Knowing

In the dark, early hours of the 25th April 1922, tensions that had been simmering for weeks in the town of Athlone, Co. Westmeath, spilled over into bloodshed. Soon afterwards, the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the pro-Treaty military issued its report on the shocking event:

Shortly after midnight on Monday a party of officers left Custume Barracks, Athlone, and proceeded down the town to the Royal Hotel, outside of which they commandeered a motor car. When the party returned to the military barracks it was discovered that one officer was missing.[1]

A search party of four was sent out to find their errant comrade, sometime around 2 am. As they walked towards the Irishtown area of Athlone, they came across a man loitering in a shop doorway.

“Who are you?” asked one of the search party, Brigadier-General George Adamson.

“I know you, George. You know me, Adamson,” came the cryptic reply. Not satisfied, the officers demanded the stranger to put his hands up. When he remained as he was, Adamson levelled a revolver on him.

Suddenly there was a rush and the search party found themselves confronted in turn by a rival group of armed men. When they were disarmed – so read the GHQ report – the man in the doorway drew a revolver of his own and fired point blank through Adamson’s ear, into his head.[2]

Standing

However dreadful, the incident was not altogether surprising. It might even be said that something of its nature was inevitable, given the state of the country.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty signed five months earlier, in December 1921, by the British Government and the plenipotentiaries of Dáil Éireann had seen the end of one war and the stirrings of another. The country was instantly divided on the question of whether or not to accept such terms, a situation heightened rather than mollified when the Dáil narrowly voted to do so in January 1922.

Nowhere were the divisions more keenly – or dangerously – felt than in the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Before they had been united as brothers-in-arms against the might of the foreign oppressor. Now the enemy had agreed to a peace deal that few had expected, and not all wanted, as the insistence on the oath to the Crown made many think that the cure for their country was no better than the disease. With the British Army set to depart for good, each IRA man was left, not so much to savour the victory but to wonder where they stood in the new and uncertain situation.

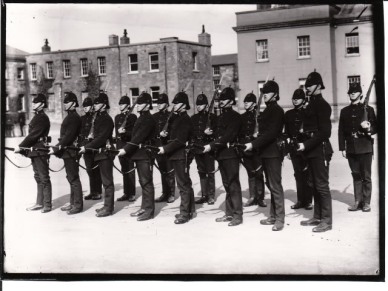

Not that things worsened immediately. It took time for them to deteriorate to the point where a man would be shot in the head on the streets of Athlone. In the first few months after the Treaty, there was still chances to stand together. On the 28th January 1922, the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Midland IRA Division mustered openly for the first time since its inception. About eight hundred men assembled outside Athlone, much to the admiration of a journalist who commented about how:

Of fine physique and displaying efficient military training, the men made the most imposing spectacle as they marched through the town, headed by the Athlone brass band.

Thousands of spectators lined the pavements, including members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), who appeared greatly impressed at the display of the same men they had been trying to arrest months before.

The policemen might as well be graceful losers. ‘WHAT A CHANGE!’ read the headline of a local newspaper as it reported that it was the Athlone IRA Brigade who now granted permission to possess firearms, such as to an officer in the British garrison for a fowling piece. Policing patrols were being conducted jointly by the RIC and the IRA, but for the former this were to last only until its disbandment as per the terms of the Treaty.[3]

After all the violence, it looked to be an orderly transfer of authority, which some might have thought boded well for the future.

Remembering

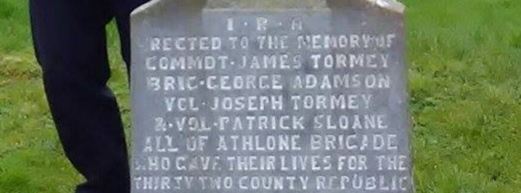

As well as looking to the future, the men of the IRA found time to pay respects to the past. On the 6th February 1922, a Celtic cross was erected at Cornafulla, near Athlone, to the memory of James Tormey, killed almost a year before at that same site. Unveiling the monument was George Adamson in what must have been a poignant occasion for him, considering that he had been present at Tormey’s death.[4]

Tormey had ordered a mobilisation of the local IRA unit with the intent of ambushing a Black-and-Tan patrol as they cycled by Cornafulla. As soon as the group of Tans came into sight on the 2nd February 1921, Tormey recklessly opened fire before the rest of the ambush party, which included Adamson, were ready.

The Tans instantly dismounted from their bicycles and shot back, forcing the IRA to beat a hasty retreat. Tormey was covering the escape when a Tan crept into a lane at a right angle from the main road, outflanking Tormey and shooting him in the head before he could react.

In the confusion, and perhaps fearing another ambush, the Tans had cycled away, leaving Tormey’s body where it lay. Adamson and the others had managed to escape and later, under the cover of night, they removed the corpse by boat down the Shannon and buried it in secret. That was not the end of the matter, as the cadaver was dug up soon afterwards by Tans who took it to Athlone where Tormey’s father identified his son. Only then was the body allowed to rest in the family plot in Mount Temple.[5]

In time, Adamson’s own remains were buried there besides Tormey’s. “Sad to relate,” wrote an old comrade of theirs in later years, “their graves are grossly neglected, being covered with weeds and dirt. There is no monument or anything to mark the place.”[6]

Escaping

As patrols and searches by Crown forces increased, death was never far away. The Athlone IRA had become a victim of its own success, for the string of ambushes inflicted in the latter half of 1920 had stirred the British garrison into a vigorous response. Adamson would have a brush with mortality in March 1921 when he and another man, Gerald Davis, set out on a mission of their own.

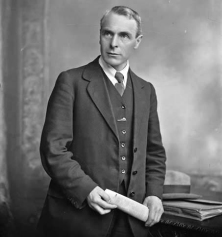

Davis had arrived from Dublin at the behest of GHQ to help organise the Athlone IRA. He made the acquaintance of Adamson, then the Vice O/C of the Brigade, who impressed Davis as being “a fine type of man, well built, a good athlete and a very good fellow all round.”

The Brigade was in not such good shape, its members having scattered to avoid the attentions of the British authorities. Still, David was game and in Adamson he found a kindred soul. When they received word of two Tans who were in the company of a pair of local women, Davis and Adamson set out with revolvers to the farmhouse outside Athlone where the women lived.

They found one of the Tans in the yard and quickly disarmed him. Adamson stood guard over their captive – the intent being to rob them of arms rather than to kill – while Davis went in search of the other. When he found him hiding behind a clamp of turf, the Tan shot at him before making a break. David fired after the fleeing man, grazing his thigh but nothing more, the mismatched ammo in his Colt pistol rendering its aim difficult.

Davis doubled back at the sound of Adamson shouting to find that the prisoner had turned the tables and pinned Adamson to the ground. A big man, the Tan had wrestled the gun off his former captor and used it to shoot Adamson in the chest. Davis shot the Tan in the side, wounding him, just in time for the second foe to return.

Davis had by then been wounded as well, in the arm though he did not seem aware of when he had been hit. He fired at the second Tan to keep him back and then helped the bleeding Adamson to his feet. They both fled at this point, their plan in tatters. Adamson had lost his revolver in the tussle and they had failed to rob the Tans of theirs as intended, but at least they were alive, if barely in Adamson’s case.

They retreated across the Shannon to a friendly house where Adamson was treated for his chest wound. Davis’ arm went septic for a while but he recovered, as did Adamson who remained at large by the time the Truce came in July 1921. Davis was not so lucky, having been arrested in a British round-up and then – to add insult to injury – identified by one of the Tans he and Adamson had tried to mug.[7]

It was all part of the trials and tribulations of running an insurgency but, with the signing of the Treaty, the war was done and the worst over. At least, that is what Adamson and his peers could have been forgiven for thinking.

Dividing

Colonel Anthony Lawlor’s first thought on the Treaty had been “we can’t touch that.” It did not give Ireland enough in his opinion, and Lawlor feared that the people would be content with that and go no further towards complete independence. Lawlor would be denied the luxury of such long-term thinking when Patrick Morrissey, the O/C of the Athlone Brigade, stalked into his office in the Athlone Military Barracks that was also the base for the IRA Midlands Division.

Their commanding officer, Major-General Seán Mac Eoin, was away in Dublin, leaving Lawlor in charge. Dublin was also where Morrissey had just returned from, a forbidden visit that had marked the man with a new – and, as far as Lawlor was concerned, an unpleasantly defiant – demeanour as he stood before Lawlor, legs wide apart and a revolver protruding above his belt, having not bothered to salute him.

“We’ve decided to stand by the Republic,” Morrissey told him, according to Lawlor’s recollections.

“We’re all standing by the Republic,” Lawlor insisted.

“You’re not,” Morrissey shot back.

However dismayed, Lawlor could not have been hugely surprised, for the controversial IRA Convention had taken place the previous day, on the 26th March 1922, at the Mansion House in Dublin. It had been promised by the Minister of Defence, Richard Mulcahy, on behalf of the IRA GHQ as a way of settling the differences fostered by the Treaty. Mulcahy had then pulled a volte-face and banned attendance on threat of dismissal.

That so many IRA members, including some from the Athlone Brigade such as Morrissey, could be found in the Mansion House on the day, regardless of what had been ordered, did not bode well for the GHQ’s continued authority.

Reasserting

At that moment in Athlone Barracks, it was Lawlor’s own authority that he had to worry about. He stood up, thinking quickly, and told Morrissey to summon the men onto the parade ground. When they were assembled, Lawlor played the part of the army drill-sergeant.

“I blackguarded them,” he recalled. “Told them they were the worst looking crowd I’d ever seen, and that if they were going to fight for a Republic none of them was likely to accomplish very much.”

Lawlor began to drill them, an unexpected move that put him back in charge. He told them to stack their weapons in the armoury and gave them a five minute respite. When he called them again to the parade ground, he made sure they were well away from their arms, which were being stored surreptitiously away by those officers who had remained loyal to GHQ.

All the while, Lawlor carried a pistol in each hand and warned his men that he would shoot if they so much as challenged him. He did not dare not shoot, he told them candidly, if he wanted to continue in his command.

This was enough to overawe the men but not indefinitely. When the men realised they had been gulled, they clamoured to reclaim their stolen weapons. Mac Eoin returned to the Barracks to find near pandemonium as Lawlor and his handful of partisans, including Adamson, stood in a thin line between the armoury and their own enraged men.

While Lawlor had been subtle, Mac Eoin was direct. After calling the men into line, he challenged Morrissey, standing at the front of the ranks, if he was prepared to follow the orders of the Dáil.

Morrissey tried hedging, saying no but that he would still obey any that came from Mac Eoin. For Mac Eoin, this was not good enough, pointing out that he had no authority save what the Dáil granted him. When Morrissey refused to budge, Mac Eoin ripped his Sam Browne belt off him, swung him around and shoved him out through the Barracks’ door. Mac Eoin proceeded down the ranks, meting out the same rough treatment to all else who refused to toe the line.

“That was not in any code that I know,” Mac Eoin later admitted, “but it was an effective method of dealing with the situation.”[8]

Reassembling

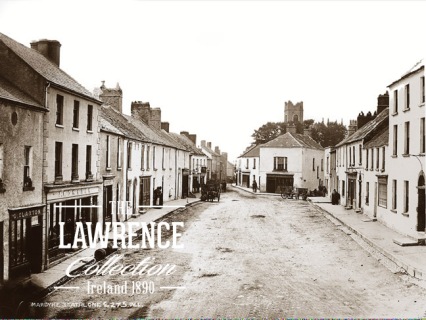

Effective – up to a point. Banishing the dissenting officers was one thing, making them disappear quite another, as shown when they retreated to the Royal Hotel in Marydyke Street, Athlone. There, Morrissey addressed his compatriots from a window, appealing to them to not say or do anything that would shame the name of the Athlone Brigade.

To nip things in the bud, Mac Eoin issued a proclamation to the tradesmen of Athlone. All costs contracted by the IRA up to and including the 25th March would be honoured, after which he would not be responsible for any more unless a written order was presented, signed by his Divisional Quartermaster.

“I accept no liability for any Brigade order owing to the suspension of the Brigade,” Mac Eoin warned.

Lawlor clarified this in an interview with a local newspaper on the 4th April. He explained that certain officers of the Athlone Brigade had repudiated the authority of the Dáil, the IRA GHQ and Mac Eoin. Therefore, these malcontents had been suspended. The Athlone Brigade would continue under the authority of Brigadier Adamson, promoted from Vice O/C to acting commander. All further officers who refused to obey the orders from their lawful superiors were to be regarded no longer as soldiers but civilians.[9]

But Lawlor was trying to shut the door to a half-empty stable. Two days earlier, Morrissey had led six hundred men from the Athone Brigade in officially breaking ties with their pro-Treaty colleagues. He announced to the parade of men that he had received word from the IRA Executive, formed from the Anti-Treatyite leaders at the March Convention, to reaffirm their allegiance to the Republic.

The men uncovered their heads and stood with raised hands as Morrissey administrated the oath of loyalty to them. Afterwards, Morrissey again impressed upon them the importance of discipline, and specifically not to interfere with the men on the other side.

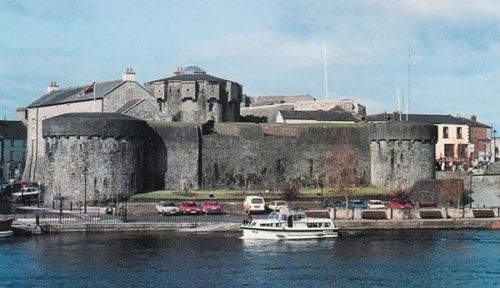

An incident on that same day hinted at how matters were escalating beyond words and proclamations. Sergeant-Major Shields had left the Barracks – renamed the Custume Barracks in honour of the 17th century defender of Athlone – seemingly as a deserter. When two pro-Treaty officers stopped him in the street, Shields made a grab for the revolver of one before attempting to run and received a warning to stop, followed by a bullet to the leg when he did not.

Despite the drama, Shields did not seem to belong to either faction, as evidenced by the lack of reaction. A certain kind of peace was allowed to continue for the next six days.[10]

Clearing

On the evening of the 8th April, Mac Eoin entered the Royal Hotel, now the full-time base of the anti-Treaty IRA in Athlone. Morrissey was absent, leaving McGlynn, the acting commander present, to be told by Mac Eoin that he and his men were to depart by 9 am the next day. Shortly afterwards, a priest, Father Columba, also visited the hotel and advised the men there to comply.

Morning came to find the Anti-Treatyites still defiantly inside. Colonel Lawlor made his way towards the hotel shortly before 2 pm, meeting McGlynn on the way. When McGlynn again declined to vacate, he was arrested and taken to Custume Barracks. Lawlor repeated the demand to the next acting commander in the hotel, Captain Hughes, who likewise refused.

A quarter of an hour later, Lawlor had summoned enough of his soldiers to surround the Royal Hotel, complete with machine-guns. The garrison remained where they were behind the barricaded windows and sang The Soldier’s Song, the unofficial anthem of the revolution since its early years.

Conflict seemed imminent and all civilians nearby hurriedly made themselves scarce. Another priest, Father James, appeared on the scene to appeal for calm for the sake of the women and children in the surrounding houses. This managed to bring the leaders of the respective sides together and, after some discussion, it was agreed that the Anti-Treatyites would indeed leave the Royal Hotel by 5 pm that day. They could take their equipment with them and McGlynn would be released.

With that, the Pro-Treatyites withdrew to their Barracks. The other faction was as good as its word. At the designated time, about fifty men could be seen leaving the hotel, marching – according to a local newspaper – “good-humouredly away.”[11]

Returning

Even if genuine, the good humour did not last long.

On the 11th April, the anti-Treaty IRA returned to reoccupy the Royal Hotel, along with a grocery store that lay directly opposite, as well rooms over a bakery on the same street. Barricades were quickly erected in the windows of these buildings, with armed guards seen behind them by the inhabitants of Mardyke Street, many of whom swiftly fled for fear of an imminent battle.

Their concerns appeared well-founded when Mac Eoin arrived with a force of his own men from Custume Barracks, who occupied in turn a shop and a residence on Mardyke Street, as well as a store on the adjacent Dublin Street, after which they set up barricades of their own.

War seemed inevitable until four priests – including Father James from before – intervened and induced Mac Eoin and his opposing counterpart, Commandant-General Seán Fitzpatrick, to meet. After a short exchange, an adjournment for an hour was agreed upon.

During this lull, the priests requested all public-houses to close. “Business was at a stand-still, and the people moved about in suspense,” reported the Irish Times.

As a result of a subsequent meeting between the two leaders, conflict was again averted, much to the relief of the citizens. For the past few days, they had been helpless witnesses to the manoeuvrings and military brinkmanship conducted in their own town.

The Anti-Treatyites were to stay in Athlone, based once more in the Royal Hotel, and there the situation remained until fourteen days later, on the night of the 25th April, when a hapless George Adamson was shot in the head.[12]

Confronting

Mac Eoin was the first to arrive on the scene. At the inquest in Athlone the next day, Mac Eoin told of what he had seen and done that night.

He had returned from Tralee, Co. Kerry, the previous evening, and was staying at the house of a friend, Mr Duffy, when he heard four shots that sounded as if they had come from directly outside. Springing out of bed, Mac Eoin whipped up the revolver from where he had left it on a table and dashed to the window. Leaning out, he heard the sounds of running footsteps and saw a man in a laneway opposite the house.

Mac Eoin called out: “Halt! Who goes there?”

“Friend,” came the odd reply, perhaps made just to avoid being shot at.

From where he was, Mac Eoin thought he could make out in the dark the object on the ground outside. As he did so, someone shouted: “A man is dying on the street!”

Throwing on some clothes, Mac Eoin rushed out to find Adamson on his back, blood pouring out of his ear. Mac Eoin raised him up in his arms and sent Duffy, who had come out to assist, for a doctor and a priest, the last a sober acknowledgement of Adamson’s chances. A strong man, Mac Eoin carried the victim inside, before heading off towards the Royal Hotel.

On the way, he met Duffy and Father Columba, one of the four priests who had helped arrange the truce – for what it was worth – a fortnight ago. Duffy told him of how he had been held up on the street by masked men while looking for the priest.

That made Mac Eoin all the more determined to reach the Royal Hotel, where he found several Anti-Treatyites, including Commandant-General Fitzpatrick from before. Mac Eoin asked Fitzpatrick if all his men were inside and accounted for. When Fitzpatrick replied in the affirmative, Mac Eoin retorted that there was no use spouting such falsehoods. George Adamson had been murdered, Mac Eoin said, and demanded to know what Fitzpatrick knew of it.

Fitzpatrick, according to Mac Eoin’s testimony, replied: “Be straight with me and I will be straight with you. Four men arrived here tonight, and were talking business with me. They went out and returned, saying that their car was gone, and went out again in less than ten minute afterwards. I heard shouting.”

Fitzpatrick added that he did not know the names of these four. One of the other Anti-Treatyites present piped up to say that he did not know the men either, only that they appeared to be acquainted with Captain Macken, who had ordered that they be admitted in the first place

For his part, Macken said that he only knew one of them, this being a Commandant Burke, which was not a name that meant anything to Mac Eoin.

Also present was Gerald Davis, Adamson’s partner in the botched robbery on the Tans. Upon release from prison as per the terms of the Truce, Davis had re-joined the Athlone Brigade, taking the opposite side to Adamson on the Treaty question. When asked in turn, Davis admitted to knowing the foursome but refused to divulge their names.[13]

Arresting

The news of the shooting seems to have rattled Fitzpatrick as much as enraged Mac Eoin. After Mac Eoin departed from the hotel, Fitzpatrick came to a decision and dispatched a message after the other man to inform him of it:

In view of the attitude which you adopt as a consequence of the regrettable shooting which occurred some hours ago, I have, after consultation with my officers, and with a view of avoiding bloodshed, decided on leaving the Royal Hotel, and taking up quarters elsewhere.

I repeat that the responsibility for the shooting rests not with me. I sincerely regret the occurrence.

Mac Eoin was not mollified. At 6 am, his Pro-Treatyites surrounded the hotel, with Mac Eoin issuing an ultimatum to Fitzpatrick inside:

I hereby charge you and all officers and men in the Royal Hotel with unlawfully conspiring with a commandant and others, unknown, to slay and murder Brigadier-General Adamson, O.C., Athlone Brigade, IRA.

I further charge the Commandant mentioned, and others known to you, with the murder of the above named officer. I hereby call on you to surrender all men and officers in the Royal Hotel on receipt of this, allowing 15 minutes for reply of surrender, and after the expiration of that time I [will] open fire, and do so as the lawful authority, charged with the peace of the district.

Knowing he was beaten, Fitzpatrick wrote back:

In reply to your demand, I have no choice but to surrender. I must assert that I am not in any way responsible for the shooting.

Fitzpatrick’s attempt to retreat with dignity intact had been coldly denied. He bowed to the inevitable and surrendered, being led away with his men to detainment inside Custume Barracks.[14]

Mourning

Adamson died a few hours after being shot, by which time a crowd had gathered outside his hospital to pray for his recovery. The lowering of the tricolour over Athlone Castle was enough to break the news to them and the rest of the town, where he had been known and well-liked.

The 25-year-old native of Moate, Co. Westmeath, had had a brief but eventful life. Previous to his service in the Athlone IRA, he had fought during the Great War, earning a Mons Star and a Distinguished Conduct Medal for conspicuous bravery. That this had been part of the same British Army he would later oppose was one of the many ironies of the period, as was the grim fact that his end had come not at German or British hands, but that of his fellow countrymen.

Fittingly, IRA members and ex-servicemen from the British Army were among the ten thousand-strong crowd who attended the funeral two days later. All business was suspended in Athlone and Moate, with shops closed and window blinds drawn, as the guards of honour, in full uniform and holding their rifles reversed, accompanied the tricoloured-draped coffin as it was carried through the streets of Athlone on the shoulders of Adamson’s colleagues.

Mac Eoin in particular was hit hard by the killing. Among the speakers at the funeral, he was “visibly affected,” according to a local newspaper, as he “delivered a short oratory at the graveside, and paid a glowing tribute to the many qualities of the deceased.”[15]

At the next session of the Dáil in Dublin on the 26th April 1922, President Arthur Griffith spoke of the “foully murdered” Adamson, who “died for his country as truly as any man ever died for it.” When Harry Boland was unwise enough to refer to “unfortunate business in Athlone”, the pro-Treaty benches reacted like a scalded cat.

“Surely, by goodness, it has not come to this, that the shooting of a man is to be treated as ‘business’,” lambasted W.T. Cosgrave. “The Deputy, who may have made it in the heat of the moment, has now time to alter it.”

“Of course I did not mean to suggest that murder is a business,” Boland said hastily.

But Cosgrave was merciless: “’Unfortunate business’ is what you said.”

“’The unfortunate death of a soldier in Athlone’,” Boland amended, backtracking in full.

“That is better,” Cosgrave allowed. “A little bit better.”[16]

Inquiring

At the inquest in Athlone on the 26th April, the day after the shooting, the jury had some choice things to say, not least about the state of the country in general:

We desire to express our abhorrence of this and other un-Irish acts, now of too common occurrence, and while trying to be impartial, we desire to protest against the robberies, raids, stealing from trains, and stealing of motor cars in this district, and we call on the authorities to put it down at once.

J.H. Dixon, the solicitor for the pro-Treaty military authorities, expressed, on his own behalf and for the people of Athlone, sympathy for Adamson’s father, who was present with other relatives. Seán Mac Eoin seconded this, adding that the late Brigadier-General had been a man the Army was proud to have had. His family did not need to be assured of the sympathy of the Army, for they had full evidence of it already. As further proof of Adamson’s valour, his father was handed the four medals he had won for distinguished service in the Great War.

After Mac Eoin had testified to what he had seen that night, it was the turn of Dr MacDonnell. He told of how he had found the victim unconscious in Mr Duffy’s house, where Mac Eoin had brought him. Together with a second doctor to arrive, they had plugged the large wound in the left ear. With some effort, they succeeded in partly reviving Adamson, who managed to utter a request to be taken home. After bandaging his head, the doctors helped their patient to the barracks.

Next up on the stand was the military surgeon. He had examined the body that morning, and told of how he had found two wounds, an entrance wound high up on the back of the head, the other an exit wound in the left ear. In his opinion, death had been due to shock, haemorrhage and compression of the brain.

An eyewitness to the shooting, Lieutenant O’Meara, reiterated much of what had already been reported. He had been one of the four-strong party who went out that night with Adamson. When they returned to their barracks, two of their number were noticed to be missing. It was while searching for them in Athlone that they spied a man in a doorway.

When Adamson challenged the stranger, while ordering Lieutenant Walsh to cover him with a revolver, the man had merely said: “It is all right, George, I know you, and you know me,” adding, “you are George Adamson, and you know something about the car that is gone.”

Eight others suddenly appeared, shouting: “Hands up! We mean it, George. Put up your hands!”

After the four Pro-Treatyites were disarmed, O’Meara heard several shots ring out, followed by the sight of Adamson crumpling to the ground.

The coroner for Co. Westmeath concluded from the hearing that this had been an act of murder, pure and simple. He left the matter with the jury, who returned to deliver the same verdict as the coroner. Which was reasonable enough – it did not seem like a complicated case, after all.[17]

Replying

It was a sign of the times that the official report would so casually, almost innocently, mention officers of its own army engaging in car theft, a detail honed in by Thomas Johnson, Secretary of the Labour Party, in a letter sent on the 27th April to the press.

“By what authority have military officers commandeered a motor car outside a hotel?” Johnson demanded. “Does this not indicate a state of mind alien to the conception of civil law?”

The stolen vehicle would play a larger role in the statement released by the Four Courts, the base of operations for the anti-Treaty IRA leadership, and written by Timothy Buckley, Quartermaster of the Third Southern Division (encompassing Offaly, Laois and North Tipperary). Buckley had been present that night in Athlone and so was able to give the Anti-Treatyites’ version of events:

On the night of the 24th inst., I, with the Commandant [Tom Burke], Adjutant [Joseph Reddin], and Q.M. [Seán Robbins] of Offaly, No. 2 Brigade, motored to Athlone to see Commandant General Fitzpatrick, re transfer of arms.

While engaged with him in his quarters, our motor was stolen from where we had it outside the door. We followed in the direction in which we believed the car had been taken, but could not find the party who took the car.

The men heard their vehicle being driven through a backstreet, towards the Custume Barracks. As the military compound was in Pro-Treatyite hands, they knew they would not be retrieving their car anytime soon. For lack of other options, the four stranded men proceeded into town to find another car to hire for their return journey to Birr, Co. Offaly.

But the theft was not to be the end of that night’s drama for them:

We called up a Mr. Poole in the adjoining street, and were just asking for one of his cars when the Q.M. [Robbins], Offaly, No. 2, was held up about ten yards from where Commandant Burke and I were standing.

In the brief scuffle, Robbins was able to disarm two of his assailants. As Reddin and Burke came to his assistance, the other men ran away, with only one of them stubbornly holding his ground with his hands in his pocket. Burke was confronting this man, who they later learnt was Adamson, when they were abruptly fired upon from the other side of the street.

In the dark, Buckley could not see who the shooter was. He fired back twice with his automatic, and the mystery gunman ran off, pausing only to fire several more times at them from further up the street.

Such was the confusion that Buckley was not sure what was going on, only that he saw Adamson suddenly collapse in the middle of the street. With the shooter now gone, the four Anti-Treatyites rushed to the fallen man’s aid.

We took him off the street and tried to get him to sit upright, but we saw and believed that he was almost beyond human aid. In order to give his friends a chance of helping him, we left the street in their possession, left the town on foot and walked as far as our Divisional area.

“The death of Commandant Adamson is very much regretted,” Commandant Burke added in a brief footnote to Buckley’s statement, as he stressed his group’s lack of complicity.[18]

Brooding

One of the residents of Athlone was the future politician, Dr Noel Browne. Then six years of age, he was woken by his father, who urged his children to lie flat on the floor. From outside came the sounds of gunfire, mixed with those of running feet. A voice shouted out “don’t shoot!”, though Browne was unsure as to whether that particular auditory detail had actually occured or if he only imagined it.

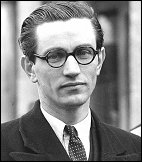

But the blood on the street the next morning was real enough, dried and black and still visible despite the efforts to hide it with a potato sack. The memory of “this awful example of a man’s unique capacity to kill cruelly a fellow man” stayed with Browne. In 1948, twenty-six years afterwards, he met Mac Eoin, both now ministers in the Inter-Party Government. Browne told him about that night in Athlone, when he had first heard the older man’s voice outside his bedroom window. The two became friends as well as co-workers, with Browne thinking Mac Eoin, then in his fifties, a “gentle peaceful man.”[19]

Time had perhaps mellowed the old warrior. Mac Eoin would emerge from that fateful night a changed soul. Before, he had been noted for his chivalry, such as when he had spared Auxiliaries captured at the Granard Ambush of February 1921, going so far as to have the wounded tended to. The Mac Eoin after Adamson’s death was a harder, colder character, with no patience now for talk of peace and compromise.

When the Dáil met the next month in May 1922 to discuss a possible ceasefire between the increasingly fractious IRA sects, his was the dissenting voice as he expressed incredulity that things could be resolved so amiably. Instead, he called for a tougher line on those he saw as the villains of the piece.

“Men are engaged in the pursuit of men charged with serious offences,” he lectured the other TDs. “Justice demands that certain things be done.”[20]

Soon afterwards in September, with the Civil War in full swing, Mac Eoin told the Dáil that: “If I was sure of the man who murdered General Adamson, and if I met him on the street, I would shoot him.”

This was said as part of the proposal to establish army courts to deal with the anti-Treaty prisoners. Once again, Thomas Johnson acted as the closest thing the Dáil had to an opposition leader as he pushed for these courts to be headed by a legal professional, instead of being purely military in nature. To Mac Eoin, however, only a soldier could appreciate the situation of another.

“The reason I would shoot him then,” he continued, “was because there was no law but the law that was vested in me as the Competent Authority of the area. Pass the law that is now asked, and there would be no necessity for me to shoot him, because there would be a legal method of dealing with that individual.”[21]

Later that session, he dismissed the idea that an armistice could be arranged. “It will be the same as the last truce,” he warned, having learnt the limits of patience. “It will be all one-sided, and you cannot have that.”[22]

Even years afterwards, Mac Eoin never wavered in his belief that Adamson’s death had been cold-blooded murder. When he wrote to the Pensions Board in 1929 on behalf of Adamson’s mother to urge for financial assistance, he told of how and why her son had met his end: “The rest of the officers of the Brigade who had turned Irregular always regarded Adamson as a traitor, that he let them down by his action at the meeting.”[23]

Blaming

Some on the anti-Treaty side nursed their own theories.

Liam Carroll was among those Anti-Treatyites present in Athlone that night, along with five others inside Claxton’s Hotel. When they heard shots outside, they quickly hurried out of town by foot, leaving their car behind in their haste to avoid trouble. Such was the confusion that Carroll was able to return the next day and retrieve their vehicle, which had been left untouched. He had not witnessed what happened, but later told the historian Uinseann MacEoin (no relation to Seán Mac Eoin) in 1980 how “Republicans believe [the shooting] was done by one of [Mac Eoin’s] bodyguards.”[24]

Another Anti-Treatyite who had been stationed in the area, Walter Mitchell, went further, suggesting to Uinseann MacEoin that it was Seán Mac Eoin himself who had been responsible. As for the possible reasons why, Mac Eoin was jealous of the other man, “being good in an ordinary scrap, [but] he was completely uneducated”, while Adamson “had far more military science” (descriptions for which, it must be added, we have only Mitchell’s word).

In contrast, Mitchell believed that “no Republican would set out to slay George Adamson.” After all, the Adamson Mitchell remembered had been a “fine soldier, hot-tempered and all that, but he was able to handle men well, including parade formation on the barrack square.” Still, Mitchell appeared less aggrieved at his slaying and more about how the Pro-Treatyites had exploited it for sympathy purposes.[25]

Carroll and Mitchell may not have been the most objective of sources, but even the victim’s brother thought something was amiss. Writing to the Minister of Defence almost twelve years later, in March 1935, as part of his pension application, Joseph Adamson told of how he had happened to overhear, while stationed in Dublin with the Free State army during the Civil War, Mac Eoin’s name mentioned in a conversation. What was said convinced Joseph that the man in question had fired the fatal shot on George, eight months before. When confronted in private about this, Mac Eoin confessed – according to Joseph, anyway – though he later retracted, leaving Joseph with little else to do until he left the military over an unrelated matter.[26]

Quite what the Minister was supposed to do with this exposé is uncertain, as was Joseph’s motive. He seems to have made no further effort to pursue the matter, nor make it known outside the files of his pension claim, and his accusation against Mac Eoin did not stop him from citing the former general as a reference – a strange favour to ask of someone you believed killed your relative.[27]

Deciding

Meeting such accusations head-on fuelled Mac Eoin at the second inquiry, held on the 25th May, at the Newman House on St Stephen’s Green, Dublin, site of the National University. Unlike the first inquiry, which had been dominated by the Pro-Treatyites, this one consisted of attendees from both sides. To stave off further violence, a truce had been signed by the military heads of each IRA faction and, for a while, a spirit of reconciliation pervaded the country, with fraternal ties tentatively renewed and even talk of the two sundered wings reuniting.

But Mac Eoin was in a far from obliging mood when he took the stand inside the Newman House. Dismissing the rumour that he had been the one responsible for Adamson’s shooting as a mere “propaganda stunt”, he argued for the impossibility of such a notion on the grounds that “you cannot shoot unless you fire. You cannot kill unless you fire. My revolver is as full now as it was that day. There is none out of it since.”

He retold his version of that night in Athlone, giving his audience the impression that Adamson had been anticipating something would happen – and that he and Mac Eoin had been unusually close for a commander and his subordinate. In court, Mac Eoin pointed to a ring he was wearing, and told how Adamson, while visiting him at Mr O’Duffy’s house, had taken the ring off his own finger and put it on Mac Eoin’s, saying: “Every time you look at that, think of me.”

Soon after, Mac Eoin continued, when he saw Adamson stricken in the street, he thought back on the ring and wondered if Adamson had had some information about an attempt to be made on his life. Instead of telling Mac Eoin about it, he had gone out to face it alone.

“I know that is not so,” added Mac Eoin on the stand, “but that is what appeared to me at that moment.”

Certain statements Mac Eoin had made to the press came under scrutiny when P.J. Ruttledge, the legal counsel for the anti-Treaty IRA, cross-examined him. If Mac Eoin had been in a righteously angry mood, then Ruttledge sought to match him, outrage by outrage.

Ruttledge: Are you aware that that has gone through three-quarters of the earth, blackguarding a force –?

Mac Eoin: It has just gone as far as the propaganda has gone that I shot him from the window. That statement is an answer to the other.

Ruttledge: You say a certain man did a certain thing. I want to know have you evidence on which to base that charge?

Mac Eoin: There will be evidence here on which to base that charge.

The atmosphere was sufficiently testy at one point for Tom Hales, the president of the court, to ask J. H. Dixon, again the solicitor for the Pro-Treatyites, to moderate his choice of words.

“I wish you would leave out the word ‘murder’ altogether,” Hales said.

“Very well, sir, ‘causing death’,” Dixon said, before adding: “Causing death is very obnoxious. At the same time, I think it will get down to a stage when we cannot have any fineness about words.”

Much of the inquiry was spent recapping the two different, and contradictory, versions of Adamson’s demise. The witnesses from the pro-Treaty forces had it that their late comrade had been callously gunned down, while those for the Anti-Treatyites insisted that his death had been the result of an alteration that spiralled out of control and where, given the confusion, it was impossible to determine culpability.[28]

When the court reassembled on the 1st June to announce its verdict, it showed it had decided on the more cautious interpretation:

We find that the much-regretted and tragic death of the late Brigadier Adamson, Athlone Brigade, Midland Division, I.R.A., resulted from a series of events on the night of the 25th April, accompanied by indiscretions on both sides.

Following the seizure of a car from the Executive Forces, I.R.A., at a late hour that resulted in a hold-up of a man who happened to be an officer of the [anti-Treaty] Forces. Concurrently his commander arrived on the scene, and the discharge of a single shot immediately brought about a burst of firing, in the course of which Brigadier Adamson was fatally wounded by some persons unknown.

The Court cannot determined from the evidence the responsibility for the discharge of the first shot, whether accidental or otherwise, but express the firm conviction that the shooting of Brigadier Adamson was not premeditated.[29]

Given the lack of hard evidence and conflicting viewpoints, there was perhaps little else the court could have said. George Adamson’s death remained, and continues to be so, a mystery.

References

[1] Westmeath Guardian, 28/04/1922

[2] Ibid

[3] Westmeath Examiner, 04/02/1922

[4] Ibid, 11/02/1922

[5] Lennon, Patrick (BMH / WS 1336), pp. 10-1

[6] O’Meara, Seumas (BMH / WS 1504), p. 47

[7] David, Gerald (BMH / WS 1361), pp. 12-4, 16

[8] Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Fontana/Collins, 1970), pp. 241, 255-6

[9] Westmeath Examiner, 01/04/1922

[10] Irish Times, 04/04/1922

[11] Ibid, 11/04/1922

[12] Ibid, 12/04/1922

[13] Ibid, 27/04/1922

[14] Ibid, 26/04/1922

[15] Westmeath Guardian, 28/04/1922

[16] Dáil Éireann. Official Report, August 1921 – June 1922 (Dublin: Stationery Office [1922]), pp. 235-6

[17] Irish Times, 27/04/1922

[18] Ibid, 28/04/1922

[19] Browne, Noel. Against the Tide (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1987), pp. 5-6

[20] Dáil Éireann, August 1921 – June 1922, p. 368

[21] Dáil Éireann. Official Report, September – December 1922 (Dublin: Stationery Office [Dublin]), p. 899

[22] Ibid, p. 947

[23] Military Service Pensions Collection, ‘Adamson, George’ (2/D/2), p. 131

[24] MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), pp. 269-70

[25] Ibid, pp. 386-7

[26] Military Service Pensions Collection, ‘Adamson, Joseph’ (MSP34REF16521), p. 3

[27]Ibid, pp. 15, 49

[28] Irish Times, 26/05/1922

[29] Ibid, 02/06/1922

Bibliography

Newspapers

Irish Times

Westmeath Examiner

Westmeath Guardian

Books

Dáil Éireann. Official Report, August 1921 – June 1922 (Dublin: Stationery Office [1922])

Dáil Éireann. Official Report, September – December 1922 (Dublin: Stationery Office [1922])

MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

Browne, Noel. Against the Tide (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1987)

Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Fontana/Collins, 1970)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Davis, Gerald, WS 1361

Lennon, Patrick, WS 1336

O’Meara, Seumas, WS 1504

Military Service Pensions Collection

Adamson, George, 2/D/2

Adamson, Joseph, MSP34REF16521

The column stayed in the Summerhill area for over a fortnight where Tormey utilised his British Army expertise to put it through a training course. Emboldened by their earlier success and not wanting to rest on their laurels, the Volunteers set up three ambush positions in succession for RIC cycle patrols, only for none to show. Skirting Athlone on its Connaught side, the column packed up and crossed the Shannon, aiming to set up camp near Ballymahon.

The column stayed in the Summerhill area for over a fortnight where Tormey utilised his British Army expertise to put it through a training course. Emboldened by their earlier success and not wanting to rest on their laurels, the Volunteers set up three ambush positions in succession for RIC cycle patrols, only for none to show. Skirting Athlone on its Connaught side, the column packed up and crossed the Shannon, aiming to set up camp near Ballymahon.

Belatedly deciding that discretion was the better part of valour, Tormey initiated a retreat, being the first into a ditch behind the ambush site. There he was shot in the head before he could realise he had been outflanked. Some of the RIC had edged down a lane that ran at right angles to the site, an opening the IRA had neglected to watch, from where they opened fire to surprise their ambushers in turn.

Belatedly deciding that discretion was the better part of valour, Tormey initiated a retreat, being the first into a ditch behind the ambush site. There he was shot in the head before he could realise he had been outflanked. Some of the RIC had edged down a lane that ran at right angles to the site, an opening the IRA had neglected to watch, from where they opened fire to surprise their ambushers in turn.

Despite O’Meara continuing on as an active Volunteer, there is a dearth of much further activity in his BMH Statement. When the Truce came into effect, he attended an IRA officers’ training camp where he was faced with the choice of taking up soldiering on a professional basis in an army that was to be restructured on regular lines or to return to the business he had neglected. O’Meara decided on the latter. Reading between the lines of O’Meara’s Statement, one can detect an air of exhaustion after all the work he had done and for very little reward or gratitude.

Despite O’Meara continuing on as an active Volunteer, there is a dearth of much further activity in his BMH Statement. When the Truce came into effect, he attended an IRA officers’ training camp where he was faced with the choice of taking up soldiering on a professional basis in an army that was to be restructured on regular lines or to return to the business he had neglected. O’Meara decided on the latter. Reading between the lines of O’Meara’s Statement, one can detect an air of exhaustion after all the work he had done and for very little reward or gratitude.

This exodus from the RIC prompted the Ballymore Council to pass a resolution at its monthly meeting on 19th August 1920, congratulating the policemen who had resigned. Its following resolution was telling: an agreement to strike a rate of pay for the upkeep of the Irish Volunteers, or the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as the organisation had renamed itself. After all, it was the IRA, not the RIC, who were now performing the policing duties in Ballymore as well as the rest of Co. Westmeath.

This exodus from the RIC prompted the Ballymore Council to pass a resolution at its monthly meeting on 19th August 1920, congratulating the policemen who had resigned. Its following resolution was telling: an agreement to strike a rate of pay for the upkeep of the Irish Volunteers, or the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as the organisation had renamed itself. After all, it was the IRA, not the RIC, who were now performing the policing duties in Ballymore as well as the rest of Co. Westmeath.

It was not until mid-1920 that operations against RIC barracks by the Athlone Brigade were actually implemented. Even then, the majority of these were after their garrisons had been evacuated, making their destruction a relatively easy accomplishment.

It was not until mid-1920 that operations against RIC barracks by the Athlone Brigade were actually implemented. Even then, the majority of these were after their garrisons had been evacuated, making their destruction a relatively easy accomplishment.