Who?

The Robert Emmet Commemoration Concert was announced for the 4th March 1919, to be held in the Mansion House, Dublin. Posters advertised the event with the promise of a special – but unnamed – star attraction:

AN ADDRESS WILL BE GIVEN BY

A PROMINENT REPUBLICAN LEADER.

WHO?

The concert organisers played their cards close to their chests, letting only a select few know the identity of the mystery guest. After the first part of the performance, it was announced by Diarmuid O’Hegarty that the promised oration was about to commence in the Round Room, to be presided over by Seán Ó Muirthile.

That both O’Hegarty and Ó Muirthile were high-ranking members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the secret society dedicated to freedom for Ireland, was no coincidence. This was to be more than a celebration of a long-dead patriot but a defiant clenching of the fist by living ones.

Even if unaware of all this, the guests could not have failed to note the presence of the Irish Volunteers, acting as stewards for the event. Some of them had been ordered to carry revolvers, although presumably not openly, this being an event to enjoy, after all.

As the advertised ‘prominent Republican leader’ prepared to make his entrance, Volunteers took up duty by the doors. One of them, Michael Lynch, remembered the anticipation:

One could feel the air of expectancy in the vast audience. From the supper-room, at the rere [sic] of the round room, came the sound of a pipers’ band tuning up. After a few minutes, the doors of the supper-room were thrown open and the pipers’ band came in, making a most infernal noise.[1]

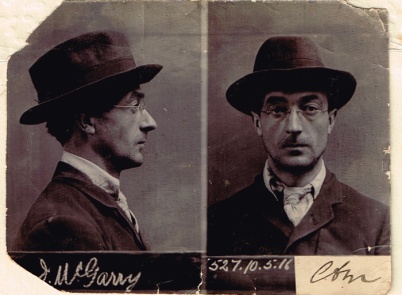

In the middle of the band, dressed in the uniform of the Irish Volunteers, was Seán McGarry. As soon as he was recognised, the crowd broke out into a rapturous outburst of cheers, clapping and whistling loud enough to drown out the ‘infernal noise’ of the band. For who could fail to appreciate the pluck and daring of the man who had, along with others, broken out of an English jail a mere month and a day ago?

Ability, Tact and Discretion

McGarry walked on stage “rather shyly,” according to Lynch, understandably so, given the attention being heaped on him. Sharing the platform was Ó Muirthile and the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Laurence O’Neill, bedecked in his chain of office. There the three of them stood for many minutes until the cheering had died down enough for Ó Muirthile to begin.

He introduced McGarry – rather unnecessarily by this point – and said that if the true story of his escape was told, it would shatter all the ones they had been reading in the newspapers.

“At any rate,” Ó Muirthile continued, “he is here, and he has not been brought here by any of the methods that have been described in the Press for the past few days. He is here, owing in the ability, tact, and discretion of the men who are leading the Irish Republican Army.”

Then it was the turn of the Lord Mayor. He stood before them, he said, in the full adornment of his office to honour this latest fugitive from British injustice. He was there because a solemn and imperative duty demanded him to be there, first to tender a hearty welcome to his colleague, Councillor Seán McGarry, to the Mansion House.

And he was there to show his utter contempt, a contempt which was shared in every liberty-loving man and woman the whole world over, for a Government which detained in English jails so many of his fellow countrymen without any trial, without any charge, at the expense of the fundamental principles of liberty, justice and fair play.

(O’Neill was far less amenable when he wrote about the event several years later. He had worn his chain of office in honour of Robert Emmet, not McGarry whose appearance had been sprung on him at the last second. A consummate professional, O’Neill had nonetheless carried on with the show.)

Homecoming

Now it was finally time for McGarry to deliver his much hyped oration. What it was, Lynch could not recall, not that it mattered much. It was enough for McGarry to have appeared in public and give lie to the claims of the British Government that not one of its former prisoners had made it back to Ireland.

Whatever McGarry said, it was received with “great enthusiasm,” according to the Irish Times. The Irish Independent said even less, reporting in detail on Ó Muirthile’s and O’Neill’s words but nothing about McGarry speaking at all. For all the stir he caused, McGarry emerged from his own performance as little more than a prop for a piece of theatre.

But then, perhaps as Lynch suggested, it did not matter all that much in the end.

The Volunteers on the doors were ordered to bar everyone from leaving or using the phones while the speeches were going on. Trust was evidently a limited commodity. The Lord Mayor was among those blocked but made light of the inconvenience, quipping that he could not move in his own house.

As soon as McGarry was done, he was whisked out of the building by an escort of Volunteers and taken to Molesworth Street where a car was waiting, not to mention a large force of policemen and detectives, no doubt alerted by the gathering nearby. Nonetheless, perhaps deterred by the bodyguards, the police did not interfere as McGarry was taken to the car and driven away. The Volunteers returned to the concert which, by all accounts, continued to be a great success.[2]

The Men Behind the Man

Seán McGarry was no newcomer to Irish Republicanism. Born in 1886, in Dundrum, Co. Dublin, the son of a letter carrier, he worked as an electrician while a key operative in the planning of the Howth gunrunning and then later the Easter Rising.

Unfortunately, he wrote no memoir and gave little about himself in his Bureau of Military History (BMH) Statement (leaving it to others to tease out some details on his activities), preferring instead to focus on his mentor within the IRB, Tom Clarke.

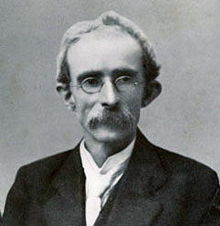

McGarry first met the veteran Fenian in 1907 shortly after the latter’s return to Ireland. He was to provide no details on the circumstances – as if the years spent in the shadows and silences of a secret society had sapped his ability to be too forthcoming – only that he had been expecting a venerable elder, aged by many years in prison but finding instead one with the demeanour and enthusiasm of someone much younger. McGarry quickly became one of Clarke’s staunchest followers, a “right-hand man” in the words of another IRB member.[3]

Another IRB organiser to whom McGarry was close was Seán Mac Diarmada. They had known each other since 1906-7 when they had belonged to the Dungannon Club in Belfast, one of the few times McGarry ventured out of the Dublin orbit.[4]

In general, McGarry served as a go-between and emissary. The future Chief Justice of Ireland, Tim Sullivan, received a visit from McGarry in 1915 while the former was working as a barrister. McGarry had been sent by Mac Diarmada on behalf of a Volunteer arrested for illegal possession of arms and explosives.

As instructed, McGarry offered Sullivan a hundred guineas on his brief. Sullivan stared hard at his visitor, saying: “In my opinion, you boys are Fenians.”

True to his membership of a secret society, McGarry said nothing. Correctly taking the silence as an assent, Sullivan then agreed to take on the case, waiving aside his usual fee (the defendant was later acquitted).[5]

A Day Out in Howth

On the 25th July 1914, a message was sent to several IRB initiates (who doubled as Irish Volunteers) to meet McGarry that day at Nelson’s Pillar. None of the four men who came knew what was to be expected of them but waited all the same until McGarry arrived. When the others inquired further, he politely told them to mind their own business.

The group drove to Amiens Street Station where McGarry purchased five tickets for Howth. They arrived in the harbour at 4 pm, where McGarry told them to go to the end of the East Pier while he waited by the station. The four others did so, and McGarry later rejoined then at the Pier, accompanied by a middle-aged fisherman in a blue jersey and a peaked cap.

The hoary sea dog bluntly told them that their request to do a spot of fishing was impossible given the rough weather. After some arguing on the matter, McGarry walked away with the fisherman, still arguing, but it seems to have been resolved when McGarry returned to the others after a short while. If he could get a boat, he asked them, would they be willing to venture out on it – a reasonable question as it was raining hard with high winds and rough waters.

Undeterred, the men voiced their assent. McGarry finally told them what was going on – they were to go out and make contact with a boat laden with weapons. This came as no huge surprise as the men had been hearing rumours about the importation of guns for some months now.

‘A Beautiful Sight’

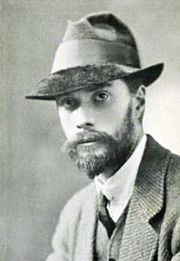

McGarry then left again after telling them to stay put until further instructions. Two hours later, the men were surprised to see Darrell Figgis, the writer (and, unknown to them, one of the chief organisers of the gunrunning), coming down the pier with the same fisherman as before, the pair of them walking up and down the boards in a fresh argument.

McGarry arrived back on the scene, accompanied by Clarke, in time to join in the argument with Figgis and the stubborn fisherman. Finally, McGarry told the waiting team to remain where they were on the pier while he attempted to make alternative arrangements for a boat, possibly from Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) on the other side of the bay. The fisherman was apparently not to be moved.

The four men remained by the sea, depressed at the seemingly wasted day. A messenger came on a bicycle at 9 pm, five hours after they had arrived, only to tell them to keep waiting. The last tram and train had left Howth for the night by the time a second cyclist arrived to inform them they could return to the city but to stick together. Soaked to the skin from the rain, the men trudged back inland.[6]

McGarry drove with Figgis to Kingstown, hoping to catch the yacht, Asgard, loaded with the promised armaments from there. They sighted the vessel over the water but, lacking anyone like they had in Howth, the pair had no choice but to finally retire, weary and disheartened, to the Marine Hotel at 4 am for a few hours of sleep.

Returning to Howth on the first train that morning, McGarry and Figgis met a second team from Bray, which were posted at the base of the north pier. By 9:30 am the Asgard could be seen on the far side of Lambay Island but, as it approached the pier, there was no sign of any other Volunteers to assist. It was only when the yacht drew next to the pier-head that Figgis heard McGarry beside him say: “Here they are; look at them, aren’t they a beautiful sight.”

A column of Volunteers were marching towards them, including the four who had been with McGarry in Howth the day before. All were ready and eager to assist in the unloading of the arms in what would become known to history as the Howth gunrunning. It had been touch-and-go, but the efforts of McGarry, Clarke, Figgis and the Irish Volunteers had finally paid off.[7]

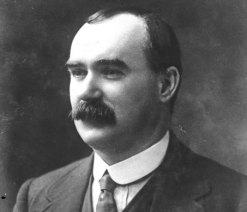

Meeting Connolly

McGarry was among those assembled in the library of the Gaelic League headquarters in Parnell Square in September 1914 when Clarke and MacDermott announced their intentions of starting an armed uprising at an opportune time. Also present were James Connolly, Arthur Griffith, Seán T. O’Kelly, Patrick Pearse, Thomas Mac Donagh and Joseph Mary Plunkett, many of whom would help spearhead the Rising. Given how close McGarry was to both Clarke and Mac Diarmada, the news could hardly have come as a surprise to him.[8]

Sometimes afterwards, McGarry called on Liberty Hall, the ostensible reason to ask Connolly for an article on the Irish Citizen Army (presumably for the Irish Freedom, the IRB organ that he and Mac Diarmada worked on). The two had been on friendly terms for a number of years, McGarry having given Connolly a weekly article during the Dublin Lockout of 1913 in a gesture of solidary.

As McGarry was editor of the Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa funeral souvenir booklet (in addition to the other hats he wore in service to the cause), the topic of conversation turned to that of the deceased Fenian.

“What’s the good of talking about Rossa?” Connolly asked, according to McGarry’s recollections in his BHM Statement. “Rossa wanted to fight England when England was at peace. You fellows want to fight when she is at war.”

When McGarry finally departed from Liberty Hall, it was with a promise from Connolly that the latter would provide the sought-after article. In return, McGarry would talk with him further. After McGarry had passed onto Clarke what he and Connolly had talked about, Clarke paid Liberty Hall a visit of his own. Shortly afterwards Connolly became the newest member of their budding cell. Although McGarry did not say no explicitly in his BMH Statement, it is clear that he was used to ‘feel out’ Connolly, who was at that point an outsider to the planning and an unknown factor needing to be brought into the fold.[9]

McGarry would later publicly describe Connolly as “the man who…taught me to be a Republican.” Republicanism from a different angle, perhaps, but Republicanism all the same. In private, however, he remembered Connolly as a man of great courage and intelligence but also one who was headstrong, naïve and easily manipulated by the far wilier Clarke. For all his extravagant praise of the socialist, it was the Fenian who truly taught McGarry how to be a Republican.[10]

Bumps on the Road

Preparations for an uprising continued, although not always smoothly. “It’s all right, Tom, it’s not loaded,” McGarry told Clarke as he playfully pointed a pistol at him, near the end of January 1916.

Both men were given an impromptu lesson in firearms safety when the supposedly safe gun went off and hit Clarke in the elbow. The bullet was surreptitiously removed, along with stray bone fragments, at the Mater Hospital the next morning. Clarke never recovered full use of his wounded right arm, forcing him to learn how to use a revolver with his left hand in time for the Rising in April, though he was magnanimous enough not to hold it against McGarry.[11]

On a more positive note, Mac Diarmada visited McGarry in a jolly mood on the 19th April, five days before the start, telling him that Eoin MacNeill, the Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers and reluctant ally to the IRB, had “agreed to everything” in regards to the planned uprising.[12]

MacNeill, however, would turn out to be not as agreeable as believed.

McGarry was making his way back home from Mass on the morning of the 23rd, having stayed the night with Clarke, when he read in the press MacNeill’s orders to cancel the planned rising. McGarry walked home in a daze to find Michael Collins, having come over for breakfast. The two ate in dumbstruck silence after McGarry showed Collins the newspaper, and then they left for Liberty Hall where the IRB Military Council was struggling to comprehend the new development.

McGarry found Clarke who, for the first time since he had known him, appeared tired and crestfallen. The two walked in silence to Clarke’s home where the older man was recovered enough to lambaste MacNeill’s actions as the vilest of treacheries. When it came to addressing the subject for his BMH Statement, McGarry preferred to adopt a tone of dignified, if somewhat disdainful silence:

I do not propose to go into the pros and cons of the matter. Reams of paper have been covered with mostly ill-informed statements and speculations and other reams are I am told written for later publications. And so I leave it.[13]

Such pros and cons, statements and speculations, were to be merely academic. Countermanding orders or no, the Rising was going ahead. Clarke was sure on that, and McGarry would be at his side for it as always.

Easter Monday

James Rowan, a 15-year old telegraph messenger, was idling away time in the delivery room of the General Post Office (GPO) on the morning of the 24th April when the policeman on duty came in, wanting to use the phones there to contact his superiors, having just been disarmed by Irish Volunteers.

The phones were found to be out of order. Looking out of the rear window of the delivery room, Rowan and the other staff saw the rest of their colleagues and some British soldiers, also disarmed, being marshalled out into the yard. The delivery room occupants stayed where they were but when they heard a rousing cheer, the Inspector in charge risked opening the door for a peek outside.

“Quick, look at what these fellows are doing,” the Inspector called to the rest. Rowan joined him to see a cab had pulled up outside in Princes Street North, next to the GPO. Volunteers were hard at work, either smashing the windows of buildings with the butts of their rifles or lifting boxes of ammunition from the cab to hand to their comrades through the broken windows.

A stern voice demanded that the Inspector hand over his keys. The speaker emerged from the blind side of the door, holding a revolver, and Rowan saw a glimpse of a face with horn-rimmed glasses before he retreated back inside:

That face was photographed in my mind…The demander of the keys I recognised after the Rebellion from photographs in the papers giving particulars of those who had been arrested and identified as being prominently associated with the movement. He was Sean McGarry, who may be able to confirm the account of this incident.

The Inspector wisely complied and threw his keys onto the footpath. The door was slammed shut, locking the occupants in before they were released by the Volunteers later that afternoon.[14]

Culmination

McGarry left the GPO on Monday evening to take command of the Radio Transmitting Station in Lower Sackville (now O’Connell) Street. He returned in time to lead a hunt for supplies on a jewellery store at the corner of Abbey Street (three pairs of binoculars and some watches were found and taken).[15]

For the most part, however, McGarry remained in the post office with Clarke. He was to provide his BMH Statement with little about his activities during the fighting, pleading poor memory:

I have little to say about Easter Week. I have a very clear recollection of all that happened within my observation but after Tuesday I cannot for the life of me separate the days.[16]

Nonetheless, he remembered enough to take the time in his BMH Statement to correct a passage in Frank O’Connor’s biography, The Big Fellow, about Clarke losing his cool under pressure. McGarry insisted that Clarke had remained resolute and determined (evidently a well-read man, McGarry also took the Breton writer Louis le Roux to task for some unflattering remarks in the latter’s book on Clarke).[17]

On Thursday, the 27th, McGarry was part of a team sent over to the offices of the Freeman’s Journal on the other side of Princes Street North from the GPO. While crossing the street, the party came under fire, with McGarry narrowly avoiding becoming a casualty. Having arrived unscathed, the men broke through the walls of the office to the neighbouring building. The need for an escape route was rapidly becoming an acute one but when the GPO was evacuated the next day, it was in the opposite direction, to Moore Street.[18]

McGarry was one of the last to leave the post office, ensuring that the building was clear as per Clarke’s orders. He had already eaten a last meal of mutton chops with Clarke, Mac Diarmada and several others. The mood was a resolutely jolly one, McGarry jokingly asking if he would go to Hell for eating meat on this particular Friday.

After the withdrawal, it took a while for McGarry to find Clarke again in Moore Street. Clarke and MacDermott were discussing the possibility of surrender, the former dolefully quiet, the latter close to tears.

McGarry felt too drained to contribute a word to the discussion. Only recently he had been weighing up the odds with a wounded and bedridden Connolly for a successful counterattack on British-held barricades, and now it had come to this. While the negotiations to surrender were on, Clarke, seconded by Mac Diarmada, gave permission for the rest to escape. Though McGarry passed this on to others, he remained where he was, committed to the cause and the event he had helped set in motion.[19]

After the Rising

After the surrender, McGarry was led away by British soldiers to Richmond Barracks along with Clarke and others. En route, Clarke was able to pass on a hastily scribbled note to his wife, via an obliging British soldier. The letter expressed his pride in the Rising and the men who had helped him carry it out: “Sean [Mac Diarmada] is with me and McG [McGarry] – They are all heroes.”[20]

Upon reaching the barracks, McGarry was observed being picked out by police officers along with the other leaders such as Clarke, Joseph Mary Plunkett and Mac Diarmada in a backhanded tribute to his importance.[21]

As Prisoner #28, McGarry was court-martialled in a batch of four that included Willie Pearse. All but Pearse pleaded not guilty. McGarry’s defence that he had known nothing about anything until the occupation of the GPO, after which he had been only a messenger with no position or rank of any kind, belied his true role behind the scenes.

His defence must have been convincing. Though all four prisoners were found ‘Guilty. Death’, McGarry was singled out for a recommendation of mercy on the grounds that he had been “misled by the leaders” of the Rising. He was sentenced instead to eight years of penal servitude.[22]

So quickly had the court-martial been held that prisoners were still arriving in Richmond Barracks. There was some astonishment at the extent of the sentence, although it was a far lighter sentence than Clarke’s, who McGarry saw for the last time on the day before his mentor’s execution.[23]

Continued by: Twenty Years a Republican: The Trials and Tribulations of Seán McGarry, 1919-1922 (Part II)

Sources

[1] Lynch, Michael (BMH / WS 511), p. 94

[2] Lynch, pp. 94-5 ; Kelly, Patrick J. (BMH / WS 781), pp. 49-50 ; Irish Times, Irish Independent 05/03/1919 ; Morrissey., Thomas J. Lord Mayor of Dublin (1917–1924), Patriot and Man of Peace (Dublin: Dublin City Council, 2014), p. 144

[3] McGarry, Seán (BMH / WS 368), p. 26 ; biographical details from White, Laurence William, ‘McGarry, Seán’ (1886-1958) Dictionary of Irish Biography (Royal Irish Academy, general editor McGuire, James) ; Gleeson, Joseph (BMH / WS 367), p. 8

[4] Braniff, Daniel (BMH / WS 222), p. 2

[5] Sullivan, Mrs. T.M. (BMH / WS 653), p. 3

[6] Daly, Seamus (BMH / WS 360), pp. 8-10

[7] Figgis, Darrell. Recollections of the Irish War (New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., [1927?]), pp. 45-7

[8] Ó Broin, Leon. Revolutionary underground: the story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillian, 1976), p. 156

[9] McGarry, p. 21

[10] Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922, 06/01/1921, p. 211. Available from the National Library of Ireland, also online from the University of Cork: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/E900003-001.html ; McGarry, pp. 21-2

[11] Litton, Helen. 16 Lives: Thomas Clarke (Dublin: The O’Brien Press, 2014), p. 150

[12] McGarry, p. 23

[13] Ibid, p. 24

[14] Rowan, James (BMH / WS 871), pp. 2-3

[15] O’Reilly, Michael William (BMH / WS 886), p. 7 ; Daly, William D. (BMH / WS 291), p. 18

[16] McGarry, p. 24

[17] Ibid, pp. 5-6, 25

[18] Gleeson, p. 10

[19] Ibid, pp. 25-6 ; Dore, Eamon T. (BMH / WS 392), pp. 18-19

[20] Barton, Brian, The Secret Court Martial Records of the Easter Rising (Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2010), p. 155

[21] Henderson, Frank (ed. by Hopkinson, Michael) Frank Henderson’s Easter Rising: Recollections of a Dublin Volunteer (Cork: Cork University Press, 1998), p. 69

[22] Barton, pp. 180-1 ; Irish Times, 10/12/1958

[23] Cosgrave, Liam T. (BMH / WS 268), p. 8 ; McGarry, p. 26

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History Statements

Braniff, Daniel, WS 222

Cosgrave, Liam T., 268

Daly, Seamus, WS 360

Daly, William D., WS 291

Dore, Eamon T., WS 392

Gleeson, Joseph, WS 367

Henderson, Frank, 821

Kelly, Patrick J., WS 781

Lynch, Michael, WS 511

McGarry, Seán, WS 368

O’Reilly, Michael William, WS 886

Rowan, James, 871

Sullivan, Mrs. T.M., WS 653

Books

Barton, Brian. The Secret Court Martial Records of the Easter Rising (Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2010)

Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922. Available from the National Library of Ireland, also online: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/E900003-001.html

De Burca, Padraig and Boyle, John F., Free state or republic?: Pen pictures of the historic treaty session of Dáil Éireann (Dublin: The Talbot Press, 1922)

Figgis, Darrell. Recollections of the Irish War (New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., [1927?])

Henderson, Frank (ed. by Hopkinson, Michael) Frank Henderson’s Easter Rising: Recollections of a Dublin Volunteer (Cork: Cork University Press, 1998)

Litton, Helen. 16 Lives: Thomas Clarke (Dublin: The O’Brien Press, 2014)

Morrissey, Thomas J. Lord Mayor of Dublin (1917–1924), Patriot and Man of Peace (Dublin: Dublin City Council, 2014)

Ó Broin, Leon. Revolutionary underground: the story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillian, 1976)

White, Laurence William, ‘McGarry, Seán’ (1886-1958) Dictionary of Irish Biography (Royal Irish Academy, general editor McGuire, James)

Newspapers

Irish Independent

Irish Times