Staff for help: “Could you arrange to look after them if we do not take them?”[4]

Old Tactics or New?

O’Malley had asked for advice. Five days later, on the 2nd August, writing from his current headquarters in Fermoy, Co. Cork, Lynch gave it. He hastened to throw cold water on the other man’s ambitions, stressing to his Acting Assistant Chief of Staff that the former’s main priority should be caution:

In view of the great activity of the enemy, you and other prominent officers here should take the greatest precautions. I would like to be able to rely on your safety to direct command. Keep people from seeing you – send deputies to interview those who must be seen, and direct things by dispatch.

As for O’Malley’s suggestion to temporarily seize a building block for a brief hold-out, “I would not favour this course, as it would only lead to the loss of more men, and material which we cannot afford to lose.” Similarly, while Lynch did not quite discourage the capture of high-ranking prisoners, he made it plain that O’Malley would be on his own for that one: any such POWs would have to be kept in Dublin as the situation elsewhere in the country, even in the South where the IRA’s strength was greatest, was too unsettled to be considered secure.

Instead, O’Malley was to focus his efforts on more low-key targets: sabotaging wires and telegraph poles in order to better isolate enemy posts from each other. As Lynch repeated: “I believe more effectual activities can be carried out on the lines of the old guerrilla tactics.”[5]

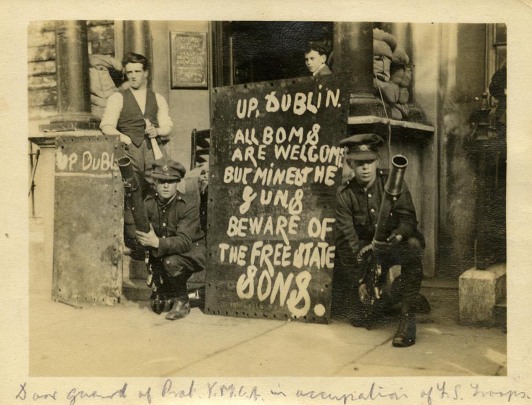

These prudent instincts seemed to receive a vindication only three days later in the crushing failure of the Dublin IRA to execute just the sort of daring stroke O’Malley had been hankering after. The ‘Bridges Job’ was intended to do nothing less than cut the Free State off at its knees by blowing up all canal and railway bridges around Dublin, effectively isolating the capital from the rest of Ireland, or at least severely impeding the ability of the enemy to reinforce or communicate with its army. Considering the number of operations the National Army was engaged in, not least its planned offensive in Munster, this wrench in its gears would have been crippling, possibly fatal.

The date of the ‘Bridges Job’ was set for the night of the 5th-6th August. Several hundred Dublin IRA men were mobilised accordingly throughout the city, some armed with handguns and grenades, others carrying the explosives and picks intended for use on their targets. Loose lips and intelligence leaks had meant that the Pro-Treatyites were forewarned, however; as the parties set forth on their mission, Free State soldiers pounced.

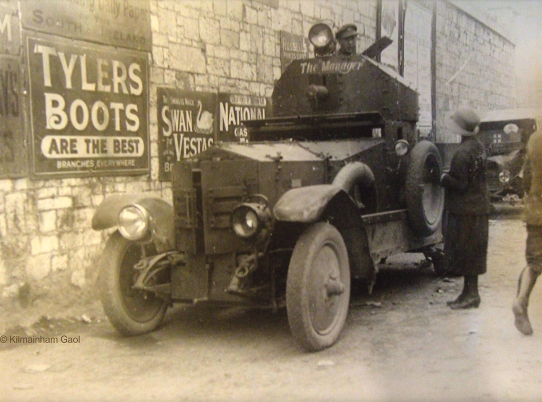

At Cabra Bridge, for example, an armoured car opened fire at point blank range, pinning down some of the IRA men in the field they had been moving through and scattering the rest. It was the same story elsewhere. “In nearly every case the Irregulars were found in the act of tearing up bridges. 104 were captured,” reported Charlie Dalton to his superiors in the National Army command. “Practically no damage was done in North County Dublin.” Likewise, in the south side, Free State troops drove out of the village of Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow, surprising IRA bands along the way. “Some succeeded in escaping but they were nearly all captured,” remembered Laurence Nugent, one of those involved. “The Republican section of the 3rd Battalion was almost wiped out.”

By this, Nugent meant captured. Other than a pair of wounded IRA fighters, bloodshed was minimum, as losing combatants in the Civil War generally preferred to surrender than battle it out to the death. But that did not lessen the scale of the disaster for the Dublin IRA, with the loss of men, some of whom were experienced officers, not to mention equipment, and never again would it take the sort of risks O’Malley wanted.[6]

Getting on with the War

The ‘Bridges Job’ was something of an anomaly since, from the start of the Civil War, the Anti-Treatyites had tended to withdraw to fight another day rather than chance an open confrontation. Which is not to say that this approach was unanimously accepted or without controversy. “There is no use in fooling with this question any longer,” Seán Moylan had told Liam Deasy impatiently on the 6th July 1922, urging the Deputy Chief of Staff to dispatch reinforcements to Limerick, where IRA forces were squaring off against their pro-Treaty counterparts, under the joint command of Donnchadh O’Hannigan and Michael Brennan. “Send on the men and let us get on with the war.”[7]

As with O’Malley later, Moylan’s push for action would be overruled. In this case, the decision had been on whether to engage at all. “O’Hannigan and Brennan Divs. are adopting a neutral attitude,” Lynch announced to O’Malley on the 10th July. “That is glorious, if they stand by their signatories.”[8]

After a series of talks in the city, both armies had agreed to a ‘live and let live’ attitude, each keeping to their respective positions and out of each other’s way. If the Union had won the American Civil War through its Anaconda Plan, using superior strength to gradually crush the Confederacy into submission, the IRA command counted on something similar to win the Irish one: isolating the scattered units of the enemy and neutralising those that could be coerced into passive ‘neutrality’ – before focusing on the holdouts. As most of the South and West were already in Republican hands, with Limerick looking to be rendered a non-threat, this appeared quite a credible stratagem. Con Moloney certainly believed so, as the IRA Adjutant General outlined to Oscar Traynor in a letter on the 9th July.

“Generally speaking we are having the best of the matter, and things are settling down to real business,” Moloney wrote. “I expect we will control say from the Shannon to Carlow in a day or two.”

Thanks to the Limerick détente, the Anti-Treatyites now enjoyed:

…a very considerable military advantage as with a comparatively small number of troops held up at Limerick, we have been able to ensure that at least 3,000 of F.S. troops are also held up. Had we to fight in Limerick our forces that are in Limerick would not only be held there for at least 10 days, but we wouldn’t be in a position to re-enforce Wexford-New Ross area.

A similar approach was hoped for in the Midlands, held on behalf of the Free State by Seán Mac Eoin, the famed ‘Blacksmith of Ballinasloe’, with:

…about 10,000 men at Athlone. It is possible that we may be able to keep McKeown [alternative spelling] neutral. In any case he is now entirely on the defensive. We expect to capture a few small posts in his area within the next week. We will have to keep him busy in any event.

Holding the enemy in place, under their thumbs, was key. The two likeliest moves the Pro-Treatyites could try, as Moloney saw it, were:

- Landing troops on the southern coast.

- Advancing into the Third Southern Division’s area (encompassing Laois, Offaly and North Tipperary).

However, Moloney told Traynor, “I think if you can keep them busy in Dublin they won’t attempt any of these, certainly not the former,” and the lack of undamaged roads should deter efforts for the latter.[9]

‘Above the Dignity of a Skirmish’

There were reasonably solid grounds for taking the picture Moloney presented at face value. The Free State position in Limerick was a weak one as O’Hannigan was painfully aware. Most of his men were raw recruits, with no more than two hundred rifles between them. Had the Anti-Treatyites chosen to attack at the start rather than talk it out, the contest would have been a short one, O’Hannigan admitted, “because we couldn’t last.” And Athlone was not much better, seeming less like a secure fortress and more like a prison, its defenders hemmed in and helpless to protect the population beyond from IRA bands.[10]

“People living in the outlying districts are in a state of terror only equalled by that experienced during the Black-and-Tan regime,” reported a local newspaper. One breakout effort apparently resulted only in failure. “Athlone attempted to march on one of our posts in 3rd Southern area, but were forced to return again to base,” Moloney reported on the 13th July. Little wonder then that “the Free State were [sic] very frightened of us” at the time, remembered Michael Kilroy, the commander of the Mayo IRA. Once Mayo was secured for the Republicans, Kilroy planned to march his troops next to Athlone and burn out the garrison from its barracks with fire-bombs made from petrol-cans. Mac Eoin, in contrast, could only fret over the poor performance of his men and wonder if it was down to their incompetence or something more insidious.[11]

“At this stage, some of our forces and some of our staff were not loyal,” he ruefully told historian Calton Younger, years later.[12]

If the war was hanging in the balance, then it tilted dramatically – but not, it must be said, decisively – in favour of the Pro-Treatyites. The truce in Limerick broke down on the 11th July and by the 20th, a little over a week later, the IRA was pulling out of the city. And Mac Eoin proved neither neutral nor defensive when he finally scored a win at Collooney, Co. Sligo, capturing the town on the 15th July after four hours of fighting. At this point, however, a Free State victory was still not inevitable, nor were the Anti-Treatyites out of the game. Collooney was something of an exception at that point, with the pace of the war being otherwise “stagnant” as the Irish Times complained: “Except in the West, where General McKeon has won a distinct and important victory at Collooney, there has been no engagement which ranks above the dignity of a skirmish.”

It should be noted that there was nothing inherently superior about the training or skill of the National Army. The Irish Times might have written enthusiastically about its new training regime on display at the Curragh and how “expert instructors in military engineering, military hygiene and medical services, tactics, training and musketry, ordnance supplies and general economic organisation, have been employed to lecture and advise the present officers and men.” But Limerick and Collooney had been won primarily, it seems, by artillery above all else. In Limerick, the Anti-Treatyites had been holding their own; some even sounded contemptuous when discussing their opponents.

“We had plenty of good fighters. The Staters were not numerous,” Tom Kelleher said, while Moloney believed that, up to the eleventh hour, “the enemy moral was very low; things were going our own way.”

Others were not so sure. “The Staters there were far better organised and in greater numbers,” said Connie Neenan. But it was surely not a coincidence that the IRA did not abandon Limerick until a heavy gun blew in the front wall of one of its barracks in the contested city. The Anti-Treatyites evacuated that night. Similarly, Collooney might well have withstood, its Republican defenders putting up “a strong resistance,” aided by four snipers in a church-tower who “kept up the firing until the shells from an 18-pounder made the position untenable,” reported the Irish Times.[13]

‘A Serious Menace to the State’

On such occasions, the Anti-Treatyites had no answer. But if ‘wonder weapons’ alone could have won the Civil War, then it would not have lasted as long as it did. Even with Limerick lost and Mac Eoin on the offensive, the situation did not look hopeless to Lynch. As for his subordinates, none of them were then advocating anything short of complete commitment to the fight. Ireland, from East Limerick to Waterford, the so-called ‘Munster Republic’, was still in in their hands, making it yet possible to formulate a plan in the face of the inevitable enemy attacks, as described by historian John Borgonovo:

Lynch intended to absorb these blows, and suck more National Army troops into Munster. Operating behind the Free State forces, IRA flying columns (well supplied with automatic weapons and mines) could then sever the government supply lines. If the Republicans failed to hold their Munster line, they would simply resume guerrilla warfare. Guerrilla warfare was what they did best, and Lynch believed the IRA would beat the Free State in a war of attrition, just as it had (in his mind) defeated the British army.[14]

This may have been a rather passive plan on Lynch’s part – true to form – but that did not make it a bad one in itself. Defending, after all, is famously easier than attacking. Lynch was counting on that military maxim to bleed the Pro-Treatyites white every step of the way out of Limerick.

“The enemy here will fail hopelessly in open country unless he advances in massed formation and that would be too costly,” he told O’Malley on the 25th July. The recent costly push by the National Army into East Limerick seemed to bear this prediction out. “We captured 76 armed prisoners and where enemy show no fight we are convinced of our future success in open country.” Little had happened by the time of another letter of his, on the 7th August, to dent his confidence: “Feel confident of victory. When will the enemy see the madness of their actions?”[15]

Only two days later, on the 9th August, it was a slightly more subdued Lynch who outlined to O’Malley the recent, most unwelcome turn of events. Someone in the National Army had evidently reached the same conclusion as Lynch in that pressing on into open country would risk too high a butcher’s bill, instead opting for an alternative route:

On the night of the 7th [August] the enemy landed at Passage (about 8 miles from Cork City), but are still pinned there and have made scarcely any progress towards Cork City. On the same night they also landed in Youghal, Union Hall and Glandore, but they do not appear to have made any attempt to advance from these points so far. Bodies of our troops have been rushed to these places to delay and contest their advances.[16]

The IRA outpost at Passage had issued some warning shots at the Arvonia as the steamer cruised towards them in the dark early hours of the 8th. When no one returned fire, the outpost men assumed it was in fact a friendly vessel. They were about to apologise at the gangway, as the Arvonia prepared for disembarkation, only to be overwhelmed by the National Army soldiers who had been biding their time on board. With their maritime entry point secure, and buoyed by their success, the Free Staters struck out that same day towards Cork City, reaching as far as Rochestown without meeting resistance.

That changed later in the evening as the men came under heavy fire, with eight of them killed. Undeterred, they pushed on and managed to reach the village of Douglas two days later. At this point, the Anti-Treatyites had largely withdrawn to nearby Cork City, where “from the display of force and the preparations made by the irregulars, it was believed that a determined effort would be made to hold the city,” according to the Irish Times.[17]

Every Man for Himself

The Anti-Treatyites, as it turned out, had a very different idea in mind. After all the drama and tension and build-up, the battle for Cork was to last no more than forty minutes, and even calling it as such would be a stretch.

Commandant-General Tom Ennis entered the city in his armoured car on the 10th August, having first lobbed a couple of shrapnel shells to disperse some lingering Anti-Treatyites at the Douglas suburb. Shots were exchanged in some of the main streets in Cork but most of the violence was directed against certain buildings as the IRA hastened to leave as little of value behind. An attempt was made to blow up Parnell Bridge, with the explosion being heard for miles around, but the structure survived, allowing Ennis and his detachment, in what the Irish Times compared to a Roman triumph, an unimpeded passage through Cork – unimpeded that is, save for the enthusiastic greetings they received en route:

Every window had its occupant waving a cordial welcome. Men cheered loudly in the streets, and when crossing Parnell Bridge the troops had to march in single file before taking up temporary headquarters at the Corn market…During their progress through the city, the troops received many a hearty hand-shake, and women embraced some of them in their joy.

The Cornmarket would have to suffice, for the military barracks in the city had been left a smouldering ruin, the fires having been started on the 8th August, almost as soon as news had come of the Passage landings, suggesting that evacuation had always been part of the Anti-Treatyites’ plan. Other barracks about the city had also been put to the torch, the hoses of the fire brigade having been spitefully sabotaged beforehand to prevent their rescue:

Dense clouds of smoke rose skywards as these buildings were being consumed, and the noise of frequent explosions gave the impression that there was heavy fighting, and it caused alarm.[18]

However frightening these sounds, there was little bite behind the bark, the men and youths who made up the IRA in Cork being more concerned with fleeing the city than fighting for it. One 18-year-old, the future writer Frank O’Connor, knew it was a lost cause when he saw a senior officer standing in the middle of a road amidst a crowd of other bewildered men, waving his arms and shouting: ‘Every man for himself!’[19]

‘An Immense Effect’

It was Limerick all over again, except the Anti-Treatyites had barely bothered with even a token resistance. Retreat at least minimalised casualties and preserved the bulk of the IRA, which was now to abandon altogether its previous attempts at holding strongpoints and territory in favour of guerrilla tactics – which was what Lynch had wanted anyway. When, on the 18th August, he announced himself to be “thoroughly satisfied with the situation now,” he was almost certainly sincere. Risking open confrontation had never sat well with the IRA Chief of Staff. “In Cork and elsewhere the organisation of Columns everywhere is complete,” he promised O’Malley, “and extensive operations will begin immediately.”[20]

The Assistant Chief of Staff was not so satisfied. As before, O’Malley was chaffing at the bit, frustrated by the enforced passivity. “We are not going to win this war on purely guerrilla tactics as we did on the last war,” he complained to Liam Deasy, O/C of the First Southern Division, on the 9th September. Instead, “we must concentrate on taking posts, as the capturing of a post, no matter how small, has a far bigger effect on townspeople and on the enemy than minor ambushing tactics.” Even better would be if this could be done in Dublin; after all, there was not much point making the country ungovernable if the Pro-Treatyites continued to hold the capital.

“If we could by means of better armament bring the war home to the Staters in the Capital,” O’Malley ruminated to Deasy, “it would have an immense effect on the people here and on the people in surrounding Counties.”[21]

Maybe. But it was far too late for that. The Anti-Treatyites had had their chance and either lost them like in Limerick, squandered them as with Cork or blew them such as the ‘Bridges Job’. From now on, the Republican cause would live or die on the guerrilla tactics Lynch put so much faith in. Had the ‘Bridges Job’ succeeded, it may very well have aborted the National Army landings in Co. Cork and elsewhere on the south coast, especially considering how the Free State grand offensive was only a few days later. Moloney had already guessed the Pro-Treatyites would attempt such a maritime assault – he had also told Traynor to keep the pressure on in Dublin to prevent just that. Munster would have remained in anti-Treaty hands and the Civil War possibly taken a different turn.

Except it didn’t, Lynch might have retorted. Speculation at that point was useless. The Anti-Treatyites had left themselves at the mercy of events, and the only thing left to do was wait and see if whatever came next would be kind.

References

[1] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007), pp. 62, 68

[2] O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), pp. 62, 71, 81, 101

[3] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 68

[4] Ibid, p.75

[5] Ibid, p. 82

[6] Dorney, John. The Civil War in Dublin: The Fight for the Irish Capital, 1922-1924 (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Square, 2017), p. 114-9

[7] Hopkinson, Michael. Green Against Green: A History of the Irish Civil War (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1988), p. 149

[8] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 45

[9] Ibid, pp. 43-4

[10] Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War ([London]: Fontana/Collins, 1970), p. 372

[11] Westmeath Independent, 08/07/1922 ; O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 52 ; O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Keane, Vincent) The Men Will Talk to Me: Mayo Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2014), p. 66

[12] Younger, p. 363

[13] Irish Times, 17/07/1922 ; MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), pp. 230, 245 ; O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 70

[14] Borgonovo, John. The Battle for Cork: July-August 1922 (Cork: Mercier Press, 2011), p. 64

[15] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, pp. 68, 88

[16] Ibid, p. 91

[17] Irish Times, 15/08/1922

[18] Ibid

[19] O’Connor, Frank. An Only Child (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1997), p. 227

[20] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 105

[21] Ibid, p. 165

Bibliography

Books

Borgonovo, John. The Battle for Cork: July-August 1922 (Cork: Mercier Press, 2011)

Dorney, John. The Civil War in Dublin: The Fight for the Irish Capital, 1922-1924 (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Square, 2017)

Hopkinson, Michael. Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 2004)

MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

O’Connor, Frank. An Only Child (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1997)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Keane, Vincent) The Men Will Talk to Me: Mayo Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2014)

O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War ([London]: Fontana/Collins, 1970)

Newspapers

Irish Times

Westmeath Independent