A continuation of: Making Peace Out of War: The Limerick Stand-Off and the Escalation of Treaty Tensions, March 1922 (Part 1)

A Man for the World

Few personalities impacted the Civil War as much as Liam Lynch’s, to the point that it could be argued that the victory of the Free State and the defeat of the Republican cause was built on it. Contemporaries seemed to recognise this, hence the number of opinions ventured on the question of who Lynch was and what motivated him.

To Dan Breen, his fellow Anti-Treatyite “was an absolute dreamer and an idealist. He wasn’t a man for the world. A monastery was his place.” When Dublin fell to the National Army of the Free State, with the anti-Treaty Irish Republican Army (IRA) failing to muster any sort of counterattack on the capital, Breen was convinced that the war was as good as lost, and told his Chief of Staff so. But Lynch, to Breen’s frustration, refused to pay heed, which Breen blamed on the other man’s “very strong Catholic upbringing and he was stuck with it. He didn’t understand compromise.”[1]

Which was not quite fair; Lynch had spent a good deal of time in the months leading up the Civil War trying to accomplish just that – a compromise – even if it put him at odds with the rest of the IRA Executive. Lynch might have been their Chief of Staff but that did not in itself instil respect in ‘hardliners’ who dismissed Lynch, Liam Deasy and other ‘moderate’ members as “well intentioned but failing in our stand to maintain the Republic.” To Deasy, such accusations stung, especially since “we felt that our policy was consistent and meaningful.”[2]

Even a foe like Michael Brennan, a general in the National Army, could recognise Lynch’s positive qualities: “Very attractive, of unquestionable courage, the kind of man who gets others to follow him.” Having said that, Brennan, like Breen, also thought Lynch as someone not quite cut out for the rough and tumble of the real world, “an innocent sort of man.” He did not, however, equate innocence with harmlessness, nor assume that Lynch’s attempts at negotiations with Brennan in Limerick, in July 1922, were anything other than self-serving. In doing so, Lynch only sought “a free hand to overrun the country and wreck the Treaty, in spite of the people.” For all the worthy talk, Brennan did not believe the enemy Chief of Staff “had the slightest intention of ending this ‘fratricidal strife’ except on the basis of imposing his views on his opponents.”[3]

And Lynch would succeeded in doing so had he won in Limerick, for the city, in Brennan’s professional opinion, was key. “The whole Civil War really turned on Limerick,” he told historian Calton Younger, years later. “The Shannon was the barricade and whoever held Limerick held the south and the west.”[4]

In that, if little else, he and Lynch were in full agreement. “If Limerick is won it will take us a long way to upholding of [the] Republic,” he wrote to a subordinate on the 15th July 1922, as the long-stalled fighting finally broke out there.[5]

National Peace and Unity?

How Lynch intended to win the city was to vary with the circumstances. When he entered it at the start of July 1922, coming from Cashel with troops from his Cork IRA brigades, he had assumed – with the optimism that, as Deasy put, “ruled his life to the end” – he would not have to ‘win’ Limerick at all. That the place was not entirely his for the taking, with pro-Treaty forces still in possession of certain areas, was a surprise to him. Nonetheless, he set about occupying sites of his own, first the New Barracks, followed by the Strands Barracks, Castle Barracks and the Ordnance Barracks.

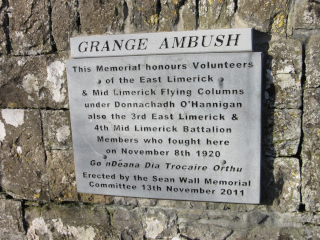

By the time Deasy joined him, Lynch was – true to form – confident that the opposition, in the form of the East Clare and East Limerick Brigades under Generals Brennan and Donnchadh O’Hannigan respectively, would be driven out in good time. Deasy could not see how this could be done and returned to his headquarters in Mallow, Co. Cork, with a heavy heart, hoping that some other way could be found to bloodlessly resolve things.[6]

Considering how anti-Treaty outposts in Dublin had been pounded with artillery only days before, that hope could not have seemed a very likely one. And so, it must have been with some surprise when Anti and Pro-Treatyites alike read the agreement Lynch and O’Hannigan had put their names to on the 4th July 1922:

- O’Hannigan will not at any time attack Executive [anti-Treaty IRA] forces, and the Executive forces likewise will not attack those of the former.

- Executive forces will not occupy any of the East Limerick Brigade’s territory.

- Both sides will only occupy their normal number of posts in Limerick City.

- That there is to be no movement of armed troops in Limerick City or East City except by liaison arrangement.

- O’Hannigan will withdraw any of his troops moved into Limerick City.

These terms were to come into effect by midnight. Though no time-limit was given, the aspiration that not only would these be lasting but would make a difference beyond Limerick, was clearly stated:

We agree to these conditions in the practical certainty that National peace and unity will eventuate from our efforts and we guarantee to use every means in our power to get this peace.[7]

‘Peace’ was the last thing on the minds of some. “There is no use in fooling with this question any longer,” Seán Moylan told Deasy impatiently on the 6th July, two days later, urging him to dispatch reinforcements to Limerick from the Kerry and Cork brigades. “Send on the men and let us get on with the war.” Though less direct in his approach, Seán Hyde was of a similar mind, warning Deasy that “if we don’t taken them on today, we’ll have to take them on tomorrow.”[8]

Had it had been Ernie O’Malley in charge, as before in March 1922, when a very similar situation unfolded in the same city, Moylan and Hyde would not have needed to ask. But Lynch was from a very different mould than the hot-headed O’Malley and, besides, he was not burdened with a divided command this time. O’Malley was preoccupied in Dublin, Séumas Robinson with Tipperary, while two others who had contrived to frustrate Lynch’s peace-making plans at every turn, Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows and Tom Barry, were cooling their heels behind bars. For once, Lynch had control of the anti-Treaty IRA all to himself, and he was going to do things his way.

Poker Face

Which could not have suited Brennan and O’Hannigan more.

Even beforehand, during the first showdown in Limerick in March 1922, the Pro-Treatyites had been stymied by the poor quality of their troops and the limited resources at their disposal; indeed, it is debatable as to whether the decision to withdraw from the city rather than fight it out with the Anti-Treatyites had been motivated more by pragmatism than pacifism. Four months later and Brennan’s situation had changed not by much. Raw recruits made up the bulk of his army, with no more than two hundred rifles between them.

Brennan could at least take advantage of his counterpart’s negligence. Lynch had overlooked the Athlunkard Bridge, allowing Brennan to secure it instead. After setting up headquarters in Cruises Hotel, Brennan established a line of posts that covered the route to the bridge. Most of the Pro-Treatyites stationed at these were unarmed, forcing them to make a display of what few arms they did have, even using lead pipes to fool hostile onlookers into thinking they had Lewis machine-guns.

Brennan could at least take advantage of his counterpart’s negligence. Lynch had overlooked the Athlunkard Bridge, allowing Brennan to secure it instead. After setting up headquarters in Cruises Hotel, Brennan established a line of posts that covered the route to the bridge. Most of the Pro-Treatyites stationed at these were unarmed, forcing them to make a display of what few arms they did have, even using lead pipes to fool hostile onlookers into thinking they had Lewis machine-guns.

As if this was not enough, Brennan managed to pull off an especially elaborate hoax. He began transporting more of his men from Ennis, Co. Clare, fifty at a time all armed with rifles. They would step off the train at Long Pavement, just across the river from Limerick, and be marched over the Athlunkard Bridge into the city. The rifles would be taken off the men and driven back by lorry to Long Pavement, where they were handed to the next batch of fifty arrivals. Brennan managed to pull this ruse several times over a couple of days.

Meanwhile, Brennan was impatiently waiting for the supplies of armaments from Dublin that he desperately needed. Looming large in his mind was the fear, as he later recalled, “that Lynch would attack me before they turned up, because we couldn’t last.” Since Anti-Treatyites had the numbers and the weapons in their favour, it was essential to use the talks with Lynch to keep his army from overrunning theirs.

“We met,” said Brennan, “and we met, altogether about a dozen times. We used to meet in the presbytery of the Augustinian church, and we argued and argued.”

Prevaricating was about the only card he could play. Except for Clare, South Galway and certain parts of Limerick, most of the South and the West were in the hands of the Anti-Treatyites. If they were to take Limerick too, then there would be nothing stopping Lynch from concentrating his forces on Dublin, where the fighting hung in the balance. At best, this would mean prolonged fighting in the capital, to be followed by the need to conquer Munster and Connaught from scratch. At worst, it would be the defeat and death of the Free State.[9]

‘A Very Grave Danger of Disaster’

Given how tenuous their position was, in Limerick and elsewhere, it was hardly surprising that morale amongst the Pro-Treatyites was “extremely low”, as Diarmuid MacManus found. “All ideas centred on (a) How best an attack from the enemy could be postponed or avoided by compromise and agreement, and (b) How long we could…hold out when besieged,” he wrote in his report to GHQ on the 7th July. That the initiative and the odds lay with the Anti-Treatyites seemed to be a given.[10]

MacManus was a new arrival to Limerick and, for Brennan and O’Hannigan, a not entirely welcome one, despite being on the same side. For one, he had been sent from Dublin on behalf of Eoin O’Duffy, their Chief of Staff, who was alarmed at what he was hearing about the rapprochement between his two generals and Lynch. Brennan and O’Hannigan, he feared, were going soft. “O’Duffy, as he was inclined to do, had jumped to conclusions,” MacManus told Younger, years later. “I imagined that he had far more information than he did, because I found when I got down there that things were not as dangerous as he had led me to believe.”[11]

In fact, MacManus at the time was as concerned as his Chief of Staff that something in Limerick was awry. “Lynch seems to have established an influence over him by soft words,” he said of Brennan in his report to Dublin. O’Hannigan, on the other hand, “is not fooled, and is the brightest spot in the situation.” Either way, MacManus shared the other officers’ fears for their vulnerability in the city. “Unless Rifles and armoured cars can arrive within 24 hours of now 10 a.m. 6/7/22,” he warned GHQ, “we will be in very grave danger of disaster.”[12]

By the end of the twenty-four hours, the requested guns and military vehicles had yet to materialise, the Free State having enough difficulty as it was keeping itself together. Neither had disaster occurred, though not from any help on MacManus’ part. The first thing he had done when arriving in Limerick, on the 5th July, was cancel the arrangement with the Anti-Treatyites. Neither Brennan nor O’Hannigan had the authority to enter into anything of the sort, he informed Lynch. There would be no more meetings between the two sides.

With that said, MacManus left Limerick for another assignment in Clare, leading Brennan and O’Hannigan to pick up the pieces. For Brennan, it was a shock to learn that his superiors in Dublin had been as bamboozled as the Anti-Treatyites in Limerick, to the point that the former “assumed that I was getting out, that I wasn’t going to support the Treaty any longer.”[13]

Either way, it did not alter the situation at hand in Limerick or lesson its danger. Knowing their combined forces were still in no state to be slugging it out, both Free State generals agreed between them on a slightly different strategy, with a new piece of paper to sign. “It was a much less specific document than the first had been,” as described by Younger. “Indeed, it was a rather odd document altogether.” Likewise, another historian, Gerald Shannon, has called it “vague and muddled in detail.”

The Second Agreement

Nonetheless, it did not lack for a certain ambition. If the first agreement was little more than a drawing of a line between the two sides in Limerick, then this one called for a conference of the divisional commandant, to be attended by:

Anti-Treaty –

- First Southern (Liam Lynch)

- Second Southern (Séumas Robinson).

- First Western (the parts under Frank Barrett).

Pro-Treaty –

- Fourth Southern (Donnchadh O’Hannigan)

- First Western (the parts under Michael Brennan).

- First Midlands Command (Seán Mac Eoin).

This conclave was to be held as soon as Mac Eoin, then based in Athlone, was available. He was another Free Stater the anti-Treaty command hoped to keep neutral and neutralised, so bringing him together with Brennan and O’Hannigan must have seemed like a chance to secure two birds with one stone. What was hoped specifically to be achieved was not stated in the document, signed by both factions on the 7th July, only that, in the event of the failure to reach a consensus, Brennan and O’Hannigan were to hand in their resignations, implying that the liability lay on them. The Anti-Treatyites, in other words, would be going in as the stronger party.

With that in mind, the details, or lack of, matter less than what it all represented: the negotiated submission of the Pro-Treatyites involved. No wonder Lynch appeared distinctly relaxed when talking again with Brennan and O’Hannigan (MacManus prohibition against further such pow-wows not being heeded). When Brennan asked what would happen if Mac Eoin refused or failed to come (after all, no one had thought to consult Mac Eoin on the matter beforehand), an unruffled Lynch replied that they would worry only if it came to it.[14]

Another measure of Lynch’s self-assurance was his letter of reply to Stephen O’Mara, the long-suffering Lord Mayor of Limerick, on the 8th July, the day after the second agreement. With civil authority at a standstill in his city, the Lord Mayor was wise enough to know who to turn to for assistance – and who held the power. Any commandeered supplies of no military value were to be returned, Lynch promised O’Mara, and while “as you weel [sic] know I cannot guarantee immediate payment for all stores retained but will see that a receipt is given for every article commandeered by us.” O’Mara’s proposal for a few IRA pickets to assist with policing would be considered; in the meantime, “I would recommend closing of Publichouses at 7 p.m. each evening and until further notice, in this I will actively co-operate.”

Clearly, Lynch was not expecting trouble anytime soon, particularly:

Now that Free State forces are evacuating Posts and removing Barricades, I have issued orders and our Posts will be evacuated by the time you receive this note. Evacuation would have been carried out up to time – 9 p.m. last evening [7th July] – were it not for other side holding up same.[15]

The note of petulance did not mar what was otherwise – to Lynch – a very promising start to the end of the war – and on his terms, no less. During their negotiations, he displayed nothing but the utmost self-confidence mixed with paternalistic concern. “His whole case was that we hadn’t the remotest chance of winning now and, as nothing could be gained by further bloodshed, could we not agree to stop it,” Brennan remembered.[16]

‘The Best of the Matter’

It was not just their Chief of Staff: many others in the anti-Treaty IRA command were likewise flush with premature victory. “Generally speaking we are having the best of the matter, and things are settling down to real business,” Con Moloney, the Adjutant General, relayed to Oscar Traynor on the 9th July. “I expect we will control say from the Shannon to Carlow in a day or two.”

Key to this winning strategy was the Limerick détente, giving them as it did:

…a very considerable military advantage as with a comparatively small number of troops held up at Limerick, we have been able to ensure that at least 3,000 of F.S troops are also held up. Had we to fight in Limerick our forces that are in Limerick would not only be held there for at least 10 days, but we wouldn’t be in a position to re-enforce Wexford-New Ross area.[17]

Two days later, the battle of Limerick began, sweeping such upbeat predictions aside. Lynch never saw it coming. “O’Hannigan and Brennan Divs. are adopting a neutral attitude,” Lynch wrote to O’Malley in Dublin, the day before, on the 10th July. “That is glorious, if they stand by their signatories.” If proved to be the operative word.[18]

Of course, to hear Brennan tell it afterwards, neither he nor O’Hannigan had any such intention. As soon as a convoy laden with long-awaited munitions arrived from Dublin on the morning of the 11th June, Brennan sent Lynch a polite note that the truce was off, and that was that. While he had never thought of Lynch as particularly brilliant, even Brennan was surprised at how easily the enemy Chief of Staff had been foxed.[19]

Years later, upon bitter reflection, some of Lynch’s subordinates would be even more contemptuous. “Liam Lynch and his bloody Truce ruined us in the Civil War,” said Frank Bumstead, while Mick Sullivan deplored the overall “’incompetence” and lack of a “military man between the whole lot of us.” More evenly, but just as damning, Seán MacSwiney pointed to “the honesty of purpose of our leaders and their belief in the honesty of purpose of the enemy” for the failure in Limerick. “Time was needed by the enemy,” MacSwiney wrote dolefully. “To gain time they gave pledge which they broke when it suited their purpose.”[20]

All accurate observations, but ones made far too late.

At the time, there was still no cause for despair or recrimination. The report on the situation, dated to the 11th July, and titled ‘Breaking of the Second Agreement’, coolly summed up the events of the day:

- At 3:30 pm, reports came in that the Free Staters were re-erecting barricades and occupying again posts they previously vacated.

- Two armoured cars and one steel-plated lorry was seen at the William Street Barracks, the main base of the enemy.

- Republican troops were ordered accordingly to occupy points of vantage not already claimed by the Pro-Treatyites.

- 5:30 – the anti-Treaty-held Ordnance Barracks came under fire from the direction of the William Street Barracks. This was the start of the fighting.

- 6:35 – information came that a pro-Treaty troop train had left Ennis for Limerick.

- 7:45 – a Free State sentry was fatally shot while attempt to disarm an anti-Treaty soldier in Roches Street.

- Firing is continuing in various parts of the city.[21]

“The second agreement reached at Limerick has been broken by the enemy,” Moloney informed O’Malley on the 13th July. “This [is] rather unfortunate at the moment as it has the effect of hold up operations against Kilkenny and Wexford-Enniscorthy Area.” Still, not to worry, was the message: “Fighting is going on in Limerick City at present and we have been able to maintain our lines of communication.”[22]

No Man’s Land

The city’s inhabitants were unlikely to be feeling quite as calm and collected. Tony McMahon remembered from his boyhood how “the area around St Joseph Street, Edward Street, Bowman Street and Wolfe Tone Street was a veritable no man’s land.” Caught between an anti-Treaty-held New Barracks and a Free State sniper atop a church tower, “the people were unable to get out to buy food and provisions,” necessitating the Anti-Treatyites to set up an emergency food depot in St Joseph Street.

“The bulk of the foodstuffs, flour, sugar, bacon and tea, were brought to the depot each morning by the troops,” according to McMahon. “There was enough for everyone and there were no complaints.”[23]

Lynch had by then withdrawn from Limerick, leaving affairs there in the hands of his subordinates. A report to him by Seán Hyde, Assistant Director of Intelligence, on the 13th July, alluded to these efforts, as well as expressing the fear that famine was a looming inevitability regardless:

The city in another day or two will be in a starving condition as the bread supply is completely cut away. We, however, are doing our best to supply the civil population without running the risk of letting the food supply fall into the hands of the enemy.

As for the military situation, Hyde wrote with a sanguinity Lynch would have been proud of:

Firing today is not so severe as it was yesterday. The Republicans continue to advance and hem in the enemy. The [IRA-held] Strands Barracks is pretty hard pressed but is sticking it splendidly…On the arrival of further reinforcements and ammunition we will guarantee good results.[24]

By the following day, the 14th, the conflict had escalated enough for Hyde to inform Lynch that “the situation in Limerick at the moment is such that fierce fighting along the whole front will be the order in the near future.” He had already suggested to Deasy, O/C of the First Southern Division, that he move some troops from his Cork and Tipperary units to clear the Free State out of Limerick, both the city and county, in their entirety, a feat Hyde did not believe would take more than a day or two. After all, “with regard to the manouvering of the enemy troops, they seem to lack leadership….If we could get them on the run at all, it would be an impossibility to rally them.”

Almost as an aside, he added: “From a reliable source we have information that the enemy has artillery in town. I cannot understand why it is not being used.”[25]

The pressure was clearly starting to get to the Assistant Director of Intelligence when he wrote the following day, on the 15th July, from the New Barracks. Hyde began by apologising for not sending the previous report even sooner as:

Really there has been a terrible rush on here since the fight started. The barrack staff have all gone out on operations, with the result that the two of us who are left here, are so muddled with calls from anywhere and everywhere that we can scarcely concentrate on anything in particular for a minute.[26]

Otherwise, little had changed – or would do so two days later in his next report, on the 17th. Both armies still held their own positions, with little progress made either way, despite how “our men continue advancing steadily, digging their way forward, but refraining from firing till the whole line is in a position to burst.” Hyde seemed satisfied with this ‘slow but steady’ approach for the moment; it was the city’s population that more concerned him: “The food question for the civil population here is becoming a very serious question.” Hyde proposed that provisions be brought in, possibly from Cork, and possibly by train.[27]

There is no indication in the replies to him that the food issue was ever considered, let alone acted on, by the rest of the IRA command. Indeed, even his request for reinforcements came up against a wall of blithe unconcern. “I consider there are already sufficient armed men in Limerick City,” the Chief of Staff replied on the 18th. It was classic Lynch: he had been underestimating the other side and overestimating his own from the start.[28]

The Blame Game

Two days later, it was all over. The artillery Hyde had heard about finally make its presence felt as well as known when, on the morning of the 20th, the Free Staters aimed such a gun at the Strand Barracks and blew in the front gate as well as a hole through the wall large enough for a horse and carriage to enter. The twenty-three men inside had surrendered by 8 pm. That was enough for the remaining Anti-Treatyites: a string of cars drove out of the city around midnight, under the cover of darkness, signalling at last the surrender of Limerick to the Free State.

Nonetheless, this was a retreat, not a rout: a rear-guard kept up covering volleys of machine gun and rifle-fire up to the last hour. Half an hour after midnight, two or three explosions ripped through the gate of the New Barracks, courtesy of a detonated mine. So strong was the blast that debris were hurled into the nearby streets, tearing the roofs off houses. As if that was not enough, two hours later, huge columns of smoke were seen billowing out from two separate locations, the New and Ordnance Barracks, and then the Castle Barracks, the flames beneath lighting up the night sky. In what would become their modus operandi, the Anti-Treatyites had set their three evacuated strongholds ablaze in order to deny the victors those gains.[29]

Had flight been necessary, or defeat inevitable? To Deasy, Lynch’s order to fall back had been entirely sensible: “He must have realised the futility of opposing artillery in street fighting.” Interestingly, Con Moloney, when writing to O’Malley five days later, on the 25th July, did not mention the enemy ordnance at all, instead attributing the loss to an imbalance of numbers: “The enemy moral was very low; things were going our own way, until enemy re-enforcements simply powered in.”[30]

While this might have been an attempt to put a brave face on an unhappy situation, another IRA combatant believed that failure could have been avoided altogether. “In Limerick we had plenty of good fighters. The Staters were not numerous,” Tom Kelleher told historian Uinseann MacEoin, in a contradiction of Moloney’s statement. “Yet attacks were not pressed when they could have been.” The failings at the top was what lost Limerick, not the men in the streets, in Kelleher’s view. Even years later, the controversy remained a live one amongst the Anti-Treatyites. “[Kelleher] blames Deasy and Lynch – I am not sure,” said Connie Neenan. “The Staters there were far better organised and in greater numbers.”

For Neenan, abandoning Limerick could not be faulted as a decision, not when the Pro-Treatyites “enfiladed fire at us from the buildings and from across the river. We were in a tight situation. In the end we had no chance against them.” The indignity instead lay with how the withdrawal had been conducted, with the men forced to fend for themselves, bereft of support and even food. By the time Neenan left, being among the last to go as part of the rear-guard, he was so hungry that he had stooped to stealing a loaf of bread. “You would think that we had never heard of Napoleon’s dictum – an army marches on its stomach,” he grumbled. When Neenan reached the town of Buttevant in North Cork that morning, “we felt hopelessly disillusioned and disheartened.”[31]

Neenan was not alone, for Limerick left a sour taste in many a mouth, even the winners’. Having held the line for so long, Brennan was shocked when Eoin O’Duffy arrived and, instead of the expected praise, openly questioned the loyalties of the former’s officers – in front of them, no less, leaving the men who had won Limerick for the Free State close to mutiny.[32]

They at least had a victory to conciliate their bruised pride. The Anti-Treatyites, on the other hand, were left with only a defeat and the sinking feeling that more were to come. The knock-on effect of the city’s loss was soon felt. East Limerick had looked ready to be conquered, Moloney told O’Malley, but “owing to the evacuation of Limerick by our Forces, the enemy in E[ast] Limerick area got a new lease of life.” Likewise, the IRA in the west of Ireland “will be pretty hard hit now that the enemy are free in Limerick.”[33]

And this was to be just the start. Lynch’s grand plan for victory was rapidly unravelling, and his dreams of a bloodless one mercilessly eviscerated by reality.

References

[1] Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War ([London]: Fontana/Collins, 1970), p. 378

[2] Deasy, Liam, Brother Against Brother (Cork: Mercier Press, 1998), p. 40

[3] Younger, pp. 374-5

[4] Ibid, p. 370

[5] University College Dublin (UCD) Archives, Moss Twomey Papers, P69/28(108)

[6] Deasy, pp. 54, 58-9, 64-5

[7] UCD, Twomey Papers, P69/28(242)

[8] Hopkinson, Michael. Green Against Green: A History of the Irish Civil War (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1988), p. 149

[9] Younger, pp. 370-2

[10] Hopkinson, p. 147

[11] Younger, p. 373

[12] Hopkinson, p. 147

[13] Younger, pp. 373-5

[14] Ibid, p. 374 ; Shannon, Gerald. Liam Lynch: To Declare a Republic (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2023), p. 200

[15] UCD, Twomey Papers, P69/28(172)

[16] Ibid, p. 373

[17] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007), p. 43

[18] O’Malley, p. 45

[19] Younger, pp. 374-5

[20] Hopkinson, p. 149

[21] UCD, Twomey Papers, P69/28(157)

[22] O’Malley, p. 52

[23] Óg Ó Ruairc, Pádraig. The Battle for Limerick City (Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Mercier Press, 2010), p. 86

[24] UCD, Twomey Papers, P69/28(141)

[25] Ibid (129-30)

[26] Ibid (107)

[27] Ibid (104)

[28] Ibid (93)

[29] Limerick Chronicle, 25/07/1922

[30] Deasy, p. 65 ; O’Malley, p. 70

[31] MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), pp. 230, 245

[32] Younger, pp. 382-3

[33] O’Malley, pp. 70-1

Bibliography

Books

Deasy, Liam. Brother Against Brother (Cork: Mercier Press, 1998)

Hopkinson, Michael. Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 2004)

MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

Óg Ó Ruairc, Pádraig. The Battle for Limerick City (Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Mercier Press, 2010)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007)

Shannon, Gerald. Liam Lynch: To Declare a Republic (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2023)

Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War ([London]: Fontana/Collins, 1970)

University College Dublin Archives

Moss Twomey Papers

The subsequent meeting was at least well attended, with the entire Brigade and battalion staff present, as was the Divisional O/C. Despite the floundering of his own efforts, O’Malley was a particularly useful addition, having spent time in Limerick as an IRA operative, and was able to fill O’Duffy in on some of the local context:

The subsequent meeting was at least well attended, with the entire Brigade and battalion staff present, as was the Divisional O/C. Despite the floundering of his own efforts, O’Malley was a particularly useful addition, having spent time in Limerick as an IRA operative, and was able to fill O’Duffy in on some of the local context:

To his shock, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) dominated the streets in a way it had ceased to do elsewhere in Ireland, its blue-uniformed sergeants and constables swaggering about “with impunity, largely because of almost complete inactivity on the part of the Volunteers in Limerick City. Apart from two or three incidents of no great magnitude, this situation persisted up to the Truce.”

To his shock, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) dominated the streets in a way it had ceased to do elsewhere in Ireland, its blue-uniformed sergeants and constables swaggering about “with impunity, largely because of almost complete inactivity on the part of the Volunteers in Limerick City. Apart from two or three incidents of no great magnitude, this situation persisted up to the Truce.”

Stepping Up

Stepping Up