A continuation of: Plunkett’s Rising: Count Plunkett and His Family on the Road to Revolution, 1913-7 (Part I)

Failure to Comply

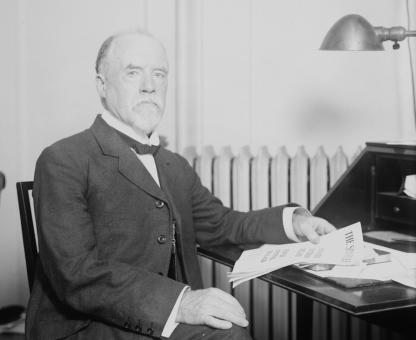

It did not seem like much, that small article on the fourth page in the Freeman’s Journal for the 15th January 1917, tucked away on the top right-hand corner as if the newspaper was faintly embarrassed by it. Under the headline ROYAL DUBLIN SOCIETY – COUNT PLUNKETT’S MEMBERSHIP, the Society announced its call on the member in question to consider his position:

It did not seem like much, that small article on the fourth page in the Freeman’s Journal for the 15th January 1917, tucked away on the top right-hand corner as if the newspaper was faintly embarrassed by it. Under the headline ROYAL DUBLIN SOCIETY – COUNT PLUNKETT’S MEMBERSHIP, the Society announced its call on the member in question to consider his position:

The Council of the Royal Dublin Society [RDS] intend a meeting to bring forward a resolution calling upon Count Plunkett to resign his membership of the Society. Under the statutes of the Society, if a member fails to comply with such a resolution within fourteen days he ceased to be a member of the society.

Having delivered the message, the Freeman was moved to comment in an editorial on the same page:

We hold no brief for Count Plunkett, but common justice urges us to point out that not only has he never been tried upon any charge, but that no charge has even been preferred against him.

In a moment of panic he was ordered by the Government to remove his residence to England – he was not even interned – but nothing that any fair-minded man could regard as a trial was afforded him. Yet the “non-political” Royal Dublin Society now proposes to pass their sentence upon him.[1]

The newspaper felt strongly enough to reprint the story the following day, accompanied by some strongly-worded letters from its readers. One compared the RDS to the brutish Lieutenant Hepenstall who had helped crush the 1798 Rebellion with wanton torture. Another sarcastically wondered if Plunkett had been accused of pickpocketing in the Society’s reading-room or perhaps of stealing an umbrella. Because otherwise: “It seems atrocious to thus blacken a man’s character, without even mentioning the crime of which he is accused.”[2]

Forced Resignation

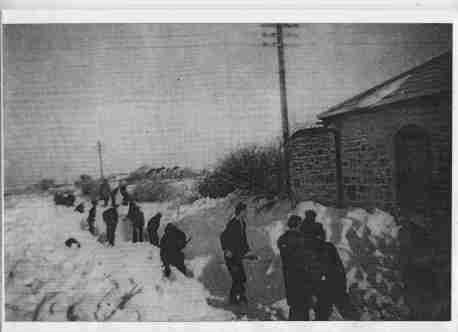

Nonetheless, the RDS pressed on remorselessly with its brand of rough justice. Three hundred of its members arrived at a meeting in Leinster House on the 18th January, making it the largest of its gatherings in many a year. The determination of many of the attendees was evident, as several aged and almost infirm gentlemen pressed on despite needing to be helped out of their motorcars amidst the snow and slush of a winter’s day.

Mindful of the sensitivity of its event, the RDS Council did not admit any representatives from the press. But if they had assumed the meeting would pass by without fuss or challenge, then they had misread the mood of its members, many of whom believed the Count to be the aggrieved party. The excitement of the meeting spilled outwards as messages were hurriedly dispatched to the Kildare Street Club and nearby hotels to find participants who had not yet turned up, as the RDS ‘whips’ began seeking the reinforcements they had not expected to need.

The session inside the Leinster House was to total two hours. The recommendation of the RDS Council, that Plunkett be called upon to resign, was countered with a proposed amendment that the matter be referred back for a further report as to the nature of the charges against the Count, complete with the necessary evidence. Which was the fault-line in the Council’s case – the lack of explanation as to what Plunkett had actually done to merit such blackballing.

All the Chairman of the Council offered was a reminder of how the Count had been arrested and deported to England as a danger to the Realm, in addition to being dismissed from his post as Director of the National Museum. But when the dissenters in the hall clamoured for something more substantial, the Council had nothing to add.

A Storm of Indignation

William Field, the Member of Parliament (MP) for Dublin St Patrick’s, was one of those who spoke up for the absent Count, whose friendship he had known for many years.

George Plunkett, he said, was a gentleman who would never stoop to an unworthy action. If there had been any clear connections between him and the recent insurrection in their city, surely he would have been imprisoned in Frongoch Camp along with the hundreds of others, many of whom had subsequently been released for the lack of evidence in their own cases.

Yes, the three sons of the Count had been involved, with the eldest one executed as a consequence and the other two sentenced to penal servitude. But, Field argued, why single out the father for the deeds of the younger generation?

Field finished on what would be a note more prescient than he could have guessed: he would leave the matter to public opinion, having no doubt that those supporting the amendment to save Plunkett from expulsion would be endorsed by the vast majority of Dublin citizens. It was emblematic of the role Count Plunkett would play later in the year – even without being present, he was a mascot for others’ sense of injustice and their need to respond.

Despite the vigorous defence mounted by Field and a handful of other stalwarts, the Council ended up having its way, and Plunkett was expelled by a vote of 236 to 58. At least the Count and his partisans could take solace in the sympathetic coverage by the Freeman, which guaranteed the story a wider audience than the internal complications of the RDS would normally enjoy.[3]

The Tipperary Board of Guardians, for one, was sufficiently moved to adopt a resolution condemning the “extremely bigoted action” of the RDS, predicting that a “storm of indignation” would occur, not only in Ireland, but throughout America and Australia as well.

As it turned out, while expecting those overseas to take much notice was a hope too far, the Guardians were not wrong in regards to the rest of the country.[4]

It was a sign of how drastically the Count’s circumstances would shift, and the mood of Ireland as a whole, that he and the RDS would be reconciled and he reinstated in 1921. “On that occasion,” to quote one historian, “the society displayed a shrewder sense of timing.”[5]

Unconventional

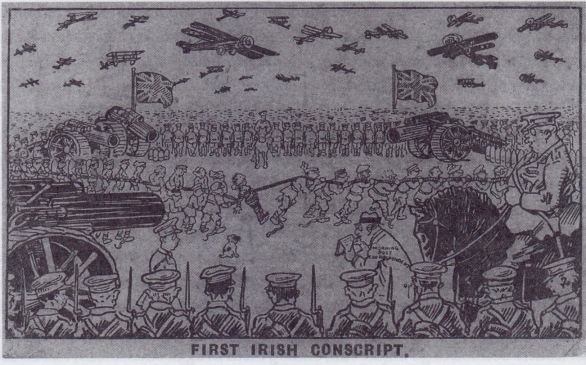

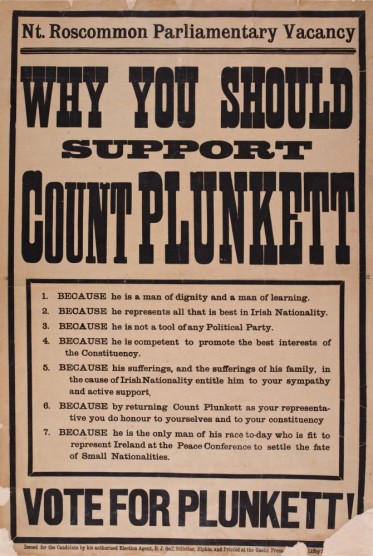

Meanwhile, plans were underway for an equally dramatic, though perhaps more important, contest in North Roscommon. Its long-time MP, James J. O’Kelly, had died in December after a lengthy illness. The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) was expected to replace its fallen member with another of its own, and made the first steps in this direction at its convention in Boyle, Co. Roscommon, on the 23rd January. Nominated there was Thomas J. Devine, a well-connected Roscommon native who had already served as a county councillor.

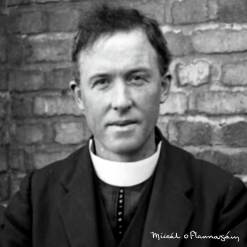

From the IPP’s point of view, Devine was a logical, if not terribly exciting, choice. The only hiccup at the event was the proposal by Father Michael O’Flanagan, the curate for nearby Crossna, that Count Plunkett be selected instead. When this was ruled out of order, the priest left the convention with a dozen other delegates.[6]

One has to wonder the course Irish history might have taken had the IPP agreed to field Plunkett after all, melding their constitutional approach with his connections to the Rising. After all, the Party could already claim its fair share of radicals in the past, such as the land agitator Michael Davitt and the late O’Kelly, a former Fenian.

But the IPP saw no need to try out novelties like running the elderly father of a rebel leader as one of its own. A generous observer might have concluded that the Irish Party was too intent on its hard-fought battle for Home Rule in the corridors of Westminster to be distracted. Critics would have dismissed it as hidebound.

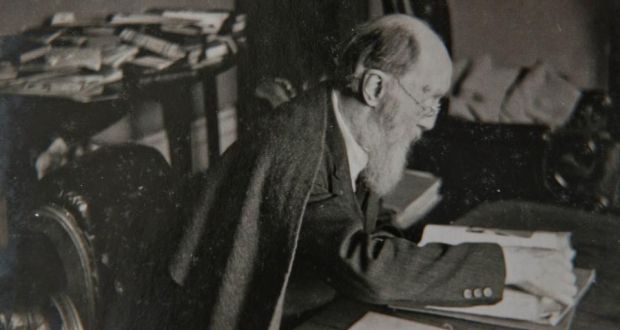

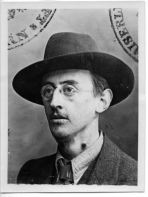

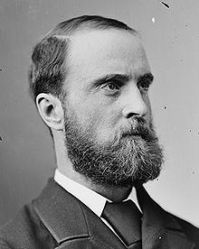

It was, admittedly, a peculiar attempt by Father O’Flanagan. As a Dublin-based art scholar and poet, Plunkett had not the slightest connection with Roscommon. He had dabbled in politics before in a series of brave attempts and doomed endeavours when he stood unsuccessfully for elections, once in Mid-Tyrone (during which he had been punched in the face by an angry mob) and twice in Dublin. He had stood by the side of Charles Stewart Parnell during the ‘Divorce Crisis’ of 1890, a minority stance which had required courage and a willingness to buck orthodoxy that even his friends were surprised by.[7]

But all that had been a long time ago. Yet O’Flanagan had come to the IPP convention with Plunkett in mind, having spoken in support of his man four days earlier at a meeting in Castlerea. What the curate saw in Plunkett, still in exile in England, was not obvious, and it was doubtful that the elderly intellectual would have crossed anyone’s mind if his ejection from the RDS had not been covered in-depth by the newspapers earlier that month. Which did not in itself seem to merit O’Flanagan’s praise of him as the only worthy candidate or the man who would best represent Ireland in the anticipated Peace Conference in Paris when the war in Europe was done.

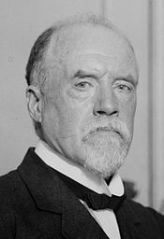

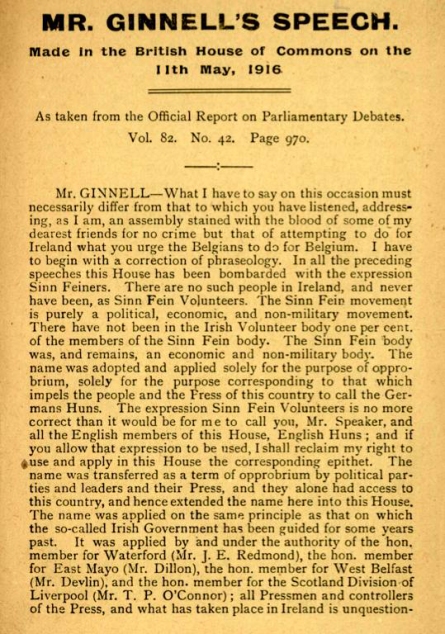

There had been no mention in Castlerea of any political parties or policies. Speaking alongside Father O’Flanagan was Laurence Ginnell, the MP for North Westmeath, but he was an Independent who had long been a renegade from mainstream Irish politics and his support did not indicate much in itself.

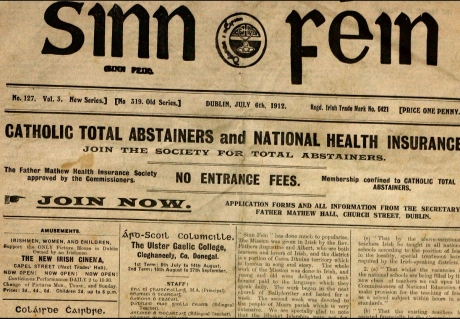

It was not until later that Plunkett was identified with Sinn Féin, where he was described as the party’s candidate by the Freeman in its edition for the 25th January. The candidate himself did not indicate any great desire to be associated with Sinn Féin, however. On his official nomination papers, submitted to the Boyle Courthouse on the 26th January on his behalf (he would not return to Ireland until the 31st), he was marked down as President of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language and Vice-President of the Royal Irish Academy – two worthy, if distinctly non-political, posts.[8]

Having previously defended the Count’s honour against the RDS, the Freeman was obliged to move against him as the struggle for the North Roscommon by-election intensified. He was, after all, standing against the candidate for the IPP, the party for which the newspaper served as a mouthpiece.

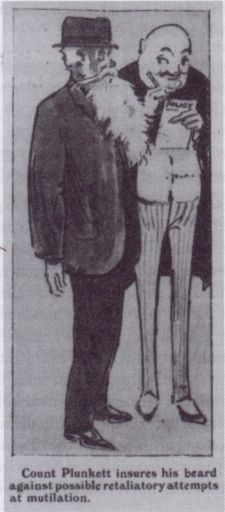

And so, under the headline COUNT PLUNKETT – WHAT IS HIS POLICY? – SOME PERTINENT QUESTIONS, the newspaper laid out a series of questions in regard to Count Plunkett:

- Was he a member of Sinn Féin or a supporter of its abstentionism policy? If elected, would he take the oath of allegiance to the British Crown as an MP?

- Did he approve of the recent Rising in Dublin?

- What policy did he propose to adopt in Westminster?

- Did he intend to reapply for his former position as Director of the National Museum?

“It will be very interesting,” purred the Freeman, “to learn from him on what platform he stands in the contest, for so far no light whatever has been afforded on to the public on this subject.”[9]

‘An Amiable Old Whig’

The Freeman was not alone in wanting to prise open a chink in the Plunkett armour. Jaspar Tully became the third candidate in what was now a three-way contest for the North Roscommon seat. A local businessman and the former MP for South Leitrim, Tully owned, among other things, the Roscommon Herald. Needless to say, the interview questions that the newspaper posed to its proprietor were distinctly tame, if not prearranged with the candidate.

Nonetheless, the points Tully thought necessary to raise or counter told a good deal about how the Count was perceived, albeit by a rival:

Interviewer: I imagined it was claimed last week that Count Plunkett was the candidate of the Sinn Feiners?

Tully: So it was said in surreptitious whispers at the opening of the contest, but we succeeded in getting to the root of the intrigue, and we discovered that the Dublin Sinn Feiners – or Irish Volunteers as they should be more properly called – had nothing to do with putting forward the Count as candidate. It was the work of this Seven Attorneys League from Tyrone, who are placeholders and seekers of posts under the Government.

Interviewer: What impression did the Count make on his audiences?

Tully: Oh, the very worst. The poor old man was unable to be heard a yard away from where he was speaking, and his mumbled platitudes were quite unintelligible to the people.

Interviewer: I thought he was to represent Ireland at the Peace Conference?

Tully: He could not represent Ireland at even a District Council meeting, as the members would so tire of him that they would not listen to him for half an hour. An amiable old Whig is a correct description of the Count. Then the fact that was brought to light that in the days in which he said he had a nodding acquaintance with Parnell and Davitt, he was touting the Tory Government for the post of Resident Magistrate throws a keen light on the class of man he is.

Interviewer: But then his son was shot by orders of Sir John Maxwell’s courtmartial?

Tully: Quite so; we all have the deepest reverence for the sacrifice he made, but I fail to see how the devotion of the son can change a Tory father into something he never was.

To illustrate his point, the candidate quoted a line that had been bandied about in Roscommon during the Land League days: ‘Many a good son reared a bad father.’

“As Count Plunkett’s party are trading altogether on this question of the poor boy that died,” Tully continued, referring to the executed Joseph Mary Plunkett, “it should be known widely that so did the father and son differ long before Easter Week that the son did not live with him and had to live in a place for himself.[10]

There was much more of a similar sort throughout the Herald in its lead up to polling day. As an Independent, Tully was also competing against the IPP runner. The fact that Tully focused the bulk of his personal jabs against Plunkett and not Devine made for a backhanded compliment, a salute to the danger that the “poor old man” was perceived to truly be.

Count Cypher

Much of Tully’s attacks could be dismissed as part of the electioneering game. After all, while Joseph did indeed leave the family house at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street, the rest of Plunketts, including his father, proceeded to move in with him on their property in Larkfield. As for the Count’s supposed inability to articulate, Tully and his pet newspaper had been the only ones to suggest such a thing.

(The journalist M. J. MacManus, who heard Count Plunkett speak at the by-election, remembered his “level, cultured tones.” While it was perhaps “the voice of a man who was more used to addressing the members of a learned society than to the rough-and-tumble of the hustings,” Plunkett seemed to manage his share of the public oratory well enough.[11])

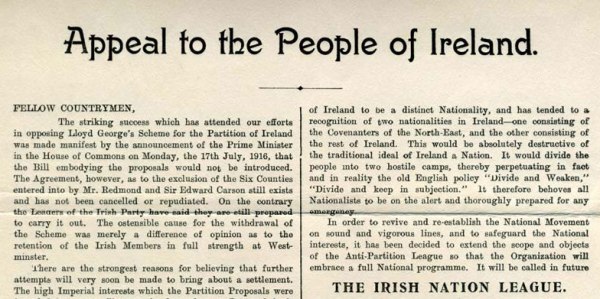

Yet both the Freeman and Tully had, in their different styles, touched upon a sensitive question for the Plunkett campaign: that of abstentionism. While Sinn Féin was canvassing for the Count in North Roscommon, so too were others, including the Irish Nation League – the ‘Seven Attorneys League’ mentioned by Tully – an anti-Partition group formed recently in Ulster. The former organisation opposed taking seats in Westminster, while the latter did not. So where, between them, did the Count stand?

As well as Plunkett’s commitments to Sinn Féin, it was also questioned how committed was Sinn Féin to him. According to Laurence Nugent, a worker during the campaign, the party not only refused to support the Count at first but did everything it could to stop him from standing.[12]

Another election activist, Kevin O’Shiel, told of a more nuanced reaction by Arthur Griffith, Sinn Féin’s founder. To any who asked, Griffith’s response was: “If Plunkett goes for Roscommon, all nationalists should support him.” In private, however, Griffith was distinctly cool towards a candidate he knew so little about.[13]

This uncertainty permeated the rest of Griffith’s organisation. Seamus Ua Caomhanaigh was an accountant on the Sinn Féin Executive when a man named Gallagher called in to see him in Dublin. Count Plunkett’s name had just appeared in the papers in connection with the by-election, and Gallagher, a native of Roscommon, wished to ensure that the candidate was “all right from the Sinn Féin point of view” before granting his support. Ua Caomhanaigh replied that, as far as he knew, the Count was indeed alright but first he would have to seek clarification from party headquarters.[14]

Others were quick to grasp the potential of the Count as political horseflesh. The trade unionist William O’Brien was talking with P.T. Keoghane, managing director of Gill Publishers, who he knew from the board of the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependants’ Funds. The conversation took place in early January, before Plunkett’s candidacy became common knowledge:

Keoghane: What do you think about fighting North Roscommon?

O’Brien: Well, there are enough obstacles.

Keoghane: What are they?

O’Brien: Well, in the first place, money. I don’t know anybody who has any.

Keoghane: Apart from money, what are the objections?

O’Brien: Well, you want a suitable candidate and you want a programme.

Keoghane: As regards a candidate, what would you say to Count Plunkett?

O’Brien: I think he would be excellent because he would not require any programme. All you need do is introduce him as the father of Joseph Plunkett, who was executed in Easter Week.

O’Brien had first met Count Plunkett inside Richmond Barracks following the collapse of the Rising. Both men had played supporting roles in the build-up to the insurrection and were subsequently detained (O’Brien was not released until August 1916). Despite their shared experience, O’Brien did not think of the Count as much of a Nationalist, which did not stop him from approving of the other man as a candidate.

His account of the conversation with Keoghane – perhaps written with the benefit of hindsight – neatly captured the central plank of the Plunkett campaign: who the candidate was being less important than what he represented in a post-1916 Ireland.[15]

This is Going to Cost Money

While others sought to make sense of what was happening, Nugent had proceeded from Dublin to North Roscommon. Besides Nugent’s own lack of experience, the challenges he found were formidable: there was barely any organisation on behalf of the Count, and what funds there were had been donated by friends of Father O’Flanagan to help cover the curate’s expenses.

Nugent had discussed the matter at length with Rory O’Connor, a close ally of Plunkett’s, but the only advice O’Connor could give was “Do what you think is right.” The few forlorn Plunkettites Nugent met in the local Sinn Féin circles knew all too well that they could not expect any assistance from the rest of their party. They had not even known that Nugent was coming.[16]

Meanwhile, having heard no more about North Roscommon, O’Brien assumed the election was going well. He was, in any case, busy with his work for the Dublin Trades Council, of which he was secretary. At one of its meetings, he was taken aside by the vice-president, Thomas Farren, and introduced to Kitty O’Doherty, wife of the Plunkettite director of elections. She broke the troubling news that the campaign was at the point of collapse. While they had plenty of helping hands from the Roscommon youth, none of them knew what they were supposed to be doing.

Stirred into action, O’Brien and Farren went straight to the Count’s house at Upper Fitzwilliam Street. When they saw him, he had no collar or tie on, and was in the process of undressing when his visitors came. O’Brien relayed what he had just been told, not that Plunkett seemed very interested.

(O’Brien was unaware, but the Count had only just returned from his English exile, having ignored his probation to stay in Oxford. Tiredness would explain his apparent apathy.)

Plunkett did, at least, ask what should be done. O’Brien suggested sending out to Roscommon a couple of experienced workers from Dublin. The Count seemed to perk up at this:

Plunkett: Do you think these men could be got?

O’Brien: I do not know for sure, but I think so. Do you authorise me to see them?

Plunkett: Yes, certainly.

At this point, Farren nudged O’Brien and made a point of asking if he had any money. The Count took the hint:

Plunkett: Well, who is going to pay for all this?

O’Brien: Count, this is going to cost money.

Plunkett: All I have is £5, you can have it.

O’Brien: Very well, I will take it.

O’Brien thought Plunkett had been anticipating the question, for he took out the aforementioned fiver from his pocket and handed it over. Having only just come back from banishment would also explain the Count’s shortage of ready cash.[17]

Blood from the Lips

For all the doubts and confusion, the nominations of the three candidates on the 26th January had made Plunkett’s standing at least official. Four days later, an appeal for motorcars to assist in the canvassing was issued from the Plunkett residence on Upper Fitzwilliam Street. The Count would not return home from England until the following day on the 31st, so the appeal was probably made by O’Connor, who was using the house for his own work in reorganising the Irish Volunteers.

The deep snow in North Roscommon made travelling a challenge but the summoned cars got there all the same, giving the Plunkettites a small fleet of vehicles to match the IPP’s own. The campaign was starting to take shape.

Nugent’s wife arrived on the 31st January, a day before the Count was due in North Roscommon. She relayed a message from O’Connor, giving her husband their candidate’s itinerary, as well as instructions to meet the Count at Dromod Station, in Co. Leitrim, just outside Roscommon.

When Nugent did so, he explained to Plunkett the progress of his campaign, stressing “upon him the certainty of victory. [Plunkett] was rather bewildered as it was not easy to believe these statements unless one saw it for themselves.”

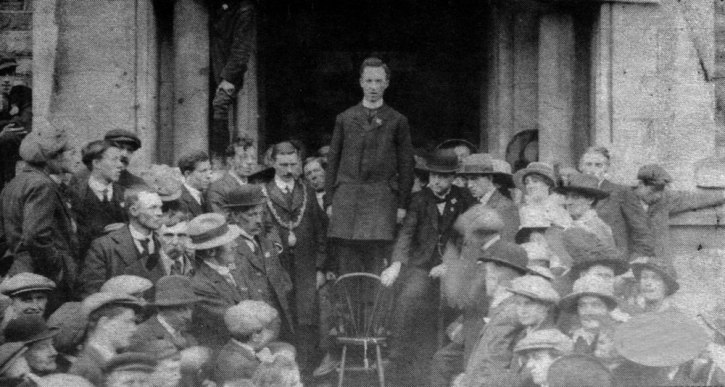

The Count was able to see it for himself when he continued to his last stop at Carrick-on-Shannon station, where he was greeted a huge crowd. These well-wishers formed a procession to accompany him across the bridge into Roscommon, where Father O’Flanagan was waiting.

Despite days of speaking in the icy cold, the priest remained unflinching, even when his lips broke and blood flowed freely down his jaw as he addressed the crowd. Count Plunkett spoke next in those level, cultured tones of his and, while he could not compete with a practised demagogue like O’Flanagan, he made, in Nugent’s estimate, “a great impression on his listeners.” By the time the rally was done, the previously befuddled candidate had been infused with a new sense of purpose.[18]

‘Up Roscommon!’

However much of an enigma the Count presented to friend and foe alike, that did not prevent the electorate of North Roscommon from voting him in by a landslide. Stationed at the polling booth in Rooskey, Nugent saw men vying with each other for the honour of being the first to cast a vote for Plunkett. They joked that as Roscommon had seen no action during Easter Week, they would make up for it by firing their ‘shot’ into the ballot box.[19]

Monsignor Michael J. Curran, secretary to the Archbishop of Dublin and a keen observer of Irish politics, recorded in his diary at the time:

Rarely has there been so much excitement over an election result. Count Plunkett started at the eleventh hour with little local backing…Though his supporters had hopes of his success, they never for a moment dreamed of such a resounding victory.

Up to Saturday, the Irish Party believed that they were winning. The news of the success astounded and delighted the ‘man in the street’…Count Plunkett’s success was entirely due to his own banishment, to the memory of his son, Joseph, and the imprisonment of two others.[20]

“Doubtless, too,” the Monsignor added wryly, “he was helped by his expulsion from the Royal Dublin Society.” Curran, like O’Brien, clearly did not attribute Plunkett’s victory to his own qualities. Perceptively, Curran also made note of how the issue of an Irish republic, as distinct from straightforward independence, was absent during the election.

“Doubtless, too,” the Monsignor added wryly, “he was helped by his expulsion from the Royal Dublin Society.” Curran, like O’Brien, clearly did not attribute Plunkett’s victory to his own qualities. Perceptively, Curran also made note of how the issue of an Irish republic, as distinct from straightforward independence, was absent during the election.

(This omission – or flexibility, depending on one’s perspective – would be cited by none other than Michael Collins, one of the many Young Turks who would cut their teeth working on the Plunkett campaign. A few years later, in the course of the Civil War, Collins was to argue that the example of North Roscommon proved how “absence of key principles was not incompatible with the strength of national feeling.”[21])

Count Plunkett returned to a hero’s welcome in Dublin on the 6th February, three days after his stunning victory. A large crowd had been waiting at Broadstone Station and cheered upon the arrival of his train, with hearty cries of “Up Roscommon!” and “Up the rebels!”

Upon disembarking, the Count was carried out of the station on the shoulders of his supporters to where a crowd – estimated by the Irish Times to be in the thousands – had assembled with much singing, cheering and shouting. Plunkett obliged the onlookers with a short address which was frequently applauded. When that was done, the people accompanied their hero as he was driven in a taxi-cab through the city centre, albeit slowly amongst the press of bodies, to his stop at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street.

Plunkett had only just entered the building when the apparently insatiable masses outside called for another speech. In response, the newly-minted MP appeared at a window on the first floor. As a tricolour was waved beside the Count in a suitably dramatic fashion, he indulged his adoring followers.

An Alternative Parliament for a Free People

He had come back, he told them, with a message for the city. A blow had been struck for Ireland and he would ask his fellow citizens, many of whom would recall his efforts to be elected for St Stephen’s Ward some twenty years ago – though it was questionable as to how many actually did remember an event two decades past – to ensure that their public representatives would no longer be beholden by the false need to wait upon an alien parliament in Westminster.

When he had travelled down to Roscommon, his chances of success had seemed very slim indeed. A local man there who owned a newspaper – Plunkett did not deign to name Tully who had so insulted him – had had it said that he, Count Plunkett, was a feeble old man with no work left to give for Ireland. As for the other losing candidate, a very respectable townsman of whom Plunkett would never say anything unkind, he had had behind him the full machinery of the Irish Party. What had been the result?

“You are in,” answered a voice from the crowd below to appreciative cheers.

Roscommon had arisen, the Count continued, and had swept his opponents away. Irishmen should see that in the future their leaders would be the soul of the nation. For that to happen, it was necessary to carry on with the work already begun until the whole of Ireland’s representatives were pledged to serve in Ireland and nowhere else; until, indeed, enough men were elected to form an alternative parliament for a free people. And at this, Plunkett finally withdrew into his house for some well-deserved rest.[22]

The Sinn Féin Candidate?

All this talk of abstaining from Westminster in favour of an Irish counter-parliament was straight out of the Sinn Féin playbook. Griffith had long expounded upon the need for such an assembly, one wholly divorced from any foreign system.

Plunkett was something of a late convert to this ideal. There is certainly nothing in his history to suggest he had been anything other than a conventional parliamentarian. His election director in Roscommon went as far as to interview him beforehand to ensure he was standing on an abstentionism platform but others in the Sinn Féin camp were not so convinced that Plunkett was one of them even while they campaigned on his behalf.[23]

Either way, the Count quickly made his mind known. In North Roscommon, he had announced in his acceptance speech that he would not be taking his seat in the House of Commons, causing “a mild form of consternation” amongst those who had only just voted for him and were not expecting their new MP to be quite so…different to the usual. Any doubts as to what he had said were cleared up when he arrived back to Dublin and spoke to the crowd outside his home.[24]

At no point did Plunkett acknowledge Griffith as the originator of the abstentionism policy. To hear the Count talk, one would have thought he had come up with the stance entirely on his own volition.

To be continued in: Plunkett’s Agenda: Count Plunkett against Friend and Foe, February-April 1917 (Part III)

References

[1] Freeman’s Journal, 15/01/1917

[2] Ibid, 16/01/1917

[3] Ibid, 19/01/1917

[4] Ibid, 22/01/1917

[5] Laffan, Michael. The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 79

[6] FJ, 23/01/1917

[7] Laffan, Moira. Count Plunkett and his Times (1992), p. 13 ; Tynan, Katharine, Twenty-Five Years: Reminisces (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1913), p. 383

[8] FJ, 27/01/1917

[9] Ibid, 01/02/1917

[10] Roscommon Herald, 03/02/2017

[11] Irish Press, 15/03/1948

[12] Nugent, Laurence (BMH / WS), p. 67

[13] O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770), Part V, pp. 28-9

[14] Ua Caomhanaigh, Seamus (BMH / WS 889), p. 116

[15] O’Brien, William, Forth the Banners go: Reminiscences of William O’Brien, as told to Edward MacLysaght (Dublin: The Three Candles Limited, 1969), pp. 124, 139-40

[16] Nugent, p. 70

[17] O’Brien, Forth the Banners go, p. 141

[18] Nugent, pp. 72-4

[19] Ibid, p. 76

[20] Curran, M. (BMH / WS 687), pp. 199-200

[21] Talbot, Hayden (preface by De Búrca, Éamonn) Michael Collins’ Own Story (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2012), p. 40

[22] Irish Times, 07/02/1917

[23] O’Doherty, Kitty (BMH / WS 355), p. 37 ; O’Kelly, Seán T. (BMH / WS 1765), p. 120

[24] Roscommon Herald, 10/02/1917

Bibliography

Books

Laffan, Michael. The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Laffan, Moira. Count Plunkett and his Times (1992)

O’Brien, William. Forth the Banners go: Reminiscences of William O’Brien, as told to Edward MacLysaght (Dublin: The Three Candles Limited, 1969)

Talbot, Hayden (preface by De Búrca, Éamonn) Michael Collins’ Own Story (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2012)

Tynan, Katharine. Twenty-Five Years: Reminisces (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1913)

Newspapers

Freeman’s Journal

Irish Press

Irish Times

Roscommon Herald

Bureau of Military History Statements

Curran, M., WS 687

Nugent, Laurence, WS 907

O’Doherty, Kitty, WS 355

O’Kelly, Seán T., WS 1765

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

Ua Caomhanaigh, Seamus, WS 889

Hayden closed his speech with an exhortation to “stand by the policy of Parnell and James O’Kelly, to stand by a united and disciplined Irish Party…and thus show that no policy of any sort or kind, whether it be Sinn Fein, Irish Nation League or Tullyism will be tolerated in opposition to a pledge-bound Irish Party.” Such language spoke much about the mindset of the IPP and how it still saw itself as the only viable option for the nationalist vote.

Hayden closed his speech with an exhortation to “stand by the policy of Parnell and James O’Kelly, to stand by a united and disciplined Irish Party…and thus show that no policy of any sort or kind, whether it be Sinn Fein, Irish Nation League or Tullyism will be tolerated in opposition to a pledge-bound Irish Party.” Such language spoke much about the mindset of the IPP and how it still saw itself as the only viable option for the nationalist vote.

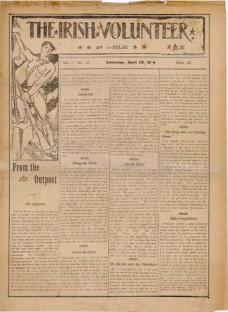

The role played by the Volunteers was another innovation, though there had been doubt that they would be involved at all. The trade unionist William O’Brien was discussing the state of the country with Arthur Griffith when the subject of the ongoing by-election came up. O’Brien remembered how a vacancy had occurred in the West Cork constituency, near the end of the previous year. The Volunteers there had opposed the running of a Republican candidate, resulting in a win by the IPP. In light of that example, O’Brien told Griffith that he doubted that the Volunteers would be any more accommodating in North Roscommon.

The role played by the Volunteers was another innovation, though there had been doubt that they would be involved at all. The trade unionist William O’Brien was discussing the state of the country with Arthur Griffith when the subject of the ongoing by-election came up. O’Brien remembered how a vacancy had occurred in the West Cork constituency, near the end of the previous year. The Volunteers there had opposed the running of a Republican candidate, resulting in a win by the IPP. In light of that example, O’Brien told Griffith that he doubted that the Volunteers would be any more accommodating in North Roscommon.