A continuation of: Out of the Bastille: Rory O’Connor and the War of Independence, 1918-1921 (Part II)

Plans and Pitfalls

Joseph Lawless was a busy man in his workshop at 198 Parnell Street, Dublin, where he churned out bombs for use by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The process was a simple one: a steel pipe sawn off to four inches and then sealed at either end, save for a hole drilled in one in which to insert the fuse. But this was too crude a method for Lawless’ exacting standards and so he argued to colleagues that his allocated funds would be better spent renovating the old foundry in the basement. With that, a more sophisticated type of explosive could be produced.

His lobbying was successful enough for a visit to the workshop from Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, the O/C and the Quartermaster of the Dublin IRA Brigade respectively. The two officers listened as Lawless expounded on his proposal. While interested, McKee remained noncommittal, telling Lawless that he would send over Rory O’Connor, the Director of Engineering in the IRA GHQ, for a second opinion on the idea’s feasibility.

The man in question called in at the workshop a day or so later. Lawless’ first impression was not a promising one:

He struck me as peculiarly solemn and unsmiling, one might say lugubrious, and did not appear to listen to what I said when I began to explain the details of what I considered my plan for a bomb factory.

Where was the furnace? O’Connor asked Lawless while the latter was in mid-sentence. He wanted to examine it for himself.

Lawless took his graceless guest down to the basement, cautioning him that the furnace, in an unlit corner at the back, was missing the grating for its draught-pit in front. Ignoring this advice, O’Connor pressed on in the dark and, before Lawless could stop him, stumbled into the open hole, much to Lawless’ quiet amusement.

Still, no harm done save to O’Connor’s dignity and, after a few days, Lawless received word that his proposal had been approved by his Brigade superiors. O’Connor had evidently submitted a favourable report on his findings, however gauche he might have been in person.[1]

Different Impressions

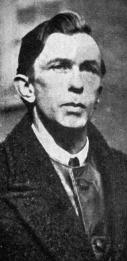

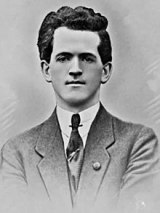

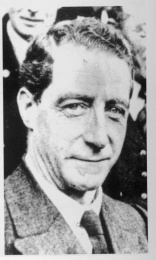

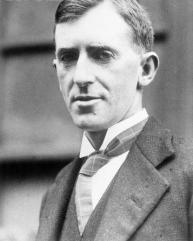

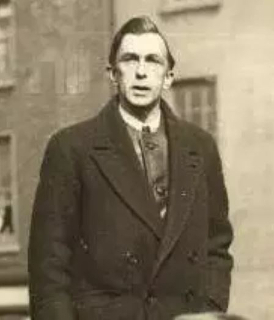

O’Connor could have that effect on his fellow revolutionaries. Todd Andrews thought him “too forbidding a person to approach. He was saturnine in appearance, very dark-skinned, always in deep thought, brooding and worried. He did not look a healthy man.” But to Piaras Béaslaí, while he conceded that O’Connor’s “manner was not attractive to strangers…those who were intimate with him found him to be a very pleasant and sociable companion.”[2]

Another one close enough to uncover O’Connor’s inner charm was David Neligan. “He was good company, a great talker, very cheerful,” Neligan remembered. Though he shared O’Connor’s political convictions, his role in the Irish struggle was a very different one: as a senior officer in the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), Neligan had access to confidential information in Dublin Castle, which he leaked to his IRA contacts. He was walking through St Stephen’s Green with a DMP co-worker when the latter indicated a short, middle-aged man, with a face thin to the point of haggard, sitting nearby on a park bench.

“See him, Dave?” said the policeman. “He is a prominent Sinn Feiner. If he is there tomorrow, we’ll have him pulled.”

Having recognised O’Connor, Neligan made sure to pass on a warning, much to O’Connor’s gratitude. Though O’Connor had dodged arrest, Neligan was to see him in peril again, this time in the yard of Dublin Castle, being interrogated by a British intelligence officer. Neligan tried arguing that the suspect was merely a harmless eccentric but to no avail.

“I’m told,” said the officer, “that he is a prominent Shinner.”[3]

Which was true enough, and O’Connor was forwarded to Arbour Hill to join the other POWs there, including Lawless, who had likewise been collared. As if that was not bad enough. Lawless learnt the day after his apprehension, in December 1920, about the discovery of his Parnell Street workshop and the bomb-factory he had worked so hard to set up.

It was not the end of the war, of course, nor of Lawless’ part in it, and he handled the smuggling of letters in and out of Arbour Hill, thanks to bribed wardens. Through this, O’Connor was able to keep in contact with the rest of the revolutionary leadership, though there was something about O’Connor that Lawless found unsettling.

According to Lawless, it was an opinion shared by a number of the other inmates:

Rory was a solemn, unsmiling egotistical sort of person whom we looked upon as a little mad and did not take him too seriously.

At least the authority of Con O’Donovan helped keep things steady. As the elected commandant of the prisoners, O’Donovan liaised with the Arbour Hill governor and ensured the maintenance of discipline among the inmates. Near the end of January 1921, O’Donovan was transferred to Ballykinlar Camp, an internment centre set up to manage the overflow of captives taken by the Crown forces as the war intensified.

O’Donovan’s absence created a vacancy for the role of prison commandant, which Lawless was voted in to fill. Not all were pleased by this choice, however, as Lawless recalled:

The other candidate for the appointment was Rory O’Connor, who mooted around the claim that as a member of the IRA General Staff he was the senior officer in the prison. However, as I have already mentioned, the general body of prisoners did not quite trust Rory’s mental balance.

To smooth things over, Lawless pointed out to O’Connor that it was best for him not to gain too much prominence and instead remain anonymous among the mass of detainees. Despite his capture, O’Connor’s identity and true importance was unknown to his captors, who registered him under the assumed name he had provided.[4]

Prison Pump Politics

O’Connor made no more complaints over who was what, though Lawless did not think he was entirely conciliated. In early March 1921, the inmates were paraded in the main hall, where the names of those due to be moved to the Curragh, Co. Kildare, were read out, around one hundred and fifty, which amounted to half their number.

Lawless and O’Connor were among those set to leave. While they waited, listening to the hum of the vehicles outside that were to be their transport, O’Connor sidled up to Lawless and asked in a whisper if he had any plans to escape along the way. To O’Connor’s displeasure, Lawless told him no, not for the moment, since they were sure to be heavily guarded, unless an opportunity happened to appear.

This wait-and-see attitude was not what O’Connor had been wanting to hear:

He then took up the heavy attitude with me and, speaking as a member of the General Staff, warned me that it was my duty as a prisoners’ commandant to organise an escape. Poor Rory was evidently still suffering from the snub to his dignity of my election as commandant against his candidature, and I regretted the necessity for a further snub when I replied that the matter rested safely in my hands.

Lawless at least refrained from the ‘snub’ of saying that he was less concerned about the journey ahead – he did not think much was likely to happen on the road – and more about O’Connor, who Lawless was sure would make another attempt at the position of commandant once they were in the Curragh. Not that Lawless desired leadership and its responsibilities but he wanted O’Connor in control even less.

Once he separated himself from O’Connor, he went to Peadar McMahon, a friend of his, and persuaded him to put himself forward for the role once they reached the Curragh. McMahon reluctantly agreed to do so but only on condition that Lawless would help shoulder the burden.

“All this may sound a bit like parish pump politics,” Lawless admitted when composing his account for posterity. Eager to avoid factions, he hoped that McMahon would be a unanimous choice…anyone would do, in fact, as long as it was not O’Connor.[5]

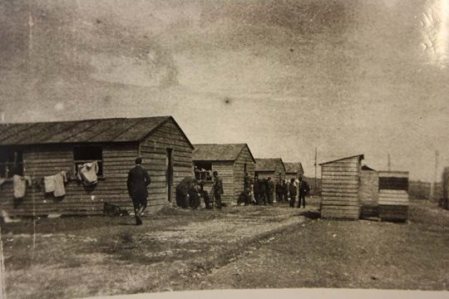

In that, Lawless had his way. McMahon was elected to be in charge for the duration of their stay in the Curragh, with Lawless his second-in-command as agreed. O’Connor had been outmanoeuvred, and Lawless prepared to make do as best he could to life behind the barbed wire-fences and sentry-points of the Rath Camp. Their new confinement was a circular mound, with a diameter of a hundred feet, which lay on a ridge just west of the Curragh. Rebels of a past generation had surrendered there in 1798, only for Crown forces to break the terms and massacre them.

Whether or not their captors knew of the site’s historical significance, it was a bleakly fitting place to store the latest crop of subversives. A city boy, Lawless was discomforted by the wide plains that stretched to the distant horizon whenever he looked outside his confinement, as well as awed at the British military strength on display elsewhere in the Curragh.[6]

When peace presented itself in the form of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921, Lawless seized the chance. His acceptance of the controversial terms put him at odds with certain individuals, though this, if anything, only confirmed to him the correctness of his decision.

“Those of us who had any previous knowledge of men like Rory O’Connor and de Valera were not impressed by their pose of pure-souled patriotism,” Lawless wrote. “I had had a slight experience of Rory O’Connor in Arbour Hill and the Rath Camp and put him down as a crank.”[7]

Getting Out

Crank or not, and whatever else could be said about him, O’Connor was most certainly not one to sit back and do nothing. Deprived of one goal, he soon found another.

Among the first batch of prisoners to arrive at the Rath Camp was David E. Ryan of the Dublin Brigade. “The morning was bitterly cold and a drive of 30 miles was far from pleasant,” as he described the journey in a convoy of ten lorries, with two armoured cars at either end and a pair of military aeroplanes circling overhead. Clearly, the British authorities were taking no chances.

The passengers in Ryan’s transport passed the time by singing patriotic Irish songs, along with a parody of Rule Britannia, much to the amusement of the soldiers guarding them, if only because it infuriated their officer in charge. But ribaldry could only go so far in maintaining morale, and it was a tired and famished group who reached the Curragh, with little in the way of comfort to look forward to:

For the first week, on account of our changed addresses, we received none of the usual parcels from our friends outside, and to say that we were often hungry during that week would be putting it mildly.

Little wonder, then, that Ryan’s thoughts turned to the means of getting out and soon.

For assistance, he turned to O’Connor, who he recognised, despite the fake name the other man went by. Side-lined O’Connor may have been over the prison hierarchy, but his record and standing still inspired respect, at least in Ryan: “He had often planned escapes for others. Now he was to have the pleasure of planning his own.”

The esteem went both ways when Ryan said he would reveal his scheme only on condition of being one of its beneficiaries. “That’s the spirit,” O’Connor replied. “You can do more outside than here. There are too many locked up.”

And so Ryan explained how he had befriended Jerry Gaffney, a fellow IRA member who, while working as a carpenter on the premises – his true loyalty unbeknownst to his employers – had already helped to smuggle out some letters for Ryan. Though O’Connor was at first uncertain as to how far this stranger could be trusted, Ryan vouched for him, and so it was arranged for the three of them to meet the next day in one of the disused huts in the camp.

After reviewing their options, it was assessed that, in the knowledge that the wardens were tightening security, three men at most could make the attempt. Two would obviously be O’Connor and Ryan, as per their deal, but when the latter approached a prospective candidate for the third, the man – who Ryan refrained from naming in his account – declined on account of ill health. With time being of the essence, Ryan and O’Connor decided to proceed anyway with just the pair of them.

Caught Napping

The plan was for Gaffney to procure workmen’s tools and clothing, to be hidden in the same hut until O’Connor and Ryan could walk out, so disguised, amongst the actual workmen at the end of a shift at 5:30 pm. That was until, with two hours to go, O’Connor abruptly cancelled:

The tone of his remark did not invite questions and he went away hurriedly, but knowing Rory well I knew that he had some good reason for calling it off.

The reason, as O’Connor later explained to Ryan, was that if they absconded in the afternoon, the 6:30 roll-call would expose the two missing names. While such discovery was inevitable, O’Connor wanted to put as much distance between them and their jailers beforehand. And so it was agreed to go ahead the next day, at 12:30, which would give their absence almost the whole day of going unnoticed – that is, if all went as it should.

Ryan began having his doubts when he and O’Connor approached the exit. They had donned the dungarees and equipment, and pulled their caps low over faces smeared with dust as a finishing touch, but still Ryan fretted. The tension grew almost unbearable for him:

As we approached the gate I could feel my heart beating quickly, my breathing became jerky and my senses began to weaken.

He kept himself together in time to present his pass to the soldier on duty who, to his silent horror, knew him already as an inmate. Nonetheless, after the longest of pauses, the guard waved him through, whether because the dirt and overalls were a sufficient disguise or, if he recognised Ryan, due to natural human sympathy.

Once out of earshot, O’Connor exulted: “Thank God, they have been caught napping again.”

The fugitives cut through the fields towards Kildare Railway Station, where they bought two tickets, paying a little extra for returns with the money Gaffney had provided. When the authorities asked around for any suspicious duos who might have passed, who would think of the pair who were apparently planning to come back?

After stopping at Lucan, they were walking towards the trams when a lorry-load of Auxiliaries drove down the street towards them. Had their absence been rumbled? O’Connor feared so.

“I’m afraid it’s all up but walk on,” he told Ryan. The Auxiliaries stopped them but only to ask for directions to Newbridge, which O’Connor politely provided.

That night, with Rory I had the pleasure of meeting and being congratulated by Michael Collins, Gearóid O’Sullivan and other members of the GHQ staff, all of whom were delighted to get a first-hand account of the first escape of prisoners from an internment camp in Ireland.[8]

The next day, in Dublin, O’Connor ran into Michael Knightly, a journalist who he had supplied with inside information about the past escapes he organised. It was a pleasant surprise for Knightly:

I had known he was a prisoner at the Curragh and I asked: “When did you get out?” Speaking in his usual slow manner, he said: “Ah, I escaped yesterday.”[9]

David Neligan was another friend who spotted him about town, wearing a beard and clerical garb on the quays. When O’Connor appeared at an IRA gathering on the 14th March 1921, it was to great acclaim, the story of his exploit already in circulation. The celebratory mood was tinged, however, with the knowledge that six of their comrades had been executed that morning in Mounjoy. The solemnity extended to the rest of the city, where the trams stopped for the day, workers took time off and those walking the streets did so in silence.[10]

Suspicious Minds

And so the war dragged on. Exactly how it would end was undetermined: not until complete victory was achieved? Or would some sort of compromise be necessary? “If we clatther them hard enough we might get Dominion Home Rule,” said Dick McKee when asked that question, an indication that he leaned towards the latter resolution.[11]

These opposing viewpoints were in the air, if not quite in the open, during a couple of sessions of the IRA Executive in Parnell Square. On these two occasions, Cathal Brugha, as Minister for Defence and with characteristic pugnaciousness, accused Michael Collins of communicating with Dublin Castle without authorisation. Collins denied any such impropriety, while insisting on his prerogative to accept any information that came his way, whatever its origin.

On a seemingly unrelated note, at another meeting, Collins announced his resignation as Adjutant-General, requesting instead the role of Director of Intelligence. Brugha offered no protest; if anything, he seemed pleased at this development. Perhaps he thought this would clip the wings of the uppity Corkman, for the new post was not, on the face of it, particularly important.

When they were done, O’Connor turned to the man sitting next to him and asked Richard Walsh, the representative of the Connaught IRA, for a quiet word. The two departed from Parnell Square towards Parliament Street, while Walsh mulled over what had just happened. After they reached the Royal Exchange Hotel and found themselves a drink and a quiet corner, O’Connor unburdened himself of his concerns:

Rory was very worried about what Collins’s move meant…When summing up the events of the meeting, Rory O’Connor and myself came to the conclusion that while intelligence, its organisation and efficient establishment, was very necessary, it was also very dangerous as it had a boomerang quality that could hit back in an ugly way.

If intelligence-mining thus needed to be treated with care, was Collins the one to do so? Going by Brugha’s previous remarks about links between him and Dublin Castle, both O’Connor and Walsh were thinking not, as:

The danger would always be there that Collins and his group might use the intelligence system to make contacts to start negotiations with the enemy and make certain commitments that would prove a very serious handicap when proper official negotiations would be taken in hand.

Walsh did not provide a date for this discussion but it was presumably early in the war, before talks between the British Government and the Republican underground began in earnest. Unlike Brugha, who locked horns with Collins whenever he could, O’Connor had previously shown no indication that he held anything but trust towards him; indeed, the two had cooperated on a number of the famed prison-breaks.[12]

If Walsh’s story is accurate, while accounting for the benefit of hindsight, it seems that the factionism that would plague, and finally kill, the revolutionary movement was already incubating beneath the surface.

In a further hint of things to come, another man, Dermot O’Hegarty, walked into the hotel and saw O’Connor and Walsh together. O’Hegarty was a close ally of Collins and it is telling that, when he joined the conversation, an argument soon grew between him and O’Connor. So heated was the exchange that Walsh felt it necessary to call over some of their mutual friends before things got out of hand.[13]

That would come later.

A Surprise Extreme

Still, even after the worse had happened, the past camaraderie could linger on. Piaras Béaslaí and O’Connor were to be mortal enemies, yet, when composing his memoirs, Béaslaí wrote of the other with respect: “He was a man of considerable ability in his particular brand of activity, and…took a leading part in the planning of the most successful achievements of the Volunteers.”

Among these deeds were the jail-breaks of 1919, of which Béaslaí was twice a beneficiary: from Mountjoy in March and then Strangeways, Manchester, in October. The bonds between brothers-in-arms, and perhaps gratitude on Béaslaí’s part, drew together the two men – and future foes – closely enough for Béaslaí to leave a detailed pen-portrait:

He was a man of education and culture who concealed a strong sense of humour under an air of gloomy solemnity. He was dark haired, of medium stature, slightly built, hollow-cheeked, and seemingly not very robust. He spoke in a deep cavernous voice.

However tight they may have been, Béaslaí was still taken aback by the direction O’Connor took when their cause came to a fork in the road. Previously, O’Connor had not seemed “very ‘extreme’ in his views,” but then, Béaslaí was not alone in misjudging him, for “the extreme line of action taken by him after the passing of the Treaty was a surprise to many who knew him well.”[14]

It is possible that not even O’Connor initially knew which way to turn. When Collins returned to Dublin in December 1921 with the rest of the Irish Plenipotentiaries, having put pen to the paper of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, one of the first things he did was to hold a forum of IRA luminaries, including O’Connor, Eoin O’Duffy and Gearóid O’Sullivan, in the Mansion House. Collins could sign whatever he wanted before him, but he was not naïve enough to think that the opinions of the men with guns could be overlooked.

The conference went sufficiently well for Collins to preside over the subsequent luncheon at the Gresham Hotel. Among those present was Father Patrick J. Doyle, being on amicable terms with many of the men at the table, including O’Connor, who had joked in the past about how the priest would end up on the scaffold for his seditious acquaintances. As the party ate, Father Doyle was able to observe the demeanour of his friend:

Although Rory had voted at the Volunteer meeting against acceptance of the Treaty, he was quite reconciled to abide by the majority decision of the Volunteers in favour of it.

Far from brooding on what had happened, O’Connor appeared to be looking forward to the future:

During the lunch, he took part in an animated discussion about the formation that the new Irish Army should adopt and urged very enthusiastically the adoption of the Swiss system of formation.

And yet, as Doyle observed, “a few months later Rory was out in armed opposition to the Provisional Government.” The whole thing remained a mystery to the priest, even after the passage of time:

I have never yet met any of the Volunteer officers who took up arms in that cause who could give a coherent account of the tragic split that ensued after the acceptance of the majority decision.[15]

From the start, however, there were warning signs. Liam Archer worked under O’Connor in the IRA Engineering Department, and they were in the latter’s office on Marlborough Street, Dublin, when word of the Treaty reached them. Archer was as shocked as anyone at the idea of an Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch and asked O’Connor, as they walked to Collins’ own base in the Gresham, what they were to do:

He answered without hesitation – Oh, we must work it for all its worth, then after a slight pause he added But if I could get enough to support me I would oppose it wholeheartedly.[16]

In that, O’Connor would be true to his word.

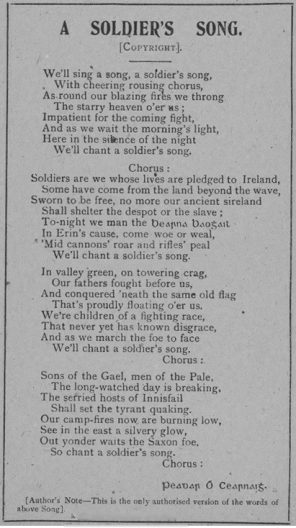

The Soldier’s Song

Even before the Treaty was ratified by the Dáil in January 1922, and while the delegates to that national body debated the merits of the Anglo-Irish agreement, O’Connor met with four other senior IRA officers – Ernie O’Malley, Liam Lynch, Séumas Robinson and Liam Mellows – for a parliament of their own on Heytesbury Street. The house at number 71 had been a reliable bolt-hole during the fight with the British and now it would serve as a venue for a conspiracy – this time against their own side.

“Rory’s eyes were sombre,” O’Malley noticed. “I noticed the grey streaks in his black hair.”

While all present were of like mind that the Treaty was unacceptable, binding as it did Ireland inside the British Empire, they were less certain on where the rest of the IRA stood. O’Connor wanted to waste no further time. “They mean to enforce to Treaty, but we must organise,” he said.

He was in favour of breaking away from GHQ as soon as the Dáil debates were over, seemingly not interested in whatever the result was. O’Malley approved of this bold course of action, as did Robinson, with Lynch keeping his own counsel – the odd man out, even then – and Mellows in less of a hurry, as he assured the others that the IRA would never tolerate the Treaty anyway. That the Dáil or the public might differ in opinion did not seem to occur to anyone, at least not to the extent it was worth considering.

Mellows’ wait-and-see attitude carried the room, perhaps because no one wanted to make a definite decision, and it was agreed between them to keep in touch while seeking whatever allies that they could. “Rory’s quiet humour broke the gravity,” wrote O’Malley in his memoirs, “soon we were chatting and laughing.”[17]

It was no great surprise, at least to O’Malley, when the Dáil voted to ratify the Treaty. Éamon de Valera resigned as its president in protest, though he appealed at a meeting of military men to put politics aside for the sake of unity and peace: a ship that had already sailed, to O’Malley’s mind, and to O’Connor’s as well.

The two met again when O’Malley dropped by the other’s house in Monkstown. O’Connor greeted him at the door, happy to see him, having sent word, which O’Malley had missed, for another, more exclusive, conclave that was to take place that evening in Dublin. While waiting, they killed time by playing records on the gramophone in the front room. The last tune was The Soldier’s Song, the anthem to the revolution, except O’Connor misplaced the needle of the gramophone, which drew out the notes and distorted the lyrics; appropriately so, thought O’Malley, a sign of the mess they were all in.[18]

Out in the Open

Out in the Open

The pair took the tram to Grafton Street and then walked to Nelson’s Pillar, continuing on to the back of Marlborough Street where O’Connor conducted his work. More soon came, coming up the wooden steps to the main office: Liam Lynch, Michael McCormick, Oscar Traynor, Tom Maguire, Seán Russell and others.

The room was not well lit. We sat on chairs forming three sides of a square, which Rory’s desk completed. A prismatic compass, a map measurer and a celluloid protractor stood against the ledge of the desk. To one side of them were coloured mapping inks and small slender mapping pens. Maps hung on the wall – a large scale map of Dublin; a map of Ireland with the divisional areas inserted in red pencil.

O’Connor’s skin, O’Malley saw, looked darker than usual. The light from the windows touched his cheeks and cast the rest of his face in shadow.

Once he was made chairman, O’Connor got to the point: GHQ could not to be trusted. The IRA still stood but not for long, as O’Connor was sure it would be disbanded and replaced with tame pro-Treaty cuckoos. Already the Provisional Government was recruiting men for such a move, while those who might oppose it were confused and directionless.

With time thus of the essence, it was agreed by the men in the room, as O’Connor jotted down the minutes, for an IRA Convention to be held, the first in a long while. If the Provisional Government was to refuse one, then an independent command was to be formed at once, both as an alternative and a challenge.

Such was the mood that when Richard Mulcahy, shortly after O’Connor’s military meeting, called one of his own in the Banba Hall, Parnell Square, O’Malley attended with two revolvers hidden beneath his coat. Pro-Treaty officers sat in one half of the semi-circle of chairs, Anti-Treatyites making up the other, as if to formally announce the break.

Choosing to overlook this unfortunate placement, Mulcahy, now the Minister of Defence, announced that their forces would continue to be the Republican Army. But O’Connor was not buying it. “A name will not make it so,” he said caustically as soon as Mulcahy had finished his piece.

The meeting escalated to Collins being called a traitor, provoking the Corkman to his feet in a rage. Mulcahy defused the tension with a few quiet words – an impressive feat, considering the passions simmering in the room. In a gesture of good faith, he proposed that the Anti-Treatyites appoint two of their number to attend GHQ meetings and ensure that nothing untoward was done.

O’Connor asked for some privacy in another room to discuss this and, when there, asked the others what they thought. Most wanted to break away then and there with no further time wasted but Lynch insisted they give Mulcahy’s idea a try. As Lynch was in charge of the Cork and Kerry brigades in the First Southern Division, the largest and best-armed of the IRA blocs outside Dublin, the rest had no choice but to comply.

At least Mulcahy was open to the idea of an overdue IRA Convention. The Army had begun as an independent body, with its own procedures and policies and, for some like O’Connor, it was time to revive it as such.[19]

Law of the Jungle

Lynch had inadvertently exposed two profound and disturbing truths. Firstly, while the Anti-Treatyites could or would no longer work with their pro-Treaty counterparts, they were scarcely more united among themselves.

The second was that, for all the lofty talk, strength was what really counted. This was quickly grasped by O’Malley, who put the lesson to the test when he returned from Dublin to where he held sway as O/C of the Second Southern Division, encompassing IRA units from Limerick, Tipperary and Kilkenny. Of the five brigades under his command, four were willing to follow his lead in resisting the Treaty, which meant, in more immediate terms, his former superiors in GHQ.

The first opportunity to make their discontent known was in Limerick in March 1922. British troops had withdrawn, as per the Treaty terms, leaving their barracks open for the taking, and O’Malley was determined that the Pro-Treatyites would not be the ones benefitting. A stand-off ensued as local IRA men from the opposing – and increasingly belligerent – factions hastened to seize and secure whatever positions they could in the city. Reinforcements came from Dublin and Clare for the Pro-Treatyites, while O’Malley was joined by Tipperary and Cork cohorts.[20]

Not even two months had passed since the Treaty was signed and the country was already on the brink of fratricide – still, better sooner than later, in O’Malley’s view.

This was the argument he put to O’Connor when O’Malley briefly returned to Dublin, but O’Connor, having been so adamant at the start, now pulled back in the eleventh hour. There was still a chance at a bloodless resolution, he told O’Malley, as he turned down the request for aid to be sent. O’Malley and his allies were on their own in Limerick, though O’Connor, rather lamely, expressed the hope that all would work out for the best.[21]

This was the argument he put to O’Connor when O’Malley briefly returned to Dublin, but O’Connor, having been so adamant at the start, now pulled back in the eleventh hour. There was still a chance at a bloodless resolution, he told O’Malley, as he turned down the request for aid to be sent. O’Malley and his allies were on their own in Limerick, though O’Connor, rather lamely, expressed the hope that all would work out for the best.[21]

Things did – briefly.

Negotiations in Limerick led to a face-saving agreement for both sides to back down with honour intact, proof that the split was reversible and conflict not inevitable. That is, until later that month, on the 22nd March, when Mulcahy announced that any IRA convention, such as the one set to take place in four days’ time on the 26th – which he had been previously agreeable towards – was “contrary to the orders of the General Headquarters staff, and will be sectional in character.” Any officer in attendance could consider themselves stripped of rank.[22]

For those who had distrusted Mulcahy and the rest of the Provisional Government from the start, this was all the vindication they needed. Just after Mulcahy’s proscription, on that same evening, Irish reporters, as well as ones in Dublin on behalf of British and American newspapers, received an invitation to a press conference in Suffolk Street.

As the Republican Party had its offices there, the pressmen who accepted might have expected the presence of someone like Éamon de Valera – no longer the President of the Republic, but still the most recognised politician in the anti-Treaty ranks. Instead, in walked a relative stranger who took his place at the large table in the centre of the room before the assembled newshounds.

Man: Gentlemen, I understand you want to know something about army matters.

Journalist: Who are you?

Man: I am Roderic O’Connor, Director of Engineering, General Headquarters.

Another journalist: Do you represent GHQ?

O’Connor: I do not represent GHQ. I represent 80 per cent of the IRA.

Not Peace But a Sword

In regards to the remaining 20 per cent, O’Connor said, when asked further, he hoped in time to win over 19 per cent. “Dáil Éireann,” he continued:

…has done an act which has no moral right to do. The Volunteers are not going into the British Empire, and stand for liberty.

This defiance on O’Connor’s part, and that of the 80 percent of the Army if he spoke true, had been some time in the making, as O’Connor went on to explain.

While the Treaty, the immoral act O’Connor had spoken of, was being debated at the start of the year, IRA officers from the South and the West of the country had come to him and Liam Mellows to say how badly they felt let down. To right this wrong, an IRA convention was set to be held four days hence, on the 26th March, and though the Provisional Government had banned it, the event would go ahead anyway.

Which was only proper, considering how:

The Army feels that the Dáil has let down the Republic and has created a dilemma for the Army and the country. The Army feels it must right itself. It has sworn an oath of allegiance to the Republic, whilst giving its allegiance also to the Dáil.

Such a choice was no choice at all, in O’Connor’s strident view. He was, however, hazier on a number of questions put to him.

Journalist: Take it that the Irish people vote 80 per cent, or more, in favour of the policy adopted by the Dáil, will the attitude of the 80 per cent of the Army whom you claim to represent be the same towards them as you say it is now towards the Dáil?

O’Connor: I cannot answer for the Army on that. That will be a question for the new Executive which will be set up next week.

Journalist: Is the army going to obey Mr de Valera or the people, through those they put in control?

O’Connor: President de Valera asked that the army obey the existing GHQ, but the army for which I speak cannot, because the Minister of Defence has broken his agreement.

As for how Mulcahy, the Minister in question, had done so, O’Connor explained that it was by asking IRA members to join an alternative army, one set up for the purpose of keeping Ireland inside the British Empire. Mulcahy might deny it, but O’Connor held that it was true all the same. As for the allegiance of the IRA, that answer was obvious:

The Republic still exists. There are times when revolution is justified. The army in many countries has overturned Governments from time to time. There is no Government in Ireland now to give the IRA a lead, hence we want to straighten out the impossible position which exists.

The Dáil was certainly not such a government, at least not how O’Connor saw it. Certainly, if the Dáil was in fact the Government, then the IRA was presently in revolt against it. O’Connor’s tone was matter-of-fact, as it was when questioned further on the obvious consequences of soldiers making their own decisions.

Journalist: Do we take it we are going to have a military dictatorship, then?

O’Connor: You can take it that way if you like.

Journalist: Then the convention won’t make for peace?

O’Connor: It will make for the liberty of the country, I believe. The Treaty section is going off the straight road and into the bogs to get freedom. We hold that is wrong.[23]

To be continued in: Out of the Republic: Rory O’Connor and the Start of the Civil War, 1922 (Part IV)

References

[1] Lawless, Joseph (BMH / WS 1043), pp. 267-8

[2] Andrews, C.S. Dublin Made Me (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001), p. 238 ; Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland, Volume 1 (Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008), p. 131

[3] Neligan, David. The Spy in the Castle (London: Prendeville Publishing Limited, 1999), pp. 79, 127

[4] Lawless, pp. 389-91

[5] Ibid, pp. 400-1

[6] Ibid, pp. 402-3, 405

[7] Ibid, p. 432

[8] Ryan, Daniel E. (BMH / WS 1673, pp. 5-10

[9] Knighty, Michael (BMH / WS 834), p. 16

[10] Neligan, p. 127 ; O’Malley, Ernie (Aiken, Síobhra; Mac Bhloscaidh, Fearghal; Ó Duibhir, Liam; Ó Tuama Diarmuid) The Men Will Talk To Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018), p. 131

[11] University College Dublin Archives, Michael Hayes Papers, P53/344

[12] Walsh, Richard (BMH / WS 400), pp. 71-3

[13] Ibid, p. 76

[14] Béaslaí, pp. 130-1

[15] Doyle, Patrick J (BMH / WS 807), pp. 21, 32-3

[16] Michael Hayes Papers, P53/344

[17] O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), pp. 61-3

[18] Ibid, pp. 65-7

[19] Ibid, pp. 67-72

[20] Ibid, pp. 72-4, 76-7

[21] Ibid, pp. 80-1

[22] Irish Times, 23/03/1922

[23] Evening Herald, 22/03/1922

Bibliography

Books

Andrews, C.S. Dublin Made Me (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001)

Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland, Volume I (Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008)

Neligan, David. The Spy in the Castle (London: Prendeville Publishing Limited, 1999)

O’Malley, Ernie (Aiken, Síobhra; Mac Bhloscaidh, Fearghal; Ó Duibhir, Liam; Ó Tuama Diarmuid) The Men Will Talk To Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018)

O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Doyle, Patrick J., WS 807, p. 33

Knightly, Michael, WS 834

Lawless, Joseph, WS 1043

Ryan, Daniel E., WS 1673

Walsh, Richard, WS 400

Newspapers

Evening Herald

Irish Times