A continuation of: A Prominent Republican Leader: The Trials and Tribulations of Seán McGarry, 1913-1919 (Part I)

The Men Behind the Men

Imprisonment barely slowed McGarry down. After his release in December 1916 as part of the general amnesty, he was hard at work again with the resurgent republican cause, the immediate goal being to ensure the IRB and the Irish Volunteers remained joined at the hip, and the former in charge.

Which was simple enough: in October 1917, candidates doubling as IRB initiates gained all the seats on the Volunteer Executive at the latter’s Convention, with McGarry as General Secretary and an up-and-coming Michael Collins as Director of Organisation (Collins was first nominated as Secretary but withdrew in favour of the other man).[1]

While the movement was in robust health and McGarry’s role in it a prominent one, he did not always get his own way. In mid-1917, the topic of conversation at Fleming’s Hotel, Gardiner Place, was the impending bye-election in Clare, where Éamon de Valera was planning to contest as a Sinn Féin candidate. Although not strictly an IRB meeting, most of those present in Fleming’s were members.

McGarry protested against the possibility of Eoin MacNeill’s involvement in the election, considering him persona non grata for his attempts to countermand the Rising (he was equally pitiless with another miscreant who had tried to interfere, writing to the disgraced Bulmer Hobson in March 1918 on behalf of the Volunteer Executive for him to return any monies or properties belonging to the Volunteers and submit himself for court-martial).[2]

McGarry was overruled by de Valera, however, who threatened to boycott his own campaign if MacNeill was not permitted.[3]

The two men could not have had more divergent opinions. De Valera had joined the IRB shortly before the Easter Rising upon learning to his shock that his Brotherhood-connected subordinates knew more about the plans for the rebellion than he did. He left soon afterwards and would nurse a distaste for the fraternity.[4]

“Curse secret societies,” de Valera wrote later, adding that he had been tempted several times to take “drastic action” against the IRB but held off for fear of the turmoil that might cause.[5]

A Question of Authority

Sometime before the polling day in Clare, another gathering was held in Limerick by IRB luminaries such as Austin Stack, Seán Ó Muirthile, Thomas Ashe, Ernest Blythe as well as McGarry. Stack asked the others why they were not at their posts in Clare in accordance with their candidate’s orders.

“Who gave de Valera authority to order us about?” McGarry groused. The remark triggered an impromptu discussion on whether or not it was appropriate for the Brotherhood to be involved in political matters. It was the last sort of question that a secret society like the IRB would want aired.

In the end, the others obligingly departed for Clare to assist de Valera except McGarry who made his way back to Dublin in a huff. If McGarry had thought that the new politicians were going to be at the IRB’s beck and call, then he was sorely behind the times.[6]

Given the tension between McGarry and de Valera, it was only fitting that the two men should be thrown together when they were arrested and deported to England in May 1918 along with others as part of the supposed ‘German Plot’. Michael Collins had been on his way to warn McGarry of the impending arrests but arrived too late (a practical man, Collins then stayed the night at McGarry’s house, reasoning that the authorities would be unlikely to return to a place they had already raided).[7]

McGarry had by then risen to become President of the IRB Supreme Council. The historian Leon Ó Broin could not resist noting how two presidents of the Irish Republic had been imprisoned together in Lincoln Prison, de Valera of Dáil Éireann and McGarry due to the IRB constitution proclaiming its head to be de facto that of the Republic (although this is perhaps not an idea that stands up to serious scrutiny).[8]

A Man’s Work, Done by Men

Confinement did not hold either man for long. In the weeks following the well-publicised escape, in February 1919, of McGarry, de Valera and a third man, Seán Milroy, from Lincoln Prison, Harry Boland felt the need to rebut some of the stories that had been circulating.

Speaking to the Evening Herald in his role as Honorary Secretary of the Sinn Féin Executive, Boland dismissed the existence of the ‘Ultra-Irish Society’, a thinly-veiled depiction of Sinn Féin, which was supposedly behind the jailbreak. What particularly jarred him was the rumour that girls had been brought over from Ireland to flirt with the English gaolers as a honeypot distraction.

“We have too much respect for our Irish girls to subject them to such humiliation,” Boland harrumphed. “President de Valera’s rescue was a man’s work and was done by men.”[9]

The real story behind the escape was surreal enough without the need for femme fatale colleens. Michael Lynch, a Volunteer of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in Dublin and a friend of McGarry’s, was visited by Tomasina McGarry, some eight or nine months after her husband was deported.

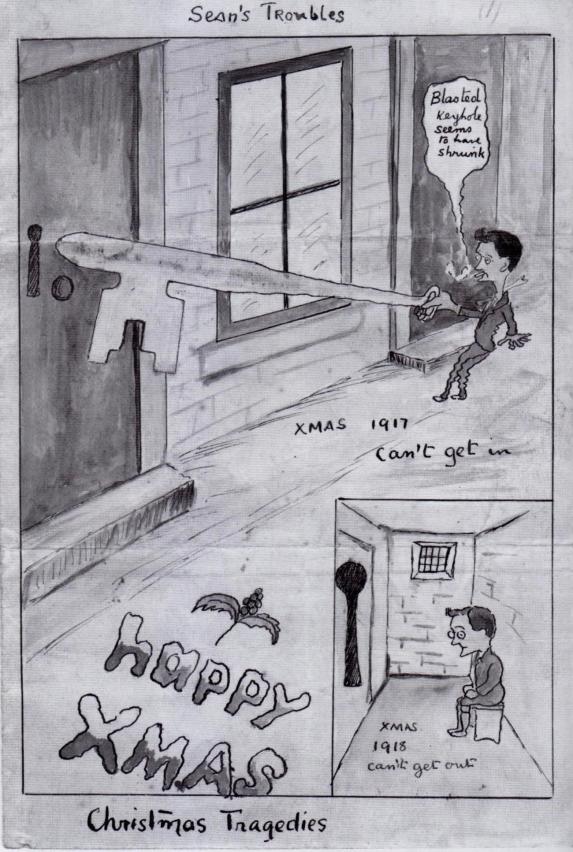

She had received from him a most puzzling postcard with two pencil sketches of a man whose thin, bespectacled face bore more than a passing resemblance to her husband’s. In one of the cartoons, the gentleman was trying vainly to open a door with a comically oversized key. Beneath, it read: 1917 – can’t get in.The second sketch showed the now despondent fellow sitting in cell before an also-comically oversized keyhole, with the words: 1918 – can’t get out.

“Did you show this to Michel Collins?” asked Lynch, according to his recollections.

“No. Why should I?” she replied.

“I think you had better.”

Collins lost his temper when shown the card, demanding to know why the hell Tomasina had kept it to herself for so long. It turned out that the cartoons were a coded message from the prisoners in Lincoln Prison, covertly asking for a key to be sent over.[10]

Escape

Tomasina McGarry could be forgiven for not knowing a code she had not been privy to, especially how mystified everyone else was.

The card had been initially sent to a sympathetic priest in Leeds, minus any actual instructions on what to do with it. The padre took the items to Liam McMahon, a senior member of the IRB in Manchester, but the latter was equally stumped. McMahon at least had the inkling that the card was supposed to convey something, so it was forwarded to Dublin, where it ended up in the possession of Tomasina, although that was not the end of the confusion, as McMahon put it:

I believe they had the same difficulty in Dublin in trying to find anything in them. Eventually, I think Collins tumbled to the fact that there was something in them.[11]

That something was a request from the prisoners for a key. Several were made, based on the drawing in the postcard, and smuggled into Lincoln Prison via cakes (one baked by McMahon’s wife). None of these keys, however, fitted the locks.

Finally, one of the prisoners, Peter de Loughry, was able to duplicate one by unscrewing the lock off the door of the common-room where the inmates were allowed to be unsupervised every afternoon. A skilled craftsman, de Loughry was able to work steadily on his project every day before the lock would be reinserted into the door in time for the guards’ return.

McGarry would wonder at how they ever got away with it, considering how every time the lock was removed from the door its hole was gradually widened until it was ready to fall out. But got away with it they did.

Meanwhile, the rescue team, including Collins and Boland, had come over to England where they were using McMahon’s house in Manchester to plan the operation. McMahon was assigned to secure a taxi and wait with it in Sheffield on the appointed day of the 3rd February. Collins and Boland journeyed to Lincoln Prison with a spare copy of the key de Loughry had made in case anything went amiss – which, in obedience to Murphy’s Law, it did.

The two rescuers approached the door in the prison wall, near the courtyard on the other side where de Valera, McGarry and Milroy were due to come. Collins and Boland waited by the door for a tense while until they heard the muffled sounds of footsteps from the inside. After ascertaining that they had the right men, Collins put his key in the lock and gave it a sharp turn.

The key, much to everyone’s horror, promptly snapped.

Before anyone could panic, de Valera saved the situation by producing his own spare copy which he inserted into the lock, pushing out the broken one. The door swung open and the three absconders padded out in their canvas slippers which they had worn to deaden the noise. Looking back, McGarry was to rue not locking the door behind them for added effect, as that would have made their escape all the more mystifying.[12]

In Sheffield, McMahon was waiting impatiently in his taxi, with frequent glances at his watch, when de Valera, McGarry and Milroy made their appearance. As McMahon drove the three runaways to Manchester, McGarry talked about all the possible ways they could get to Dublin.

In a sign that their time spent locked up together may not have been an easy one, de Valera turned to McGarry and said, in McMahon’s recollections: “Don’t you think the men outside have done very well so far? Why not leave it to them to do the rest?”

That was the end of the chatter, much to McMahon’s relief. His part completed, McMahon last saw McGarry on his way to the train station for Liverpool disguised as a bookie.[13]

The Return Home

McGarry’s return to Dublin was a discreet one without fanfare or fuss. He was able to hide at Lynch’s house on Richmond Road after Collins had dropped by the day before to let the family know the fugitive was coming. Collins did not seem to ask for permission, but Lynch, as a member of the Irish Volunteers, could hardly refuse sanctuary to a fellow freedom-fighter.

What could have been a strained situation in the house, particularly with McGarry unable to step outside for fear of recognition, was elevated by his general good humour. He was fond of jokes and stories, according to Lynch, and was fortunate enough to befriend Lynch’s new wife, who was not above adding to the humour by pranking her guest.

Noting a habit of McGarry’s to overuse the firepoker – at least ten times within half an hour in one sitting – Mrs Lynch sneakily applied a liberal amount of polish to the handle. She then waited as the unsuspecting target prodded at the fireplace as per habit while absentmindedly rubbing his face. Confused as to the gales of laughter from the rest of the household, it was not until he stood up and looked in the mirror that he saw the blackness smeared all over his features.

The victim was not amused, as told by Lynch, somewhat belying what he said about McGarry’s constant geniality: “He chased my wife round and round the table. She saved herself by running down the garden, and all Seán could do was stand at the kitchen door and curse.”

It was not all ‘fun’ and games. Tomasina was unable to see her husband lest she bring unwanted attention. The nearest thing to contact McGarry could have with his three children – Emmet, Sadie and Desmond – was for them to be taken by the family maid for a walk every afternoon, if the weather permitted, to Richmond Road, from where McGarry could peer out for a glimpse of them. However unsatisfying, it was the most he could have.

After first consulting with Collins, it was agreed that enough time had passed for Tomasina to come over. One day, she brought their son, Emmet, who, at the age of three, had only vague memories of his long-absent father. He had been told beforehand they were visiting the doctor and was none the wiser during the course of the surreptitious reunion, until:

[Emmet] crept up on his daddy’s knee, and he told us all, in his little innocent way, that he was a very nice doctor. Then, suddenly, recognition, came into the little kid’s eyes. He threw his arms around his father’s neck and cried out, “You are my daddy!”. It was the most moving scene I ever remember, not only for Seán, but the whole lot of us felt the tears in our eyes.

A chip off the old block at keeping secrets, little Emmet kept his visitations to his father to himself. His twin sister, Sadie, was also brought to the Lynch house; that way, the McGarrys were able to maintain some semblance of overdue family life.[14]

The War Continues

It was almost a month after the jailbreak when Collins had the idea of publicly unveiling McGarry, the chose venue being a public concert at the Mansion House. Posters advertised the presence of a “prominent Republican leader” who would be speaking at the concert but no names or further details were given until the evening of the concert on the 4th March when McGarry marched on stage in the uniform of the Irish Volunteers. After a brief speech, the returned hero was bundled out of the building and driven away before the nearby policemen could interfere.[15]

By now a public figure, McGarry entered the arena of politics on behalf of the now ascendant Sinn Féin party. He was already a councillor in Dublin Corporation, having been introduced as such by the Lord Mayor at the Mansion House concert. The Corporation had met for a special session a month earlier, in February 1919, to replace a recently departed member. As per the rules, the replacement could be selected by the party of the deceased – in this case the beleaguered Irish Parliamentary Party – but the nominee withdrew in favour of Sinn Féin’s McGarry.

It was a sign of the times that, in the words of historian Pádraig Yeates:

The fact that he was on the run…and that this might hamper him in the discharging his duties as a public representative, does not appear to have been considered an impediment.[16]

Come the start of 1920, McGarry ran as a candidate for alderman in Dublin Corporation, and later as a TD for Dublin Mid in the 1922 general elections, winning both times on a Sinn Féin ticket.[17] It is unclear if he entered politics on his own volition or due to instructions but given his essentially passive nature, the latter seems most likely.

His newfound public role carried its own set of dangers as McGarry, still a man on the run, was obliged to attend council meetings. In December 1922, armed Auxiliaries intruded upon one such session of Dublin Corporation. All those present were questioned, resulting in six of them being taken away in custody.

The officer in charge had called out the list of names present in the roll book. When he came to McGarry, a voice responded: “Not here.” At the same time, Margaret McGarry, another Sinn Féin member of the Council and no relation, remarked: “My name is McGarry, perhaps it is me?”

Whether meant in jest or confusion, she was quickly told to shush by the Lord Mayor. When the Auxiliaries left, it was without McGarry among their catch of prisoners, either because he had left the room in time or had been able to remain undetected inside.[18]

Out of Sight

For the most part, however, McGarry drops out of the historian’s view during the months of the War of Independence. His reticence in revealing too much, either to the Bureau of Military History (preferring to dwell more on his mentor, Tom Clarke, than on himself) or the Military Pensions Board (where he was already assured of a pension, having been in the National Army as a captain during the Civil War), means that it is hard to reconstruct his activities in any great depth.

It is not even clear if he stayed on in Lynch’s house after being ‘outed’ in the Mansion House or if he moved elsewhere. His entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography describes him as being “captain in the IRA Dublin Brigade throughout the war of independence” but no other source supports this.[19]

While imprisoned in Lincoln, he had been replaced as President of the IRB Supreme Council by Harry Boland, and later Collins.[20] A follower rather than a leader, McGarry made no effort to regain his presidency, seemingly content to leave it to Collins. McGarry would serve his successor as he had previously done for Tom Clarke and Seán MacDermott.

As part of this, McGarry was sent to Britain sometime in April/May 1921 to touch base with the few isolated Volunteers and the remnants of the IRB there. According to one of those he talked to, the fight for freedom was nearly at the end of its tether in Ireland. If the cause was to be abandoned until the next generation were ready to resume, then the Brotherhood would best be reorganised among the young. [21] His efforts did not result in any great success. However, the British-based IRB was too much in disarray, and “Sean gave up in despair.”[22]

Speaking to a journalist in 1955, de Valera recalled how McGarry, “whom he did not think much of,” called to see him one day in December 1920 “and spoke to him on authority about should be done,” presumably about the ongoing war with Britain. McGarry had apparently been so circumspect that de Valera did not even realise that his guest had come on behalf of the IRB. De Valera assumed that the other man had come in a private capacity and was “merely…talking big to impress.”

It was only after his visitor was gone that de Valera remembered that he was in the IRB, although the former’s information was out of date as he assumed that McGarry was still its president. Historian Tim Pat Coogan commented that McGarry “was more likely the Brotherhood’s Secretary and certainly a member of the Supreme Council.”[23]

Actually, it is not certain at all if McGarry was still on the Supreme Council or, if not, when he had stopped being so. He was absent at a critical meeting of the IRB Supreme Council – called to discuss the Treaty crisis – on the 19th April 1922, despite the presence there of Michael Collins, Seán Ó Muirthile and Diarmuid O’Hegarty, who had each played a role in ‘unveiling’ him at the Mansion House three years ago.[24]

Michael Collins

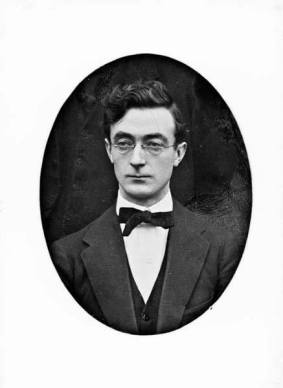

McGarry remained close to Collins, holding a place in the other man’s affections as a living totem of the recent past. During the course of his interviews with the American journalist Hayden Talbot, between December 1921 and the following August, Collins complimented McGarry as “the one man who was closer in the confidence of the leaders of the rising than any other man today” – high praise, indeed, considering the hallowed status of said leaders.

Collins was keen for Talbot to meet McGarry for him to give the inside scoop on the Easter Rising and the Howth Gunrunning, both of which he had been intimately involved. The first scheduled meeting fell through due to the Civil War making the streets of Dublin too dangerous for McGarry to travel through. He was able to make it at the next one on the 2nd August 1922, and dutifully relayed to Talbot what he knew while Collins looked on.

McGarry was the very image of the deferential subordinate, at one point glancing at his Commander-in-Chief for advice on how to answer Talbot’s latest question. Collins did not always reciprocate the courtesy. Thinking that the interview had gone on for too long and it was his turn to speak, he brusquely interrupted McGarry, who took the cue and dutifully left for the night.[25]

Tomasina McGarry

In contrast to the relative obscurity of McGarry’s wartime activities, his wife’s are much more accessible. Lacking the military rank of her husband with its guarantee of a pension, Tomasina McGarry was obliged to be more forthcoming in her application to the Military Pensions Board.

In her typed statement in 1945, she told of how during Easter Week 1916 she had delivered letters that her sister had carried from the GPO. Service in the War of Independence in Dublin included her acting as a go-between for Collins and his moles within the DMP. One conveniently lived next door to her and was able to pass on warnings of impending police raids nine or ten times.

Otherwise, her duties were small and infrequent but essential to the smooth maintenance of an underground army, such as finding accommodation for Volunteers when needed, allowing weapons to be stored at her house or, on one occasion, passing on two revolvers purchased by her sister from an enterprising Black-and-Tan.[26]

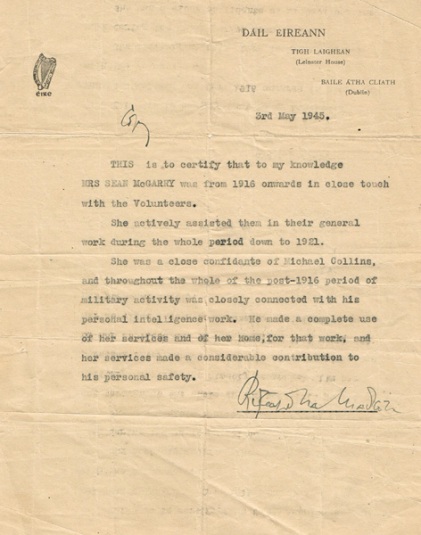

Tomisina had an impressive list of references. Richard Mulcahy confirmed to the Board that:

She was a close confidante of Michael Collins, and throughout the whole of the post-1916 period of military activity was closely connected with his personal intelligence work. He made a complete use of her services and of her home, for that work, and her services made a considerable contribution to his personal safety.[27]

Others agreed. Gearoíd O’Sullivan described her as “a great one in efficiency and thoroughness,” and how she had stored for Collins papers relating to IRB funding. Leo Henderson told of how she had “rendered great service to the men of the movement; a confidante, conveying messages,” and confirmed a story of him retrieving a gun from its hiding place in her kettle at home (unfortunately, Tomisina was found by the Board to be illegible for a pension).[28]

The Dáil Debates

As a TD, McGarry was entitled to contribute to the debates in the Dáil over whether to ratify the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Speaking on the 3rd January 1922, he began by promising to make a record for brevity. According to some journalists who were present, “he didn’t, but he went so near that we forgave him.”[29]

Considering the not-inconsiderate length of his speech as it appears on the printed page, including interjections by others and his comebacks, all of which apparently took just ten minutes, it can summarised that McGarry spoke very quickly indeed.

With this soon-to-be-broken promise made, he wasted no time in making his choice clear. He supported the ratification of the Treaty with no apology. Shifting from a defensive stance to an offensive one, he proclaimed that he did not wait until he was a member of the present Dáil before becoming a Republican (unlike, presumably, others in the room, though he left any names unstated).

He had worked in the Republican movement for twenty years. He was a Republican that day and he would be a Republican the next, and, as such, he would be voting for the Treaty as it stood:

For that I do not need the opinion of a constitutional lawyer or a constitutional layman or a Webster’s Dictionary or a Bible to tell me what it means. I put on it the interpretation of the ordinary plain man who means what he says. I am not looking for any other interpretation from Webster’s Dictionary or anywhere else. I know what the Treaty means, and the man in the street knows what it means.[30]

This display of impatient insistence could be attributed to the effects of having to listen to – as historian Jason K. Knirck puts it – the previous, seemingly “endless speeches, many of which seemed overly abstract and theoretical.”[31]

McGarry was not the only one to display abstraction fatigue. Speaking on the following day, James Murphy, TD for Louth-Meath, opened with an admission that “not being a constitutional lawyer I do not possess the art of saying nothing in a great many words. Consequently I can relieve the House by assuring it that I will be very brief” (unlike McGarry, Murphy was true to his promise). Shortly afterwards, James Burke, TD for Tipperary Mid, assured his audience, that despite being a lawyer, he was not going to “indulge in a long and laboured dissertation on constitutional law.”[32]

Fencing in the Dáil

Lambasting the naivety of those who had had inflated expectations of what the London talks could achieve, he asked: “What did we think we were sending to Downing Street for? Did any of us think we were going to get an Irish Republic in Downing Street?”

To this, the ardently anti-Treaty Mary MacSwiney piped up: “Of course you could.”

“A Downing Street Republic?” McGarry said incredulously, prompting laughter from the room.

MacSwiney held her ground. “No, a Downing Street withdrawal from Ireland.”

“Downing Street are withdrawing from Ireland.”

“No, they are not.”

Stalemated, McGarry switched on to another tactic: mockery, directed towards the apparent inconsistency in the form of Document No. 2. The brainchild of Éamon de Valera, Document No. 2 was intended as a bridge between the two factions as a slightly rewritten version of the Irish stance during the London talks, with the inclusion of the more acceptable elements of the Treaty to round it off as a compromise.

While it was to be praised by many historians as a “powerful, sophisticated piece of political thought”, the apparent climb-down from a steadfast Republic-and-nothing-but-the-Republic line to a far less glamorous-sounding alternative made the Document an easy target for McGarry to home in on:[33]

Several Deputies protested very strongly and very loudly that they were standing on the bedrock of the Irish Republic. A week before they were standing on the slippery slopes—to borrow a phrase of the Minister of Finance—the slippery slopes of Document No. 2. Document No. 2 was pulled from under their feet and landed them with what must have been an awful jerk on the bedrock of the Irish Republic. They will be standing on that until the proper time—I mean the time when Document No. 2, or perhaps Document No. 3 will be given to us.[34]

“You can have it immediately if you like, whatever your side agrees,” de Valera retorted. It was a fairly nonsensical comeback which made it sound as if he actually had a Document No. 3 at hand, but probably said in the heat of the moment.

McGarry again did not linger, moving onto a different subject and another chink in the Anti-Treatyites’ armour; in this case, their lack of popular support:

There has been theorising in some of the speeches made here by Deputies about Government by the consent of the governed—self-determination. You can have government in Ireland to-day by consent of the governed with this Treaty. You can have self-extermination without it; but you cannot have war without the consent of the Irish people. And the only reason you carried on war for the last two years was because you had the consent of the people.[35]

McGarry accused the opposition of gambling with their belief that for all the talk of resuming the War, they would not have to actually do so. He admitted that he had indulged in a bit of gambling before but, he added wryly, never on a certainty that did not end up leaving him poorer.

To laughter and cries of “hear, hear”, he followed up his punchline with a stinger: “They are quite right, they are not going back to war; they are going back to destruction.”

McGarry finished with a pair of dark quips, the first a quote from the 19th century English writer Charles Lamb about the Chinese man who burnt down his home to roast a pig. The second was a Biblical allusion: “It was Samson who pulled down the pillars of the Temple. That was his funeral. I do not want to attend the funeral of the Irish nation.”[36]

It was on these eerily prescient citations – for him as well as for the country as a whole – that McGarry finished his contribution. It had been a rather ungainly series of points strung together, rather than a smooth narrative with a fixed beginning, middle and end. McGarry may have revealed his weaknesses as an orator that day, but his arguments had at least been impassioned and direct, making it one of the few times this otherwise reticent man expressed himself in public so forcefully.

The Civil War Breaks

McGarry could be pointed in his rhetoric but he was without rancour himself. On the 11th January, he felt the need to write to the Irish Independent in response to a letter published four days earlier from a Margaret McGarry. Her surname had led others to assume they were related. It was a misunderstanding Seán was keen to correct due to her choice of words: “I should be sorry that any relative of mine should refer to Mr. de Valera in the terms contained in the last paragraph of that letter.”[37]

There may have been little love lost between the two alumni of Lincoln Prison but standards had still to be maintained.

McGarry attended the Dáil session on the 9th September 1922, the first since the Treaty split, and added a dash of the martial by appearing in military uniform.[38] Now a commissioned officer in the nascent National Army, he found himself embroiled, like many of his colleagues, in the internecine conflict that was wracking the country.

At one point assigned to a detachment of soldiers guarding the Amiens Street Railway Station, McGarry was forced to cancel an interview with Hayden Talbot that Collins had set up due to the presence of enemy snipers making travel through the city “inadvisable,” as he put it, with admirable deadpan, to Collins in a phone-call from the station.[39]

On the other side of the War was Frank Henderson. A veteran of the Easter Rising like McGarry, Henderson found himself promoted to O/C of the Dublin IRA Brigade when his predecessor was arrested. His heart not in the fight, Henderson tried to hold back, even after the first batch of executions of anti-Treaty prisoners in November and the subsequent orders for him to assassinate pro-Treaty politicians. “I didn’t like the order,” he said simply, years later.

McGarry may have owed his life to such reticence, at least according to Henderson, who described him being out and about in town and frequently drunk in Amiens Street (McGarry apparently doing more than just guard duty there), with Henderson having to veto requests from his trigger-happy subordinates to kill him and other vulnerable targets then and there.

Although Henderson did not say whether he had had a role in the fatal shooting of Seán Hales TD that December, the fact that he would for the next sixteen years ask his son to say a mass for the dead man would indicate a guilty conscience.

After the Civil War, Henderson would find himself snubbed by Richard Mulcahy. This was apparently due to Mulcahy holding him responsible for Hales’ death…and perhaps for another, equally dark incident, one where McGarry was not so lucky.[40]

‘Incendiary Fires in Dublin’

Tomasina McGarry was upstairs with her three young children at her Dublin home on the 10th December 1922, when there was a knock at the door shortly after 9 am. Startled but suspecting nothing, her mother and sister, who were visiting, went to answer.

Five or six men confronted them. Ignoring the protests that there were children upstairs, the intruders forced the women out into the street at gunpoint and rushed inside. They sprinkled the hall and sitting-room with petrol and set the place alight before running back out. The hall door was slammed behind them, inadvertently locking it and preventing the two McGarry women from re-entering.

Tomasina was oblivious to what was happening on the floor below, only becoming aware that something was very badly wrong when she saw the fire which spread rapidly throughout the house, filling it with noxious smoke.

Between the flames, the door and 7-year-old Sarah’s disabled condition, escape was impossible. All the trapped family could do was to scream out of the window for help. Drawn by the sight of the two frantic women on the pavement, a crowd soon gathered but, as the Irish Times caustically put it: “as is usual on such occasions, suggestions seem to have been more numerous than acts.”

It was only when Sergeant Patrick Smith of the DMP arrived that anything was done. Smith tried and failed to force open the jammed door and had to resort to rushing through the neighbouring house to the backyard. From there, he was able to enter the burning building and, at great personal risk, reached the upstairs room where Tomasina and the three children were huddling together.

Meanwhile, two young men had succeeded where Smith had failed and battered open the front door, dashing up to the sergeant’s assistance. With this collective aid, the family members were removed from their burning home. By the time the fire brigade arrived, the building was too far gone to save and was left a gutted ruin.

Samson in the Temple

Sadie was uninjured and ‘merely’ in severe shock. Tomasina and the other two children, however, had received burns. The mother was driven to Richmond Hospital. She had burns to her hair, face and throat which were painful but not life-threatening. Sarah and nine-year old Emmet had also been scorched on various parts of their bodies. Taken to the Children’s Hospital on Temple Street, their conditions were ascertained as stable.

The attack on the McGarrys was just one of a number headlined by the Irish Times as ‘Incendiary Fires in Dublin’, all of which happened almost simultaneously around 9 am. The tobacco shop owned by James J. Walsh, Postmaster-General of the Free State, was broken into by armed men who “went about their business in the customary way” in setting it alight. Walsh had the luck to be out at the time, unlike the McGarrys or Michael MacDunphy, the Acting Secretary to the Free State Government.

As with the McGarrys, the MacDunphy family was home when intruders sprinkled petrol on the floor to set alight. Mrs MacDunphy was at least given the time to rescue her baby from upstairs while her husband phlegmatically asked the intruders for a chance to set his affairs in order before they shot him.

However, the assailants had only arson, not assassination, in mind and made no move to stop MacDunphy from escaping with his family. The fire brigade arrived in time to save the building from complete destruction, unlike those of the McGarrys and Walsh.

Meanwhile, a store belonging to Jennie Wyse Power, a Free State Senator, had homemade grenades thrown through its windows. Despite the milling crowds on the street outside, no one was hurt when the bombs shattered the windows and destroyed most of the shop fittings. Unlike the other incidents, the building did not catch fire, making Wyse Power the luckiest victim of that morning’s orgy of destruction.[41]

Black Shame

De Valera condemned the attack on the McGarry household, albeit not in very strident tones. Writing to a colleague two days later, de Valera drew a distinction between strikes on offices belonging to Free State officials, which were all very well and good, “particularly if these burnings are done effectively,” and those “as that of McGarry’s which were very badly executed” in addition to appearing “mean and petty” – apparently de Valera’s chief concern there.[42]

He might have used stronger words if he was to know the full end result. Despite the initial optimistic diagnosis for the wounded children, Emmet’s condition worsened. Five days after the attack, he died. At the vote of condolences passed by Dublin Corporation on the 18th December, one of the councillors described the occasion as a “most pathetic one”:

There was black shame on the valour of Ireland, which it would take a long time to wipe out. It was not war, but a stupid attempt to intimidate the expression of opinion by public men, and would avail nothing.[43]

The funeral of Emmet McGarry took place that same day. The cortege, large and impressive, left the Children’s Hospital, and was attended by a considerable number of Cabinet Ministers, Dáil Deputies and other notable individuals. His father was able to attend but Tomasina remained in hospital, still bed-stricken from her burns.[44]

Summary of a Career

The career of Seán McGarry as an Irish revolutionary followed the course of the revolution itself, from resistance to responsibility, from triumph to tragedy. Taken under the wing of Tom Clarke as a young man, McGarry was a witness, as well as a participant, to many of the intrigues and manoeuvres that made coups like the Howth Gun-running and the Easter Rising possible. A willing soldier as well as an able conspirator, McGarry spent much of the Rising by Clake’s side in the GPO, narrowly avoiding death on at least one occasion and helping to cover the escape.

He shared the imprisonment of his comrades and, like many of them, threw himself in the Sinn Féin movement upon his release. He continued on in the IRB, though his rise to its presidency and subsequent withdrawal mirrored the revival and waning of that organisation’s influence. One man neither he nor the Brotherhood could control was Éamon de Valera, and not even a spell of jail together could bridge the gap between the two men.

Although by nature low-key and content to be overshadowed by more charismatic men such as Michael Collins, McGarry played a central role in two public events. The first was his dramatic appearance at the Mansion House on March 1919 while still on the run from prison in an event carefully choreographed by Collins. The second was almost three years later in the Dáil debates over the Anglo-Irish Treaty, where he sparred with de Valera and Mary McSwiney.

For all his service to the cause, McGarry was not to be spared the horrors of the subsequent Civil War. As a commissioned officer in the National Army, he was a tempting target for some among the enemy but the good will of others saved him. Such good fortune did not last forever. His family bore the brunt of the conflict when their home was burnt down, resulting in the death of his nine-year old son.

Sources

[1] Ó Broin, Leon. Revolutionary underground: the story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillian, 1976), p. 180 ; Henderson, Frank (BHM / WS 821), p. 17

[2] Bulmer Hobson Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 13,161/4/1

[3] Dore, Eamon T. (BHM / WS 392), p. 10

[4] Ó Broin, p. 163

[5] Coogan, Tim Pat. De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow (London: Arrow Books, 2015), p. 289

[6] Dore, pp. 10-1

[7] McGarry, Tomasina. National Military Service Pensions Collection (Ref: MSP34REF60225) p. 46

[8] Ó Broin, p. 182

[9] Irish Times (quoting from the Evening Herald), 05/03/1919

[10] Lynch, Michael (BHM / WS 511), p. 89 ; Dunne, Declan. Peter’s Key: Peter DeLoughry and the Fight for Irish Independence (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), p. 128

[11] McMahon, Liam (BHM / WS 274), pp. 6-7

[12] Lynch, pp. 89-91

[13] McMahon, pp. 11-3

[14] Lynch, pp. 92-4

[15] Ibid, pp. 94-5

[16] Yeates, Pádraig. A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919-1921 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2012), p. 27

[17] Ibid, p. 79 ; White, Laurence William, ‘McGarry, Seán’ (1886-1958) Dictionary of Irish Biography (Royal Irish Academy, general editor McGuire, James)

[18] Irish Times, 07/12/1922

[19] McGarry, Seán (BMH / WS 368) ; McGarry, Seán. National Military Service Pensions Collection (Ref: 24SP5125), p. 14 ; ‘McGarry, Seán’, Dictionary of Irish Biography

[20] Ó Broin, p. 184

[21] McGallogly, John (BHM / WS 244), pp. 22-3

[22] Daly, Patrick G. (BHM / WS 814), p. 40

[23] Coogan, pp. 198, 712

[24] Florence O’Donoghue Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 31,250/2

[25] Talbot, Hayden (preface by De Búrca, Éamonn) Michael Collins’ Own Story (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2012), pp. 44, 190-2

[26] McGarry, Tomasina. National Military Service Pensions Collection (Ref: MSP34REF60225) p. 36

[27] Ibid, p. 40

[28] Ibid, pp. 61, 50

[29] De Burca, Padraig and Boyle, John F., Free state or republic?: Pen pictures of the historic treaty session of Dáil Éireann (Dublin: The Talbot Press, 1922), p. 42

[30] Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922, 06/01/1921, p. 209. Available from the National Library of Ireland, also online from the University of Cork: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/E900003-001.html (last accessed on 07/12/2016)

[31] Knirck, Jason K. Imaging Ireland’s Independence: The Debates over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 (Lanham, Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers Inc. 2006), p. 114

[32] Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, pp. 250, 256

[33] Knirck, pp. 154-5

[34] Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, p. 210

[35] Ibid

[36] Ibid, p. 211

[37] Irish Independent, 11/01/1922

[38] Irish Times, 11/09/1922

[39] Talbot, p. 44

[40] Henderson, Frank (ed. by Hopkinson, Michael) Frank Henderson’s Easter Rising: Recollections of a Dublin Volunteer (Cork: Cork University Press, 1998), pp. 7-9

[41] Irish Times, 11/12/1922

[42] Coogan, pp. 344-5

[43] Irish Times, 19/12/1922

[44] Ibid

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History Statements

Daly, Patrick G., WS 814

Dore, Eamon T., WS 392

Lynch, Michael, WS 511

McGallogly, John, WS 244

McGarry, Seán, WS 368

McMahon, Liam, WS 274

Books

Coogan, Tim Pat. De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow (London: Arrow Books, 2015)

Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922. Available from the National Library of Ireland, also online: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/E900003-001.html (last accessed on 07/12/2016)

De Burca, Padraig and Boyle, John F., Free state or republic?: Pen pictures of the historic treaty session of Dáil Éireann (Dublin: The Talbot Press, 1922)

Dunne, Declan. Peter’s Key: Peter DeLoughry and the Fight for Irish Independence (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

Talbot, Hayden (preface by De Búrca, Éamonn) Michael Collins’ Own Story (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2012)

Henderson, Frank (ed. by Hopkinson, Michael) Frank Henderson’s Easter Rising: Recollections of a Dublin Volunteer (Cork: Cork University Press, 1998)

Knirck, Jason K. Imaging Ireland’s Independence: The Debates over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 (Lanham, Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers Inc. 2006)

Ó Broin, Leon. Revolutionary underground: the story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillian, 1976)

White, Laurence William, ‘McGarry, Seán’ (1886-1958) Dictionary of Irish Biography (Royal Irish Academy, general editor McGuire, James)

Yeates, Pádraig. A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919-1921 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2012)

Newspapers

Irish Independent

Irish Times

National Library of Ireland

Bulmer Hobson Papers

Florence O’Donoghue Papers

National Military Service Pensions Collection

McGarry, Tomasina. Ref: MSP34REF60225

McGarry, Seán. Ref: Ref: 24SP5125

Thanks for this. Sean McGarry was my great uncle (x 3). My son needs something interesting to write about his family history for a school project and I thought about Sean’s legacy. This will be perfect to fill in some blanks. We had heard murmurings about the jail break and house fire in our family folklore, but this rendition is very well research. Thank you so much.

LikeLike