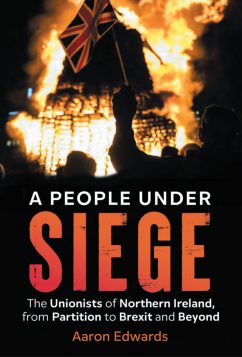

Can Ulster Unionism be reformed? And, if so, into what? These are the central questions posed in Aaron Edwards’ book: at one point, he draws a distinction between ‘Ulster British’ (inclusive, tolerant, good) and ‘Ulster Loyalist’ (not so much), and elsewhere with ‘civic Unionism’ against ‘cultural Loyalism’ (likewise respectively). When confronted with the choice between these two worldviews, however, it is rarely the angels of Unionism’s better nature that wins out, as the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) found when it tried to harness the strength of one in the service of the other.

Can Ulster Unionism be reformed? And, if so, into what? These are the central questions posed in Aaron Edwards’ book: at one point, he draws a distinction between ‘Ulster British’ (inclusive, tolerant, good) and ‘Ulster Loyalist’ (not so much), and elsewhere with ‘civic Unionism’ against ‘cultural Loyalism’ (likewise respectively). When confronted with the choice between these two worldviews, however, it is rarely the angels of Unionism’s better nature that wins out, as the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) found when it tried to harness the strength of one in the service of the other.

It might not have been the most obvious party of peacemakers, formed as it was by members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) while they were serving prison sentences for various terrorist offences. Yet enforced confinement does hold certain advantages; for one, the time to think and take stock of circumstances.

“In the compounds we had these regular seminars,” explained Billy Mitchell, the UVF Director of Operations:

There would have been differences of opinion. There were people still locked in what we would call a ‘DUP [Democratic Unionist Party] mindset’. Others were more progressive in their thinking. And, so, there was this melting pot of ideas and thoughts.

Out of this stew came:

…a consensus that we had to redefine unionism. One, we had to understand what unionism was all about. A lot of volunteers were responding to republican violence…So, none of us went into Long Kesh with an ideology. It was in Long Kesh that we hammered it out.

The creed so forged was, as Edwards describes, a “liberal, left-leaning and working-class alternative to mainstream unionism.” This made it a perfect fit for the PUP, looking as it was to challenge shibboleths in their community. While others railed against the Good Friday Agreement as a betrayal, Mitchell, as the PUP’s senior strategist, saw it representing a “transition, of invitation and of opportunity,” and the chance at “a new era of hope and opportunity.” Unfortunately, the tide of Unionist public opinion was not flowing in his favour, as shown when Billy Hutchinson, his PUP colleague and fellow ex-prisoner, lost his seat in the Northern Irish Assembly in 2003 and later his council seat as well.

Things took another turn for the hard-line with the Flag Protests, when Belfast City Council voted in December 2012 to limit the flying of the Union Jack over its buildings to designated days. Enraged at what they saw as a devious Fenian plot, protestors descended on Belfast City Hall to disrupt the vote, some even succeeding at breaking through the security barriers and into the building before police could intervene. Present at these demonstrations was Hutchison, ruminating to reporters at an impromptu press conference about the ‘de-Britification’ that he said was taking place.

Yet, a decade earlier, the PUP had sounded positively agnostic on the whole question if the statements of Mitchell were anything to go by. He dismissed “Sinn Féin’s preoccupation with flags and emblems” as having “more to do with wanting to remove any visible sign of their failure to break the link with Britain than it has to do with republican ideals.” Even if successful, such cultural coups were “nothing for nationalists to be jubilant about or for unionists to be despondent about.” Fine words, perhaps, but, by 2012, there was plenty of despondency to go about as far as many of the latter were concerned. “The protests are not about the flag, they never were just about the flag,” wrote one editor of a Shankhill-based newspaper. “There is a deep-rooted disillusionment within PUL [Protestant, Unionist, Loyalist] working-class communities that they have been left behind by those in power at Stormont.”

It was a vacuum the PUP moved to fill, and successfully so – at first – winning over 12,000 first preference votes in the 2014 local government elections, with four councillors elected in Belfast and Coleraine, and an influx of new members, albeit many being more in tune with ‘The Sash’ than ‘The Internationale’, in Edwards’ pithy phase. In doing so, the party envisioned as the working-class alternative to mainstream Unionism seemed to have lost its way, in the view of members like Julie-Anne Corr-Johnston.

“More and more people came to join the party,” she recalls:

They were very much disillusioned with the DUP and a lot of it was protest. Some came from the TUV [Traditional Unionist Voice]. And they didn’t join the party because of its policies, because of its vision for it. They joined it because of its reaction to certain events and thought it would give them strength in numbers.

Numbers soon became what the PUP lacked, securing only 5,955 first preference votes two years after its bounce, in the 2016 Northern Ireland Assembly elections and failing to grow its electoral profile. The DUP and TUV, in contrast, saw the return of their natural voters, while the ‘squeezed middle’ demographic passed over the PUP in favour of the Green Party and the People Before Profit Alliance (PBPA). In attempting to weave divergent strands together – ‘civic Unionism’ with ‘cultural Loyalism’ – the PUP had been left merely with frayed edges.

It’s a contrast – and contradiction – that Edwards is well placed to navigate for his readers. The book begins and end with him on the Glorious Twelfth, in 2001 and 2021 respectively, taking in the sight of that most contentious of events: an Orange parade. On neither occasion did things run smoothly. In 2001, on Whitewell Road, North Belfast, a line of police Land Rovers blocked the way, while a Nationalist crowd on the other side hurled bricks, bottles and even golf balls at the thirty Orangemen making an attempt at a parade.

Twenty years later, in 2021, it was the lockdown thanks to the Coronavirus that stymied the big event, though the Eleventh Night bonfires Edwards beheld in Ballymoney, Co. Antrim, made up for the lack of spectacle. These bonfires, Edwards notes, had become much larger and grander than the ones to be found two decades ago, the acrid stink of burnt pallets and melted tyres enough to make him gag while just passing by. “A perfect metaphor for the wrecking of working-class areas,” he muses, while before, in 2001, what had moved him was the plight of the parade participants, thwarted by police and assailed with missiles.

Despite the book’s title, and the frequent depictions by the media of Unionists having a siege mentality, Nationalists, Republicans and what-have-you rarely feature here; the big struggle, instead, being Unionism’s against itself. For all the modern veneration of icons like Edward Carson and James Craig (whose stern, moustached visage adorns the wall mural of an otherwise plain-looking house in one photo), the Northern Irish state, from its inception in the early 1920s, was never entirely confident of the support of the people it had supposedly been created for.

Aspiring politicians standing on a platform of Independent Unionist such as Tommy Henderson or Labour like Harry Midgley threatened to chip away at the hegemony of the Unionist Party. Class was (and, it seems, remains to this day) a major fault line: Henderson worked as a housepainter, while his opponent for the parliamentary seat of North Belfast in 1923, Thomas McConnell, was the managing director of a cattle and horse-trading business. McConnell won, but with a reduced majority. Midgley likewise cut into the establishment man’s majority for West Belfast during the same general election – worse, he had done so by taking almost as many Protestant votes (10,000) as Catholic ones (12,000). Little wonder, then, that Carson sounded close to panic at the next Westminster election a year later, in 1924, when he warned crowds in North Belfast that they were “facing Ulster’s most crucial hour,” with any split on the Unionist vote likely to open the door to a Sinn Féin victory.

Despite such challenges and close shaves, Northern Ireland would remain as it was, made in the sectarian, conservative and heavy-handed image its founding fathers had intended. Nonetheless, hope for a difference remained. Henderson’s next run at a constituency seat, a decade later in 1933, was much more successful, thanks to an artfully choreographed performance which had him arriving on the Shankhill Road on the back of a flat-bed lorry, before speaking from an illuminated pedestal. Notably, his choice of talking points were bread-and-butter ones, easily relatable to his listeners, and it earned Henderson a seat in the Northern Ireland House of Commons.

It is in such grassroots figures, Edwards suggests, that the hope of Unionism – ‘civic Unionism’ over ‘cultural Loyalism’ – lies. This reviewer confesses himself sceptical, despite the book’s best efforts. As of now, the DUP remains the party of choice for the Unionist voter, and even a maverick like Henderson took care to play his own Orange card, emphasising how “his Unionism and his Protestantism were as good” as anyone’s – a lesson anyone seeking to breach the siege mentality of Unionism had best remember.

Publisher’s Website: Irish Academic Press

See also:

Book Review: My Life in Loyalism, by Billy Hutchinson (with Gareth Mulvenna) (2020)