Do personalities shape politics or does the political world move with a will of its own? Can individuals determine the fate of nations or are even the most powerful of statesmen doomed to be swept up by events? These are the central questions of this book, as historian Alvin Jackson looks at two men, John Redmond and Edward Carson, of very different natures, who stood on opposite sides at the heart of one of the most turbulent periods in Anglo-Irish history.

Do personalities shape politics or does the political world move with a will of its own? Can individuals determine the fate of nations or are even the most powerful of statesmen doomed to be swept up by events? These are the central questions of this book, as historian Alvin Jackson looks at two men, John Redmond and Edward Carson, of very different natures, who stood on opposite sides at the heart of one of the most turbulent periods in Anglo-Irish history.

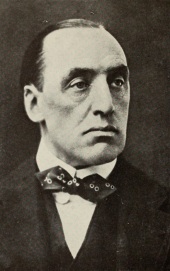

An interview each with Lord Kitchener on the eve of the Great War in 1914 best exemplified their contrasting styles. Both Carson and Redmond had placed the militias under their influence – the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Irish Volunteers respectively – at the behest of the War Office in return for certain concessions. Such horse-trading stuck in the craw of the martinet Kitchener who, as the Secretary of State for War, lost no time in attempting to cut the uppity Irishmen down to size.

“If I had been on a platform with you and Redmond, I should have knocked your heads together,” Kitchener told Carson.

“I’d like to see you try,” replied the other. This was delivered, according to one account, “in a slow drawling way, but with such a look as made Kitchener instantly change his tone.”

Redmond, on the other hand, chose to stand on his wounded dignity. He had been, as he wrote to the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, after his own bruising encounter with Kitchener, “rather disquieted” by it. Nothing stronger was done or said.

Perhaps not coincidently, it was decided that the Ulster Volunteer Force could keep its identity within a separate army division. No such allowance was made for the Irish Volunteers.

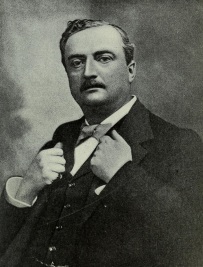

But then, not rocking the boat had defined Redmond’s leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) ever since his election as a compromise candidate. It had been a turbulent decade for Nationalist Ireland in the wake of the Parnell Split of 1890, and it was thus fitting that the reunion of the IPP factions be conducted in as acrimonious manner as possible. As summed up by Jackson, Redmond’s elevation was decided by the Party bigwigs narrowing down to who was despised the least:

Tim Healy, believing that [John] Dillon preferred T.C. Harrington, and hating Dillon more than Redmond, had conspired to deliver the latter’s victory in 1900, while at the same time fully expecting him to lose: he regarded Redmond’s final election as simply a ‘fluke’, partly because at the last minute and unexpectedly, William O’Brien had intervened to offer his backing.

Redmond never forgot the tenuity of his authority, nor the underlying tensions it guarded over. “My chief anxiety ever since I have been Chairman of the Irish Party has been to preserve its unity,” he said – more than seven years later. Even an admirer of Redmond’s “impressive manner” could not help but wince at his “non-committal introductory address, which gave him a loophole of escape in every sentence.”

Following in the footsteps of Charles Parnell as the ‘Uncrowned King of Ireland’ was always going to be a tall order, but Redmond never really tried. When he described himself as the “servant of the Irish Party…I have never attempted in the smallest manner to impose my will upon the will of the Irish Party,” he was that rarest of creatures – an honest politician.

Honed by years of bare-knuckle courtroom drama, where he had excelled as a barrister, Carson presented a very different political beast. For one, unlike Redmond, he was not afraid to bite the hand that fed him. As MP for Dublin University (Trinity College), Carson took the lead in opposing the reforms of the Irish Land Bill of 1896, acting on behalf of his conservatively-minded constituents.

This was despite the fact that the bill was the brainchild of the brothers Arthur and Gerald Balfour. The latter, as Chief Secretary of Ireland from 1887 to 1891, had pushed for Carson’s advancement in the legal profession and then later his election to MP. Balfour was all too aware of this twisted turn of events, as he complained plaintively in the wake of a tongue-lashing from his former protégé:

Carson was the aggressor and made an entirely unprovoked attack. He had a perfect right to forget that I had promoted him above the heads of all his seniors to the highest place at the Irish bar, and that I had strained my influence…with Trinity College Dublin to get them, for the first time in their history, to elect as their representative one who then called himself a Liberal…But he had not the right to forget that we belonged to the same party and that as colleagues under most difficult and anxious circumstances we had fought side-by-side in many a doubtful battle.

For Carson, it was a case of putting principle before party, with personal friendships taking second place to whatever cause for which he was advocate.

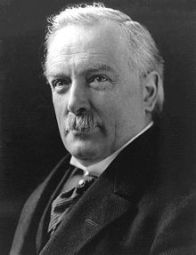

Such prioritising made him a most mercurial ally. After serving a mere five months as attorney general in Asquith’s wartime government, he resigned in October 1915 and became an implacable opponent to the Prime Minister, pursuing him with the same doggedness he displayed in a courtroom until Asquith’s resignation at the end of 1916, a move largely accredited by Westminster insiders to Carson.

If Redmond lacked such a killer instinct, he compensated with an even temperament that allowed him to manage the complex and far-ranging responsibilities as IPP chairman. “Patient, careful, consensual – but occasionally capable to the necessary anger – he held together, from a position of weakness, this great national enterprise, and brought it to the cusp of victory in 1914,” Jackson writes.

Carson, in contrast, was on unsteady ground when not on the offensive. Having orchestrated Asquith’s fall and his replacement by David Lloyd George, Carson was promoted by the new prime minister to the Admiralty, a role in which he proved to be – so to speak – lost at sea.

German submarines were reaping a devastating toll on British shipping, yet Carson had no ideas to offer a dispirited navy. It took a vigorous intervention by Lloyd George in August 1917, when he harangued the Admiralty Board from – tellingly enough – Carson’s seat at the table, to kick-start a more proactive policy. Carson was soon shuffled off to a harmless post elsewhere.

Jackson takes a surgical approach to his material, prising open the public personae of Carson and Redmond to find the complexities and contradictions beneath. At times he seems to enjoy teasing the boundaries of what we know – or think we do – about the two men. “Would a Carsonite leadership of the Irish Party have produced a different fate for constitutional nationalism?” he asks. “Would a more senatorial and oritund command of Ulster unionism have sustained a militant defiance of the British Government?” The pair, Jackson suggests, each had the right abilities for the wrong position.

On a lighter note are the range of documents and memorandum on display here. They vary from satirical cartoons and political posters, to a postcard featuring Redmond’s pensive visage on one side and on the other a written comment from an appreciative – and apparently Unionist – woman: “Is not this photo nice. Though of wrong party, I would like to elope with him.”

Publisher’s Website: Royal Irish Academy