The Policeman

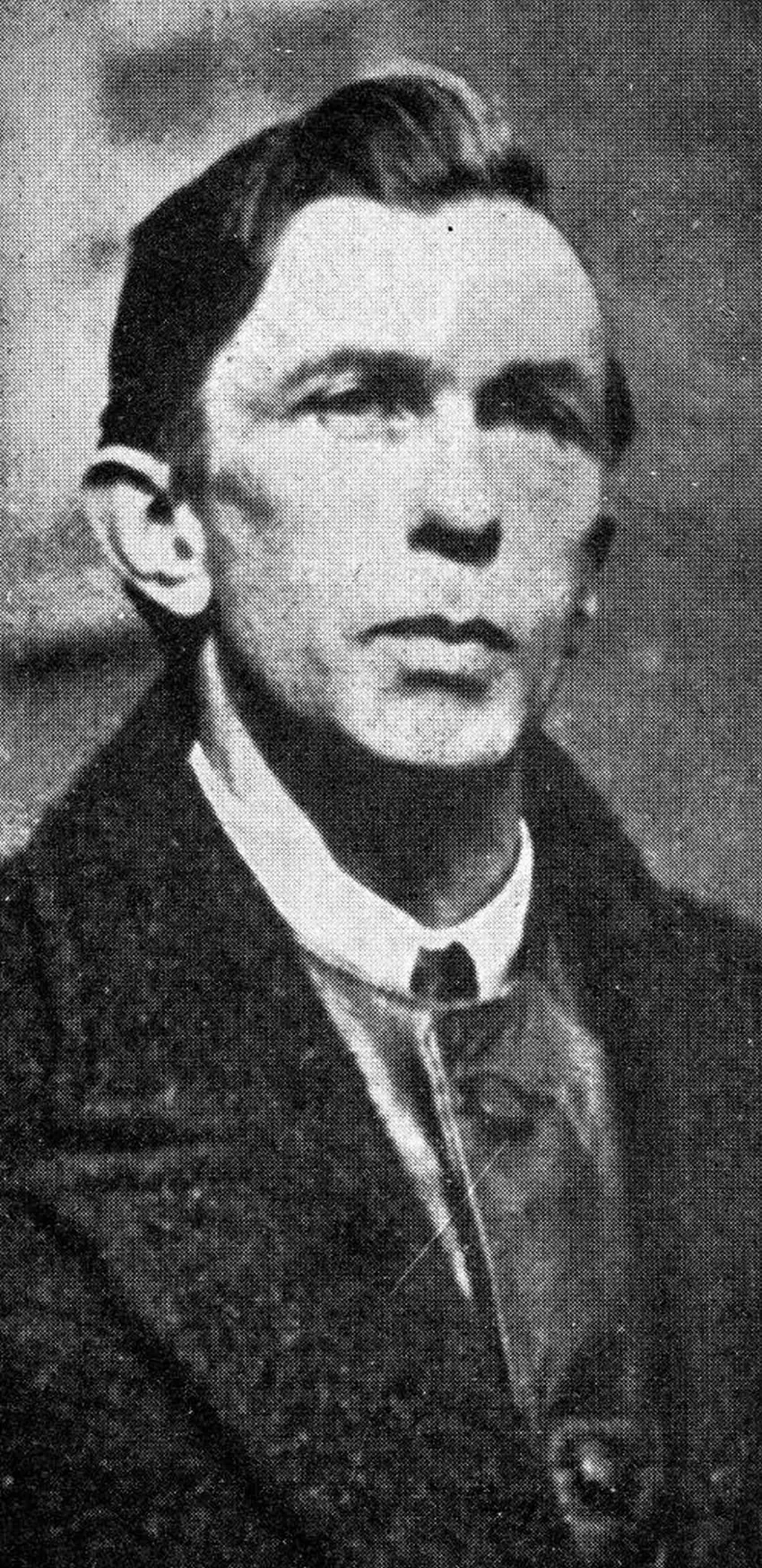

Whatever lesson his teachers intended to impart to T.J. McElligot at the training centre for the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in Phoenix Park, Dublin, it probably was not the one the young constable walked away with. “I did not know I had a country until I joined the police force at the age of nineteen,” he later wrote:

…and six months in the Dublin depot made me a rebel. On leaving the depot in May, 1908…I stood outside the gate and swore to play a man’s part in bringing that institution to an end.

It took exactly ten years and a month for such an opportunity to arise: the Military Service Act had just gone through Westminster on the 16th April 1918, meaning that the men of Ireland would soon be conscripted into doing their part for the British military machine in France and elsewhere – whether they wanted to or not. Stationed by then in Trim, Co. Meath, as a RIC sergeant, McElligot seized on the chance to act as an inside man for the protest movement that was rapidly “uniting the people of Ireland in a solid phalanx of resistance,” as he put it. By the time the Anti-Conscription Conference met in the Mansion House, Dublin, on the 18th April, two days after the passing of the Act, McElligot had been able to surreptitiously provide them with confidential police documents detailing the ways Conscription was to be enforced by the British authorities.

He hoped to go further than that:

I saw a great opportunity for defeating conscription by organising the police not to enforce it but to resist it, and that they should become the spearhead of the resistance movement.

Again, McElligot was able to use his position to good effect, contacting other RIC personnel with the plans he had in mind. When he submitted in writing his progress to the Anti-Conscription Conference, or the Mansion House Conference as it was also called, the Irish political heavyweights involved heartily thanked him for his efforts and urged him to continue.

He also reached out to the heads of the Irish Volunteers:

…and told them of the movement to resist conscription. I said it would be the greatest opportunity they could get of seizing arms in the police barracks, where they would be handed over by most men if conscription was to be enforced.

McElligot was envisioning nothing less than the mass defection of the RIC, an upheaval against Irish subservience by the very body tasked with upholding it. Given the stakes involved, and “at the time and under the circumstances,” McElligot later wrote, “I regard the conscription crisis as one of the most favourable opportunities for paralysing British rule in Ireland.”[1]

The Volunteer

The rebelliously-minded sergeant was not the only one sizing up the potential of the enfolding situation. Valentine Jackson was working for the Rathdown Rural District Council, Co. Dublin, when an officer from the British Army – by the rank of Major, Jackson believed – stopped by, asking to see the man responsible for the city streets. Jackson led him to the desk of Rory O’Connor, the Engineer of Paving. After O’Connor assured his caller that anything said would be in confidence, the Major explained the reason for his visit, saying that:

…there would be extensive street fighting in Dublin if conscription were enforced and that they would mainly use tanks, some of them of a heavy type, in such fighting. He wanted O’Connor to give him a list of streets which would be unsafe for the heaviest tanks, on account of sewers and other undergrounds works.

Playing the part of a dutiful civil servant perfectly, O’Connor asked for more information on the vehicles in question, such as their weights and load distribution, to better assess which streets would be riskiest for them. These details the Major did not know, though he promised to provide them later. The two men chatted for a while on the finer points of urban combat before the Major left, “very well pleased with the interview,” according to Jackson, who apparently had been hovering about to witness the exchange.

The Major apparently never asked himself why a pen-pusher would know so much about the logistics behind street fighting, particularly where Dublin was concerned. He might not have been so keen to confide in the obliging Irishman had he known that O’Connor had helped deliver messages to the various rebel strongpoints in the capital three years earlier, as part of the Easter Rising of 1916.

And now 1918 was looking to provide a flashpoint of its own. O’Connor called in on Jackson’s own office, located in the same building:

He wanted my opinion on a proposal that in the event of an attempt to enforce conscription the water supply should be cut off from all the city military establishments.

While sympathetic to O’Connor’s suggestion, Jackson did not think it practical, explaining that the British Army would surely be competent enough to restart water pipes in the event of them being blocked or cut. Besides, fire hydrants could be used with hose-lines to provide water if necessary.

Despite this setback, O’Connor remained:

…anxious to consider the matter further so we spent the next few days driving around the city barracks during which he noted the size and exact position of the various branch pipes together with their valves and fittings.[2]

For O’Connor just happened to be not only the Engineer of Paving for a local government body but also, in his spare time, the Director of Engineering for the GHQ of the paramilitary Irish Volunteers – memoranda on plans for the demolition of bridges, railways and engines throughout the country in the event of Conscription were signed off by him. Ernie O’Malley noticed these papers as he conversed with Michael Collins in the latter’s office on Bachelor’s Walk, Dublin, along with a large map of Ireland with red streaks radiating from the capital as plans of attack. Like O’Connor, Collins had cut his teeth during Easter Week; he also held rank in the Volunteers GHQ, as Director of Organisation, and it was in that capacity he appointed O’Malley to Co. Offaly to help lead the Volunteer companies and battalions there.

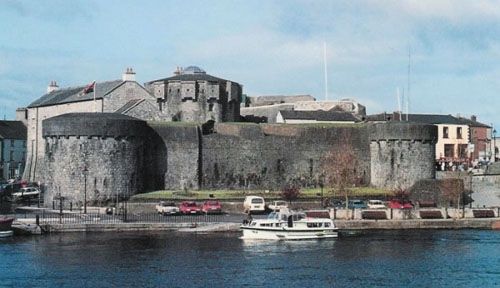

That O’Malley did to his utmost ability, parading the men through the towns and countryside while under the watchful eye of the RIC. Whenever a policeman asked his name, O’Malley would draw his revolver but it never became necessary for him to use it – at least, not yet. Elsewhere, in Athlone, an Irish sergeant-major who was part of the garrison offered O’Malley help with seizing the castle armoury, to the point of fighting his fellow soldiers if necessary.

“It looks like conscription,” Collins had told him approvingly. “That’ll make some slackers wake up.”[3]

The Activist

Even a long-time member of Sinn Féin and hardened political activist was finding it hard to process the enormity of recent events. “The past week has been a remarkable one in the history of Ireland – one of the most remarkable probably in some ways,” Liam de Róiste jotted down in his diary on the 21st April, five days after the passing of the Military Service Act. “What the effect of the decisions come to may ultimately be it is difficulty at the moment to determine.”

One thing for sure, however:

The whole nation is united, as never the nation was united before, against the imposition of compulsory service by the British Government. The right of the British Government to enforce it on Ireland is denied by all. It is accepted that the government is acting immorally, unconstitutionally, tyrannically and that, therefore, resistance to this imposition is a duty on all, is in accordance with justice, morality, religion, national right, dignity, freedom.[4]

Given the pressures on Britain on the war front, where Germany had just launched a major spring offensive, its decision to finally apply Irish Conscription may have been understandable, if desperate. Nonetheless, in doing so, it had “committed another of her many big blunders in her handling of Ireland, showing a crass lack of comprehension of the country’s outlook and reactions,” according to Kevin O’Shiel, another Sinn Féin proponent.[5]

For the separatist party, this misstep on its enemy’s part could not have come at a better time. After a flurry of success the previous year, Sinn Féin had entered 1918 with a loss of no less than three by-elections. It was enough to make O’Shiel afraid that his cause was on the retreat, and that Sinn Féin’s time had come and gone – and now the British state had given it the perfect battlefield on which to fight. From then on, for O’Shiel and his fellow party workers, “our aim was to keep the public interest up to scratch and not let it flag or fade.”[6]

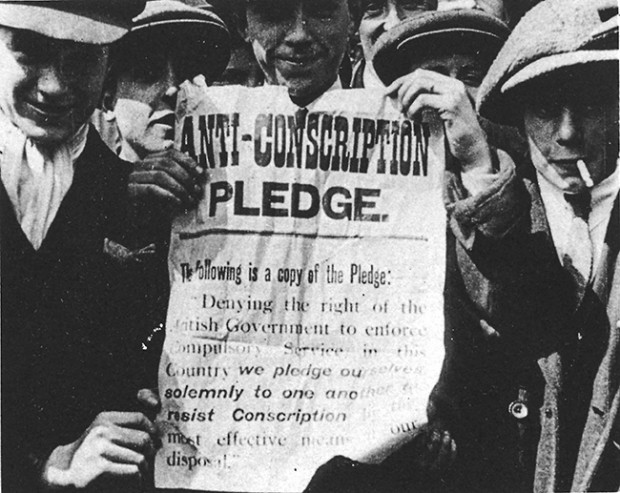

Which was unlikely to happen anytime soon. Public interest was enough for representatives from all of the major political groupings – at least where Nationalists were concerned – to meet on the 18th April 1918, at the Mansion House, Dublin: John Dillon and Joe Devlin from the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), Éamon de Valera and Arthur Griffith for Sinn Féin, along with three Labour men and two other, non-aligned Members of Parliament (MPs). After an anti-Conscription pledge was drawn up, in which the assembled leaders swore to resist the threat together, a deputation was immediately sent to where the Catholic bishops of Ireland had been gathering on unrelated matters in Maynooth. The Princes of the Church were more than happy to lend their ecclesiastical support to the political struggle, issuing a manifesto of their own later that night, declaring defiance against Conscription to be “consonant with the law of God.”

Three days later, on the 21st, meetings in almost every village and parish in Ireland were held for people to sign their names en masse to the Mansion House pledge:

Denying the right of the British Government to enforce compulsory service in this country, we pledge ourselves solemnly to one another to resist Conscription by the most effective means at our disposal.[7]

De Róiste learnt about this at Mass in St Finbarr’s Church, Cork, from no less an illustrious figure than the city bishop, the Most Rev. Dr Cohalan – a sign, de Róiste saw, of how closely the clerical and the secular would be working together on this. Also “I see the hand of Eamon de Valera in that pledge,” he later wrote, “and of Wm. O’Brien of the Labour Party in the words of ‘compulsory service,’ with the word ‘military’ omitted.” He was unwilling to give much credit to the IPP, dismissing any contribution from it “unless Parliamentarians accept Sinn Féin ideas” – as in absentionism from Westminster – “there are no others left, no others by which Conscription can be defeated.”[8]

The Politician

De Róiste was not the only one unwilling to put aside doctrinal differences even in the face of a common danger. When the idea of an anti-Conscription summit had initially been mooted at Dublin Corporation, the Labour attendees believed that this was an attempt to ‘get the jump’ on Sinn Féin, considering how everyone else in the room were IPP partisans. They would only agree to the motion if Sinn Féin was also involved – whether Sinn Féin would want to, however, was another matter.

“There appeared to be some considerable doubt as to whether they would or not,” wrote William O’Brien, one of the Labour men in question, “but finally they did. They feared they mightn’t favour the idea of working with the Irish [Parliamentary] Party.”[9]

Actually, many in Sinn Féin did not. When their central offices had received the invitation to the Mansion House from Laurence O’Neill, the Lord Mayor of Dublin and the innovator of the idea, “shrewd were the glances cast at it, and long the discussions of its worth,” described Darrell Figgis, a senior administrator in the party. De Valera and Griffith, to which the letter had been addressed, were in favour of accepting “but it took the united effort of these two men to carry the proposal with the Executive Committee,” the concern being that Sinn Féin’s sense of self as the Irish government-in-waiting would be diluted by standing next to its hated rival.

De Valera tried resorting to the suggestion that he and Griffith attend the Mansion House “as individuals, binding Sinn Fein in no way by their action,” an early display of the Long Fellow’s gift for creative ambiguity. Not that this impressed Figgis – “the suggestion was like a mathematical formula for which no practical correlative can be found – looking very real on paper, but equating with nothing real on fact” – even as he was supportive of de Valera’s stance and cynical of the motives of the naysayers. “No doubt some of these considerations were moved by the desire for separate possession and power. Impure motives move obscurely in the sincerest of folk,” Figgis wrote in his memoirs, adding darkly: “Those impure motives moved more in some than in others.”[10]

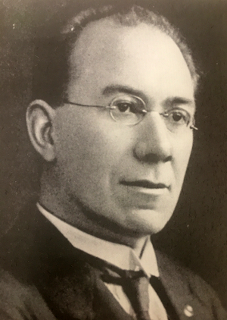

John Dillon, meanwhile, had tried talking himself out of the invite after receiving his own as the IPP Chairman, believing that the ideal place to argue Ireland’s case remained in the debating-hall of Westminster – which would just happen to play into his party’s strengths, still possessing as it did the majority of Irish parliamentary seats. The suggestion from de Valera and Griffith to the Lord Mayor that the conference go ahead without anyone from the IPP was what probably pushed Dillon into accepting, lest his party be left out in the cold.

“As I had summoned the conference,” O’Neill later explained, “I was in the chair and it took all the ingenuity I possessed to make a favourable start.” Dillon, O’Neill observed in the Mansion House, was “solemn, and no doubt realised that the power of his party was diminishing, and that by attending the conference he was playing into the hands of Sinn Fein.”[11]

Of course, the IPP’s prestige had been waning for quite some time already; in attending, Dillon had had little choice when his prevarication failed. Plenty in Sinn Féin, likewise, felt pushed into acting against their best interests. Nonetheless, “wise or unwise, the wish of the people left no alternative,” as Figgis baldly put it. Even so, the enforced familiarity with each other in no way eased the contempt between the two factions, despite the occasional attempt at solidary. One such gesture was tried at Ballaghaderreen, Co. Roscommon, when de Valera and Dillon shared a platform in early May, speaking out together against Conscription; a similar event followed in Derry, this one attended by Figgis and Joe Devlin, the Member of Parliament (MP) for West Belfast.

“Neither meeting was exactly a success,” wrote Figgis, “and they were not repeated.”[12]

The Inspector-General

It was a “union which necessity imposed on the other two parties and which is no doubt equally embarrassing to both,” wrote Sir John Byrne drolly in his monthly report to Dublin Castle. In any case, he predicted (correctly) that the makeshift alliance between Sinn Féin and the IPP would probably run aground come the upcoming by-election in East Cavan, since there could only be one seat won between the pair.

Which is not to say that the RIC Inspector-General was unconcerned or complacent about the responsibilities ahead of him; quite the contrary, in fact, as Byrne made clear:

Though prosperous and free from ordinary crime, the country early in the Month [of April] became ablaze with furious resentment on the passing of the Military Service Bill with power to apply Conscription to Ireland.

In case his employers did not fully grasp just how serious it was:

Houses were raided for arms, and explosives were stolen, and persons at public meetings spoke of shooting policemen, attacking their barracks, blowing up bridges and other acts of sabotage. For some moment some insurrectionary outbreak seemed inevitable.

Such was the danger that the more isolated RIC barracks in the south and west of the island were closed, with police in North Tipperary even confined inside at night lest they be attacked. “The County Inspector anticipates that the first attempt to enforce Conscription in the County will provoke open rebellion,” Byrne reported, “and in his opinion it will not be possible to enforce it” – a viewpoint seemingly shared elsewhere in Ireland.

What saved the day – for the time being – was “the intervention of the Roman Catholic Bishops” in their declaration:

…that England had no right to conscript the Irish people against their will and that resistance would be justifiable, but through their Clergy the people were urged to keep calm and await instructions from them and their political leaders as to united action to resist ‘this blood tax.’

While Home Rulers and Republicans were publicly working together against Conscription, it was the Catholic clergy who “now assumed command of the movement.” No better display of this dominance was the use of churches in the taking of the anti-Conscription pledge on the 21st April, and for the collection of donations for a ‘National Defence Fund’ a week later, on the 28th, the results being, according to police reports, unprecedented.

The influence of the clergy was not entirely benign from the point of view of the Inspector-General, however. “I will not I think be out of place here to call attention to the strong efforts which are being made to induce the younger members of the RIC to resign than take part in the enforcement of Conscription,” Byrne wrote. As upholders of British law in Ireland, the RIC had long been the target of abuse and suspicion, which the force had stoically weathered – until now: “It is a new experience for its members to be assailed through their conscience by members of their Church.”

The Clergyman

After all, the Constabulary recruited from the population, making the bulk of it Catholic and thus keenly vulnerable to this sort of pious blackmail:

The Clergy as a body have not openly engaged in this conspiracy to corrupt the Constabulary, but certain priests have addressed very strong appeals to them on spiritual grounds, telling them publicly in the Church that Constables who in any way assist Conscription will incur all the consequences of mortal sin, and that in the event of life being taken they will be mortally guilty of murder.

Byrne did not say how effective this subversion was, or would be if push came to shove, but the implications alone were troubling. “It is needless to point out that the preaching of such a mischievous doctrine to a religious body of men is pregnant with possibilities” [emphasis in text],” he added to drive the point home.[13]

It could be argued that, for all their undoubted influence, the Hierarchy and its priesthood had had little choice. “By the action they have taken,” observed another commentator, John Henry Bernard, the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin, “they have regained the confidence of all Roman Catholic Ireland.”

This renewed trust, combined with their unique role as spiritual counsellors, allowed individual men of the cloth to keep the peace in ways impossible for politicians or policemen. An example of this was in Cootehill, Co. Cavan, when eight men were arrested in their beds on the morning of the 16th April 1918. Four were from Sinn Féin, the other half IPP supporters, and they had brawled a month earlier over a by-election between their respective factions in Waterford City. A crowd gathered at the RIC barracks where the suspects were being held, to be told by Father P. O’Connell not to interfere with the police in the course of their duty – words evidently heeded for nothing further was done until brass bands from both the local Sinn Féin and IPP clubs arrived to parade through the town.

The fact that the two bands did so together without another incident could only be attributed to the newfound spirit of cooperation against the Military Service Act, as emphasised by the banners in the crowd reading No Conscription and We Will Not Be Conscripted. When the eight detainees were ordered to be taken to Belfast by train, Father O’Connell “directed the enormous crowd that congregated to make way for the police” escorting the prisoners to the station, “which they did,” according to the newspaper coverage.

Afterwards, at another demonstration later that day in the town square, the padre:

…delivered a rousing speech against Conscription, assuring his flock, whom he had shepherded safely through this potentially very explosive situation, that ‘they would be more than a match for the British Army’.

Perhaps no one other than an ordinary parish priest could juggle so effectively “the roles of anti-British agitator and preserver of law and order,” to quote one historian – and few other times than the Conscription Crisis would this combination have been so needed.[14]

The Relief

To some, however, all these efforts amounted to little more than empty posturing. “In sermons and from the altars the congregations were exhorted to resist conscription,” remembered Joe Good. However, “as I saw it, the clergy in Ireland were inspiring the people to a fanatical enthusiasm which they would not be able to lead or control.” Politically, leadership was defined by its absence – this was before Dáil Éireann’s creation (in January 1919), and Good clearly did not consider the Mansion House Conference or either of its component main parties, Sinn Féin and the IPP, to be adequate substitutes.

The best available were the Irish Volunteers, of which Good was one. Perhaps that is why he held a somewhat blinkered view of the situation, as if no one else in Ireland was pulling their weight, but he held that “the Volunteer GHQ had a moral responsibility for what would ensue if conscription was resisted by force of arms.” The problem was that that was easier said than done. Senior officers like O’Connor, Collins and O’Malley may have been drawing up grand strategies to their hearts’ content but Good could not recall any such plans, or any plans at all, trickling down to the ordinary rank-and-file.

Between this and their lack of weapons, the Volunteers “could only have been slaughtered” if the British military was in earnest, which Good believed they were. He saw proof of this while cycling through the country on holiday, in the form of an unusual number of railway sleepers waiting in rail yards. As a veteran of Easter Week, Good had experienced their use in war before as impromptu barricades:

There is nothing I know of quite as good. I thought I saw the plan of the British, which appeared to be to isolate a town or village, where required, by the erection of these sleeper barricades during the night so that the village could be dealt with.[15]

Good may have been speculating, but Volunteers elsewhere in Ireland were given cause to fear the worse. In Co. Tyrone, Volunteer pickets standing guard at night beheld the peculiar display of British soldiers being dropped off by train along various stations, after which the detachments would march along the rails until catching up with the train that had stopped for them. “The Volunteers could not understand what the soldier tactics meant,” recalled one witness of this, “and the incident caused much excitement and alarm and made a lot of Volunteer officers go on the run to evade capture.”

Thankfully, “this threat only lasted for a few months and then fizzled out.”[16]

Cooler heads had prevailed, both in Ireland and amongst the Powers-That-Be. “As time passed the wild consternation of the first few days gradually gave way to hope that the Government may realize the difficulties of the undertaking and not pursue it,” the RIC Inspector-General reported.

Conscription was not cancelled; at the same time, it was never implemented, almost as if London was weighing up its options, trying to figure out which was the least bad one. By October 1918, six months after the drama had begun, “the dread of Conscription subsided, and with it a good deal of the enthusiasm for Sinn Fein.” Partly this was due, in Byrne’s opinion, to “the firm attitude of Government and the support afforded to the RIC by troops stationed in disturbed districts,” but also because of the changing fortunes of the war. The German Army, once so mighty and seemingly unstoppable earlier in the year, had all but collapsed, and with it the need for Conscription.[17]

While many in Ireland (and London) must have sighed in relief, the Irish Volunteers found themselves losing much of the wind in their sails. O’Malley was in Donegal when he felt the shift in the atmosphere of the houses he visited, “an awkward silence or a sudden rush of speech… I would grope for words in return and an out-of-proportion sentence would become strain, and I would feel myself inarticulate.” It became a relief for him to take his leave.[18]

Recruits who had flocked to the safety in numbers now backed away, shrinking the Volunteers down to their prior strength. The big winner was perhaps more Sinn Féin than the Volunteers, in the opinion of John McCoy of Armagh, since the former was left well positioned to contest the subsequent General Election in November 1918. Many IPP supporters were to throw their lot in with Sinn Féin on account of its identification with the anti-Conscription campaign – although not all. “Opposed to us in this election were many of the people who had swarmed to us during the conscription crisis,” complained Michael Rock, the Commandant of the Fingal Volunteers.[19]

Truly, chewed bread is soon forgotten, as the old adage goes.

Of course, this was far from the end of the matter, for Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers with their joint mission of an independent Ireland, and for the authorities who continued to eye developments warily. Conscription had become old news already but it had, while its crisis lasted, given rise to what one long-time MP, Tim Healy, hailed as “the most remarkable movement that ever swept Ireland.”[20]

References

[1] McElligot, T.J. (BMH / WS 472), pp. 2-5, 17

[2] Jackson, Valentine (BMH / WS 409), pp. 30-1

[3] O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013), pp. 95-6, 98, 100-1

[4] ‘6 Feb – 17 May 1918’, Liam de Róiste Diaries Online, Cork City Council (Accessed on 08/02/2024), pp. 128-9

[5] O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770, Part 6), p. 10

[6] Ibid, p. 22

[7] Ibid, pp. 15-7

[8] De Róiste, pp. 127, 129-130

[9] O’Brien, William (as told to MacLysaght, Edward) Fourth the Banners Go (Dublin: The Three Candles Limited, 1969), pp. 163-4

[10] Figgis, Darrell. Recollections of the Irish War (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1927], pp. 192-4

[11] Morrissey, Thomas J. Laurence O’Neill (1864-1943) Lord Mayor of Dublin (1917-1924) Patriot and Man of Peace (Dublin: Dublin City Council, 2014), p. 109

[12] Figgis, pp. 193, 201

[13] Police reports from Dublin Castle records (National Library of Ireland – NLI), POS 8545

[14] Miller, David W. Church, State and Nation in Ireland, 1898-1921 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan Limited, 1973), pp. 408-10

[15] Good, Joseph (BMH / WS 388), pp. 38-40

[16] Corr, Seán (BMH / WS 458), p. 5

[17] NLI, POS 8545 (for April) and P8547 (for October)

[18] O’Malley, p. 118

[19] McCoy, John (BMH / WS 492), p. 37 ; Rock, Michael (BMH / WS 1398), p. 5

[20] Healy, T.M. Letters and Leaders of My Day, Volume II (London: Thornton Butterworth Ltd, [1928]), p. 597

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History Statements

Corr, Seán, WS 458

Good, Joseph, WS 388

Jackson, Valentine, WS 409

McCoy, John, WS 492

McElligot, T.J., WS 472

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

Rock, Michael, WS 1398

Books

Figgis, Darrell. Recollections of the Irish War (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1927)

Healy, T.M. Letters and Leaders of My Day (London: Thornton Butterworth Ltd, [1928])

Miller, David W. Church, State and Nation in Ireland, 1898-1921 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan Limited, 1973)

Morrissey, Thomas J. Laurence O’Neill (1864-1943) Lord Mayor of Dublin (1917-1924) Patriot and Man of Peace (Dublin: Dublin City Council, 2014)

O’Brien, William (as told to MacLysaght, Edward) Forth the Banners Go (Dublin: The Three Candles Limited, 1969)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

National Library of Ireland Collections

Police Report from Dublin Castle Records

Online Source

Liam de Róiste Diaries