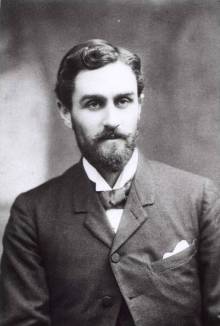

‘Richard Morton’

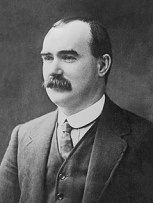

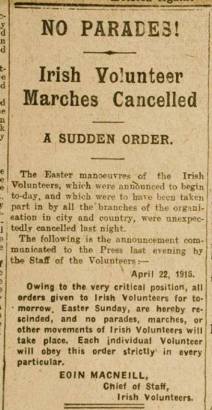

It was just another morning for Constable Bernard Reilly as he waited out his shift at Ardfert Station, Co. Kerry, on the 21st April 1916, Good Friday, when a man came by to report a boat seen down by Banna Strand. Reilly passed this on to his superior, Sergeant Tom Hearne, who went to investigate with Constable Robert Larke.

All three were members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the police force tasked with upholding law and order throughout Ireland – British law and order, that is. It was a centuries-old state of affairs that some, unbeknown to Reilly and his colleagues, were planning to change and soon – within the next few days, in fact.

Hearne and Larkin returned to the station at 11 am with a horse and cart, on top of which was a boat. As well as the abandoned vessel, the two RIC men had found on the beach three Mauser pistols, some ammunition, two or three signalling lamps and several maps, including one of the locality. Talk about town was of three strangers seen walking inland from the direction of Banna Strand, presumably having come in off the boat in question.

Sergeant Hearne sent a report via the Ardfert post office to the RIC headquarters in Tralee and then took Larke and Reilly to search for the rumoured trio. After fruitlessly knocking on the doors of houses in the vicinity, Hearne, accompanied by Reilly, decided to give McKenna’s Fort a try. While the sergeant treated himself to a smoke outside, Reilly entered the Fort, if that was not too grand a name for the overgrown, long-abandoned rath.

As he did so:

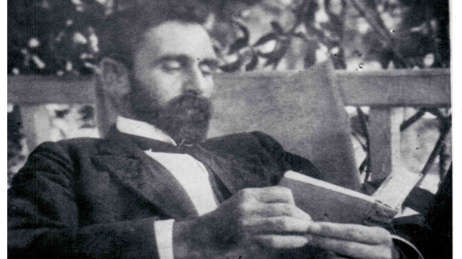

…a man approached me from the shrubbery. He was a tall gentleman. He looked foreign to me and not generally the type one meets in a street. There was nothing unusual about his clothes. He wore a beard and had more or less an aristocratic appearance.

This regal-looking individual introduced himself as Richard Morton, a writer from England who was in Kerry researching for a book he was writing on St Brendan the Navigator, a local celebrity from antiquity. As he spoke, Morton fiddled with a sword-stick, drawing the blade in and out, while glancing over his shoulder as if looking for someone.

So that there would be no misunderstanding, Reilly advised the other man to refrain from unsheathing his weapon or else he would shoot with his own. Actually, the rifle Reilly carried was unloaded but there was no need for the twitchy visitor to know otherwise.

When Sergeant Hearne appeared, Morton repeated his story to him. Not wholly convinced by this, Hearne asked him if he could come with them to the station, to which the self-proclaimed Englishman agreed. He had probably guessed he had little in the way of choice on the matter.

The two policemen and their surprise acquaintance walked to the public road, about seventy-five yards from the fort, where they came across a boy called Martin Collins, who was driving a pony and trap. Commandeering a ride, if temporarily, Reilly put Morton on the trap and, sitting firmly beside him, rode off, with Hearne and Collins waiting behind.

Reilly took him to a farmhouse where lived Mary Gorman, who had first spotted the three mystery men leaving from Banna Strand while she milked the cows. After Gorman identified Morton as one of the trio, Reilly returned with him to where Hearne and Collins were waiting.

The RIC men gave the pony and trap back to the boy, who, his curiosity piqued, followed the small group of Hearne, Reilly and Morton as they walked the mile back to Ardfert Station. It was by then midday. Collins handed a slip of paper to Reilly, which their new friend had dropped. Written on it was part of a code – useless in itself, but something which would later serve as evidence in a trial that resulted in the sentence of death for ‘Richard Morton’ or, rather, Sir Roger Casement.[1]

Germany Calling

For Casement, it was a strangely anticlimactic end to an adventure that had promised so much at the start. “At last in Berlin! The journey done – the effort perhaps only begun!” he wrote in his diary in October 1914. “Shall I succeed? Will they see the great cause aright and understand all it may mean to them, no less to Ireland?”[2]

The answer, initially, was ‘yes’; his new allies did indeed see the worth of the mission Casement brought before them. A succession of German officials listened sympathetically as he spoke of his dreams of enlisting their nation’s help in securing the freedom of his own, though their sanguinity could give even him pause. When Casement warned Baron Wilheim von Stumm that Britain had the means to prolong its current war with Germany for years, the Director of the Political Department at the Foreign Office laughed.

“What can she do to us?” von Stumm replied. “Her fleet is become a laughing stock.”[3]

By April 1916, almost two years later, Casement was straining to escape his host country. “My last day in Berlin! Thank God!” Even a possible fate at the end of an English noose did nothing to deter him. “Oh! To see the misted hills of Kerry and the coast and to tread the fair strand of Tralee!”[4]

He had already been informed, on the 30th March, about the planned uprising in Ireland. As the Germans initially declined to provide any weapons or men to help, Casement could foretell only disaster. “I said I could guarantee no revolution and that I sincerely hoped there would be none!”[5]

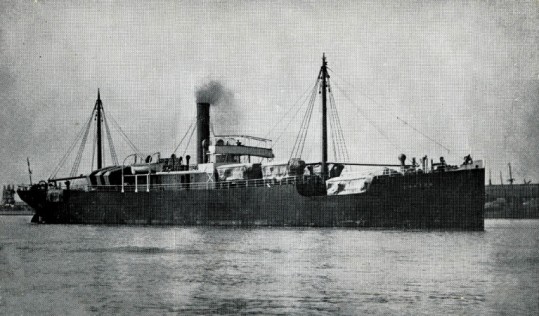

The next day, he was wheezing in bed, struck down by a lung congestion, but no less committed to returning, if only to put a stop to this rebellion-in-the-works. That the Germans had at last consented to provide help, in the form of a steamer loaded with weapons for Tralee Bay, on Easter Monday, but only on condition of the Irish rebels being out in the field already on the Sunday, was enough to send Casement into a rage: “The utter callousness & indifference here – only seeking bloodshed in Ireland.”[6]

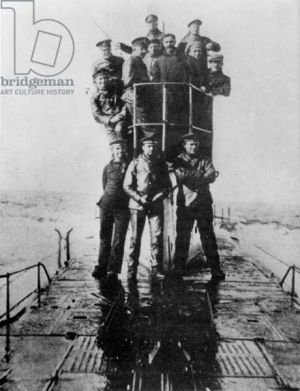

The only thing left for him to do was board the submarine provided for him and put Baron von Stumm’s lofty dismissal of the Royal Navy to the test.

Casement was not looking forward to the journey – twelve days, he reckoned, inside a stinking, suffocating confinement – but it would be worth it once he reached his homeland. He had been assured they would make it in time but Casement nursed his doubts: “My first fear is that we shall never land – but be kept off the shore until the ‘rebellion’ breaks out.”[7]

And that was the last line in his diary, though there was still much to happen. Too much, and also too little.

Homecoming

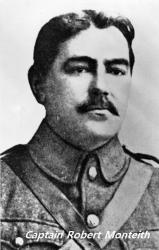

Accompanying Casement on his return home were Captain Robert Monteith and Sergeant Daniel Bailey. The former had come to Germany to assist Casement with setting up the ‘Irish Brigade’, made up of Irish POWs, while the latter was one of these said recruits, before the project was set aside as a failure.

The Germany Navy had at least rowed back on its original demands for an Irish rebellion to have broken out the day before the weapons shipment landed. Instead, a vessel was now set to arrive between Holy Thursday, the 20th April, and Easter Sunday, the 23rd, the window of four days being regarded by the German planners as sufficient to account for the vagaries of weather. As the insurrection was timed for the Sunday, according to the missives from the revolutionary leadership in Dublin, the haul of 20,000 rifles should arrive in time for the rebels to be thus equipped for when they set forth.

The Germany Navy had at least rowed back on its original demands for an Irish rebellion to have broken out the day before the weapons shipment landed. Instead, a vessel was now set to arrive between Holy Thursday, the 20th April, and Easter Sunday, the 23rd, the window of four days being regarded by the German planners as sufficient to account for the vagaries of weather. As the insurrection was timed for the Sunday, according to the missives from the revolutionary leadership in Dublin, the haul of 20,000 rifles should arrive in time for the rebels to be thus equipped for when they set forth.

As he listened to these arrangements being laid out at the Admiralty in Berlin, Monteith was dismayed at what he considered to be a pitifully inadequate donation of weapons, and said as much. It was brutally clear, however, that that was all the Irish cause could expect from its ‘gallant allies’. At least a bedridden Casement was elated when Monteith brought the news to him – any development was better than none at this point.[8]

Nonetheless, the three Irishmen found much to brood over as the U-boat took them over the northern tip of Britain and down the Irish west coast. They had been away for so long that they knew little about how things stood in their country. Nor could they be sure about the Aud – the steamer carrying the rifles – arriving in time, if at all, and whether the rebellion Casement dreaded would happen regardless.

When the U-boat passed the mouth of the Shannon, on the evening of the 20th April, the trio watched from the conning tower, peering into the starless night for the pilot boat that was due to guide them but its twin green lights – the prearranged signal – never materialised.

Other lights came and went but never the ones they so desperately sought. Neither did the Aud appear, though the Irishmen had spotted it earlier in the day. Finally, the submarine captain announced that they could wait no longer and set the course for full speed towards Tralee Bay. As the three Irishmen prepared to disembark, Monteith loaded his pistol, and then tried teaching Casement how to use his.

“It is quite possible we may either kill or be killed,” Monteith warned but Casement had never handled a gun before and, besides, he appeared too sick to be of any use in a fight. Monteith suggested some sleep but, what with all the worry, that was also unlikely to happen.

Instead, they gloomily discussed their odds. While they had evaded British patrol ships, Casement did not think the German steamer would be so lucky. Other than the loss of the much-needed weaponry, such a find, Casement feared, would almost certainly put the authorities on their guard.

Further talk was curtailed by a German officer telling them that it was time to go ashore. When Monteith saw the size of the boat that was to carry them, he had the presence of mind to request three lifebelts. Casement sat in the stern, Monteith the bow, and Bailey in between as the boat was lowered onto the lazily rolling waves. Its duty done, the submarine receded into the dark, leaving the three companions to face the unknown.[9]

Hunting for Help

As the captain had refused them a motor, lest the sound betray the German presence – concern for the Irishmen was not so forthcoming – the tiny crew had to make do with rowing. Somehow they avoided drowning, though just about. A landlubber at heart, Monteith pushed his oar too deeply and went overboard, head first, before Bailey hauled him back.

When they were close enough to shore, Monteith jumped out, standing up to his waist in the water while Bailey unloaded, first their equipment and then Casement, who was practically an invalid by then. Monteith tried scuttling the boat but the wood was too hard for his knife, the only tool he had at hand, and so he abandoned the task.

But the wretched tub was not yet finished with me. As I was about to leave, a wave struck it, and drove it sideways on top of my right foot. This wrenched my ankle, adding a little to my general discomfort. I scrambled away, and went up to the beach.

All three men were stretched out on the sand, soaked to the skin, bereft of sleep and food save for the little they could keep down during the past few days of seasickness. Casement looked the worst, being barely conscious, and Monteith had to make him move about so as to restore some semblance of circulation to his limbs.

With dawn fast approaching, the trio knew they had to act. Given the perilous state of Casement’s health, it was decided to leave him in hiding while the other two walked into Tralee, their plan from there being to procure a motorcar for Dublin. So as to not stand out when reaching civilisation, they buried their Mauser pistols, ammunition belts, field glasses and the rest of the equipment, save their overcoats, in the beach.

Striking inland, they stumbled into some bogland, as if they were not damp enough already. Sunrise gave them some comfort, as well as a better view, and, coming to firmer land, they found a ruined old castle which they had been considering as the best place to leave Casement. Seeing it in the cold light of day, however, the group were forced to rethink that plan – Monteith did not think the castle large enough to hide a cat – and so it was agreed to keep going and find a better site.

As they passed a farmhouse on the road:

Looking over the wall, we saw a young girl, her hair tousled and untidy, blinking at the sun and leaning on a half door. She saw us, and stared in a manner that showed it was unusual for strangers to pass along that road so early in the morning.

Considering their bedraggled state, it was hardly surprising that they would attract attention, from Mary Gorman or anyone, at any time of the day. The trio were more careful when a cart rumbled their way on the road. Crossing the fence to the side, they hid among the bushes until the cart passed, its two passengers seemingly none the wiser.

Half an hour later, they had a second bit of good fortune when finding the remnants of an ancient hill-fort, thick with shrubbery. That seemed an opportune place to leave Casement, better than the previous choice in any case, and so the other two pressed on while their comrade recuperated as best he could.[10]

Tralee

Following the shore road, Monteith and Bailey were able to cover the eight miles to Tralee in good time. Carefully avoiding the RIC station at Ardfert – whose occupants would soon be paying a visit to Casement in McKenna’s Fort – they saw no one except a surly farmer, who did not bother to return their greeting, and then a sole policeman, who took one look at the pair before continuing on his way. The two men breathed a sigh of relief at this timely piece of official negligence.

It was 7 am on Good Friday morning when they reached Tralee. There were some people about but no shops open, save for a few newsagents. Both Monteith and Bailey were so ignorant of the area that they decided their only chance lay in finding someone who wore a tricolour or, failing that, a newsagent that sold the more radical papers in the hope that their sympathies were as republican as their stock.

They had no such luck until coming across a hairdresser’s saloon, with posters outside of The Irish Volunteer and The Worker’s Republic, exactly the sort of titles they were seeking. The saloon was not open but the neighbouring door was and so the pair took the chance of accepting the invite of a shave from the man standing there:

We entered and found ourselves in a news agent’s shop, which was lighted by the doorway only as the shutters were not yet off the windows. The proprietor, whose name was [George] Spicer, informed me that he worked both the news agent’s and hair dressing shops, and that his son would be down in a minute to shave me.

Having gone too far to back away now, Monteith asked Spicer for the name and address of whoever led the Irish Volunteers around there, adding that he and his companion were on important business concerning them. As proof of his urgency, he pointed to their wet clothes.

After thinking it over, Spicer called his son down and told him to go fetch Austin Stack, the commander in question. All Monteith and Bailey could do in the meantime was wait: “We were counting the minutes as we thought of poor Casement away out in the old fort, wet, cold and hungry, waiting for a car that never came.”

After thinking it over, Spicer called his son down and told him to go fetch Austin Stack, the commander in question. All Monteith and Bailey could do in the meantime was wait: “We were counting the minutes as we thought of poor Casement away out in the old fort, wet, cold and hungry, waiting for a car that never came.”

When Stack arrived, he was accompanied by his aide, Con Collins, who had met Monteith before and was able to vouch for him to his commandant. Monteith gave them the basic details of Casement’s plight, including his need to go to Dublin and get in touch with the leadership of the Irish Volunteers there. Stack promptly dispatched a man to find a motor car for that purpose.

When Monteith asked after the German ship with the arms, Stack replied that his orders were that the vessel in question was not due to reach Tralee Bay until Easter Sunday, in two days’ time:

He had no information of the ship being already in the bay. I urged that he send a pilot out at once and told him what the ship carried. I told him there was no artillery coming, neither officers nor artillery men. Stack made no comment beyond saying that as far as his orders went, the ship was not to come in until Sunday night.[11]

In fact, there had been talk of a strange vessel sighted off Fenit Point on the previous day, Thursday, leading to a trusted Volunteer, William Mullins, being sent there to investigate. After talking to a few locals, Mullins returned to Tralee to report his belief that the rumours had been entirely spurious.[12]

The Larger Project

And now these two outsiders had appeared out of nowhere to tell Stack that his orders from Dublin were wrong. That they were there at all put him in an awkward position, threatening as they did, with their mere presence and unsolicited updates, the plans for the Rising in Kerry.

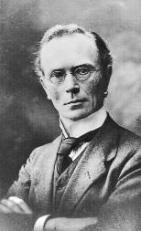

For Stack, the event had been a long time in the making, ever since he was summoned to Dublin, sometime in late 1915 or early 1916, for an interview with Patrick Pearse, on the grounds of the latter’s school of St Enda’s. Accompanying Stack was Alf Cotton, a Belfast native who had been sent to Kerry by their mutual superiors to help Stack lay the groundwork for….something.

That something was revealed by Pearse to be a full-scale insurrection of the Irish Volunteers throughout the country, timed for the Easter Week of 1916. A series of parades would provide cover for the different units to muster, after which they would act on their respective instructions.

Those for the Tralee Company were more elaborate than most. Besides the usual targets – such as the RIC barracks, the post office and the train station – the Kerry Volunteers were to greet a ship carrying German arms at Fenit Pier and then help with the logistics of transporting the cargo, via commandeered trains, along the west of Ireland, where the Volunteer companies on the route would take their share.

Concerned about the difficulties the vessel in question would face, from the dangers of fog or storm, to running the blockade of British warships, Cotton suggested alternatives, such as landing the supplies in smaller amounts at different points, or even the use of Zeppelins to bypass the Royal Navy altogether, but Pearse insisted that the arrangements had already been set in motion.

Pearse also stressed the need for absolute secrecy. Information was to be limited to a select few, only when necessary, and never more than needed. Previous rebellions had floundered from a fatal leakage of intelligence, a negligence which Pearse was determined would not be repeated this time.

“Secrecy was to be preserved up to the very last minute,” as Cotton described. “Much depended on the element of surprise both for our local activities and for the larger project.”[13]

Pearse reinforced these instructions on a visit to Tralee, three or four weeks before Easter Week. In particular, Stack was to keep his men on a tight leash, at least until Easter Sunday, the designated date, lest any premature deed tip their hand to the British authorities.[14]

‘The Game is Up’

This was something Stack kept at the forefront of his mind during those hectic hours, when he struggled to fulfil the duties bestowed on him by Pearse, while juggling with the sudden demands thrust on him by Monteith and Beverley. As his widow put it:

Austin was blamed by some for not trying to organise a rescue of Sir Roger Casement and I know he felt very sore about it, but he always said his orders were definite that no shot should be fired before the start of general hostilities on Easter Sunday and he knew well that any fracas that might take place in Tralee would frustrate all the plans made for the Rising.[15]

But first Stack made an attempt to retrieve Casement from where the newcomers said they left him. When the car Stack requested pulled up outside, he and Collins got in, along with Bailey, while Monteith stayed behind. As a guide, however, Bailey left something to be desired, ignorant as he was of the locality, with only the information that Casement was “somewhere on Banna Strand” to offer.

Which was better than nothing. Stack recruited Maurice Moriarty, a Tralee Volunteer, to put his profession as a chauffeur to use in driving him, Collins and Bailey to Banna Strand, taking care to avoid the police base at Ardfert. When they came across a horse and cart, managed by two RIC men from the opposite direction, Stack asked Bailey if the boat on top was his.

When Bailey replied that it was the same, Stack could only exclaim: “Oh, God, lads, the game is up.”

Worse, there were about twenty policemen posted about Banna Strand, obviously on the lookout. Finding Casement suddenly became the least of their concerns. “The game is up,” Stack repeated, according to Moriarty. “What are we going to do now?”

As a RIC officer, Sergeant Daniel Croly, came their way, it was quickly agreed inside the car that they would pose as innocent sightseers. It was then that one of their tyres burst, prompting the startled sergeant to accuse them of firing a gun at him. The police were clearly on edge, though how much the authorities knew was yet uncertain.

Bluffing and Brazening

When Croly had calmed down:

He then got curious and demanded an explanation of our presence on the Strand. I [Moriarty] told him my passengers were visitors on holiday, they wished to travel along the sea coast, and that I was under the impression it was possible to get to Ballyheigue by following the beach.

The sergeant did not seem wholly convinced by this but left them alone long enough for the four men to change their tyre and drive away to Lawlor’s Cross. Croly followed them there on a bicycle and continued his questioning, such as whether they had heard anything about a boat landing that morning.

When Stack replied that he did not, Croly continued: “Yes, we got the boat and we got our man, too.”

When the policeman next asked what he would do if put under arrest, Stack threatened to make a fight of it. After some more verbal toing-and-froing, Croly finally searched the car and, finding nothing of note, let them go. Even that was not the last the Volunteers saw of the sergeant, for when they drove on to Ballyheigue – to go anywhere else would have only incited more suspicion – and called into a pub:

After we were there some time I [Moriarty] saw Sergeant [Croly] going into the Post Office. I called Stack’s attention to this and Stack said, “Yes, I saw him. I suppose he is ‘phoning all over Ireland. We are done now.”

Stack’s gloom seemed justified when they travelled on to Causeway village, to be confronted by an RIC patrol on the alert for their car. Collins was searched when he got out and taken away to the barracks when a Webley revolver was found on him.

Stack made a tougher show of it, admitting that he had a loaded automatic, along with spare ammunition and some documents, but that, when asked if he had the paperwork for the gun: “No Irishman needs a certificate these days to carry firearms.”

When the sergeant in charge weakly admitted this was the case, Stack boldly went to the barracks, gun still in hand, and came out a few minutes later with Collins. Stack had brazened his way and that of his comrades out of trouble but it was clear now that the risks of keeping Bailey, a stranger to the area, around for any longer were too great. After they drove out of Causeway, they stopped at Ballymacaurin village to leave Bailey at the house of a Volunteer.

The remaining three returned to Tralee, their journey done, with Stack warning the others to deny anything if asked. As Moriarty left to park the car, he noticed an increased RIC presence on the streets. He had just finished dinner at home when another policeman came to ask about his passengers that day. Moriarty stuck to his script and insisted that the others had merely been tourists.[16]

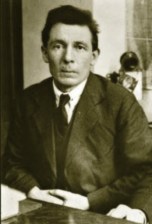

Austin Stack

Stack and Collins were likewise questioned together at the former’s house by a constable, with Stack waxing indignant at how their trip that morning had been ruined by intrusive peelers. After sharing a light meal, Collins left to see a friend in town, while Stack went to the Rink, a hall rented by the Irish Volunteers for their activities.

Stack had previously called a meeting for there, ostensibly to organise a parade, set to be held on the Sunday, in two days’ time. In reality, the event was intended only as an excuse for the Volunteers to muster, just before the Rising was due to begin, a motive Stack had been keeping to himself. True to his instructions for absolute secrecy until the last possible moment, he continued the charade as he sat down to work out the details of the phoney parade with the other officers in attendance.

The session was almost concluded when Collins’ friend in town, Michael O’Flynn, came in to take Stack aside. O’Flynn told him that he had been with Collins when the RIC came to arrest the latter, and he was now passing on the other man’s request for Stack to see him in the station. Stack agreed to do so and returned to the meeting, when another piece of bad fortune arrived, courtesy of a Volunteer who had come from Ardfert on a bicycle:

I saw this scout immediately and the news that he had for me was to the effect that the Ardfert police had brought to the barracks, as a prisoner, a tall bearded man. At once I knew that this was Sir Roger Casement.

When Stack broke this news to the others in the Rink, the immediate response was a call to attempt a rescue. It was not something Stack could allow, given his orders – as he now revealed – to keep everyone quiet until the appointed time on Sunday. After dissuading the rest from taking any rash action, Stack next arranged for two couriers to be sent to inform Dublin of the developments, from Casement’s arrest to the premature arrival of the German ship.

The latter was a particular problem in Stack’s mind:

I had the view that it would be almost impossible for the vessel to escape on account of the capture of Sir Roger Casement, as the English were now certain to be keeping a sharp look-out everywhere about that part of the coast.[17]

The two messengers knew exactly where to go when they reached Dublin. Eoin MacNeill may have been Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers but the true power of the forthcoming revolution had gathered inside Liberty Hall.

James Connolly, Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke and several others listened as one of the Kerrymen, William Mullins, delivered his report about Casement’s arrest and how, according to Casement, there would be arms coming from Germany but no soldiers. Mullins knew nothing about any uprising, though he must have suspected something upon seeing about sixty or seventy men in a room inside Liberty Hall, busily preparing gun cartridges.

If his listeners were fazed at the news, they did not show it. “There will be no change in the original plans,” Pearse told Mullins to pass on back to Kerry.[18]

Surprises

Stack, meanwhile, had gone to the RIC barracks as requested, where he asked to speak to Collins. The constable on duty excused himself after asking the visitor to remain in the room, and there an unsuspecting Stack was waiting when, a few minutes later, the constable returned with several of his colleagues to put him under arrest.[19]

It is unlikely that the police were aware of how effectively their capture of Stack had decapitated the Kerry Volunteers, the vast majority of whom were only dimly aware, at best, that anything was in the works. “Apart from rumours and whisperings of things to happen,” remembered Peter Browne, captain of the Scartaglin Company, “the average Volunteer had no official inkling of anything big coming off.”

The man best positioned to take over from Stack was Alf Cotton, the Volunteer organiser from Belfast, but he was nowhere to be found. Browne believed he had returned to his home city earlier in the year, apparently to take care of his sick mother. Cotton would be accused of being intentionally absent by Paddy Cahill, who, despite being next in line as battalion adjutant, knew only a little more than the rank-and-file.

When Browne interviewed him as part of a history project, “Paddy Cahill told me that he had no knowledge of the major plans for Kerry when Stack was arrested.” While Cahill knew there were weapons being shipped in, he had believed, like Stack, that they would not be due until Easter Sunday.

“It later transpired that the sinking of the Aud had completely upset the plans locally and nationally,” Browne wrote. “What the plans for this were never came to light.”

It says much about the confusion surrounding the Easter Week of 1916, even years later, that when Browne suggested he write up his version of events, Cahill replied that he had done so already and sent it to Stack’s widow for the book she was writing about her husband. Browne asked Winifred Stack about it, shortly after Cahill’s death, only to be told that she had not received any such information from him.[20]

Hiding Out

Monteith was better informed than most in Kerry; he, at least, knew there was supposed to be a Rising. But, in other respects, he was as woefully ignorant as any.

When the two messengers went to Dublin, Monteith assumed they were making for Eoin MacNeill as Chief of Staff. It never occurred to him that the couriers would go instead to Liberty Hall and bypass the chain of command as he knew it. Nor did his Kerry compatriots make any effort to bring him up to date.

He was a man groping in the dark, as he later described it, a fact that continued to rankle by the time he put pen to paper for his memoirs: “These men with me knew that my life was not worth a moment’s purchase, yet they did not enlighten me.”

By Friday night, Monteith had learnt from the evening papers about the arrests of Stack and Collins, along with the discovery of the boat by which he and the other two had left the U-boat. “It was a peculiar report to read of one’s own adventures,” he mused.

With little else to do until the big event on Sunday, Monteith laid low in a friendly house. That the Volunteers had thought to post an armed guard inside was of some comfort, though otherwise the news on Saturday morning was hardly reassuring: British soldiers had come into Tralee by train, while armed RIC men stalked the streets of the town.

Several times, an enemy patrol would pass by the house, with Monteith watching anxiously from behind a window curtain until they had gone. When he finally ventured out, on Saturday night, it was in a workman’s garb, complete with a greasy cap over his head and chimney soot on his face.[21]

“If the police stop us or try to arrest you,” said one of the Kerrymen to their charge, “we will open fire.”

He meant it as a reassurance, but Monteith was unimpressed. He had not made it thus far without appreciating the virtue of caution, after all. “I am the officer. I have more authority,” he replied tartly. “There is to be no firing.”[22]

Assuming Command

Around a dozen other men were waiting for them at the Rink, standing to attention and under the command of Paddy Cahill. At least, Monteith assumed Cahill was in charge, until the Kerryman told him that the authority was now his. Orders had come in to that effect, said Cahill, though he was coy when asked on whose authority. Monteith tried to talk himself out of it, arguing that he knew nothing about Tralee, either the area or its men, but Cahill was adamant.

Finally, Monteith gave in and assumed responsibility, however flabbergasting he found it. “Here was an amazing situation,” he wrote in his memoirs. “An officer, my senior, ordering me to take command, while he reverted to the ranks.”

At least he had his experience as an officer in the British Army to fall back on. Unfortunately, as he talked to his new subordinates in the Rink, it was apparent that the rest of the Irish Volunteers had not had the same level of training. Neither did they know much about what was to be done besides a vague notion of seizing the military barracks, RIC station, telegraph office and train station, before marching to the coastal village of Fenit and unloading the promised German arms from there. Any further details had been known only by Stack, and he was gone.

And then there was the issue of numbers. Monteith estimated he would have three hundred men at his disposal, of which only two-thirds were armed. Word was that reinforcements would join them from Dingle but no one could confirm this. Against them would be five hundred British soldiers and about two hundred policemen, and now with the advantage of surprise lost.

“I knew I had a full day’s work ahead of me,” Monteith recalled laconically.[23]

Easter Sunday

Monteith sent the officers home for the night while he stayed in the Rink and brooded on what to do. Holy Saturday passed into Easter Sunday, the day set for the Rising, and Monteith received word that at least one of the companies outside Tralee – he spared naming the unit in question for posterity – would not be making the rendezvous with destiny, the Volunteers having decided among themselves that, in light of the absence of German assistance, there was little point in continuing.

Not so doleful, Monteith yet had hope, however slim, in the arms-ship reaching them. To that end, he sent out scouts to Fenit Point, where the vessel was to come – if at all – and another in a car to Killarney in the hope of coordinating with the Irish Volunteers there should the arms arrive and, if so, with the aim of opening the way to their comrades in Limerick. “The Limerick men, I had been told, were to hold the line of the Shannon, what section I did not know, nor for what reason.”

And these questions were to remain unknown, for the messenger to Killarney never returned. The Fenit scouts did, to report the presence of two Royal Navy warships in the bay. So much for the German vessel then, for there was no hope now of it breaking through.

At least the two messengers had reached their destination of Dublin, as shown by the return of a verbal message from James Connolly, to the effect that everything was alright and to continue as planned. What these plans were, however, remained sketchy, a situation his Kerry subordinates were of little help in remedying, often seeming to regard him with suspicion, to judge from their evasive, distinctly unhelpful responses to his queries.[24]

In that regard, Monteith was not imagining things. “Cahill did not trust Monteith as he or none of us knew anything about him,” remembered one of the men at the time.[25]

‘The Most Wonderful Part’

A glimmer of hope came with the only-half-expected Dingle contingent, at about 11 am, whose Volunteers had walked the thirty to forty miles to Tralee. Next were the Ballymacelligott men, adding their forty numbers to the Dingle hundred and twenty, while women from Cumann na mBan joined them to prepare some breakfast. Monteith now had about three hundred and twenty men to his command, although only two hundred were armed, either with a rifle or revolver.

Still, despite his professional misgivings, Monteith could not help but be touched by the display:

The most wonderful part of the whole thing, and perhaps the most tragic as I saw it, were boys of fourteen to seventeen years of age, marching in without as much as a walking stick with which to defend themselves, but all in the sure and certain hope of gaining a glorious victory over the usurping English.

Monteith told the Dingle captain to send out his charges with money to purchase supplies, enough for two days, and then be back at the Rink for 1.30 pm, half an hour before they would begin the Rising that would shake an empire. When Monteith asked if they were ready, the Dingle man replied: “Yes, in more ways than one, they have all been to the altar.”

It had started raining by the time a stranger, his face obscured by his collar upturned against the downpour, arrived at the Rink. When Monteith got a better look, he recognised him as Patrick Whelan, an acquaintance of his from their time together in the Limerick Volunteers. Monteith was eager to ascertain how things stood in Limerick but Whelan – after his surprise at seeing Monteith, thinking him still in Germany – brought word that abruptly rendered their plans irrelevant: all operations were to be cancelled. The Rising was over before it had even begun.

“Here was a pretty mix-up,” as Monteith put it, with masterly understatement.[26]

The End of Easter Week

After all the drama and tension of the past few days, Easter Monday was oddly quiet. By the evening, word of fighting in distant Dublin had begun to circulate, galvanising some of the Kerry Volunteers into mobilising that night, at the Rink again. Even then, caution ruled and most of the attendees were dismissed, with only twenty remaining to guard the hall for the night and to receive the scouts who were bringing messengers from the other units around Kerry.

With no one aware of the situation or sufficiently placed, after the loss of Stack and Cotton, to know what to do, all the men could do was wait…and wait.

“Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday passed off quietly,” remembered Peter Browne. “The Rink was full of Volunteers at all times and wild rumours were afloat about Dublin and other places. On Friday there were rumours of a surrender in Dublin.”

These defeatist reports were initially dismissed but, later in the day:

They were confirmed at Volunteer headquarters on Friday night. A meeting was arranged between the local British military officers and some Tralee citizens, including the clergy, which was attended by Volunteer representatives who agreed, in order to avoid arrests, to surrender all arms and ammunition to the military on or before Saturday.

At least the Kerry Volunteers, when this requirement was announced to them on parade on Friday night, could take some measure of defiance in denying the enemy the use of their weapons as the men grabbed hammers or sledges to smash the barrels of their guns. Browne was an exception as he instead smuggled his rifle out of the Rink beneath his coat. Four years passed before he could finally put it to use, in 1920, during an attack on a RIC barracks.[27]

‘One Great Tragedy’

But, for now, it looked as if the movement was beaten. If the Kerry Volunteers had assumed that rolling over in submission would be the end of it, they were rudely disabused the following week, when it was reported, on the 11th May:

A Tralee message says that wholesale arrests of prominent members of the Sinn Fein organisation were effected throughout Kerry on Tuesday [9th May]. In Tralee, cavalry, infantry, and police turned out and halted opposite each house where arrests were made. Excitement ran high, but there was no disturbance.[28]

Such coordination by the RIC and British military showed that the authorities were taking no chances. When William Mullins saw a woman curse some prisoners being led away by British soldiers, he grabbed the Union Jack from her hands and tore it to pieces. He was arrested the next day, and taken to join the other detainees in Tralee Jail.[29]

By then, Stack and Collins had already been removed from the gaol. Since his confinement there on Easter Saturday, Stack had remained out of the loop, save when two friends visited him on Monday to inform him of the cancellation order, leaving Stack to assume that that was the end of their venture.

He was still oblivious when he and Collins were ordered out of their cells on Easter Wednesday, marched to the train under heavy escort and transferred to Cork, and then Queenstown (now Cobh), before taken by steamer to Spike Island. The next three weeks were spent in the purgatory of solitary confinement, ignorant of the world beyond until, on the 13th May, the pair were transported to Dublin.

While en route, their train stopped in Cork. The previously empty carriage they were held in was soon filled with prisoners from the Cork Volunteers. From them, Stack and Collins were able to learn of how rapidly the revolution had moved in their absence:

We were told of the Rising which had taken place in Dublin, Galway and Wexford, and which lasted until the following Sunday, and of the trials and executions…The burning of the GPO and other buildings in O’Connell St., Dublin, and many other details were discussed by our companions and ourselves.

To Stack, his head spinning at these revelations, “the whole thing at the moment seemed to be one great tragedy.”

Failure and/or Success

More prisoners from Kerry and Limerick were added on board when the train paused at Mallow. Upon arrival in the capital – or what was left of it – they were marched en masse to Richmond Barracks, When locked in for the night, Stack and Collins found themselves in distinguished company, in the form of Arthur Griffith, Terence MacSwiney and Pierce McCann, and about thirty others, all crammed in a room meant for twelve, lacking blankets and with only the floorboards to sleep on.

Though conditions remained wretched and the rations no better, Stack was able to converse with MacSwiney, an old friend and the commander of the similarly ill-fated Cork attempt:

We compared notes as to the Insurrection which had taken place, and from the news which had begun to come to us from our visitors, we began to have hope that the people of the country had had the spirit of Nationality re-awakened in them.[30]

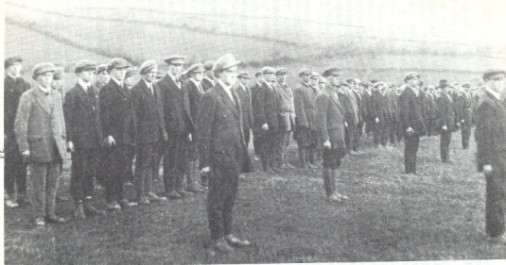

Such revived patriotism was on full display on the 31st August 1917, fifteen months after the Rising, at Caherciveen, where five hundred Kerry Volunteers assembled to welcome Stack, now a freed man, his life sentence having been revoked as part of the general amnesty. After a parade through the streets, the Volunteers drew up before a platform in the town square, from which a number of speakers, Stack among them, spoke to mark the forming of the local Sinn Féin Club, one of many which had been springing up all over Kerry and the rest of the country. The Caherciveen one alone could boast of two hundred members inducted on its opening day.

Stack had earlier attended, on the 28th July 1917, the Listowel Feis, as part of the promotion of the Irish tongue. After a lengthy address by Count Plunkett, whose son had been among those executed after the Rising, Stack next took the stage, appearing almost bashful before the crowd.

“Women and men of North Kerry, I can’t account for the fact that I am here today,” he began:

Or that I should be welcomed by you because, personally, I know I have done nothing to merit your kind reception. The little I had got to do in the matter of 1916 was, shall I say, somewhat of a failure.

This self-deprecation was met with cries of “It was a success!” When Stack continued, stating that he was no orator, nor intended to ever become one, a voice from the crowd suggested something better – “You’re a fighter!” – to general applause from an appreciative audience.[31]

Hard Facts

Regardless of what others said, Stack held no illusions as to whether the Rising in Kerry had been a success. Nor was he inclined to spare himself reproach. “I tried to keep it a one-man job,” he bemoaned in private, “and it was too much.”[32]

Stack had kept the plans so secret that his subordinates had been left floundering in his absence. His importance was singled out by County Inspector Hill, when testifying, on the 27th May 1916, to the Royal Commission, set up to investigate the disturbances of the month before:

Austin Stack was in charge of everything, and when he was arrested the Irish Volunteers who were assembled in Tralee became nervous. Those of them who were from the country districts gradually left for home.

This lack of coordination came under particular scrutiny by Sir Mackenzie Chalmers, one of the three members of the Commission, when he reviewed the checkmating of the Aud. Intercepted by British warships, the German vessel had been scuttled by its crew, who had then been taken into captivity.

Sir Mackenzie Chalmers: The German ship intended to land at Tralee?

Hill: Yes, by force.

Chalmers: There was not much preparation to receive it? Only two men in a motor car?

Hill: There was a large number in Tralee. My idea is that the ship came in a day or two too soon. She was unpunctual.

Another person of interest, Robert Monteith, was noted to be still at large.[33]

After the countermanding order had arrived at the Rink, Monteith decided that, since there was no further use for him with no Rising, the only thing he could do was run. The RIC were still on the lookout for the third man off the submarine, after all, and a strange face like his would be easy to pick out.

After the countermanding order had arrived at the Rink, Monteith decided that, since there was no further use for him with no Rising, the only thing he could do was run. The RIC were still on the lookout for the third man off the submarine, after all, and a strange face like his would be easy to pick out.

As a cover for his escape, it was arranged for him to leave after dark, amidst the Ballymacelligott Company while pretending to be just another local man. True to the secrecy that had characterised, and hamstrung, the Kerry Volunteers, only the Ballymacelligott captain and two others knew of Monteith’s identity.

These pair were put on either side of him as the company marched out of the Rink. A gas lamp lit up the area outside, allowing the police posted outside a good look at the departing Volunteers but the pace of the step, coupled with a downpour, allowed Monteith to escape undetected, hidden in plain sight.[34]

From there, Monteith fled, first to Limerick and then Liverpool, before finally reaching sanctuary in New York. He remained active in his country’s cause, via the Irish-American lobby, and later penned a memoir which captured the Rising-that-was-not in Kerry, in all its confusion.

“If there be readers who think I have been harsh, or unfair, or unduly severe,” he wrote in the preface, “I am sorry; but, I have to deal with men and hard facts.”[35]

References

[1] Reilly, Bernard (BMH / WS 349), pp. 2-6

[2] Casement, Roger (edited by Mitchell, Angus) One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement, 1914-1916 (Sallins, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2016), p. 41

[3] Ibid, p. 57

[4] Ibid, p. 232

[5] Ibid, p. 199

[6] Ibid, pp. 201, 221-2

[7] Ibid, p. 233

[8] Monteith, Robert. Casement’s Last Adventure (Chicago: Privately published, 1932), pp. 134-5

[9] Ibid, pp. 146-50

[10] Ibid, pp. 150-9

[11] Ibid, pp. 159-63

[12] Mullins, William (BMH / WS 123), p. 3

[13] Cotton, Alfred (BMH / WS 184), pp. 9-12

[14] Stack, Winifred (BMH / WS 214), p. 3

[15] Ibid, pp. 3-4

[16] Moriarty, Maurice (BMH / WS 117), pp. 2-4

[17] Stack, pp. 5-6

[18] Mullins, pp. 4-5

[19] Stack, p. 7

[20] Browne, Peter (BMH / WS 1110), pp. 4-5, 7-8

[21] Monteith, pp. 164-6

[22] Doyle, Michael (BMH / WS 1038), p. 6

[23] Monteith, pp. 166-7

[24] Ibid, pp. 171-2

[25] McEllistrim, Thomas (BMH / WS 275), p. 4

[26] Monteith, pp. 170-4

[27] Browne, pp. 8-9

[28] Irish Times, 11/05/1916

[29] Mullins, p. 4

[30] Stack, pp. 10-11

[31] Kerryman, 04/08/1917

[32] Lynch, Eamon (BMH / WS 17), p. 5

[33] Irish Times, 29/05/1916

[34] Monteith, pp. 175-6

[35] Ibid, p. xiv

Bibliography

Bureau of Military Statements

Browne, Peter, WS 1110

Cotton, Alfred, WS 184

Doyle, Michael, WS 1038

Lynch, Eamon, WS 17

McEllistrim, Thomas, WS 275

Moriarty, Maurice, WS 117

Mullins, William, WS 123

Reilly, Bernard, WS 349

Stack, Winifred, WS 214

Newspapers

Irish Times

Kerryman

Books

Casement, Roger (edited by Mitchell, Angus) One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement, 1914-1916 (Sallins, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2016)

Monteith, Robert. Casement’s Last Adventure (Chicago: Privately printed, 1932)