A continuation of: Shadows and Substance: Seán Mac Eoin and the Slide into Civil War, 1922

The Beginning

Sligo burned…or, at least, that was the idea.

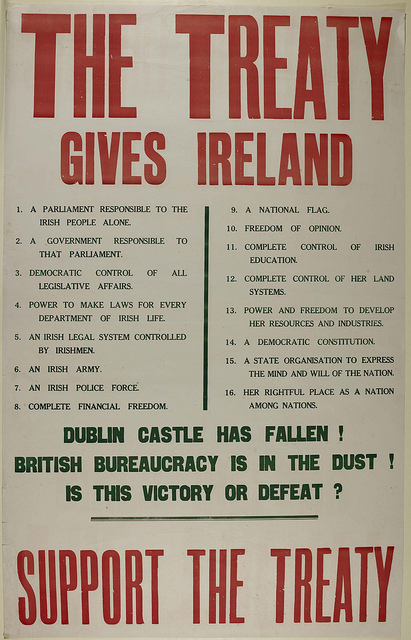

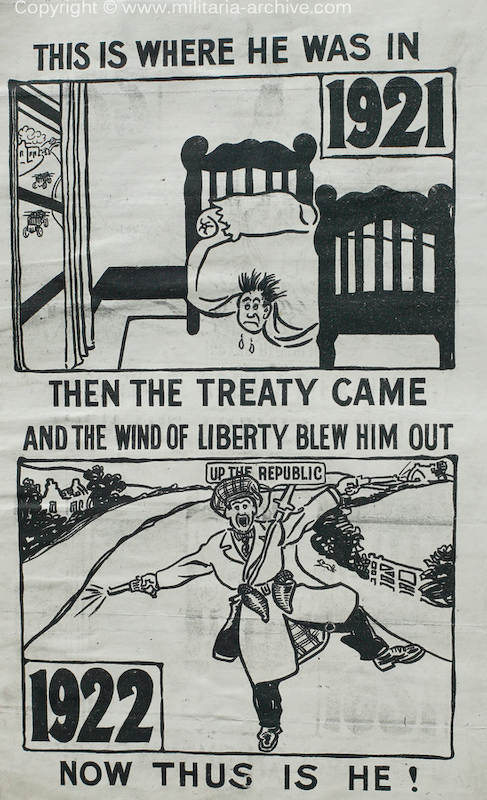

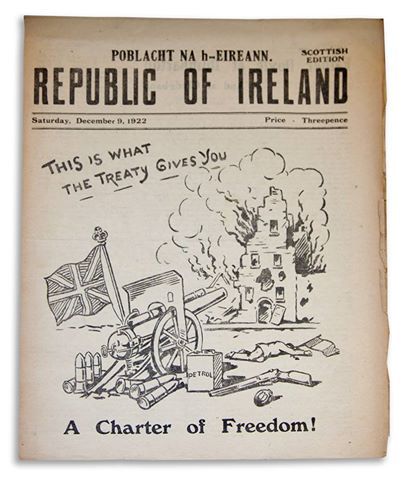

Since early in 1922, like many other towns in Ireland, it had played host to two armed and hostile factions, each claiming the mantle of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). One supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty and by extension the Free State born from that agreement, with the other adamantly opposed to both. It was an impossible situation, one that could not last indefinitely, as proved in June 1922, when simmering passions finally boiled over into outright violence in Dublin.

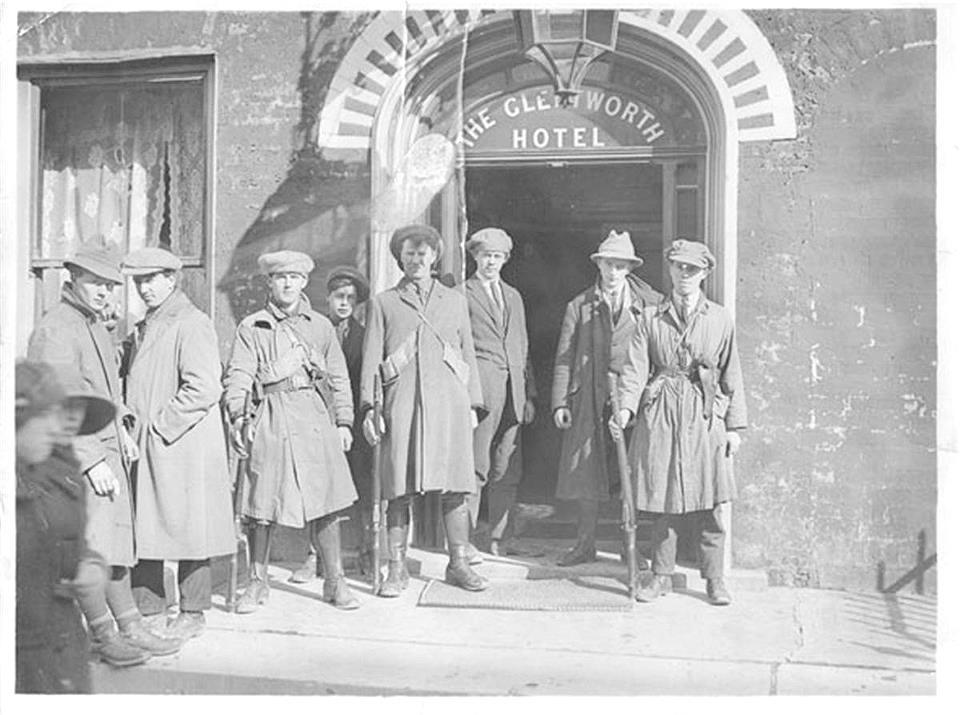

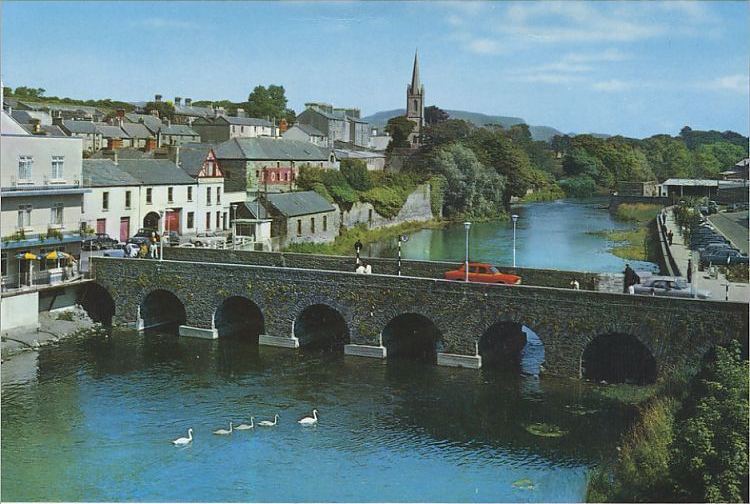

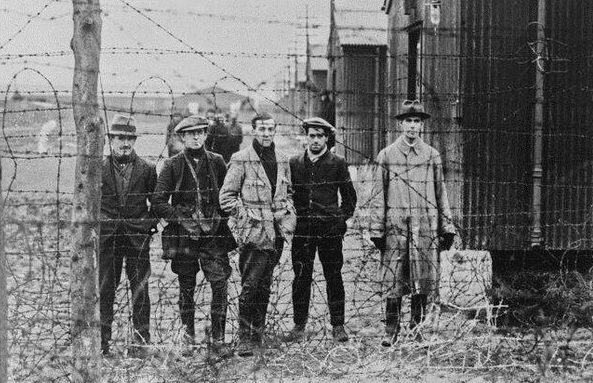

Sligo took its time in following the capital’s example. The pro-Treaty IRA, already in possession of the Sligo Prison and Courthouse, moved to commandeer a garage on the 28th June, placing themselves directly opposite their anti-Treaty counterparts in the Police Barracks, over which a flag emblazoned with the words I.R. Rebels, 1916 fluttered. Both parties then busied themselves in fortifying their claimed strongholds, such as in the coils of barbed wire looped outside the courthouse, while several families on that street hurriedly left their homes to stay with friends in other parts of town that would hopefully be less in the firing line.

Two days passed and each side had yet to make a move. Though menace hung heavily in the air, there were people, reported the Sligo Independent, who could not help but be drawn by the novelty of being in the middle of a not-yet-warzone:

From about 7:30 pm in the evening crowds began to gather in the vicinity of the Courthouse and Barracks to watch operations and remained until almost midnight. The tension was even greater than the previous evening, and it was commonly reported that the [anti-Treaty] Executive Forces had got a few hours’ notice to leave the barracks.

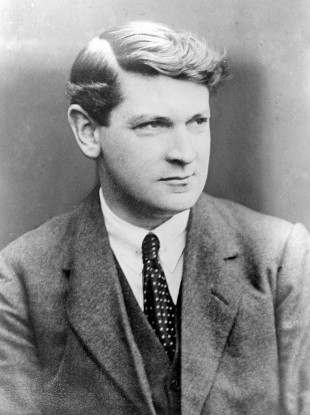

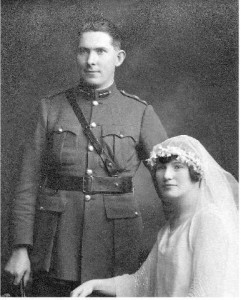

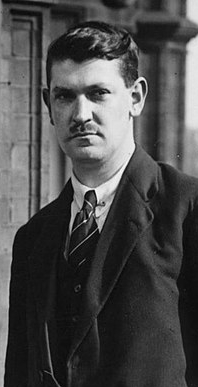

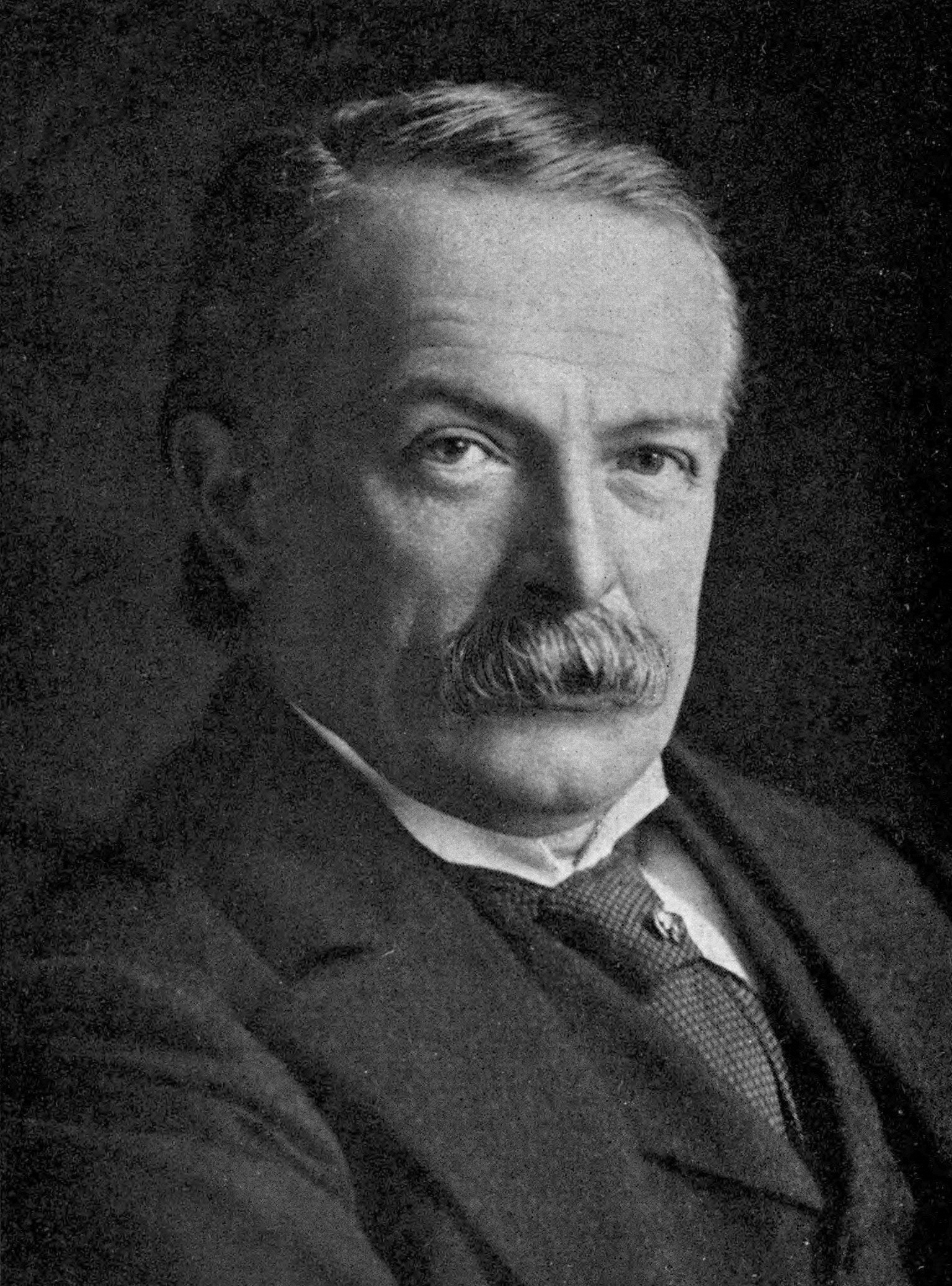

That the Anti-Treatyites did the following morning, the same day that Major-General Seán Mac Eoin returned to take charge of the pro-Treaty forces in Sligo. He had been on honeymoon in neighbouring Donegal when news of the outbreak in Dublin came through, recalling him to his command post. Mac Eoin arrived in time to find the Police Barracks ablaze, its anti-Treaty garrison having pulled out in the early hours of the morning before torching it and the adjoining Recreation Hall in a ‘scorched earth’ tactic. Civilians who tried to reach the Town Hall where the firehose was kept were turned back at gunpoint by those same arsonists.

Mac Eoin was not so easily deterred. He marched to the Town Hall, a squad of his soldiers in tow, and came back with the firehose in hand. Seeing that the Barracks and Recreation Hall, both burning fiercely, were beyond help, Mac Eoin instead turned the water on their surroundings.

It took three hours for the Barracks to burn, during which a number of bombs carelessly left behind were heard exploding. By the time the flames died down, the two buildings were ruined shells, but the rest of Sligo was safe, from the fire at least. Mac Eoin, along with some local men, earned praise from the Sligo Independent “for their fearless work” in firefighting.[1]

Opening Moves

There just remained the other kind of fighting to be done, of which much was promised. After all, the Anti-Treatyites had only quit one base and not the war, withdrawing instead to either the countryside or to Sligo Military Barracks in the appropriately named Barrack Street. Despite the arson and the drama, blood had yet to be spilled, unlike in Dublin, although Sligo could hardly be described as peaceful either.

Determined to maintain the initiative, Mac Eoin stationed his soldiers around the town, where they stopped and searched a number of motorcars, and detained in the Courthouse a number of youths known to hold Republican views, although most of these were soon released. When a Ford van carrying three men drove from the Military Barracks to a garage in Bridge Street, Mac Eoin rushed to the scene. The vehicle occupants were demanding free fuel from the garage owner when Mac Eoin arrived to hold them up with a revolver until his subordinates came to remove the three miscreants to the prison.

The streets were by then occupied only by armed men from either faction, all civilians having the sense this time to remain indoors. The Anti-Treatyites did not remain in the Military Barracks for long, evacuating it on the midnight of the 30th June. As with the Police Barracks, they left nothing for the opposition, having sprinkled the interior with petrol before setting it alight. The fires ate hungrily until only bare walls were left standing amidst smoking ashes.

The Anti-Treatyites, said to be numbering several hundred, next moved to the Drumcliffe district, leaving their opponents to patrol the streets of Sligo. Several arrests were made, including one by Mac Eoin personally, according to the Sligo Independent:

At about 6 o’clock in the evening, a Republican policeman named Jack Pilkington, of Abbey Street (brother of Com.Gen. [Liam] Pilkington, Irregular forces) was arrested by Major-General McKeon in Bridge Street, and it is alleged that some ammunition was found in his possession. He was conveyed to the Jail, but was released in a couple of hours time.[2]

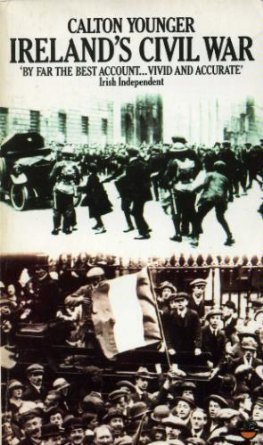

Others who had likewise been picked up continued to be detained, so it seems that Jack Pilkington was not taken to be a great threat. A more dramatic depiction of the encounter between him and Mac Eoin was narrated years later by Calton Younger, in which Mac Eoin, in fact, had had a narrow escape. As Younger profusely thanked Mac Eoin in his acknowledgements, it can be assumed that it was he who relayed to the historian how he had been standing by while Sergeant Ingram did his best in starting the engine of their recalcitrant motorcar. As the nub of the conflict had shifted out of Sligo, the town seemed secure enough for the Major-General to take his leave and head eastwards to Athlone, where his responsibilities as GOC (General Officer Commanding) Western Division awaited.[3]

But Sligo still had a surprise to offer, when a shriek from a woman to his right alerted Mac Eoin to Pilkington sneaking up on him with his revolver aimed. Pilkington – referred to by Younger only as “a young man, a brother of a Republican leader” – had time to squeeze off a shot, the bullet grazing the forehead of his quarry, before the other man sprang at him. Mac Eoin heard the click of the revolver’s hammer as Pilkington attempted a second time but either the gun was empty or jammed – and then Mac Eoin was on his would-be assassin, seizing first the revolver, which he threw to the ground, and then the two grenades Pilkington had on him.

A strong man, as befitting a former blacksmith, Mac Eoin took Pilkington by the scruff of the neck in one hand and his trousers’ seat in the other, and tossed him into the river. And that was that. Sergeant Ingram finally got the car going, and Mac Eoin climbed on board, along with his bride, Alice, Captain Louis Connolly and the Rev. Patrick Higgins of Ballintogher. With Ingram at the wheel, the party began the drive to Athlone.

Whichever version of events is more plausible – the Sligo Independent’s or Younger’s – is a question left to the reader.

Road Trip

The car had only made two miles out of Sligo before becoming the target of shots in a roadside ambush. Mac Eoin and Captain Connolly leapt out, pistols drawn, an act more daring than prudent – after all, driving on out of harm’s reach would have been the safer option. Incredibly, this display was enough for a cease-and-desist order to be called from amongst the ambushers, either due to Mac Eoin being recognised or, as speculated by Younger, because a woman was seen to be in the car.

Exerting the same ‘take charge’ attitude shown in Sligo, Mac Eoin called the enemy officer over, followed with another demand, this time to surrender, which Gilmartin – as named in Younger’s book – obligingly did. With this easy victory, Mac Eoin let Gilmartin and his men go. No harm, no foul, after all, and, besides, he probably did not have space in his car for prisoners.

Similarly submissive were the three passengers in another car encountered further on. They claimed to be in the same army as Mac Eoin, as supported by their green uniforms, but when an unyielding Mac Eoin told them, all the same, he could not leave soldiers of his to their own devices, the trio confessed that they were Anti-Treatyites. Mac Eoin ordered them out of their car and to surrender their guns, which they did meekly. They were equally acquiescent when Mac Eoin next told them to get back onboard, turn their motorcar around and drive ahead of his own.

A road-block was next. When Mac Eoin instructed his commandeered advance guard to clear it, the other men uncharacteristically refused. Suspecting that this was more due to fear than defiance, a hint at the possibility that the barrier was mined, Mac Eoin decided to go back the way he had come and chance another route, after first disabling the other vehicle and leaving the trio stranded.

As the party of four neared Athlone, more obstacles appeared, this time in the form of tree-trunks laid across the road at Glassan. Whoever responsible had been careless enough to leave their bicycles – about twenty, in number – propped up against a wall. Mac Eoin was about to wreck them until Alice urged her husband against further delays. Since it was already past midnight, Mac Eoin drove to a nearby friend’s house to spend the night. In the morning, he issued word to a unit of his in Ballymahon to remove the offending trunks.

“There he learned how much he owed to his wife’s fatigue, or perhaps to her intuition, the previous night,” explained Younger:

The bicycles belonged not to the Republicans who had felled the trees but to a party of his own troops who had begun to clear the road and who had taken cover when McEoin’s [alternative spelling] car approached. Had McEoin begun to break up the bicycles, the clearing party, uncertain of the identity of the people in the car, would have taken them for Republicans. McEoin would have found himself ambushed by his own men.

Compounding the dramatic irony and tragic potential, narrowly unrealised, was how the Pro-Treatyites had been led by Mac Eoin’s brother. The fratricide of the Civil War had almost become literal.[4]

Holding Out

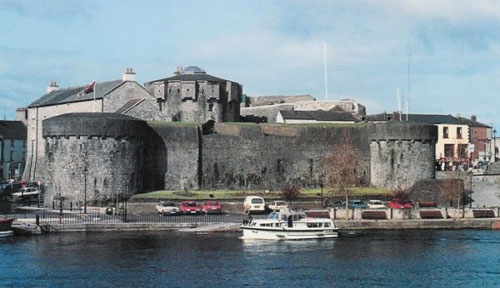

In Athlone, Mac Eoin found an island of relative calm amidst the chaos, the town having “been immune so far from the horrors of the conflict,” according to the Westmeath Independent. The newspaper attributed this privileged state:

…to the precautions taken by the troops stationed at the Custume and Adamson Castle Barracks. Soldiers from those barracks are mounted on guards on all the local bridges, and on the roads verging on the town, night and day. Pedestrians after a certain hour at night are challenged and questioned. Provided their answers are satisfactory they are allowed to pass on. All motorists are held up, their cars searched, and the occupants questioned.

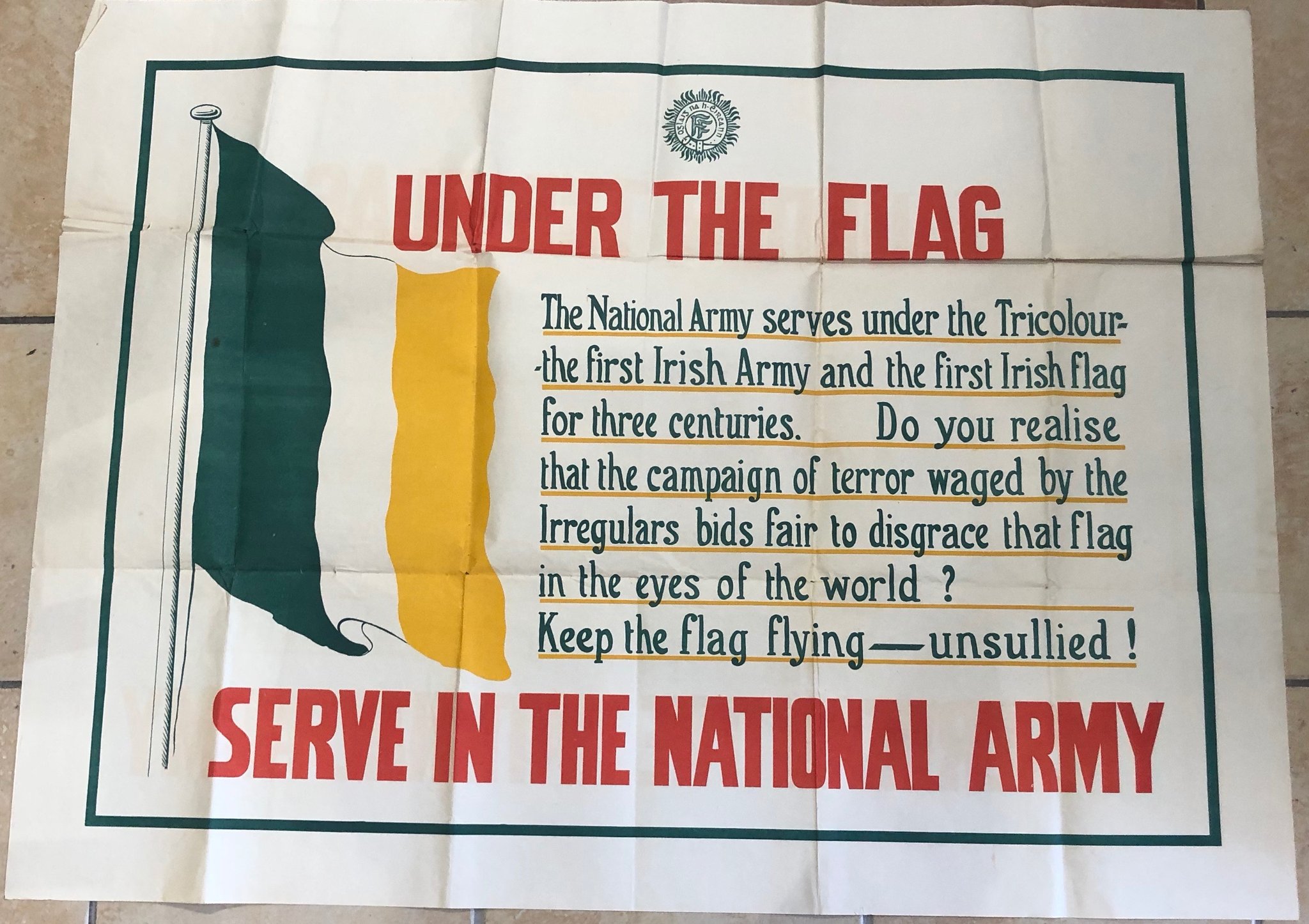

Athlone had also benefitted from not having to share itself with more than one army at the start, unlike Sligo. Outside the town was a very different scenario, however. On the 5th July, the day after Mac Eoin reached Athlone, a pro-Treaty patrol – from the newly christened ‘National Army’ – was moving between Moate and Ferbane in a Lancia car and a Ford when they were fired upon. By the time the troops fended off their assailants, 20-year old John Blaney had been shot in the head and slain.

As a local man, whose family lived on Wolfe Tone Terrace, his death was keenly felt by many:

The sad scenes witnessed at the bier in the morgue…were most affecting. The bereaved father, brothers, sisters, relatives and friends gathered round with tear-dimmed eyes, mourning the loss of their affectionate son and brother. With them the utmost sympathy is felt by the citizens of Athlone, irrespective of creed or class, in the terrible affliction.

That was not to be the only skirmish that day. Later in the evening, people were alarmed when a lorry hurtled into Athlone on three wheels, the fourth having been punctured, and with its engine close to overheating. When it reached Custume Barracks, the driver and his passenger, both covered in blood, practically fell out and had to be taken at once to the military hospital. The news they brought back was urgent: their ten-man squad had left Longford for Athlone when an ambush stopped them at Tang.

While the other eight stayed behind, Harry McDermott, wounded in the face and hands, and Campbell, bleeding from a bullet to the abdomen – their ages being nineteen and eighteen respectively – drove the lorry at punishing speed to Athlone for reinforcements. By the time these arrived on the scene at Tang, Brigadier-General Dinnegan had also been severely wounded. One week into the war and the casualties were rising, bit by steady bit.

The Soldier’s Song

Those who thought that the day had seen enough drama were proven wrong when the crack of rifles and machine-gun rattles were heard from the direction of Cornamaddy at 7:30 pm, loud enough to rouse a relief force from Custume Barracks, led by Mac Eoin in his motorcar:

To all appearances a big battle was in progress, and rumours were current as to heavy casualties. The firing continued to range in intensity for half an hour. Crowds of people assembled along the side-walks from the Ballymahon Road to Custume Barracks, awaiting news from the seat of war.

Contrary to rumour, no losses had been suffered by the time the troops returned to Athlone, jubilantly singing The Soldier’s Song through the streets, with the cheers of onlookers as a chorus. Despite this triumphalism, the facts remained that the IRA – that name permitted to the Anti-Treatyites at least – had been bold enough to spring another attack – on a Red Cross lorry and a military truck at a crossroads in Cornamaddy – and escape without harm, despite searches in the nearby woods and bog by the National Army. Athlone was seeming less like an oasis of peace and more as a besieged fortress, its populace hemmed in and the rest of the area vulnerable.

“People living in the outlying districts are in a state of terror only equalled by that experienced during the Black-and-Tan regime,” reported the Westmeath Independent, one of the few sources of information at hand for an area otherwise cut off from the media:

We are reliably informed that parties of armed men visit the farmhouses nightly and take out the young men at the point of the rifle or revolver and force them to fell trees and trench the roads.[5]

Whether Athlone or elsewhere, “the Free State were very frightened of us,” remembered Michael Kilroy, the commander of the Mayo IRA. Once his troops had swept the opposition out of Mayo – an easy enough feat to perform, he was sure – Kilroy would lead them on to Athlone, where “I heard that MacEoin was boasting how impregnable his barracks was there. Petrol in cans up a ladder would take it, we thought.”[6]

Perhaps it is little wonder then, as Con Moloney surveyed the national picture from the current IRA headquarters in Limerick, the Adjutant-General of the anti-Treaty forces did not rate Mac Eoin’s position a strong one. “We expect to capture a few small posts in his area within the next week. We will keep him busy in any event,” Moloney wrote in a report on the 9th July. He went so far as to speculate on how committed the enemy general really was to the contest: “It is possible that we may be able to keep McKeown [alternative spelling] neutral. In any case he is now entirely on the defensive.”[7]

High Expectations

In defence of Kilroy’s and Moloney’s retrospectively hubristic assessments, from where they stood, the war was all but won. Counties in the Irish North-East “are practically in our hands,” according to Moloney, “except for a few posts in the Roscommon area and McKeown’s troops in Sligo.” The National Army was not doing much better in the Third Southern Division (Offaly, Laois and North Tipperary) either, where:

We occupy Birr Barracks and another two posts. McKeown advanced on one of these posts, but was forced to return again to Athlone. F.S. [Free State] forces in his area are cut off from each other by Road, Rail and Wire and will not be able to attack here until Kilkenny and Thurles are removed.

With much of Munster also in Republican hands, “generally speaking, we are having the best of the matter, and things are settling down to real business. I expect we will control say from the Shannon to Carlow in a day or two.”[8]

The Anti-Treatyites were confident enough to attempt an assassination on Mac Eoin – if not neutral, he could at least be dead. Some IRA officers in Mayo who had sided with the Treaty were held prisoner in a house, with the expectation that Mac Eoin would come to their aid. Preparations were made for his arrival by the ambush team, who mined the road and took up position in a wood opposite a rocky peak of slate that would hopefully ricochet their bullets back into the kill-zone.[9]

Which was all for naught as Mac Eoin never appeared and alive he remained. In a quirk of fate, one of the ambushers-to-be, Broddie Malone, was later a captive in Custume Barracks in Athlone, supervised by the man Malone had targeted. If Mac Eoin knew, then there were no hard feelings, for, according to Malone, “MacEoin was decent to me and to the men.”[10]

But that lay in the future. Writing on the 13th July, four days after his first optimistic analysis, Moloney announced more good news for the IRA and bad progress on Mac Eoin’s part: “Athlone attempted to march on one of our posts in 3rd Southern area, but were forced to return again to base.”[11]

Speaking to Younger, Mac Eoin made no mention of either of these two setbacks in the Third Southern areas. He did, on the other hand, lament a failed attempt on IRA-held Collooney, Co. Sligo, as initially reported by the Irish Times:

On Monday evening [10th July] a strong force of National troops arrived in Sligo and subsequently left for the Collooney area. Firing began at about 11 o’clock, and continued until the late hour on Tuesday morning. It is anticipated that the next few days will see the end of the struggle.[12]

As it turned out, the engagement did not last the second day, as the Pro-Treatyites fell back prematurely, seemingly due to a confusion over orders – assuming it was an honest mistake and not a dishonest one as Mac Eoin suspected: “Whether it was the typists who carried out the operation orders, or who it was, I don’t know.” Though not present, Mac Eoin darkly hinted to Younger that the reason for the defeat was not so much the opposition without as the traitor within: “At this stage, some of our forces and some of our staff were not loyal.”

Mac Eoin, Younger noted, “seems glad that he does not know who among those he trusted let him down.”[13]

Regardless, the anti-Treaty stronghold in Collooney remained a nut in need of cracking. If treachery had indeed been the cause of the initial failure, then Mac Eoin avoided a repeat by the ruse of taking his one hundred and twenty soldiers on the evening train from Athlone to Dublin, ostensibly for training, and then switching at Mullingar for the line to Longford, Boyle and finally Sligo town. By 6 o’clock on the morning of Saturday, the 15th July, they had reached the outskirts of Collooney, meeting up with an allied detachment under Colonel Anthony Lawlor.

Lawlor’s men covered the northern road into Collooney, while Mac Eoin took charge of the south side. The Major-General sent two messages: the first to the town’s Catholic priest and Protestant minister to lead their congregations to safety, and then an ultimatum to the enemy garrison, calling on them to surrender. When a volley of shots gave a wordless answer, the battle for Collooney was on.[14]

The Battle of Collooney

MUTINEERS’ BRIEF STAND

The following official bulletin was issued by G.H.Q., Irish Army, at 3:45 pm on Saturday [15th July 1922]:

“Collooney, a stronghold of the Irregulars in the West, has been taken by our troops, after four hours’ fighting. Seventy prisoners, with arms and ammunition and a store of explosives, were captured.”

Our Boyle Correspondent says that the National troops, who were commanded by Major-General McKeon, were equipped with machine guns and artillery. The Irregulars at Collooney numbered about 400, and they put up a strong resistance. Four snipers in the tower of the Protestant church kept up the firing until the shells from an 18-pounder made the position untenable.[15]

(Irish Times, 17th July 1922)

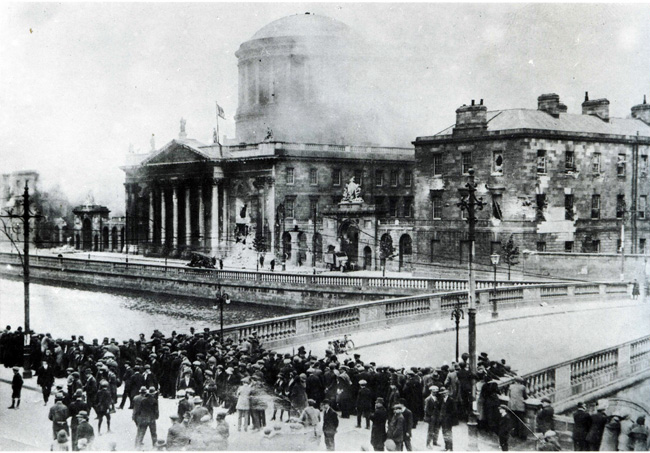

Things did not go quite so smoothly as this article might suggest, and Mac Eoin was to describe to Younger a much more rough-and-tumble affair. The aforementioned 18-pounder, which had seen action less than a month earlier against the Four Courts in Dublin, was positioned in a sawmill when the enemy machine-gun nest in the church tower identified it as an immediate target. A bullet scored a groove over the scalp of a surprised Sergeant Kenagh, narrowly avoiding worse.

As Kenagh ducked behind the shield of his artillery piece and scanned the surroundings for the perpetrators, Mac Eoin:

…showed him and [Kenagh] levelled the gun at the tower. The first shell went straight through a window in the belfry and exploded. Every bell rang and the whole of the top of the tower was blown up into the air, sandbags, machine-guns, Irregulars and all, and it landed and got jammed in its usual place as if nothing had happened.

Colonel Lawlor tried to follow up this stroke of good shooting with a bayonet-charge on the IRA position – except that none of his soldiers would do so. It was left to Mac Eoin to lead the assault by his own ‘men’ – to use the term loosely as none were over eighteen years of age – jumping over the church wall and into the graveyard, to find “sixteen fellows, with rifles and all, lying on the flat of their backs. Not only did they put their hands up, but they put their feet up too,” Mac Eoin triumphantly told to Younger.

A Soldier and Statesman

The prisoners were moved to the rear, and the push into Collooney resumed. As before, as he had always done, Mac Eoin led from the front – no Douglas Haig, he – even if such boldness almost came at a fatal price:

I was standing at a hall door when a machine-gun opened up on me and it cut the track of myself in the hall door and cut my tunic and coat to ribbons. A young soldier from Killaloe saw where the machine-gun was placed and he jumped out into the street, went down on one knee and fired, wounding the gunner.

The struggle took the better part of the day, with shots continuing to be heard throughout the night, but the town was officially Mac Eoin’s by morning when the anti-Treaty commander, Frank O’Beirne, and twenty-two of his subordinates surrendered in a house by the train station. Also in Mac Eoin’s possession, and equally appreciated, were a number of salmon that had been left to boil in a huge iron pot:

During the fighting the fire had gone out and the water had already boiled away. And here the salmon was – beautifully cooked and still piping hot – enough for us all and the sweetest meal I ever touched in my life.[16]

Collooney was added to the tally of Free State gains elsewhere in Ireland that week: Dundalk and a fort on Inch Island, Lough Suilly, Co. Donegal, as part of a determined drive by the beleaguered Pro-Treatyites to regain the initiative. But neither of the others impressed the Special Correspondent of the Irish Times as much as the Sligo win: “Except in the West, where General McKeon has won a distinct and important victory at Collooney, there has been no engagement which ranks above the dignity of a skirmish.”[17]

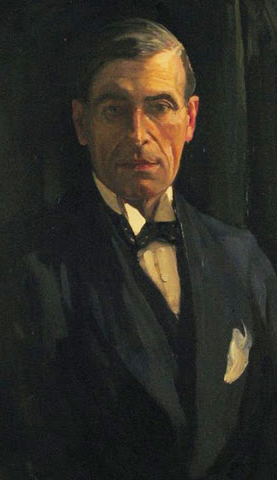

Republican dispatches speculated no further about Mac Eoin’s dedication. Returning to Athlone, he was, in addition to being feted as a conquering hero, presented with a bank draft of £279 by Father Crowe on behalf of the townspeople. It was an overdue wedding present, explained the padre, but also a mark of appreciation from those who:

…regard you not only as a great soldier, but as a great statesman and a man with a clear political outlook; one who is prepared to be the protector of the people, and who has urged that the army should be the guardians and not the dictators of the civil population.[18]

A cult of personality had its benefits in regard to morale. “To flatter you a little sir, but it is the truth, the boys are saying ‘Up McKeon and into it,” so Mac Eoin was informed by Lawlor in a dispatch from the Claremorris warzone in November 1922. “By-the-way the hospital is called ‘Hospital McKeon.’”[19]

While taking Lawlor’s self-confessed brownnosing into account, Mac Eoin’s enemies also acknowledged this adulation, even if they had cause to resent it. Arrested by the Free State, Michael O’Donoghue was taken to Longford town for detention in its barracks. As it was fair day, there were large crowds of people about, some of whom noticed the anti-Treaty POW being marched through their midst. O’Donoghue found himself surrounded by the sticks and cudgels of a jeering, inebriated mob, much to his terror.

While taking Lawlor’s self-confessed brownnosing into account, Mac Eoin’s enemies also acknowledged this adulation, even if they had cause to resent it. Arrested by the Free State, Michael O’Donoghue was taken to Longford town for detention in its barracks. As it was fair day, there were large crowds of people about, some of whom noticed the anti-Treaty POW being marched through their midst. O’Donoghue found himself surrounded by the sticks and cudgels of a jeering, inebriated mob, much to his terror.

“Sean McKeon, the local hero, had gone Free State and, being the military idol of the midlands, anyone hostile to him, that is any “Irregular”, was regarded as anathema,” O’Donoghue explained in his reminiscences, a touch sourly.[20]

Taking Stock

Despite all the bullets spent in Collooney, no fatalities were inflicted on either side but, of injuries, there were plenty, some of whom were taken to Athlone Military Hospital. Convalescents included a man caught in an accidental explosion in Sligo, suffering wounds to the face as well as his hands, both of which had been amputated, though at least his eyesight – previously feared lost – was recovering. The brush with death by another soldier, from when a bullet struck beneath his heart, merited Mac Eoin’s bedside congratulations.

Such gestures did not go unappreciated. A visiting journalist who accompanied Mac Eoin noticed how:

The General, who visits all his wounded soldiers each day, displayed a fatherly interest in their condition. He chatted freely and gaily with the patients, whose faces lit up with smiles at his approach.[21]

A more sombre paying of respects was in Longford, where Mac Eoin attended the funeral of Lieutenant Patrick Callaghan, killed in an earlier engagement near Collooney. Callaghan had served under Mac Eoin as part of their IRA Flying Column, taking part in clashes against British forces at Granard and Ballinalee in November 1920, as well as the capture of the Arva and Ballymahon police barracks.[22]

“Commandant Callaghan is said to have been Major-General McKeon’s right hand man in his mobile column,” noted the Sligo Independent, “and was carrying a revolver and holster which had belonged to one of the Black-and-Tans.”[23]

The suggestion that Callaghan had been in command at the time of his death, and thus in a way responsible for it, was enough for Mac Eoin to write to his Chief of Staff, Richard Mulcahy, on the 26th July 1922, full of outrage on the deceased’s behalf:

I knew Callaghan RIP and the statement contained in the letter in question was a deliberate lie. He was not in charge of the men, as the O/C of the Division was there and most likely he was in charge. Even if Callaghan was in charge it would not be his first time to be in charge in an ambush and come out successfully.

The author of this offending rumour was unknown, though Mac Eoin guessed it was “one of those who envy the success of the National Troops and is doing his best to cause disturbance by circulating infamously slanderous information.” Another record defended was Mac Eoin’s own, which suggested that not all of the news coming into the capital from the West was complimentary. “I am not going into the question but believe me that there is no laxity of descipline [sic] among the troops in my command,” he told Mulcahy tartly.[24]

Even Michael Collins was not spared his pen. The pair had been the best of friends during the prior conflict: when Mac Eoin was caught by the British authorities and sentenced to death, Collins had spared no effort in his rescue. Civil war had sundered old relationships and now it was putting even the remainder under pressure.

“These bills have been accruing for months and you may remember when you were here last they were giving me considerable trouble and there has been no improvement since,” Mac Eoin wrote to Collins, now his Commander-in-Chief, on the 22nd August 1922. Custume Barracks had debts waiting to be honoured since March, and Mac Eoin, public darling he may have been, was not naïve enough to think that the vendors of Athlone could be kept waiting indefinitely. “These will require an immediate improvement or we will be in as bad favour with the people as the Irregulars – perhaps worse.”[25]

‘A Ladder of Rifles’

As Collins was shot and killed in an ambush the same day, he might have already been dead by the time Mac Eoin sent his complaint to him. However strained their last communications to each other, Mac Eoin attended the funeral, walking behind the tricoloured-draped coffin at the heart of the procession through Dublin. “Big, forceful, and prematurely grey,” was how one reporter described him. Also showing the weight of grief and war was Mulcahy, who had big shoes to fill as the new Commander-in-Chief, “a frail figure, with drawn, tense features and downcast gaze.”[26]

But affairs of state wait for no man, and both Mac Eoin and Mulcahy had plenty to attend to, civilian as well as military, in the opening of the Provisional Parliament on the 9th September, in Leinster House, Dublin. The two generals forewent their uniforms, Mulcahy appearing in “his old brown homespun”, according to a journalistic eyewitness, while a plain-garbed Mac Eoin “looked as if he had just stepped out of Conduit street.” After the start of the session, there was little else to be done or said, save the constant interjections by Laurence Ginnell, the one anti-Treaty representative present, as well as the only attendee who refused to sign the rolls. Instead, the TD for Longford-Westmeath repeatedly and loudly demanded to know if the assembly before him was truly Dáil Éireann or a partition parliament.[27]

Ginnell was finally ejected. Not many seemed sad to see him go, with “Sean MacEoin being the only Free Stater to get up and shake hands with him before he was put out,” recalled his wife, Alice Ginnell.[28]

Mac Eoin was not quite so magnanimous later that month in the Dáil, on the 28th September. Dr Patrick McCartan, the TD for Monaghan, moved for an immediate truce in the war, to last no less than fourteen days. With the choice before the Government now to either negotiate with the enemy or exterminate them, McCartan believed that peace should be given one more chance. Give the irregulars a ladder to climb down on, he urged.

McCartan’s proposal attracted some support in the chamber but also opposition, notably from Mac Eoin who, having just returned after two weeks of hard campaigning on the other side of the country, was in a no-nonsense mood. No one in Ireland was no more inclined than he towards such a ladder, he told the Dáil, if he thought it would accomplish anything. But a similar offer had recently been made to him for three days of ceasefire in the West, except this pause in the fighting was intended on the part of the Anti-Treatyites to allow a shipment of arms to reach Sligo. Had that gunrunning attempt succeeded, then the irregulars would have been in a position to not so much negotiate terms as dictate them. That would be their ladder.

“A ladder of rifles,” interjected Denis J. Gorey, the TD for Carlow-Kilkenny.

‘All the devilments imaginable’

Mac Eoin had been equally hard-nosed earlier that day in the Dáil, this time as part of the debate over the establishment of Military Courts for war prisoners, with the powers to impose terms of penal servitude…or even the death penalty. Amendments to have detainees treated as POWs, with the rights and recognition that came with this status, or to have the courts chaired by legal professionals, were defeated by the Government representatives, who were determined not to allow even beaten subversives an extra inch.

Putting Military Courts under civilian oversight would be giving authority with one hand and withdrawing it in the next, Mac Eoin warned. Practically curling his lip as he addressed the chamber:

Personally speaking, he did not think that there was necessity for any legal advisor – (laughter) – because all the legal advisors he knew they could compare with some of the members of the House – (laughter) – they play acted with words and phrases, and were up to all the devilments imaginable. (laughter). When they came down to hard realities, there was not one gram of common sense in all their knowledge.

In contrast:

An army officer quite appreciated the position of those who fought in arms against him. Although he had been in arms against the officer, yet they were of the same way of thinking, and the officer appreciated the position and would act justly and could have sympathy with, and appreciation of, the man’s position. Such an officer should be made President of the Court, and not the legal advisor.

This lofty statement did not quite convince Thomas Johnson. The Labour Party leader voiced his doubts as to whether even Major-General Mac Eoin, a man Johnson praised as being second to none in ensuring the subordination of military authority to the civil one, would keep a cool head when deciding the fate of his enemies. Had Mac Eoin not publicly stated months ago, at the inquest into the slaying of George Adamson in Athlone in April 1922, that he would have shot dead the guilty party if he could?

“That is one of the things we want to try to guard against,” Johnson declared.

That was different, Mac Eoin replied. He did not deny voicing his intent to kill or the intent itself, only that there had been no other recourse at the time. Now there was, in the form of the Military Courts, the implication being that he would have no need to act illegally if he had the state to do so legally instead.[29]

And this was from the man previously lauded as a model of chivalry. The preceding fortnight had evidently done much to harden Mac Eoin but, then, nothing about it had been easy. Despite early wins in the first few months of the Civil War, the Free State remained in a position of weakness, or so it felt to Mac Eoin when reporting his woes to Mulcahy on the 4th September 1922.

The money shortages he had complained about to Collins had not abated, leading to his “men waiting for supplies which were promised for Friday last, but have not yet arrived.” Mutiny was increasingly a danger, to the extent that an outpost in Leitrim, “Dromahaire has been lost this morning – as far as I can learn handed over to the enemy.” The loyalty of National Army that Mac Eoin had defended before was no longer something even he could take for granted, leading him to urge Mulcahy to “do something about pay for Regulars at once.”[30]

Pressing Back the Forces of Disorder

If he was looking for sympathy, then Mac Eoin had turned to the wrong man. “I fear very much that you are being let down in your area,” Mulcahy wrote to Mac Eoin in a cutting but not untypical-for-him letter:

Personally, I cannot sense that there is any solid administration or organisation over the area pressing back the forces of disorder. I am afraid that I begin to find this, namely, that the people of the area feel that no impression at all is being made on the situation, and that they are beginning to whisper to themselves that they have no confidence in ‘Sean McKeon.’[31]

The main danger, as Mulcahy saw it, was that their troops were spread too thinly about their freshly won gains, sitting exposed in small bases and left “at the mercy of any small band of Irregulars with a ‘punch’ in them.” Instead, Mulcahy wanted these outliers pulled back, regrouped and retrained – his strategy for the next few weeks counted on it, as he instructed Mac Eoin: “You will understand that it is absolutely necessary to have at our disposal central force enough to allow elasticity in our plans.”[32]

The costs of this was the abandonment of civilians to the rapaciousness of hungry IRA bands and garden-variety criminals, the fear of which prompted a solicitor in Roscommon to urge Mac Eoin, on behalf of the great and the good of society, “the priests, bankers and the townspeople of Elphin”, not to remove his soldiers as planned. The response – “he was told that…they would have to stand up with a good show of civic spirit against any robbers” – was unlikely to have been overly reassuring.[33]

So Mac Eoin relayed to Mulcahy. The Major-General was evidently sympathetic to their plight, much to Mulcahy’s frustration at what he saw as his subordinate’s foot-dragging:

I am sorry that you allowed yourself to give in in any way on the point of your removal, because it opens the way for further representation when you come to move them now in a few days.

Delays would do no good, Mulcahy warned, for his mind was made up:

You must set yourself absolutely to have everything prepared for the systematic putting into operation of the scheme on and from 22nd [August]. I give into you as far as that date, in view of the fact that you probably have committed yourself to it, but we must go straight ahead with our own work immediately and there should be no further postponement.[34]

The pair would never enjoy a harmonious working relationship, but worked together they did all the same, enough, by early September, for Mac Eoin to have the manpower available for a renewed push in Sligo, which had remained contested despite his previous win at Collooney. This second wind came not a moment too soon, for the Anti-Treatyites were undertaking a surge of their own. Several Free State posts had been attacked, and though most held out, Ballina did not.

Mac Eoin dispatched Lawlor to retake the town, which the latter accomplished with minimal effort as the IRA occupiers had already abandoned their prize, in keeping with the hit-and-run tactics they favoured. Lawlor was presumably expecting a similarly easy time on his journey through the Ox Mountains to Tobercurry, where Mac Eoin was waiting with the rest of their army. If so, then it was a bad miscalculation.

“The road made a series of s-bends round low, bumpy hills. We had a number of vehicles and we couldn’t see more than one car’s length in front of us,” Lawlor recalled to Younger. “They ambushed us, got us badly. Colonel Joe Ring was with us, a great old fighter, and I said for him to take one side of the road and I’d take the other.”[35]

Taking Sligo

TROOPS AMBUSHED –

COMMANDER AND DRIVER KILLED

News reached Boyle on Thursday evening [14th September] that Commandant Ring and the driver of an armoured car have been killed in an ambush at Bonniconlon, on their way to Tobercurry, on Thursday morning by a big party of Irregulars. It is also reported (but not confirmed) that General Lawlor, commanding the troops in that area, is wounded…The death of Commandant Ring…is greatly regretted all over the country.

It was learned from official quarters last night that Major-General McKeon was not with the party of troops which was ambushed.[36]

(Irish Times, 16th September 1922)

Mac Eoin was present, however, to pass judgement on the ten Anti-Treatyites taken prisoner in the effort to fend off the ambush. After Lawlor and his surviving party made it to Tobercurry, they brought their catches to Mac Eoin, who “ordered a court-martial and they were sentenced to death, the whole lot,” according to Mac Eoin in Younger’s book.

That did not sit right with some in the town, either out of the personal connections with the condemned or general humanity. An appeal for clemency was made to Mac Eoin, much to his annoyance: “I told them they’d had none for Joe Ring and those fellows on the road, so it was hard for one to expect me to have it. Then I say, ‘Very well. Here they are for you. Take them yourselves and be accountable for them.’”

Mac Eoin may have been misremembering things somewhat, for the Military Courts had not yet been formed and, without them, he had no authority to sentence anyone to death. Not that he would have carried out the penalty anyway, for, as he assured Younger: “I had no intention of shooting them.”[37]

Either way, there was still a war to fight and the West to pacify:

Either way, there was still a war to fight and the West to pacify:

CAPTURES IN SLIGO –

BIG ENCIRCLING MOVEMENT

Troops under the command of Major-General McKeon and Brigadier-General Lawlor are carrying out a successful series of operations on a large scale, with Sligo as a base.

On Monday morning [18th September] national troops advanced on the irregular headquarters at Rahelly…The irregulars hurriedly vacated Rahelly House, leaving behind them beds, bedding, and cars and bicycles. They retreated to a wood, which was later shelled by an 18-pounder gun. Sniping continued until night set in, and all the time the encircling movement was being carried out, and the area in which the irregulars and their armoured car now are appears to be completely cut.[38]

(Irish Times, 20th September 1922)

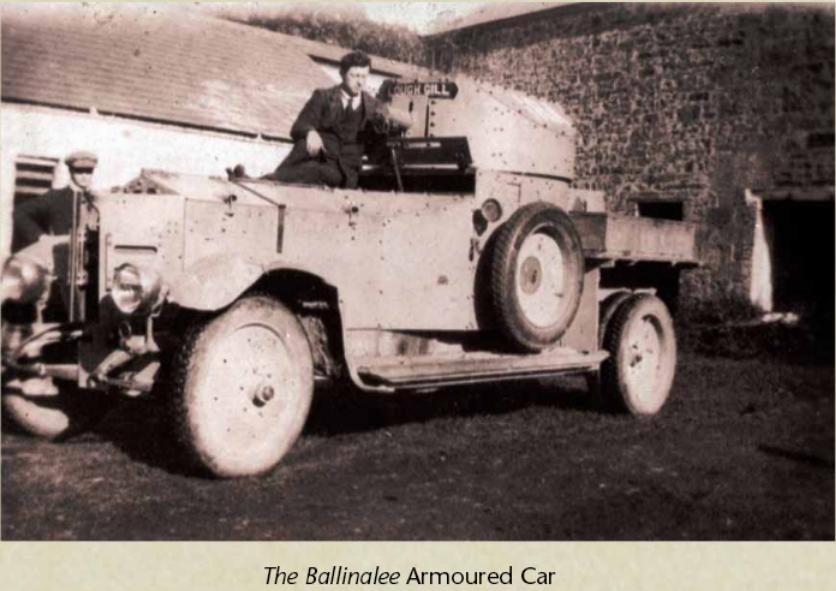

The armoured car in question was the Ballinalee, named after Mac Eoin’s hometown in Longford in an affectionate gesture that became ruefully ironic when the vehicle fell into IRA hands and turned against its former users. And a formidable weapon it could be: Mac Eoin’s strategy to divide his forces into columns and sweep them through the north of Sligo and Leitrim, buttressed by motorcars and field guns, was halted in its tracks when the soldiers under Mac Eoin’s direct command reached Drumcliffe Bridge, a day after they set forth from Sligo town to the sound of a whistle blown by Mac Eoin.

The other side of the bridge had been demolished, with the metal bulk of the Ballinalee waiting menacingly by. Against this, Mac Eoin had an armoured car of his own and an 18-pounder, though the original nine shells of the latter had been reduced to three by that time. Whether the trio would be enough remained an open question when the Ballinalee withdrew, giving Mac Eoin the pleasant surprise of an uncontested crossing.[39]

The other side of the bridge had been demolished, with the metal bulk of the Ballinalee waiting menacingly by. Against this, Mac Eoin had an armoured car of his own and an 18-pounder, though the original nine shells of the latter had been reduced to three by that time. Whether the trio would be enough remained an open question when the Ballinalee withdrew, giving Mac Eoin the pleasant surprise of an uncontested crossing.[39]

Breaking the Resistance

That more or less set the tone for the rest of the fortnight: the Anti-Treatyites would appear to block the way and exchange shots before backing away, allowing the National Army a gradual, but nonetheless steady, advance, enough for it to be reported as such:

RESISTANCE BROKEN –

SEARCHING FOR BODIES IN SLIGO

The operations of the troops in the Sligo-Leitrim area, which had begun a week ago under the direction of Major-General McKeon and Commandant-General Lawlor, continue. The back of the irregulars’ resistance in that sector is now completely broken, and the troops are mainly occupied in searching for dead and wounded in the mountains, and endeavouring to round up isolated parties of irregulars.[40]

(Irish Times, 25th September 1922)

One of those picked up was a lad who, Mac Eoin guessed from the way he was out of breath, had been running dispatches. After three or four rounds of ammunition was found on him, the youth confessed his belonging to the other side. All he asked was to see his mother and sister before being taken away; his sibling, he explained, being due to leave the next day for Australia. Mac Eoin agreed to this and escorted his charge to a nearby thatched cottage, where the mother and sister begged the Major-General to let their kinsman go. She would see that her son stayed at home and out of trouble from now on, the mother promised.

Deciding to take a chance, and perhaps moved by the plight of a woman who would otherwise be left on her own, Mac Eoin acceded. “When you got that kind of assurance it was usually honoured,” he explained to Younger. “Anyway, I found that this was much better than taking prisoners.”[41]

There were, of course, other ways of avoiding the burden of captives:

FIGHT IN THE MOUNTAINS

PROMINENT LEADERS DEAD

Heavy fighting developed during the push of the national troops in the mountains near Sligo on Wednesday [20th September], and many casualties were caused among the irregulars, some of the most prominent leaders being among the dead.

A fierce engagement took place on Wednesday afternoon near Ballintrillick.

It is stated that troops came upon a large party of men, who were engaged in the preparation of an ambush. Both parties were armed with rifles and machine guns, and an engagement immediately developed. The irregulars endeavoured to fight their way back to the hills, when they came in contact with another body of troops. It was here that most of the casualties occurred, and that some prisoners were taken.[42]

(Irish Times, 22nd September 1922)

“That was the end of the war in Sligo,” a phlegmatic Mac Eoin said at the conclusion of Younger’s chapter on this episode. “They had their funerals three days later and after that we had none and neither did they.”

The way he told it, the dead men were the crew of the Ballinalee, which had been sighted on a road by Benbulbin Mountain. Finding the path blocked on both ends, the Anti-Treatyites abandoned their transport and headed uphill, the only escape route left to them – or so they thought, for another group of Pro-Treatyites had been sent from the other side of Benbulbin to cut off such an attempt. Though Mac Eoin was not present, he believed that “when the crew of the armoured car appeared over the crest, my men opened fire and killed them all…which was in accordance with my orders.”

While this falls short of the contemporary reportage of the deaths as part of a ‘fierce engagement’, Mac Eoin was untroubled and unfazed about what he depicted as just another act of war, no less legitimate than the countless others conducted: “We had had most of the funerals up till then and I felt that when they were under arms and on the alert they couldn’t complain if they were shot at.”

Lawlor, who had been coordinating ground manoeuvres in the area, was less judgemental but also vague – evasive, a cynic might think – in his own version of events to Younger: “I sent my men up the mountain and what happened then no one knows.” Except, presumably, the soldiers involved, but Lawlor did not seem in any great hurry to ask them.[43]

On Trial

That Mac Eoin felt the need to justify the deaths alone might raise the brows of his readers, if only by the merest fraction. Other accounts would emerge to portray Benbulbin as not quite the open-and-shut case of Mac Eoin’s narrative. If the pro-Treaty general had a sympathetic ear in Younger, then his enemies could find a like-minded historian of their own.

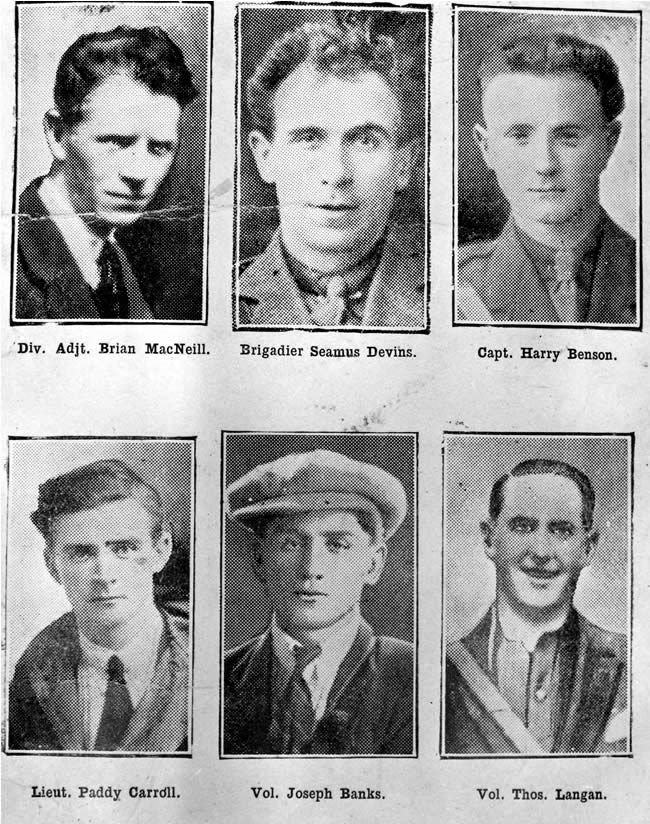

“There was a Free State round-up, personally conducted by MacEoin. All the back of [Brian] MacNeill’s head was blown away which would show that he ran for it,” Tom Carney told Ernie O’Malley during an interview in 1950, twenty-eight years later. “[Harry] Benson was found at the bottom of a ravine after a few days had passed by, and he had several bayonet wounds in him.”[44]

Carney was not a witness – otherwise he probably would have not lived to tell the tale – and he had his own reason for disliking Mac Eoin (as described further), but other accounts would flesh out this alternative take on the one initially reported. One document, now in the Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents, outlined how four of the IRA ‘prominent leaders’ – Brigadier Seamus Devins, Adjutant Brian MacNeill, Lieutenant Patrick Carroll and Joseph Banks – were caught off-guard by Free State soldiers in the guise of allies. After being disarmed and identified, the four were shot dead, despite the reservations of some of their captors. Two more Anti-Treatyites, Harry Benson and Thomas Langan, were entrapped by the same ploy elsewhere and likewise killed, a bayonet being used for posthumous mutilation.

Of the six victims, Brian MacNeill is particularly notable in that his father, Eoin, was not just on the other side of the Treaty divide but a Cabinet Minister in the Provisional Government, no less. More than ninety years later, in 2013, Brian’s nephew, Michael McDowell – who had had a high-profile political career of his own – presented a documentary on the deed, A Lost Son.

“Sifting through the military reports, McDowell unravels a web of duplicity. He persuasively argues that there was a cover-up by senior officers, who lied and fabricated evidence to conceal a premediated atrocity,” according to one reviewer. “McDowell concludes that the killers were acting on the orders of Seán MacEoin…In a humiliating blow to MacEoin’s prestige, Brian MacNeill’s IRA unit had previously captured an armoured car [the Ballinalee] in what was the likely motive for the atrocity.”[45]

Even Younger seemed to sense something was amiss and perhaps sought to mollify any unease on the part of his readers with an anecdote about Mac Eoin tracking down a watch that had been robbed from one of the bodies on Benbulbin and delivering it to the deceased’s widow. Whether the Major-General actually ordered the massacre is another matter, with speculation about wounded pride as a motive being just that – speculation. It is not as if other prisoners had not been taken alive during the Sligo campaign, and even his antagonists described Mac Eoin on other occasions as displaying the same mercy, or at least sense of fairness, that had prompted him to famously spare the helpless Auxiliaries after the Clonfin Ambush in February 1921.[46]

One IRA combatant at Collooney, Broddie Malone – the same who had earlier tried to assassinate Mac Eoin – believed that Lawlor had wanted to use artillery to blast the cottage Malone and his comrades were sheltering in, only for Mac Eoin, who knew them from before, to countermand him and spare their lives. Captured instead, Malone and some other Anti-Treatyites were put to a roadside trial. A National Army sergeant accused the ‘defendants’ of gunning down the late Lieutenant Callaghan while he had had his hands up in surrender, but another Free State soldier testified that Callaghan had died fighting behind a machine-gun. Overseeing the proceedings as an impromptu judge, Mac Eoin allowed the charges to be dropped.[47]

And then there was Robert Briscoe when Mac Eoin chanced upon him stepping out onto a Dublin street. To Briscoe, his foe presented:

A grand burly figure of a man he was, magnificently attired in a new green uniform with red and white service stripes, gold stars on his shoulders, and a shiny Sam Browne belt in the holster of which was a great, ugly .45 revolver with a bright green lanyard.

As Mac Eoin reached for this weapon, Briscoe make a calculation, turned and walked the other way, trusting in his adversary’s well-known code of honour. The gamble paid off. “Briscoe, you bastard,” he heard Mac Eoin roar after him. “You know I wouldn’t shoot a man in the back!”

Years later, Briscoe would make a point of thanking Mac Eoin whenever they met. “The greatest mistake I ever made,” was Mac Eoin’s response, with a shake of his head.[48]

The Man in Charge

Not every portrayal is quite so benign, however, and stories of Good Mac Eoin sit uneasily next to those of Bad Mac Eoin. When Ernie O’Malley, as Acting Assistant Chief of Staff to the IRA, asked, on the 30th October 1922, for names of pro-Treaty officers “who have ill-treated prisoners, or who have acted on the murder gangs” in order to know who was to be “shot at sight”, he added in his dispatch that Mac Eoin and Lawlor were to be included to the list.[49]

Tom Carney had a personal encounter with this dark side of Mac Eoin’s while held inside the old British barracks in Longford. He was retiring to bed when three uniformed men, each in a state of inebriation, entered the storage-room being used for detainment. Mac Eoin was one of them:

They walked down. MacEoin was threatening the prisoners with revolvers in their backs and bombs and they said what they wouldn’t do to the prisoners if they tried to escape. Mac[Eoin] was very drunk and he said, ‘Hello, you don’t know me now. Do you remember the man in charge?’ But it passed off for he didn’t do anything.[50]

Other guests of the government were not so lucky. Noel Browne would recall from his childhood in Athlone “seeing row after row of tricoloured-covered coffins, side by side. To me they were just so many colourful outsize parcels, in a great room in some building.” The sight made so little impression on young Browne that his older self would think it a missed opportunity to not display the bodies, in all their grisly horror, to better deter impressionable minds from repeating the mistakes of the previous generation.

By the time Browne met Mac Eoin, both were Ministers in the Inter-Party Government of 1948-51, with the former general, then in his 50s, appearing to Browne as “a gentle, peaceful man.” When their Taoiseach was going through a particularly difficult time, Mac Eoin “was his usual pleasant reassuring self in his attempt to comfort [John A.] Costello.” His wartime exploits in two conflicts were no secret but, according to Browne:

It was generally believed by the public that in spite of being a soldier, with the soldier’s awful job of daily learning how to kill other men more cleverly, MacEoin…neither wanted to kill, nor be killed.

When discussing his painful memories of that turbulent period, Mac Eoin told Browne, with whom he had struck up a rapport, that he would have preferred to turn his efforts to stopping the Civil War, not fighting it.[51]

Which, of course, was not quite how it played out. Browne was perhaps taking his fellow Minister’s genial demeanour and worthy words a little too much at face value: as GOC Western Division, Mac Eoin was in charge of the five executions at 8 am, on the 20th January 1923, that filled the coffins young Browne beheld. One of the deceased was a local man, the other four from Galway, and the charges against them were unauthorised possession of arms and ammunitions.

In this, Mac Eoin could claim to be only following procedure. Six other death sentences were carried out elsewhere in the country that morning: four in Tralee and two in Limerick, all for the same offences. His thoughts on this matter are unrecorded but, then, the court-martials and their resultant executions were policies Mac Eoin had pushed for in the Dáil. His argument then had been for legally sanctioned killings as an outlet for feelings otherwise to be satisfied by extrajudicial murders.[52]

Mac Eoin’s own behaviour, however, would indicate that one did not necessarily preclude the other.

A Bad Shot

Among the detainees held in the Custume Barracks of Athlone were two senior IRA officers, Michael Kilroy and Tom Maguire, as noted by O’Malley on the 14th January 1923. Though O’Malley was by then himself a captive, he was able to smuggle a letter out of Mountjoy Prison to his Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch. Both Kilroy and Maguire were in danger of being put before a firing-squad, but there was apparently resistance within the Free State authorities to do so, or so O’Malley heard: “I think the enemy are pressing [Seán] McKeown to try them, but I could not vouch for this.”[53]

Kilroy would confirm Mac Eoin’s efforts on his behalf. The fortunes of war had turned drastically since the time Kilroy anticipated the burning of Custume Barracks down around Mac Eoin. After he was brought to that same building, badly wounded from a bullet to the back and under threat of more to his front:

We were to be executed at the time of the Bagenal arrests, and MacEoin made a special journey to Dublin to save me and he said to me, ‘I don’t know the result but I did my best.’

As Kilroy lived to tell his tale, it can be surmised that Mac Eoin’s best was good enough. Kilroy was recounting this to O’Malley in the 1950s, in one of the interviews the latter conducted with former IRA combatants. Right after Kilroy said this, he revealed a very different aspect of his saviour, involving the misfortune of a fellow inmate, Patrick ‘Patch’ Mulrennan, in October 1922:

Mulrennan was shot sitting beside Paddy Hegarty in Athlone. Lawlor fired a few shots at him, then Lawlor and MacEoin were going around making a sport of the prisoners, hitting them with sticks. MacEoin would say when Lawlor fired, ‘You missed him.’[54]

Casually inflicted misery seems to have been a feature of Custume Barracks, enough for another of its unwilling residents, Johnny Grealy, to consider Mountjoy a palace in comparison. Along with the limited food, if it could be called as such, “MacEoin wouldn’t allow the fellows back into the huts once they got out for exercise so they had to walk the compound even in the rain from 10 or 11 until the evening and then we were closed into the huts again,” Grealy said in his own interview.

As for the case of Mulrennan, while Kilroy did not include the results of his shooting, Grealy was able to provide a fuller picture:

Patch Mulrennan raised a window and went in to boil water one day. Someone shouted at him that MacEoin and Tony Lawlor had come in. Lawlor fired as Patch was coming out the window. ‘You missed,’ said MacEoin.

‘Well, I won’t miss this time,’ said Tony Lawlor, and he fired again and Patch died there and then. [55]

Here, Mulrennan’s death is instantaneous. In Tony Heavey’s version, Mulrennan survived long enough for his wound to become infected, fatally so. The details provided by Heavey differ to Grealy’s, but the main point is the same:

Tony Lawlor and MacEoin arrived in the compound. Mulrennan…was sitting down hammering a ring on the floor outside the door…Some fellows, who were in the room, cleared out when they saw MacEoin and Tony Lawlor. MacEoin said something to Tony Lawlor, and Lawlor fired at Mulrennan. MacEoin is alleged to have said, ‘That was a bad shot,’ and Lawlor said, ‘I won’t miss this time,’ and he hit Mulrennan in the thigh. It was neglected, the wound, and he died.[56]

“You’re a bad shot, Tony” – that line, or its latest variant, would be repeated in the Dáil in February 1928, almost six years later, by Dr P.J. O’Dowd, the Roscommon TD for the Anti-Treatyites in their current political guise of Fianna Fáil. O’Dowd was raising the subject as part of his financial appeal for Mary Mulrennan, the deceased’s mother, though the chance to rake the government over the Civil War coals as well was probably too tempting to pass up.

While O’Dowd named Lawlor as the shooter, he refrained from doing so to Mac Eoin, referring to him only as “Colonel Lawlor’s senior officer.” Mac Eoin – by then Quartermaster-General of the National Army – was not present to defend himself or his subordinate, leaving representatives from his party to receive the charge. Due to an escape attempt earlier that day, argued the Minister of Defence, Desmond Fitzgerald, prisoners had been ordered to stay out of certain buildings. The shots fired had been at those who were where they should not have been.

Besides, added Fitzgerald, there was a certain matter of a war being on at the time. Whether these are reasons enough is a question left to the reader.[57]

References

[1] Sligo Independent, 08/07/1922

[2] Ibid

[3] Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1982), pp. 10, 357

[4] Ibid, pp. 357-9

[5] Westmeath Independent, 08/07/1922

[6] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Keane, Vincent) The Men Will Talk to Me: Mayo Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2014), p. 66

[7] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007), pp. 43-4

[8] Ibid, p. 43

[9] O’Malley, The Men Will Talk to Me, p. 197

[10] Ibid, p. 225

[11] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 52

[12] Irish Times, 13/07/1922

[13] Younger, p. 363

[14] Ibid, pp. 363-3

[15] Irish Times, 17/07/1922

[16] Younger, pp. 364-6

[17] Irish Times, 17/07/1922

[18] Longford Leader, 22/07/1922

[19] Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin Archives, P7/B/75, p. 10

[20] O’Donoghue, Michael V. (BMH / WS 1741, Part II), p. 189

[21] Longford Leader, 18/07/1922

[22] Ibid, 22/07/1922

[23] Sligo Independent, 15/07/1922

[24] Mulcahy Papers, P7/B/73, p. 162

[25] Ibid, P7/B/22, p. 11

[26] Irish Times, 29/08/1922

[27] Ibid, 11/09/1922

[28] Ginnell, Alice (BMH / WS 982), p. 65

[29] Irish Times, 29/09/1922

[30] Mulcahy Papers, P7/B/73, p. 55

[31] Ibid, P7/B/74, pp. 102-3

[32] Ibid, P7/B/73, pp. 80-1

[33] Ibid, p. 58

[34] Ibid, pp. 80-1

[35] Younger, pp. 463-4

[36] Irish Times, 16/09/1922

[37] Younger, pp. 464-5

[38] Irish Times, 20/09/1922

[39] Younger, pp. 466-7

[40] Irish Times, 25/09/1922

[41] Younger, p. 469

[42] Irish Times, 22/09/1922

[43] Younger, pp. 469-71

[44] O’Malley, The Men Will Talk to Me, p. 328

[45] McConway, Philip. ‘TV Eye: A Lost Son’, History Ireland (Volume 21, Issue 2 [March/April 2013)

[46] Younger, pp. 470-1

[47] O’Malley, The Men Will Talk to Me, p. 200

[48] Briscoe, Robert and Hatch, Alden. For the Life of Me (London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1959), pp. 172-3

[49] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 309

[50] O’Malley, The Men Will Talk to Me, p. 325

[51] Browne, Noel. Against the Tide (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 2007), pp. 6, 130

[52] Westmeath Examiner, 27/01/1923

[53] O’Malley, ‘No Surrender Here!’, p. 356

[54] O’Malley, The Men Will Talk to Me, p. 69

[55] Ibid, pp. 296-7

[56] Ibid, pp. 147-8

[57] Irish Times, 01/03/1928

Bibliography

Newspapers

Irish Times

Longford Leader

Sligo Independent

Westmeath Examiner

Westmeath Independent

Books

Briscoe, Robert and Hatch, Alden. For the Life of Me (London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1959)

Browne, Noel. Against the Tide (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 2007)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Keane, Vincent) The Men Will Talk to Me: Mayo Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2014)

Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1982)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Ginnell, Alice, WS 982

O’Donoghue, Michael V., WS 1741

University College Dublin Archives

Richard Mulcahy Papers

Online Source

McConway, Philip. ‘TV Eye: A Lost Son’, History Ireland (Volume 21, Issue 2 [March/April 2013)

Irish Times, 4th March 1921:

Irish Times, 4th March 1921: