Journey in the Dark

The struggle had been a hard one but at last the three men, Colm Ó Lochlainn, Denis Daly and Sam Windrim, could claim a victory – something otherwise in short supply – when they reached the mountain pass of Bealach Óisín. This was despite the plaintive protests of their car, with its hissing, spluttering engine, which had forced the trio to get out and push the floundering vehicle over the last few yards. For a long while afterwards, all they could do was slump over the bonnet, utterly exhausted, but on the brink of escape from Co. Kerry.

As it was now dark, the three men slept as best they could, huddled together in the rear seat. Though they did not know it yet, Ó Lochlainn and Daly were all that remained of a five-strong team who had left Dublin the day before, on Good Friday 1916, as part of the opening moves in a national upheaval set to happen the following week at Easter.

Not that Ó Lochlainn knew much about it. Despite his place on the Irish Volunteers Executive, and his rank as captain on the staff of Joseph Plunkett, their Director of Intelligence, he had only been told the day before, Holy Thursday, when Plunkett briefed Ó Lochlainn about an operation he was to undertake in Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, involving a wireless station near there to be dismantled and removed elsewhere.

Even then, Ó Lochlainn was ignorant as to the whys, until another high-ranking figure in the Irish Volunteers, J.J. ‘Ginger’ O’Connell, stopped by later that Thursday at Ó Lochlainn’s house in Dublin, seeking to have some gaps in his own knowledge filled:

I told Ginger where I was going and he informed me he was off the following morning to take charge of the Volunteers of the Kilkenny and Carlow districts. He told me that a rising had been planned to start on Easter Sunday…but at that time he knew very little about what was going to take place, and wanted to know if I knew anything to confirm the rumours in circulation.[1]

Ó Lochlainn did not. Daly knew more, albeit only a little, from attending a series of strategy meetings with Seán Mac Diarmada, Michael Collins, Con Keating and Dan Sheehan:

As I understood it at the time, the main purpose of our mission was to enable wireless contact to be made with a German arms ship (I don’t think name of vessel was mentioned), which was expected at Fenlit on Easter Sunday.

The second objective was apparently to misdirect any Royal Navy warships off the South-West coast, via the wireless messages from the pilfered equipment, away from Tralee Bay where the German vessel in question would land. However “I cannot, from personal knowledge, confirm or deny, that there was such an intention,” Daly later wrote. “It is possible, but I do not recollect any discussion on the matter.”

Years might pass but much about the event that had changed Ireland irrevocably would remain obscured in ignorance, even to its participants.

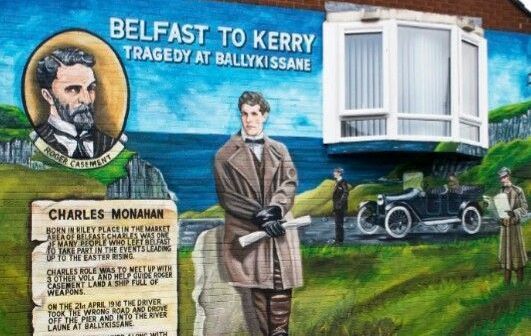

Daly guessed that if anyone in the team had the dummy codes to send, it would have been Keating, a Kerryman who was to be their wireless operator. He and Daly were selected for the group, along with Ó Lochlainn and Sheehan, who had previously lived in London, where he helped procure rifles to be smuggled over to Ireland. Another conspirator, Joseph O’Rourke, was intended to go as the fifth man but Mac Diarmada decided at the last minute to keep him in Dublin to help coordinate the upcoming revolt and sent Charles Monahan, a Belfast native, in his place.[2]

Who was in charge is uncertain, as both Ó Lochlainn and Daly claimed command in their respective accounts. The two men met for the first time on the Friday morning at the Ballast Office, Westmoreland Street, where they were introduced to each other by Michael Collins, who then handed them their train tickets for the journey.

Ó Lochlainn had come on a bicycle, which he left behind with Collins. When Ó Lochlainn later asked for its return, Collins told him that his bicycle had ended up in a barricade on Abbey Street during Easter Week.[3]

Entering the Kingdom

The team headed down to Killarney by train, with Ó Lochlainn and Daly in one carriage, and Keating, Sheehan and Monahan on another, in order to throw off suspicion. Code words for their arrival had been prepared in advance – “Are you John?” “Yes, William sent me” – but they seemed so obvious that it was agreed not to bother with them.

As it turned out, there were only two cars waiting at Killarney Station – a Maxwell and a Briscoe – and both with Limerick plates, which rendered any code words unnecessary. Keating got into one, while the other four men, for appearance’s sake, walked into town until reaching the College, at which point the cars picked them up.[4]

That is, at least, according to Ó Lochlainn’s version. In Daly’s, the group first had lunch in a pub in Killarney, before going to a road junction outside town at the appointed time:

The cars were there. Both cars were the property of Tommy McInerney of Limerick. He drove himself and the other was driven by a driver of whose name I do not remember. We had never met either man before.[5]

The second wheelman, Sam Windrim, had been drafted in at the last minute when domestic circumstances made it impossible for the intended driver, John Quilty, to participate. Both McInerney and Quilty were Limerick Volunteers but Windrim was a newcomer and so it was deemed necessary for the other two to first take him to the privacy of an upstairs office in Limerick and swear him to secrecy.[6]

Again, Ó Lochlainn and Daly stayed together in the Maxwell, the remaining three in the Briscoe. The former group were driven ahead by Windrim, with the others at their tail, staying close enough to see each other’s lights. “It was never intended that we should separate,” remembered Daly.[7]

Ó Lochlainn watched the hedgerows and stone walls of the Kerry landscape pass by, while the sky deepened into twilight and then night. He also kept a close eye on the Briscoe to the rear, though not closely enough, because, after three miles out of Killorglin town, he realised that he could no longer see the headlights. The other car was gone.

They doubled back to search, straining their eyes through the gloom, to no avail. They stopped and waited, hoping that it was just a case of engine trouble or a flat tyre, and that their comrades would reappear at any moment but, as an hour passed, that no longer seemed feasible. Deciding that their mission took precedence, Ó Lochlainn, Daly and Windrim pressed on to Cahersiveen, only to be stopped on the road by a whistle-blast from ahead.

Two figures stepped into the headlights, showing themselves to be a sergeant and a constable in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). Ó Lochlainn instinctively reached for the revolver he had borrowed from Plunkett.

Escape from Kerry

“Will we shoot?” asked Daly.

“No,” Ó Lochlainn replied. “I let someone else start the war. Talk will do for these fellows.”

Ó Lochlainn’s instincts proved correct. The three passengers explained that they were medical students to the RIC pair, who proceeded to give the car the briefest of searches. When they found a box and a bag, the explanation that the first held boots and the other clothes was enough to dissuade the policemen from peering inside.

In truth, the trio were equally ignorant of the contents, and it was only after the RIC men waved them through that they had a look for themselves. What they found was enough to startle Ó Lochlainn:

Oh! sergeant; that box contained two jemmies, a keyhole saw and a few other trinkets. The bag held an assorted collection of electrical appliances, two hatches and a heavy hammer.

Had the police been more thorough, the ‘medical students’ would have had a hard time explaining why their profession required these particular items. As it were:

Over the edge went the lot, owners having no further use for same. The job was off – a few words let drop by the sergeant had let out that a platoon of soldiers had come…and that all police units were on patrol.[8]

Ó Lochlainn and Daly agreed that the only thing to do was leave Kerry, since neither of them had the necessary technical knowledge to dismantle and rearrange the wireless set as intended. That responsibility would have lain with Keating and possibly Sheehan, and they were MIA with Monahan. Given the agitated state of the authorities, it was surmised that the second car had been stopped back in Killorglin and its occupants arrested.[9]

The only route out of the Kingdom ran through the narrow pass at Bealach Óisín, and to there they went, or at least tried to, for both the hilly terrain and their car fought them every inch of the way. For an hour they struggled uphill in the dark, much to the perturbation of their vehicle:

She was slipping and spitting and racing and faltering and stumbling and once she got one hind wheel into a gull and nearly turned over, and then we pushed and heaved and slipped and swore and called on the Lord and groaned and grunted until we arrived at last where the story begins.[10]

But, for them, it was the end. The car almost made it to Killarny, before breaking down for good. Ó Lochlainn and Daly left Windrim with his defeated Maxwell, and walked to the train station in time to catch the morning ride back to Dublin. While changing carriages at Mallow, Co. Cork, they received word that there had been arrests made in Kerry.[11]

Wrong Turn

But not of Keating, Sheehan or Monahan. Ó Lochlainn only learnt of their fate a month later when he chanced upon a newspaper article. It had been reported earlier, on the Easter Monday of the 24th April but, given the brief attention the story received in the Irish Times, a reader could be forgiven for overlooking it:[12]

THREE MEN DROWNED IN KERRY – MOTOR CAR JUMPS INTO A RIVER

Three men, whose names are unknown, were drowned in the River Laune, near Killorglin, Thursday night. They were motoring towards Tralee and, taking the wrong turn, the car went over the quay wall, and the three men were drowned. The chauffeur escaped. Two of the bodies were recovered last evening.[13]

That the newspaper incorrectly dated the incident to Thursday and not the Friday shows how little was known at the time. John Quilty, in whose car the drowned men had been, heard that McInerney, the driver and sole survivor, had lost his way and asked for directions from a young girl on the roadside.

“First turn on your right,” she said, the direction leading an oblivious McInerney, driving almost blindly in the dark, down a cul-de-sac to Ballykissane Pier, over which they plunged.

Sheehan and Monahan went down with the Briscoe, but, as McInerney later told Quilty, he and Keating managed to pull free and swam together in the cold waters, shouting for help until a light appeared to guide them to shore.

Keating never made it, suddenly disappearing beneath the surface with a cry of “Jesus, Mary and Joseph”. McInerney pressed on until he reached dry land, where he was assisted by Patrick Begley, a schoolteacher who, as luck would finally have it, possessed enough Fenian feeling to hide McInerney’s gun before the RIC could find it on him.[14]

Supplied with a policeman’s uniform in place of his wet clothes, McInerney fenced with the questions posed to him, insisting to the RIC that he knew nothing about the other men and had only been hired to drive them to Cahersiveen. When Windrim – after seeing Ó Lochlainn and Daly off out of Kerry – and Quilty, whose number plate was on the salvaged Briscoe, were picked up in turn by the authorities, they too kept schtum, insisting on only the most innocent of motives for all involved.[15]

Coming to a Halt

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the newspapers, a second report concerning a most unusual occurrence in Kerry was published by the Press Bureau on that same day of Easter Monday:

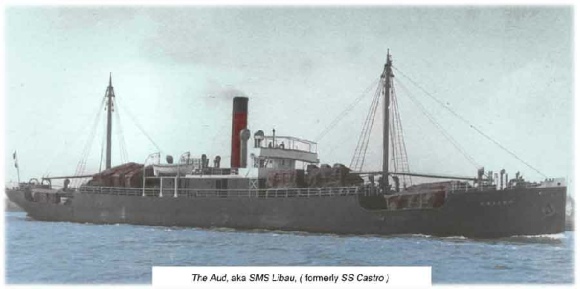

The Secretary of the Admiralty announces – During the period between p.m. April 20 and p.m. April 21 an attempt to land arms and ammunition in Ireland was made by a vessel under the guise of a neutral merchant ship, but in reality a German auxiliary…The auxiliary sank and a number of prisoners was made.[16]

It was but one mishap that slowly but surely unravelled the plans for the Rising.

Captain Jeremiah O’Connell had assembled ten Kerrymen from his Cahersiveen Company on Easter Sunday, the most he could find on short notice. As it was he who had dispatched Keating to Dublin to answer a request for a man trained as a wireless operator, he was more in the loop than most.

He had also been told to find a pilot for the boat that was to escort their German visitors to shore when they arrived, at which point O’Connell would lead his squad to Tralee by bicycle and capture the barracks, railway station and post office. The Cahersiveen Volunteers were on their way to do just that when, upon reaching Killorglin, they learnt of the tragedy at Ballykissane. The earthly remains of their fellow Kerryman, Keating, was already lying in the courthouse.

Continuing on to Tralee, they next discovered that things had gone from bad to worse: not only had the German vessel been captured but fresh orders from Eoin MacNeill, their Chief of Staff, had come through to call off the whole venture, with the would-be rebels ordered back to their homes. There was nothing left for O’Connell and his subordinates to do but just that.[17]

As it happened, even if the five men had succeeded in obtaining the wireless radios, the mission of the German ship – the Aud – could still have only ended in defeat. Messages transmitted to New York were to have been received by sympathetic Irish-Americans and then forwarded to the German embassy to ensure that the Aud appeared off the Kerry coast at the assigned time and with knowledge of the signals to give and receive from the shore.

For Want of a Nail…

Such an intervention from a friendly power could tip the odds decisively in favour of the Rising. When Patrick McCartan, whose role was to help facilitate these trans-Atlantic communications, met one of his co-conspirators, Tom Clarke, in Dublin, he found that:

Tom was enthusiastic about the prospect. He said there were at least 5,000 Germans coming and he was all enthusiastic about how thorough the Germans were and that they would do things in a big way, so that I left him for the first train next morning as enthusiastic as himself.

As it turned out, the rebels had severely overestimated their ‘gallant allies in Europe’. No one seemed to have realised that the Aud, already on course for Ireland:

…had no wireless. They acted on the assumption that the Germans were so thorough and perfect in all their arrangements that there would have been a means of communicating with the Aud.[18]

The result was that the ship arrived on the Thursday, the 20th April, three days earlier than the expected Sunday, with no one present to receive them with signals or pilot-boats. The crew waited in the waters of Tralee Bay for twenty hours before passing warships in the Royal Navy grew suspicious and intercepted the Aud as it tried to escape to the high seas.

Its cargo of 20,000 rifles fell short of the 5,000 soldiers Clarke had been anticipating but the loss was still sufficient enough for MacNeill – already skittish about their chances – to conclude that insurgency was no longer practical. With that decision came the cancellation orders that Jeremiah O’Connell and other Irish Volunteers all over the country received in time to stop them in their tracks on Easter Sunday.

Its cargo of 20,000 rifles fell short of the 5,000 soldiers Clarke had been anticipating but the loss was still sufficient enough for MacNeill – already skittish about their chances – to conclude that insurgency was no longer practical. With that decision came the cancellation orders that Jeremiah O’Connell and other Irish Volunteers all over the country received in time to stop them in their tracks on Easter Sunday.

Though the Rising would go ahead the next day regardless, it did so in a piecemeal manner, limited to the capital and a handful of other areas, and did not last the week.[19]

Small wonder, then, that when Frank Henderson, one of the participants-to-be in Easter Week, was reading the evening papers about the mishaps in Kerry, he had the sinking feeling “that we were going to have a repetition of all the previous insurrections.”[20]

Rarely had a wrong turn led to so many woes.

The Living and the Dead

There was a slightly eerie postscript to the episode. Alf Monahan had been in Galway during the Easter Rising, one of the few areas that did see action. When the rebels decided on the Saturday that further resistance was useless, Monahan accompanied Liam Mellows and Frank Hynes, the Galway commander and a company captain respectively, in going on the run, through the Galway wilderness and into Clare, where they were sheltered by the local Volunteers in a tiny, hillside cottage.

When provided with newspapers, the trio were able to catch up with events, from the heavy fighting in Dublin to the executions afterwards, including the drowning in Kerry. As only two names – Keating and Sheehan – were given, Alf Monahn did not know at first that the third victim was his brother, Charles.[21]

They stayed in the cottage until Mellows left for America on the orders of the new revolutionary leadership, after which Hynes was taken to Tipperary. When Monahan’s turn came near Christmas, he believed that the car that drove him away to safety was the same vehicle in which his brother had drowned eight months ago, with even the same chauffeur at the wheel, Tommy McInerney.

In this, Alf was mistaken, for it was the Maxwell car he was in, while Charles had taken his last ride that fateful night in the Briscoe. All the same, it must have made for an uncomfortable journey.[22]

See also: Dysfunction Junction: The Rising That Wasn’t in Co. Kerry, April 1916

References

[1] Ó Lochlainn, Colm (BMH / WS 751), pp. 2-3

[2] Daly, Denis (BMH / WS 110), p. 3 ; Furlong, Joseph (BMH / WS 335) p. 4 ; O’Rourke, Joseph (BMH / WS 1244), pp. 9-10

[3] Ó Lochlainn, p. 3

[4] Ó Lochlainn, pp. 3-4

[5] Daly, p. 3

[6] Quilty, John J. (BMH / WS 516), pp. 4-5

[7] Daly, p. 3

[8] Ó Lochlainn, pp. 4-5

[9] Daly, p. 4

[10] Ó Lochlainn, pp. 5-6

[11] Daly, p. 4

[12] Ó Lochlainn, p.6

[13] Irish Times, 24/04/1916

[14] Quilty, pp. 6-7 ; Cregan, Mairin (BMH / WS 416), p. 6

[15] Quilty, pp. 8, 10-2

[16] Irish Times, 29/04/1916

[17] O’Connell, Jeremiah (BMH / WS 998), pp. 3-5

[18] McCartan, Patrick (BMH / WS 766), p. 48

[19] Henderson, Ruaidhri (BMH / WS 1686), p. 6

[20] Henderson, Frank (BMH / WS 249), pp. 27-8

[21] Monahan, Alf (BMH / WS 298), pp. 38-40

[22] Ibid, p. 45

Bibliography

Bureau of Military Statements

Cregan, Mairin, WS 416

Daly, Denis, WS 110

Furlong, Joseph, WS 335

Henderson, Frank, WS 249

Henderson, Ruaidhri, WS 1686

Quilty, John J., WS 516

McCartan, Patrick, WS 766

Monahan, Alf, WS 298

O’Connell, Jeremiah, WS 998

Ó Lochlainn, Colm, WS 751

O’Rourke, Joseph, WS 1244