A continuation from: Rebel Scout: Liam Mellows and His Revolutionary Rise, 1911-6 (Part I)

Captain Liam Mellows – in Galway – fresh from his escape is in the field with his men.

(James Connolly, in a dispatch during the fighting in Dublin, issued on the 28th April 1916)[1]

Preparations

Even in the absence of Liam Mellows, confined to England for the foreseeable future, the Irish Volunteers in Galway continued preparing for their upcoming insurrection. Plans had been announced at a convention for the Volunteers in Limerick on Palm Sunday, the 16th April 1916, when a hurling match gave the perfect cover for the delegates from the Galway, Limerick, Tipperary and Clare Volunteers to attend.

After a lengthy lecture on military tactics to put the attendees in the right mood, the Galway representatives were taken aside to a room where a map of Ireland was laid out over a table with various positions marked on it. There, it was revealed that the long-gestating Rising, the one they had been building towards all this time, was set to take place a week from then on Easter Sunday.[2]

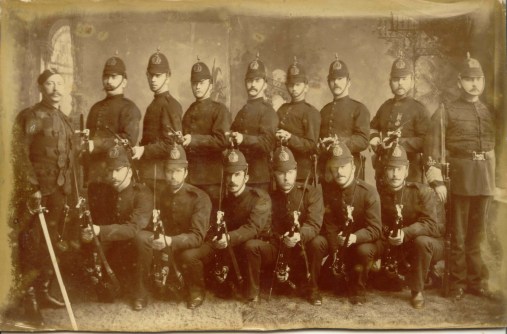

Meanwhile, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was none the wiser. The Volunteers planned on keeping it that way, right up to the moment they would march in force up to the police barracks and seize them. For that, the RIC would have no one to blame but itself. Its sergeants and constables had spent the past few months idly watching the Volunteers parade and drill in their company units, rehearsing for a revolution in plain sight without a policeman lifting a finger to interfere.

They would continue to do nothing until it was too late, until the Rising was already in unstoppable motion, until Ireland stood free of foreign rule and Saxon exploitation.

It would be child’s play.[3]

And then things grew…confusing.

Plots within Plans

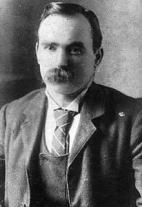

Larry Lardner, the O/C of the Irish Volunteers in Galway, had reason to feel uneasy. Sometime in 1915, he had met with a visiting Patrick Pearse while Mellows was indisposed in Arbour Hill Prison. Pearse’s purpose in Galway was to break the news about the decision to stage a rebellion. The details had yet to be formalised but would be passed on in due course to Lardner. The two had even agreed on a coded message, ‘collect the premiums’, chosen due to Lardner’s job as an insurance agent.

On Holy Monday, the 17th April, Eamon Corbett, the Vice-Commandant of the Galway Volunteers (and a future TD for the county), was dispatched to Dublin to attend a high-level meeting in St Edna’s School, which Pearse ran. Corbett returned with the orders for a countrywide uprising, to commence in six days’ time on Easter Sunday, the 22nd April. Even the precise point of 7 pm had been worked out.

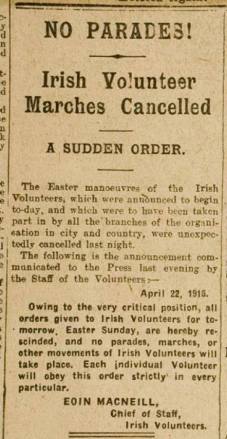

But, despite the seemingly straightforward nature of this plan, the code phrase for Lardner to ‘collect the premiums’ had not been included, leaving him unsure. His qualms were further heightened when a contradictory order arrived the following day, on the 18th April, calling off any such rebellion. As this had been signed by Eoin MacNeill, the Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers, it was not something that could be dismissed.

Unsure on how to proceed, the Galway officers held a meeting of their own in the house of a sympathetic priest, Father Harry Feeney, at Clarinbridge. The decision was made for Lardner to head to Dublin himself and get a definite answer out of MacNeill and Pearse. Arriving in the capital on Holy Thursday, the 20th April, Lardner failed to find either man, instead obtaining an interview with the next best thing: Bulmer Hobson, the Secretary of the Irish Volunteers Executive.

Doubts and Decisions

Already suspecting a divergence of opinion among the leaders of the movement, Lardner tried to ascertain from Bulmer what was going on. Bulmer’s advice him not to accept any orders that had not been approved by MacNeill. Which was straightforward enough – except that, by the time Larder returned to Galway, another dispatch was already there and waiting for him. It was from Pearse, telling him at last to ‘collect the premiums’ next Sunday on Easter Week, the 23rd April, at 7 pm.

The use of the code appeared conclusive – until the following day, on Good Friday, the 21st April, saw the appearance of yet another missive, this time from MacNeill, again calling for the Volunteers to stand down and do nothing.[4]

With Lardner paralysed by doubt, the other Galway officers approached his lieutenant, Frank Hynes, to lead them instead. Being no man’s fool, Hynes was instantly wary:

I had been ignored up to this as regards meetings of the council. I said “why do you come to me at the eleventh hour. What about Larry?” They said Larry was funking it.

Unwilling to commit himself quite yet, Hynes first went to see Lardner, finding the Brigade O/C on the verge of despair, pulled this way and that by the conflicting demands. Even consulting the Dublin headquarters had only exasperated things, Lardner complained.

After listening to his tirade, Hynes asked him point blank if he would follow the rest of the men should they marched out to fight on Easter Sunday.

“Oh, I’ll go out alright,” Lardner said.

Hynes was reassured. His commander would not be funking it, after all. But the pair of them were still not precisely clear what ‘it’ was supposed to be.[5]

Stop Press

Mellows, meanwhile, had made good his flight from England, returning to Ireland with the assistance of Nora Connolly and his brother Barney, the latter left in his place in Leeks with no one the wiser. Despite the drama and daring of the escape, the only newspaper to show interest was the Workers’ Republic – unsurprisingly so, considering how its editor was James Connolly, Nora’s father, who had sent his daughter on the rescue mission in the first place:

STOP PRESS. – RESCUE OF LIAM MELLOWS

We are at liberty to announce that Liam Mellows, the energetic Organiser of the Irish Volunteers who was recently deported to England, has been rescued, and is now safe back in Ireland.

Although this rescue took place more than a week ago the British Authorities have resolutely refused to publish the fact up to the present.[6]

Returning to Dublin gave Mellows the chance to catch up with friends, including Con Colbert, and they stayed up the whole night together singing rebel songs and having pillow-fights.[7]

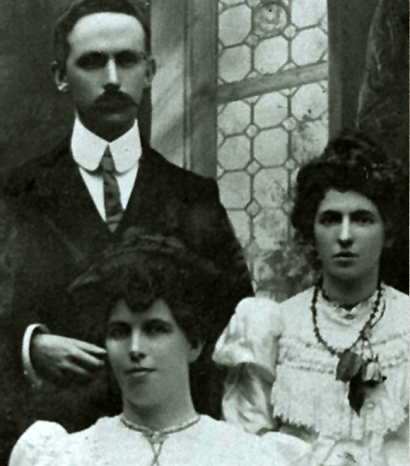

On Holy Monday, the 17th April, Éamonn Ceannt – who would soon command the Irish Volunteers in defending the South Dublin Union – suggested to his wife, Áine, that they take their 10-year-old son, Ronan, for a trip to St Edna’s. As the school was closed for the holidays, it would be quiet enough. Besides, he had no intention of remaining where he could be found and arrested anytime by the authorities.

That morning was a glorious one, with the birds singing on the branches of fruit trees in full blossom. Áine saw a smiling young man in clerical garb approach them from an avenue of trees. The ‘priest’ clasped her hand and then shook young Ronan’s.

“An aithnigheann tú é [did you recognise me]?” Mellows asked the child.

“Aithnighin [I did],” replied Ronan, who had been well-schooled in Irish.

Patrick and Willie Pearse soon joined them in the garden, along with their sister Margaret and their mother. A pleasant meal was then had, the talk ranging from books to music, with not a word said about the fight they all knew was coming.

Afterwards, Áine and her son were sent to wait in the front grounds while the men talked. When Éamonn rejoined them, it was to give his wife her instructions. It was then that Áine realised that the visit had been intended as much for business as pleasure. She was to accompany Mellow’s mother, Sarah, to St Edna’s under the cover of night for her to say goodbye to her son before he set off for Galway the following day, on the 18th April.

Áine and Sarah arrived at the school at about 9:30 pm, having changed trams four or five times on the way as a precaution. The building was in complete darkness, with not a light dared lit, as the two women were allowed in. Sarah found her way in the dark to the backroom where Liam was while Áine sat and waited in the pitch-black hall. Mother and son would not see each other again for the next five years.[8]

Road to Galway

While moving through the country, Mellows took the opportunity to pass on instructions from Dublin to the Irish Volunteer companies he met. In a detour, he informed the Wexford men of their assigned role to keep the line of communications open between the capital and Munster. Secrecy was paramount: “None of those present were told of any specific date for a rising, but all were cautioned of the very confidential nature of the discussions.”

So recalled W.J Brennan-Whitmore, another visitor from Dublin, in his memoirs. It was late at night by the time the meeting was over and Brennan-Whitmore began the trek back to the big city, where he would command the defence of the Imperial Hotel on Sackville (now O’Connell) Street. Mellows walked him to the bridge over the Slaney at the town of Scarawalsh.

“It was a beautiful night, calm and still, with a full moon riding high in the cloudless heavens,” Brennan-Whitmore remembered:

We were sitting chatting on the parapet of the bridge when the cathedral clock struck the witching hour of midnight. We decided to call it a day, shook hands and parted, he to travel to the west to take up his own command there, I to travel to Dublin. It was destined to be the last time we ever met.[9]

From there, Mellows travelled in a north-westerly direction until he reached Co. Westmeath. As in Wexford, he passed on to the waiting Volunteers their instructions, these being to blow up strategic sites such as the bridge at Shannonbridge, Co. Offaly, before advancing westwards to connect with their Galway comrades.[10]

While in Westmeath, Mellows took the opportunity to stop by the house of an acquaintance, Father Casey. Mellows had changed his usual disguise of a clergyman to that of a beggar, complete with dark dye for his distinctive fair hair. Father Casey had a nagging feeling that he knew this stranger asking for alms at his door, but it was not until his visitor had left that realisation hit him. Casey ran to the gate but Mellows was already out of sight.[11]

Return to Galway

Later, on the afternoon of Spy Wednesday, the 19th April, the Manning family in Mullagh, Co. Galway, were visited by Eamon Corbett to tell them that Mellows would be coming to stay the night with them. Corbett had arrived on foot, his motorcar having broken down, and he was given a bicycle to ride on instead.

When Mellows arrived, he was again dressed as a priest, with some greasepaint over his face, and riding on the back of a motorcycle driven by a friend from Dublin. The friend did not stay for long, leaving Mellows to the hospitality of the Mannings.

The 27-seven-year old son of the family, Michael, had seen Mellows before when the latter arrived in Mullagh in May of 1915 to inspect the Volunteers there, of which Michael was a member. Mellows spent five or six days training the men in various forms of night attack. He had planned to return later in the summer but was imprisoned instead until November.

Mellows regaled the Mannings with a lively account of his flight from Britain, chuckling at how a dockhand in Belfast had fallen on his knees to ask for a blessing, obliging Mellows to mutter something appropriately Latin-sounding. He brushed off concerns of the RIC recognising him in Galway, saying he had passed by several police barracks already without arousing suspicion.

He said nothing to the family about what he intended to do now that he was back in Galway, but the fully-loaded pistol he placed under his pillow at night and the book on military history he was carrying along with his green uniform shirt – the only luggage he had – must have given them some clue.

He did confide to Michael and his brother about the plans set for Easter Sunday. A notice to the press about a parade in Gort on the day was to be the signal for a general mobilisation of the Galway Volunteers. They would then march from Gort to Portumna, where they would be supplied with rifles sent up the Shannon from Kerry, where a German vessel was due to land with the weapons. It was a complicated plan, but Mellows was sure that their European partners would pull through for them.

Despite his cavalier attitude towards being recognised, Mellows was careful to remain indoors the following morning. He sent Michael to Loughrea with a note for Joseph O’Flaherty to alert him of his intention to spend the night there, preferably at his house. As O’Flaherty was an old Fenian and well-known to Mellows, he was delighted to oblige and sent Michael back with a message to that affect.

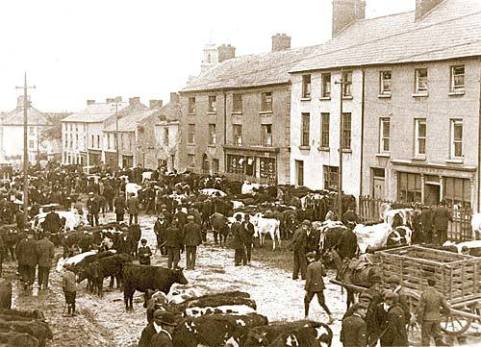

At the Manning household, Mellows swapped his priestly garb for an ordinary suit, given to him by Michael’s brother. As he left for Loughrea, he took an ash stick under his arm as if on his way to the cattle-fair that was occurring there the following day, Good Friday, the 21st April.

Michael attended the fair as part of his instructions to deliver a parcel to Mellows with his shirt and book inside. After buying and selling some cattle, Michael came to O’Flaherty’s house as arranged, found Mellows in bed and handed over the parcel.[12]

Back in Galway

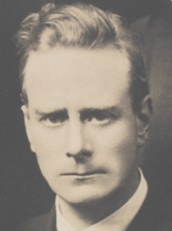

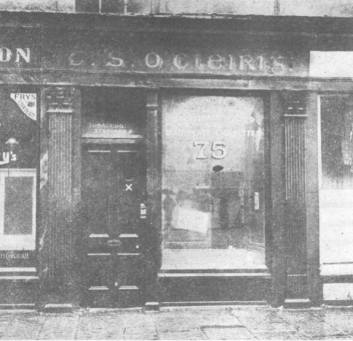

Other preparations were being made for Mellows’ return. On Maundy Thursday, the 20th April, Bridget Walsh, a schoolteacher who acted as a courier for the Volunteers, was sent to Dublin to bring back a message for him. She called in at the tobacco shop owned by Tom Clarke on Great Britain [now Parnell] Street.

Besides Clarke, Walsh met a number of leading figures in the revolutionary movement, such as Seán Mac Diarmada, Michael O’Hanrahan and Lardner, who was also visiting Dublin as part of his quest to find out what was going on. Larder told her that the rebellion in the works was now cancelled, throwing in some caustic remarks towards Eoin MacNeill and his incessant meddling.

After handing Clarke a couple of dispatches from Galway, Walsh received in return a package for Mellows. She assumed it contained a gun or ammunition, or perhaps both, and was only told later that it held the rest of Mellow’s uniform besides the shirt he was carrying.[13]

Meanwhile, back in Galway, Mellows was escorted from Loughrea by three Volunteers from the Clarinbridge Company, one of them being Patrick Walsh, Bridget’s brother. Each of the trio took turns to carry their guest on the backs of their bicycles until they reached the village of Killeenen, where Mellows was to remain at the home of Mrs Walsh, another schoolteacher and Bridget’s mother.

It was an appropriate choice of lodgings since the local battalion also used it as its headquarters. Mrs Walsh would be remembered as “a grand type of Irishwoman…She and her family were heart and soul with the Volunteers.” Her friendship with her guest was a strong one. “She adored Mellows and he held her on the highest esteem,” said one Volunteer.

For the next few nights, Volunteers were posted with revolvers on the roads leading to Walsh’s house, their instructions being to bar any suspicious-looking strangers. Until Easter Monday, when the need for secrecy could finally be cast aside, Mellows was careful to only venture out in disguise.[14]

The Mullagh Company held a hurling match on Easter Sunday, the 23rd April, as instructed by headquarters in Athenry, in order to provide cover for an address by Mellows. As before, Mellows went dressed as a priest, complete with black hair dye. When he passed one of the Volunteers, Laurence Garvey, on the road, he went as far as to ask if he recognised him. Despite Mellows having stayed at the Garvey family house while on inspection tours, Garvey replied in the negative.

When Garvey recalled Mellows’ address to the Mullagh Company, it was notable, in hindsight, in what was not said, as Garvey was sure that nowhere was anything about an insurrection mentioned. Mellows stayed until 3 pm when he left on a bicycle, accompanied by Eamon Corbett, with his audience none the wiser.[15]

Easter Sunday

Playing it by ear, Larder and Hynes allowed the Volunteers to muster as originally planned. Without telling the Athenry Company anything else, Hynes informed them they were having a parade on the morning of Easter Sunday, before attending Holy Communion as a group. Similar orders were sent out to the other companies in Galway.

Well-trained by now, the men turned out in force as ordered, many wearing bandoliers and haversacks, although only Lardner had a uniform. Having paraded, the company was starting towards the church when a bulletin came through. It was from MacNeill, and it read: No action to be taken today. Volunteers completely deceived.

After a hurried meeting by the company officers, it was agreed to issue dispatches of their own about this abrupt change of plans. There was to be no Rising after all. With that sorted, Hynes went to work the following Monday, thinking that everything had at last been settled.

He was wrong. Returning to his home for dinner, Hynes received word that he was to go to the hall used by the Volunteers. “When I went down Larry was there and his face was a placard in which trouble could be read easily,” Hynes recalled.

Lardner handed Hynes the latest written directive, this time from Pearse: Going out today at noon; issue your orders. Which could only mean one thing – the uprising was back on.

Missed Chances

At a loss for what to do, the two men ratified all the companies they could. Upon been told that Mellows was back in Galway and now staying in Killeeneen – it says much about the general state of disarray that Hynes did not seem to be aware of this already – the pair sent a message to him, asking him for instructions. His reply was that they should not do anything until he came over.

By now, everyone had heard about the fighting in Dublin. The RIC had also been caught wrong-footed but they recovered more quickly than the Volunteers. In Athenry, policemen in outlying outposts were withdrawn and concentrated in houses adjacent to the barracks, making the building too daunting to attack.[16]

One of the leading organisers for the Galway Volunteers, Alf Monaghan, was to lament the opportunities squandered in the confusion, for the RIC:

…had apparently not suspected anything, and if the original plans had been carried out, it is probable that all the barracks in the county could have been taken without a fight. In Athenry alone all the police, except one man in the barracks were at Benediction on Sunday night, and most of them went for a stroll afterwards.

So sudden had the reversal in policy been, according to Monahan, that “it is recorded that one Company actually received the countermanding order as they took up a position around the local RIC Barracks on Sunday night.”[17]

In Athenry, the only thing left for the Volunteers to do was prepare themselves in case of attack, with about a dozen of them staying in Hynes’ house on Monday night. Next morning, Lardner and Hynes made the decision to move the company towards Oranmore and unite with Mellows there. Then they would leave it to him to figure out what was what.[18]

Gathering Pace

Elsewhere in the Galway, Easter Sunday had been equally anticlimactic for the Irish Volunteers. In Clarinbridge, the Volunteers attended Mass in Roveagh village, as instructed, breakfasting afterwards on the church grounds, the food cooked by women in Cumann na mBan who were accompanying their male comrades. Mellows was present, as was Father Harry Feeney, Patrick ‘the Hare’ Callanan and Corbett as the company captain.

After several hours of waiting around, Corbett finally dismissed the men at 3 pm, telling them nothing more than not to stray far from their homes in readiness of any further mobilisations. At least one of his listeners did not take these instructions too seriously, for Martin Newell set off the next morning to Tawin village, twelve miles from his home in Clarenbridge, to purchase some seaweed.

Newell was on his way back when he met ‘the Hare’ Callanan, the Brigade Chief of Scouts, who was cycling rapidly towards him. Callanan leapt off his bike to tell Newell to hurry on to Killeeneen, for their Dublin compatriots were already in open revolt even as they spoke.[19]

It was at about 2 pm on Easter Monday, the 24th April, when it was Mellows’ turn to learn how behind in the times he was. Father Feeney rushed to the Walsh household with the news that the Dublin Volunteers had been out since noon. Galvanised, Mellows instantly sent out dispatches to as many companies in Galway as he could, ordering them to mobilise and prepare to play their part.[20]

One of the messengers sent out was Michael Kelly. He was called over to the Walsh house, where Mellows had gathered Corbett, Father Feeney and several others. Mellows asked him if he knew the area around Peterswell. When the other man replied that he did, Mellows gave him a message to take to the Ballycahan Company. Another man, Patrick Kelly (no relation), was to accompany him, each with a revolver and orders to resist should the RIC attempt to detain them.

The two men did as they were ordered, and received assurances that the Ballycahan men would be standing by. They returned to the Walsh home, only to find that Mellows and the others had already left for Clarinbridge.[21]

‘Mid Cannon Boom and the Roar of Gun

When Newell reached Killeeneen, as instructed by Callanan, he was sent by Corbett to tell the rest of the sixty-strong Clarinbridge Company to come fully armed. All the Volunteers assembled as ordered that night, with Mrs Walsh sacrificing her family’s breakfast to feed the men for supper.

At 8 am on the Tuesday, the 25th April, the Company lined up outside the Walsh house, poised on the brink of no return. Corbett performed a rousing song, with the chorus of:

Then forward for the hour has come.

To free our fettered sireland’

‘Mid cannon boom and roar of gun

We’ll fight for God and Ireland.[22]

And, with that, the men began the four mile march towards their first target of Clarinbridge. Bridget Walsh watched them as they took their leave of her mother’s house, and could not help but notice how only a few had firearms in the form of shotguns, with the rest carrying pitchforks as a primitive substitute, while uniforms were limited to a handful such as Mellows and Corbett.[23]

At least Newell was able to retrieve some stored ammunition from Killeeneen School. As he described:

We continued through the demesne and arrived at the convent gate, Clarenbridge [old spelling], where we halted and given right turn. Mellows, standing at the right-hand side of the company, addressed us. He asked for twelve Volunteers to step out. Practically the whole company stepped forward.

Spoilt for choice, Mellows picked a dozen men to act as the vanguard as the company entered the village and laid siege to the RIC barracks there. First blood was shed when a policeman was caught outside and shot when he reached for his revolver. As the Volunteers were in a merciful mood, and the county not yet embittered by years of conflict, the wounded constable was removed to the convent for medical treatment.

The attack on the barracks was interrupted when the parish priest, Father Tully, came to remonstrate with Mellows, urging him to cease and desist. Mellows refused unless the RIC men surrendered and asked Tully to convey this to the barracks. The priest did so, but the policemen inside declined and the attack resumed.[24]

Clarinbridge

Michael and Patrick Kelly followed in their wake, meeting other Volunteers posted as sentries a mile outside the village, from where they heard the sounds of gunfire. “The attack was still going on when we arrived,” Michael remembered. “The whole company was there, all firing at the barracks at a range of about fifty yards.”

There was a barricade on the Oranmore Road made of Mineral water boxes, with Volunteers behind the barricades to prevent reinforcements from reaching the barracks. All the approaches to the village were barricaded and all traffic held up. About midday or 1 p.m. the attack was called off.

“Mellows was in full charge,” Michael stressed. Other than the constable at the start, it had been a bloodless battle: “No Volunteer was wounded. There was no RIC man wounded inside Clarenbridge barracks during the attack.”

Seeing how they were only wasting time and bullets, Mellows ordered the barricades to be taken down. The Volunteers departed for Oranmore village, where they met up with two more companies, the Oranmore and Maree ones, who had already made an unsuccessful attempt on the RIC there. As with Clarinbridge, the police garrison were holed up inside the barracks, with the exception of their sergeant, trapped in another building in the village.

Mellows decided to continue the assault despite receiving news of police reinforcements on the way to Oranmore by train. He sent for Michael Kelly and Michael Cummins, assigning the former to the station to see if the enemy had arrived yet and, if so, in what strength. As for Kelly:

He sent me to the forge near the Sergeant’s house with a section of about six men with instructions not to allow the Sergeant to leave his house. The Sergeant made no attempt to leave his own house.[25]

The Connacht Tribune gave the officer in question a slightly more heroic role – unsurprisingly, given how it was Sergeant Healy who told the newspaper the story. Healy had been one of the two policemen out on patrol that morning, leaving four constables behind in the barracks.

When Healy saw the two companies of Volunteers advancing towards Oranmore, he was careful to take a circuitous route along the sea coast to avoid detection while returning to the village (the other RIC man, Constable MacDermott, being not so cautious, was taken prisoner). By the time Healy arrived, the Volunteers were already there, with his four subordinates fortified within their barracks.

Lacking any other options, Healy retreated to the house of Constable Smyth, opposite the barracks. He watched as about thirty-five Volunteers rushed the barracks, only to be driven back by rifle-shots from inside.

As the Connacht Tribune reported:

Immediately Sergeant Healy had got with the shelter of Constable Smyth’s house, he sent orders across to the men in the barracks as to how they were to act and communications were sent to Galway for reinforcements.

Half an hour later, one of the assailants came to Smyth’s door and demanded the surrender of everyone inside. When Mrs Smyth insisted that there was no one else present, the men grew menacing. Healy warned the messenger at the door to go or he would fire.

Instead, the Volunteers began battering at the door until Healy shot through the panels, forcing them to flee down the street. They did not return, contenting themselves instead with taking potshots at the barracks.[26]

Flight

Cummins, meanwhile, had ridden his bicycle to the station and found that enemy reinforcements had already pulled in, one of whom missing a shot at Cummins as he peddled rapidly away to warn the others. Michael Kelly later numbered the RIC to around forty. More precisely, the Connacht Tribune put the Crown relief force down to twenty-two – ten policemen under the overall command of the County Inspector, and ten soldiers from the Connaught Rangers, including their captain.

Together, they marched at a smart pace towards Oranmore, scattering the villagers who had been drawn outside their homes by the novelty of a siege. An attempt by the Volunteers to disable a bridge on the way was abandoned, the discarded crowbars testifying to the speed of their flight.

Upon nearing the barracks, the mixed police-military force came briefly under fire by shotguns and rifles from the turn of the road leading to Athenry. This rebel rearguard then departed from Oranmore with the rest of their compatriots in commandeered motorcars.

“The whole random affair appears to have been over in less time than it takes to write it,” sniffed the Connacht Tribune.

According to Newell, Mellows:

…was the last to leave and took cover at the gable of Reilly’s public-house until the RIC arrived in the village from the station and, when they were about to enter the RIC barrack, he opened fire on them with, I think, an automatic pistol from a distance of 25 yards.

In Kelly’s version, he, Cummins and a few others had remained behind with their leader after Mellows had ordered the rest of the three companies to withdraw towards Athenry. The soldiers and policemen took cover beside the houses on either side of the road and did not retaliate, waiting instead for their assailants to leave.

Though bullet had whizzed perilously close to the County Inspector’s head, no harm was done, the only police loss being the missing MacDermott, believed (accurately) to have been captured. Not wishing to linger lest the rebels return with their superior numbers, Sergeant Healy and his remaining four constables left Oranmore by train with their rescuers after first stripping anything of value from the barracks.[27]

Carnmore

It was dark by the time the three Volunteer companies arrived at the Agricultural School, about a mile out of Athenry. Close as it was to a railway line by which further British forces could arrive, the School was not an ideal stop but, for want of anywhere else, Mellows decided to make it his temporary headquarters. The companies from Athenry, Craughwell, Newcastle, Derrydonnell and Cussane trickled in throughout the night, with the Castlegar and Claregalway men arriving in the Wednesday morning of the 26th April.[28]

The last two had been fetched by Callanan. After being dispatched by Mellows on Monday evening, he had been in a whirlwind of activity, successfully rousing the Volunteers in Castlegar and Claregalway, as well as those in Maree and Oranmore. Galway City was a failure, however, as Callanan was unable to get in touch with anyone from the Volunteers there. As for the Moycollen Company, its captain promised Callanan that he would mobilise his men and also pass on word to the Spiddal Company. He failed to do either, but Callanan had other things to worry about by then.

Callanan returned in time to find Mellows and the Clarinbridge Company marching towards Oranmore. Mellows assigned him to go back and bring the Claregalway and Castlegar men to join him in Oranmore. By the time Callanan and the two companies arrived, the Crown relief force was already present and holding the bridge, blocking any attempt to follow in the wake of Mellows’ group.

Luckily, Callanan was able to learn that the main force was in the Agricultural School. As it was too late to journey to Athenry, he billeted his men in nearby Carnmore. Having first posted watchmen on the village outskirts, Callanan settled in for the night until awoken by gunshots.

The sentries had opened fire on a convoy of six or seven cars coming from the direction of Galway City. The vehicles pulled up by the road and their RIC occupants exchanged shots with the Volunteers sheltering behind stone walls.

Meanwhile, Callanan was hastily assembling the rest of his men, before they beat a hasty retreat out of Carnmore. The police did not pursue, instead driving forlornly back to Galway City with the corpse of Constable Patrick Whelan, a bloody hole in the side of his head, the 34-year-old native of Kilkenny being the sole fatality of Galway’s Easter Rising.[29]

The Agricultural School

A second shootout with the RIC occurred later on Wednesday morning when the sentries posted in a hut on the Agricultural School grounds were surprised to see a group of seven policemen advancing up the road with rifles primed. Alerted to the threat, Hynes set out with six others. They opened fire on the RIC who withdrew back towards Athenry, returning shots as they did so.

Hynes, Lardner and the rest of the Athenry Company had reunited with Mellows the night before at the School. When composing his story for posterity years later, Hynes would feel an acute need to address the question he was sure lurked in the heads of his readers:

Anyone reading this account would be inclined to think that we were acting in a rather cowardly manner – why did we not attack the barrack at Athenry? Why did we keep retreating, etc, etc?

The explanation he gave was that while the Volunteers numbered between five and six hundred, they had only fifty full service rifles between them, with the rest of the army having to make do with shotguns, inferior .22 rifles and a dozen pikes. Ammunition was equally scarce, and some men were not armed at all. Bombs had been made, but these were so useless that Hynes doubted they would injure a man even if they exploded in his hand.[30]

Alf Monahan took an equally sceptical view on their chances: “Over 500 men assembled at the [Agricultural School], but a great part of them had no firearms of any sort. In fact, there were only 35 rifles and 350 shotguns, all told.”

As for the plan to land three thousand German rifles in Co. Kerry, to be moved by rail and distributed all along the line to Galway to the eagerly waiting Volunteers, that lay in tatters, ruined by a fatal combination of the gun-running ship being unable to unload, the arrest of Roger Casement and the accidental drowning in Kerry of the three Volunteers (one of whom, Charles, was Alf’s brother) who were to distract the Royal Navy with fake radio signals.

Despite this grievous setback and the equally worrying paucity of weapons, morale remained high. “All were in the best of humour and full of pluck,” remembered Monahan.[31]

Some of the men present had not even been in the Irish Volunteers before but were showing their willingness to contribute, whether for the national cause or more acrimonious reasons. Bridget Walsh described how a pair of Connemara men offered their services on the grounds that: “If you are going sticking peelers [policemen] we are with you.”[32]

Moyode Castle

Lardner was present as Brigade O/C but Mellows was undoubtedly the one in command. At a council of war, it was suggested by the officers present that their small army be divided into columns with which to wage a guerrilla war, but this was unanimously rejected. Instead, the decision was made to move on to Moyode Castle, five miles away.

As they left the Agricultural School, Mellows confided to Callanan his determination to never yield, not while there was still a scrap of hope. Help was likely to arrive soon, he added, with the Volunteers of Limerick and Clare sure to rally to their aid.[33]

Practically empty save for a single caretaker, Moyode Castle posed no difficulty in capturing. It was, in Monahan’s view, “not a good place to put in a state of defence, as there were large windows all around it.” Still, it was at least roomier than the School had been, allowing for the various companies to be allocated their own quarters. They had by then collected five RIC prisoners, who were kept under watch.[34]

The next morning, on the Thursday of the 27th April, Mellows drove out with several others on a reconnaissance mission, calling on a number of houses to inquire after any enemy movements. Upon nearing the New Inn RIC Barracks, Mellows decided to risk further investigation. They found it had been evacuated except for two women, who told Mellows that they were the only ones there. When Mellows said he would give the building a search all the same, one of the women, visibly nervous, admitted that her husband, the barracks sergeant, was there after all, being ill in bed upstairs.

According to Stephen Jordan, one of the other Volunteers present (and another TD-to-be), “Mellows then requested her to go to the room and tell her husband that he wanted to ask him some questions, and to tell him not to be anxious as no harm would come to him.”

Jordan accompanied his leader into the bedroom, where Mellows questioned the sergeant about the size of the former garrison and where they would have left for. The stricken policeman replied that they had received an order to go to Loughrea and the rest had departed before daybreak, taking everything of value with them.

“The Sergeant seemed very relieved on account of Mellows’ gentlemanly manner,” remembered Jordan. “We returned to Moyode without further incident.”[35]

Fight

An incident was had, however, later that day, when Mellows assigned Jordan to lead a foraging party. They went to a farm at Rahard and were loading two carts with potatoes – with or without the owner’s permission was left unstated in Jordan’s later account – when a body of policemen pedalled into range on bicycles. Both sides reached for their weapons and opened fire, the sounds enough to reach Moyode Castle and prompt a rescue party of two or three carloads of Volunteers to drive out immediately.

By the time these reinforcements, headed by Mellows, arrived on the scene, the RIC had fallen back. After Jordan delivered a brief summary of what had transpired, Mellows gathered the men back into their cars and set off in pursuit of the police, who retreated further as fast as they could, reaching the safety of Athenry before the Volunteers could overtake them.[36]

Not so easily vanquished was the booming of artillery from the direction of Galway Bay as a British battleship, the HMS Gloucester, tried unsuccessfully to fix a target on the rebel base. The sounds were heard as far as the Castle throughout Wednesday to Friday, with the Volunteers deciding that this was from a duel between the Royal Navy and German submarines. Regardless of how their ‘gallant allies in Europe’ had failed in delivering the much-missed rifles, the Galway men could still entertain the hope that they were not fighting alone.

“The Moyode garrison was well equipped with rumour,” Monahan recalled dryly, but there was nothing known for sure about what was happening in Dublin or the rest of the country.[37]

Other than during the potato-hunting foray, there were no sightings of any police or soldiers, though that did not prevent talk of an imminent attack. Even years afterwards, that such gossip came about at all still grated on Hynes:

We will give the bearers of these false rumours the charity of our silence, but one in particular who was responsible for most of them was a very prominent republican and a member of the I.R.B. up to Easter Week. This man did his best to get us to give up and go home and have sense. He brought one particular rumour that five or six hundred soldiers were marching on us from Ballinasloe.

A meeting of the officers was called on the strength of this particular warning. Much to Hynes’ shame, one or two of those present were sufficiently unnerved to openly consider the naysayer’s advice to quit and return home, so disgusting Mellows that he handed over command to Lardner, who probably wanted the responsibility least of all.

An hour was enough for Mellows to calm down and resume authority. He made his way through the castle, talking to the men and answering any entreaties as to the situation. They could hold out for a month, he told them, by moving south to the Clare Hills.

Flight

This was too much for some. When Monahan addressed the Volunteers on Thursday night, offering anyone with second thoughts the chance to leave, about two hundred – roughly a third of the force – decided to do so. They first gave up their weapons, overcoats and anything else of use to those staying, though some of these waverers returned the following day.[38]

By then, the Volunteers had been stirred into action when a scout returned with the news of nine hundred British troops on the march towards the Castle. Unlike previous reports, this one was broadly accurate, as anyone with a copy of the Connacht Tribune would have read of how:

We regret to say that we at last (for good or ill) now approaching the conditions of a regular trial of military strength as between the Crown forces and what, we suppose, may be described as the Insurgents.

Information was vague, admitted the newspaper; indeed, it wildly overestimated the rebels to be two thousand-strong. More certain was of the aim of the British State: “It was known last [Friday] night that the authorities intended to take the initiative.” Royal Navy marines had landed in Galway Bay, their strategy seeming to be to join the rest of the military in catching the said insurgents with a pincer-move.[39]

There was no question inside Moyode Castle of allowing this to happen, and the debate arose again as to whether it would be better to disband or retreat in good order. The latter was decided on, and Mellows arranged the companies in marching order. Never afraid to risk himself, he took charge of the Athenry Company, alongside Corbett and Hynes, which was assigned to be the rearguard, where fighting was most likely to break out should the British forces catch up with them.

The Volunteers marched along by-roads to the east of Craughwell, making it to Monksfield by nightfall. The plan was to reach Co. Clare and obtain enough help from the Volunteers there to fight their way to Limerick, where further reinforcements hopefully awaited.[40]

Amongst the rearguard, Michael Kelly saw that they were being tailed by two men on bicycles. All he could make of them was that they were dressed in black. Kelly ordered the other men to take cover while he called on the strangers to halt. The pair were riding so fast that they sped straight into the midst of the Volunteers before they could stop.

Up close, Kelly could see that they were priests. When the two asked to see Mellows, a suspicious Kelly questioned them closely, learning that their names were Father Fahy and Father O’Farrell. He was not certain but he thought he caught something from them about Dublin.[41]

Turbulent Priests

Father Thomas Fahy first met Mellows when the latter arrived in Galway, early in 1915. When Fahy, then a professor at Ballinasloe College, had asked Mellows if the Irish Volunteers really intended to fight, he was taken aback at the assurance that they did indeed. With the coming of Easter Week in 1916, the priest saw the truth of those words for himself.

Father Fahy was at home near Athenry when he heard of the Volunteers taking up arms, just as Mellows had promised. Eager to play his part, albeit in a spiritual capacity, Fahy visited the gathered men in Moyode Castle every day to hear their confessions. While doing so, he took the opportunity to talk with Father Feeney, who was accompanying the Volunteers as an impromptu chaplain.

Feeney had asked him to go to Galway City to find out the views of their Church superiors. While Fahy was not able to meet Bishop O’Dea, other priests assured him that His Grace fully approved of Feeney’s aid to the rebels.

It was while in Galway City that Father Fahy heard that the Volunteers had suddenly departed from the Castle in favour of the abandoned country house of Limepark. Joining Father O’Farrell, they cycled towards the new base to catch up with his martial congregation.[42]

The priests were taken to Limepark, where the officers heard what they had to say. Mellows was sitting on the floor, his back against the wall. He had fallen asleep and so missed Father Fahy breaking some startling news. “They had definite information that Dublin had given in and that the soldiers in Galway were aware of our movement and were marching to meet us,” Hynes described.[43]

Kelly, who was sitting on a windowsill and listening in, would recall much the same thing: “I heard one of the priests telling all the officers assembled about the surrender in Dublin.”[44]

In this, the two witnesses were either misremembering or the priests had been confused, for the Dublin rebels would not formally concede until later that day, on Saturday afternoon. Whatever the truth, the already tenuous situation for the Galway men suddenly felt desperate.

The only thing left for the Volunteers to do, Fahy urged, was to acknowledge the inevitable and disperse while they still could. Monahan stoutly insisted that they continue to resist. The others were not so sure. Unwilling to voice his own doubts, Hynes equivocated, saying that they should wake Mellows and hear what he had to say.

Hard Decisions

After Mellows had had Father Fahy repeat the latest developments to him, he apologised for having been asleep. But, he said, he had brought the men out to fight, not flee. Even if he was to disband them, what then? They would be shot down like rabbits without a chance to defend themselves.

As for him, he would hand over his command to whoever wanted it. He was going to catch up on three days’ worth of sleep until the British arrived, and then he would battle it out with them to the last.[45]

Listening to this, Hynes knew that Mellows meant every word. Father Fahy tried a different tack, suggesting that the rest of the Volunteers should have the chance to discuss their options. Mellows argued that this was not necessary, for he had already put the question of continued resistance to the men in Moyode Castle, and every one of them had agreed to persevere. Fahy pressed on, asking if the rest of the officers who were not present could be consulted. After some hesitation, Mellows gave in and agreed to this.

At the subsequent meeting, Father Fahy outlined the situation to the fourteen officers present. Mellows continued to hold that it would be better to fight it out as their lives were forfeit anyway, considering how the five RIC captives of theirs would be able to identify everyone. When asked about this, the prisoners agreed to give no such information upon release, a promise they were to uphold.

At the end, the officers voted to disband, the only dissenters being Mellows and the faithful Monahan. For an alternative, Monahan urged for the Volunteers to take to the open country and pursue guerrilla tactics, as suggested before, but nobody seemed to be listening at that particular point.

Departures

When Father Fahy asked for this to be relayed to the men, Mellows excused himself, unwilling to ask a single man to leave after bringing them this far. And so the priest took on the task instead when the men had assembled outside Limepark House. Galway had done well but since they now stood alone, he told them, there was no point in carrying on. Better for them to return to their homes quietly and prepare for another day.

“Mellows did not address the men,” Father Fahy later wrote. “He was very depressed; the news from Dublin had upset him greatly.”[46]

Despite his own low spirits, Mellows did his best to console the others, many of whom were weeping openly. Those who offered to stay with Mellows were turned down. Things would blow over, he assured them. When one man noticed how Mellows lacked a coat and offered his own, Mellows accepted it only with reluctance.

Hynes was among the last Mellows approached to say farewell. Hynes told him he was staying with him, inwardly hoping the other man would not order him away like he had done with the others.

Instead, Mellows took his hand between both of his and said: “God bless you.”

Soon, the only ones remaining were Mellows, Hynes and Monahan. They were about to re-enter the old house when Mellows announced that it would be preferable to make a running fight of it rather than remain inside to be cornered. The other two agreed, as they probably would have to anything their leader suggested, and so the three of them set out together, towards an uncertain future.[47]

To be continued in: Rebel Runaway: Liam Mellows in the Aftermath of the Easter Rising, 1916 (Part III)

References

[1] Martin, Eamon (BMH / WS 591) p. 18

[2] Fogarty, Michael (BMH / WS 673), pp. 5-6

[3] Hynes, Frank (BMH / WS 446), pp. 10-11

[4] Monahan, Alf (BMH / WS 298), pp. 13-16

[5] Hynes, p. 11

[6] Workers’ Republic, 22/04/1916

[7] Fahy, Anna (BMH / WS 202), p. 2

[8] Ceann, Áine (BMH / WS 264), pp. 20-1

[9] Brennan-Whitmore, W.J. Dublin Burning: The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2013), pp. 22-4

[10] Malone, Tomas (BMH / WS 845), pp. 6, 8

[11] Malone, Bridget (BMH / WS 617), p. 3

[12] Manning, Michael (BMH / WS 1164), pp. 3-7

[13] Malone, Bridget, pp. 3-4, 8

[14] Newell, Martin (BMH / WS 1562), pp. 8-9

[15] Garvey, Laurence (BMH / WS 1062), p. 5

[16] Hynes, pp. 11-13

[17] Monahan, pp. 16-17

[18] Hynes, p. 13

[19] Newell, pp. 8-9

[20] Callanan, Patrick (BMH / WS 347), p. 8

[21] Kelly, Michael (BMH / WS 2875), pp. 5-6

[22] Newell, pp. 9-10

[23] Malone, Bridget, p.5

[24] Newell, pp. 10-11

[25] Kelly, pp. 6-7

[26] Connacht Tribune, 29/04/1916

[27] Ibid ; Kelly, pp. 7-8 ; Newell, p. 8

[28] Kelly, p. 8

[29] Callanan, pp. 9-10 ; CT, 29/04/1916

[30] Hynes, pp. 13-14

[31] Monahan, pp. 17, 19

[32] Malone, Bridget, pp. 5-6

[33] Callanan, p. 10

[34] Hynes, p. 14 ; Monahan, p. 21 ; Kelly, p. 8

[35] Jordan, Stephen (BMH / WS 346), p. 6

[36] Ibid, p. 7

[37] Monahan, pp. 21-22

[38] Hynes, pp. 14-15 ; Kelly, p. 9

[39] Hynes, p. 15 ; CT, 29/04/1916

[40] Hynes, p. 15

[41] Kelly, p. 10

[42] Fahy, Thomas (BMH / WS 383), pp. 2-3

[43] Hynes, pp. 15-6

[44] Kelly, pp. 10-1

[45] Hynes, Thomas, p. 16

[46] Fahy, pp. 4-5 ; Monahan, pp. 24-5 ; Kelly, p. 11

[47] Hynes, p. 17 ; Barrett, James (BMH / WS 343), p. 5

Bibliography

Book

Brennan-Whitmore, W.J. Dublin Burning: The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2013)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Barrett, James, WS 343

Callanan, Patrick, WS 347

Ceannt, Áine, WS 264

Fahy, Anna, WS 202

Fahy, Thomas, WS 383

Fogarty, Michael, WS 673

Garvey, Laurence, WS 1062

Hynes, Frank, WS 446

Jordan, Stephen, WS 346

Kelly, Michael, WS 2875

Malone, Tomas, WS 845

Manning, Michael, WS 1164

Martin, Eamon, WS 591

Monahan, Alf, WS 298

Newell, Martin, WS 1562

Newspapers

Connacht Tribune