Another Day in Ireland

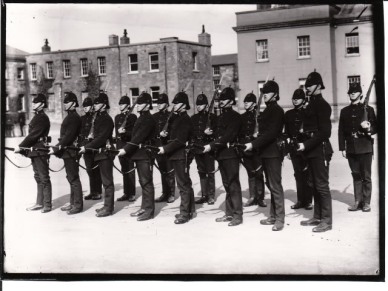

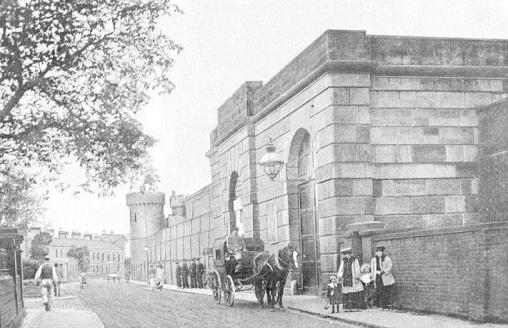

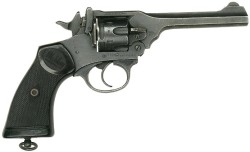

While it was still dark on the morning of 18th October 1920, a patrol of British soldiers helped themselves to a motorboat in Athlone for use on the Shannon, their aim being to scout out some small islands upriver in Lough Ree. That they felt the need to bring along a Lewis machine gun would indicate a sense of wariness.

After all, the area had been increasingly unsettled over the course of the year, with a number of police barracks burnt to the ground and a police sergeant shot dead on the streets of Athlone. But then, these barracks had already been abandoned and the sergeant was caught while leaving a social club with barely any company to protect him. At twelve-strong and fully armed, the patrol would present a very different prospect.

After finding nothing of note, the patrol began to make its way back around midday. As the boat passed through the narrows of the river, it was subjected to a broadside of bullets. Caught off-guard, the patrol stopped the motor and returned fire at the treeline along the shore where the attack was coming from. The Lewis was brought out to add to the fusillade but poor positioning – the boat was low in the water and the enemy standing on the high ground of the riverbanks – meant that its volleys went over the heads of its targets.

Upping the Ante

Exposed as they were and taking hits, the patrol had no choice but to restart their boat and withdraw as best they could. The ambushers followed along the bank, moving from cover to cover and keeping up their fire with a mix of shotguns and rifles. It was only when the boat neared Athlone with its still-functioning barracks there that the assailants broke off their attack and dispersed. The patrol limped back to safety with six wounded.

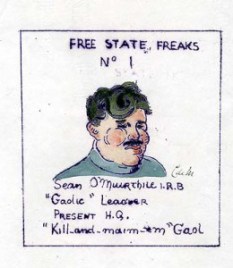

The attack had been an ad hoc affair by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The O/C of the Athlone Brigade, Seumas O’Meara, was in town to attend Mass when he heard about the soldiers who had left on a boat earlier that day. Recognising an opportunity, O’Meara gathered all the available Volunteers in Athlone and the Coosan area, near where the patrol had gone.

He had considered stringing barbed wire across the river but decided that the party lacked both a boat and the time necessary to attempt this. Hoping for as many casualties as possible, O’Meara told the others to aim for the waterline of the enemy launch before targeting the sinking men.

Despite the injuries inflicted, the Shannon ambush was not considered an unqualified success. O’Meara regretted the order to aim for the boat, believing it had wasted time that could have been spent on the soldiers. Another participant, Frank O’Connor, was of like mind, adding later in his Bureau of Military History (BMH) Statement that he had thought O’Meara’s instructions absurd, though it seems he had neglected to actually mention it at the time.[1]

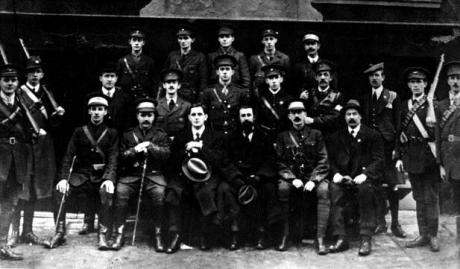

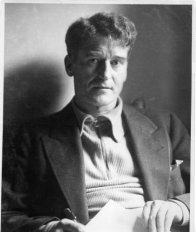

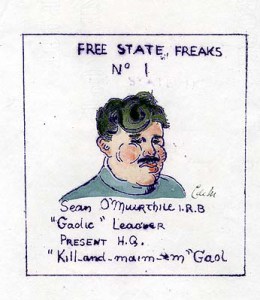

Seumas O’Meara

O’Meara’s leadership would remain a contentious issue. While undoubtedly brave, energetic and capable of creative thinking (as his idea with the barbed wire had shown), he had already exhibited a knack at rubbing his colleagues up the wrong way.

In early 1918, O’Meara was standing in as acting O/C of the Athlone Brigade while the official one was imprisoned when he was called upon to reprimand a pair of officers who had taken it upon themselves to arrange an unauthorised raid upon a quarry for gelignite. Other than the lack of discipline, the operation had involved rowing across a lake in bad weather, putting the lives of all involved at risk.

O’Meara made it clear that any future actions would have to be cleared beforehand by the Brigade staff. Smarting from the rebuke, the two malcontents took their complaints to the official O/C, Seán Hurley, upon his release from prison.

The first O’Meara knew of the problem was when Hurley addressed the Athlone Volunteers on parade. Without mentioning any name, Hurley made it clear that he held his acting O/C in the wrong. Feeling he had no choice, O’Meara tendered his resignation. But when the subsequent brigade staff meeting decided in favour of O’Meara, it was Hurley who resigned, leaving O’Meara to become O/C in time.[2]

It would not, however, be the last time that the discipline that O’Meara so highly valued would be come under threat.

At War and on the Run

The Shannon ambush heralded a rise in activity by the Athlone Brigade in the latter half of 1920. As part of this, a flying column was created to help spearhead this surge. Though the column would not take the field until after the Shannon ambush, plans for it had been underway for some time, encouraged in no small part by the increasing number of Volunteers having to go on the run.

A series of round-ups by Crown forces were disrupting the equilibrium of the Brigade areas. The wanted men who escaped arrest were threatening to be a burden on the Brigade – O’Meara had to hold a collection to raise funds for them – until a GHQ missive in September, ordering columns to be formed in all brigade areas throughout the country, turned these loose men into resources. The runaways made perfect recruits for the column, having little else to do. Included were those Volunteers willing to be absent from their home for the foreseeable future.

The first meeting of the embryonic column was held at O’Meara’s house in October where the personnel were selected. The initial numbers are uncertain, one source having the column at twenty, but others coming to more conservative estimations of between nine and twelve.[3]

All the rifles and the best shotguns were scoured from the Brigade units to equip the new one, something that was not greeted with wild enthusiasm by those outside the column. The Drumraney Company was sufficiently aggrieved to send their O/C to Dublin. There he prevailed upon GHQ to order the Brigade to return the Company armaments although only four rifles ended up being given back.[4]

Henry O’Brien – one of the column’s original members and later a stern critic – went as far as to argue that the donations of serviceable weapons to the column was crippling to the other units, which is something of an overstatement. After all, Athlone Volunteers outside the column were able to attempt a number of ambushes, successfully or otherwise, up until the Truce. However annoying this tithe of weapons might have been, it could not have been too much of one.[5]

Too Many Chiefs and Not Enough Indians?

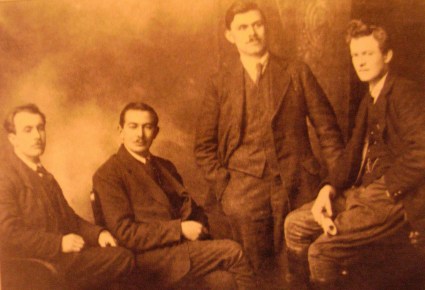

Also chosen was the O/C for the column. James Tormey was to be in command, a role for which he was ideally suited. In addition to having a “fine physique and of a commanding disposition”, he was one of the few Volunteers with prior military experience, having served with the British Army in France and at Gallipoli.

He had proven his mettle to his new comrades in the IRA: attempting to infiltrate the Streamstown RIC Barracks while disguised as a policeman (where he had narrowly avoided being shot) in July 1920, and acting as one of the shooters in the assassination of Sergeant Craddock in Athlone a month later.[6]

O’Meara served in the column as an ordinary soldier despite his position of Brigade O/C. Several others who held similar Brigade ranks likewise counted as regular Volunteers in the column while retaining the right to absent themselves and attend to their brigade duties when necessary. This dual membership policy would allow for the smooth running of the various IRA companies but it could create its own problems.[7]

O’Brien believed that being allowed to continue as officers made a lot of column members difficult to handle. A tendency for some to disappear without prior warning made unit cohesion a struggle to maintain and, being big fish in their own ponds, they were not as amenable to discipline as an ordinary Volunteer might be.

O’Brien was also sceptical about the endurance of many of his peers when faced with the hardships that life in the column would entail, such as long periods of hunger and poor billeting. As Captain of the Coosan Company as well as a column serviceman, O’Brien could claim to view the situation from both perspectives; nonetheless, that was the situation the column had set for itself. There was nothing else to do but press on and do what the column had been formed to do.[8]

Opening Moves

The first intended operation was a surprise on a military party on its way to relieve the guards at the Athlone Workhouse. A date was set for a Monday but then the Shannon incident happened on the Sunday, heightening British security and causing the cancellation of the original plan.

Needing to stay mobile, the column assembled at Faheran on the following Tuesday and Wednesday nights, billeting in a shed owned by an obliging parish priest. Looking for another angle, Tormey, O’Meara and David Daly ventured out on the Thursday or Friday and scoped the Dublin-Athlone road as a possible ambush site before deciding on Parkwood as having the best position.

The armoury was reviewed in preparation. Upon testing, the GHQ-supplied explosives were found to be duds. Daly was sent to Dublin to replace them. Though he successfully handed in the faulty explosives he received no replacements, not that he would have made it back in time anyway for what was to be the column’s christening.[9]

Parkwood

The column’s ambition was modest: a single lorry, two at most. As British forces routinely used the road, it would only be a matter of time and patience before suitable prey came within range if the column waited long enough in position.

The column took up position close to the road, putting the men at virtually point-blank range as a concession to the inexperience of many of them, with the exception of a few ex-British soldiers like Tormey, at handling rifles. The bulk of the group was concentrated on one side of the road with the remainder positioned on the other to counteract any enemies seeking refuge there.

The position gave the column a clear view of the road towards Athlone. As for the Dublin side, a scout took watch with a whistle and instructions to use it upon sight of a convoy. Blocking the road was ruled out due to the amount of traffic and the lack of a mine. It was not ideal terrain as cover was scarce but, committed as they were, the column settled down as best they could behind roadside fences and waited.

When opportunity came at about 1 pm after two hours of anticipation, on 22nd October, the column almost missed it. A military tender speeded by from the Dublin direction before the ambushers were aware of it. The scout blew his whistle in time for a second tender to appear before the poised men.

The column opened fire, aiming as ordered on the lorry driver and killing 26-year old Constable Harold Briggs instantly at the wheel. The tender careered off the road and into a ditch in front of the ambushers, just as several other vehicles appeared, coming to a halt by the rear of the disabled one. Their occupants spilled out, the Black-and-Tans firing mostly in the air as they dashed for the nearest cover. Instead of the lone or double tenders the column had been expecting, they had chanced upon a whole squadron.

He Who Runs Away…

Fearing they had bitten off more than they could chew, Tormey ordered a retreat. The column moved safely away until they reached another road where they commandeered a civilian lorry. The locals they passed working on the land either cheered as the lorry passed or turned their backs, the latter O’Meara attributed to the farmers thinking they were Tans.

The column dismounted and sheltered in the woods. While the men waited for the cover of night, O’Meara went ahead to make arrangements for transport across the Shannon, all the better to throw any pursuers off the scent.

In what could have been a disaster, the column had pulled off its first ambush. With one enemy fatality, another injury and no casualties of their own, it had been a success. The reaction of the Tans, in contrast, had been so confused and their discipline so abyssal that many of the column believed that had they stayed to fight, they could have wiped the convoy out entirely like ducks in a row.

On the other hand, these same Volunteers were honest enough to admit the precariousness of the situation. If the Tans had kept their nerve or had adequate leadership, they might have inflicted grievous losses on their assailants. [10]

In the Wilderness

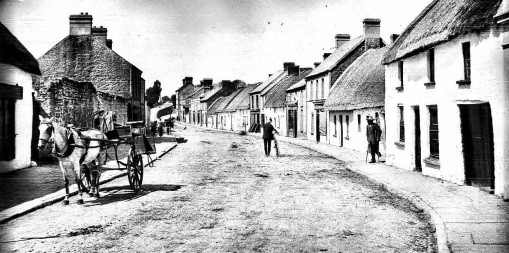

The column stayed in the Summerhill area for over a fortnight where Tormey utilised his British Army expertise to put it through a training course. Emboldened by their earlier success and not wanting to rest on their laurels, the Volunteers set up three ambush positions in succession for RIC cycle patrols, only for none to show. Skirting Athlone on its Connaught side, the column packed up and crossed the Shannon, aiming to set up camp near Ballymahon.

The column stayed in the Summerhill area for over a fortnight where Tormey utilised his British Army expertise to put it through a training course. Emboldened by their earlier success and not wanting to rest on their laurels, the Volunteers set up three ambush positions in succession for RIC cycle patrols, only for none to show. Skirting Athlone on its Connaught side, the column packed up and crossed the Shannon, aiming to set up camp near Ballymahon.

En route, the column held a court-martial of a prisoner held by the local Volunteers acting as a makeshift police force. The prisoner was found innocent and, though O’Meara does not give any further details, it is a reminder that the role of the IRA at this time was not limited to the military sphere.

Having arrived in Ballyhamon, the column slept in a hayshed for three or four nights. O’Meara searched for a suitable ambush site on the Athlone-Ballymahon road but when that proved fruitless, the column returned the way it had come, crossing the Shannon, and tried their luck again for a few more days along the Galway road but, once again, no enemy patrol was obliging enough to show itself.

Undaunted, Tormey decided to lead his unit to Faheran, where it had originally begun, and from there to Moate. If the column could not find any enemy patrols to attack there, it would try its luck against the local police barracks, though more for the nuisance value than any realistic hope of capturing it. [11]

Complications

It was at Moate that cracks appeared in the column. The men arrived at 3 am, near the ‘Cat and Bag’ publichouse, and were detailed to neighbouring billets with local Volunteers. O’Meara, who was shouldering some of the leadership duties in the column, told the men before dismissal to assemble outside the ‘Cat and Bag’ later in the day at 7 pm.

O’Meara and O’Brien, who had been billeted together, arrived at the publichouse at the appointed time to find only one other Volunteer there. After waiting for three hours in vain for the rest to show, the trio decided to have some tea inside.

The barmaid served them their tea but with bad grace and a refusal to take payment. Puzzled by the hostility, the three men resumed the wait outside until 11 pm when Tormey and another column member, Thomas Costello, arrived to say that the ‘Cat and Bag’ had been raided the previous night for drink and cigarettes. Worse, the culprits had been members of the column and the local Volunteers.

The discipline that the column depended on was in danger of coming undone. Tormey and O’Meara agreed that reigning in the baser instincts of their colleagues would be impossible and that it would be better to split up the column for better control.

That is at least O’Meara’s version of events. The other two present who left BMH Statements for posterity, Costello and O’Brien, agree that the column was divided around this time but no such incident at the ‘Cat and Bag’ is mentioned. But then it was not something on the column’s record that anyone would find flattering. That O’Meara described it all the same gives his Statement credibility. [12]

Whatever the reason, the column was never the same after Parkwood. While the column made an effort to follow through on its initial success, it would cease to function as a whole. Volunteers outside the column saw only a lull of activity and cited disorganisation and disarray as the cause.

Upon his return from Dublin, Daly found that many of the original members were absent. In their place were newcomers who had only the credentials of being on the run but not weapons of their own in a unit already lacking in armaments. “It was more of a gathering now than a column,” Daly thought. By Christmas the unit had disbanded for the holidays with the intention of reforming in the New Year. Perhaps they would have better luck by then. [13]

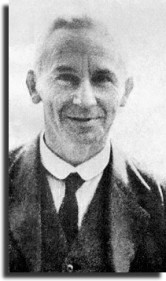

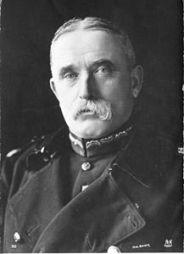

James Tormey

On 2nd February 1921, a party of eight RIC policemen on cycles were making their way up the Athlone-Ballinasloe road when they were fired upon. At the forefront of the assault was Tormey, grieving for his brother who had recently been shot dead by a sentry while in Ballykinlar internment camp. Impatience for revenge, Tormey had been leading an IRA party to Summerhill when he had spotted the forerunners of the RIC patrol coming towards them.

Accounts vary as to Tormey’s actions. One version has it that, much like the Parkwood ambush, Tormey assumed the few men ahead of him were alone and he failed to see the rest of their patrol, prompting him to shoot at what he falsely assumed would be easy targets.

In another retelling, Tormey could see the patrol in its entirety and, judging it to be too dangerous, ordered the others to hide. As the enemy passed by, Tormey, for whatever reason, broke his own instructions and his cover.

Alternatively, the ambush had been planned all along. That none of the sources – O’Meara, Daly and Thomas Costello – were present, and since Tormey never got a chance to explain, means that we will never know for sure.

A shootout ensured, with the two groups committed to a fight that perhaps neither had wanted. One of the Volunteers shot the cap off a RIC officer and promptly lost the foresights of his rifle to a return bullet – both men were otherwise miraculously untouched.

Belatedly deciding that discretion was the better part of valour, Tormey initiated a retreat, being the first into a ditch behind the ambush site. There he was shot in the head before he could realise he had been outflanked. Some of the RIC had edged down a lane that ran at right angles to the site, an opening the IRA had neglected to watch, from where they opened fire to surprise their ambushers in turn.

Belatedly deciding that discretion was the better part of valour, Tormey initiated a retreat, being the first into a ditch behind the ambush site. There he was shot in the head before he could realise he had been outflanked. Some of the RIC had edged down a lane that ran at right angles to the site, an opening the IRA had neglected to watch, from where they opened fire to surprise their ambushers in turn.

By the time the local Volunteers arrived and armed to assist, the ambushers and the RIC had left. Only Tormey’s dead body remained. Neither side had lingered long enough to take it. He was 21 years old. [14]

Leadership

Tormey’s death left a void that the remainder of the column worked hard, though never entirely succeeded, in filling. O’Meara took charge of the unit in addition to being Brigade O/C. According to Daly, however, he was not capable of shouldering the responsibility.

For his part, O’Meara felt undermined by the unraveling discipline within the Brigade as a whole. Individual officers and even ordinary Volunteers were taking it upon themselves to act without waiting for permission. Further undermining O’Meara’s authority was the suspicion that he was blocking any operations in Athlone for fear of his property or himself being harmed by the authorities in retaliation.

A solution came in late March or early April 1921 when a representative from GHQ, Simon Donnelly, arrived in the area. O’Meara had already submitted a report to Dublin asking for a suitable newcomer to be sent to replace him as O/C. Feeling that a fresh start for the Brigade was needed, O’Meara announced his intention to resign at a staff meeting with Donnelly.

According to O’Meara, Donnelly urged him to continue on, loath as he was to lose an experienced hand, but O’Meara insisted, arguing that given the doubts about him, it was impossible to continue. O’Meara got his wish and resumed service as an ordinary member in a column whose future was looking uncertain.

Despite O’Meara continuing on as an active Volunteer, there is a dearth of much further activity in his BMH Statement. When the Truce came into effect, he attended an IRA officers’ training camp where he was faced with the choice of taking up soldiering on a professional basis in an army that was to be restructured on regular lines or to return to the business he had neglected. O’Meara decided on the latter. Reading between the lines of O’Meara’s Statement, one can detect an air of exhaustion after all the work he had done and for very little reward or gratitude.

Despite O’Meara continuing on as an active Volunteer, there is a dearth of much further activity in his BMH Statement. When the Truce came into effect, he attended an IRA officers’ training camp where he was faced with the choice of taking up soldiering on a professional basis in an army that was to be restructured on regular lines or to return to the business he had neglected. O’Meara decided on the latter. Reading between the lines of O’Meara’s Statement, one can detect an air of exhaustion after all the work he had done and for very little reward or gratitude.

After the change in leadership, the column members were divided as O’Meara and Tormey had planned and now assigned to different areas. From there they would assist other Volunteers in their local battalions. The emphasis had shifted from a professional outfit to more part-time groups that would only assemble when needed and, hopefully, be easier to manage. The days of flying freely were over even if the War was not.[15]

Legacy

The Athlone column remained scattered up to the Truce, partly because of the new policy but also due to the increased pressure from the Crown garrison. The column, in the opinion of Henry O’Brien, had not been the success many had hoped. Poor luck and the elusiveness of the enemy had hampered ambushes being attempted, and the Brigade had been unable to seize large enough caches of weapons to augment its ever-limited armoury.

O’Brien believed that forming the column had been a mistake. Far better, he thought, to have gone with what eventually happened – smaller units formed and attached to battalion areas – from the start.[16]

The column left a mixed legacy – of missed opportunities and misplaced priorities, according to some. Nonetheless, it was able to pull off an ambush, no small feat in a war in which the vast majority of such attempts were thwarted in some way. Afterwards it had avoided capture or elimination, not something every column in the War could claim.

While far from a success, the Athlone flying column was at least not a failure. That may not be a particularly heroic legacy. But, then, heroics only go so far.

See also: Sieges and Shootings: The Westmeath War against the RIC, 1920

References

[1] O’Meara, Seumas (BHM / WS 1504), pp. 32-3 ; O’Connor, Frank (BHM / WS 1309), p. 18 ; Westmeath Independent, 23/10/1920

[2] O’Meara, pp. 10-12

[3] Ibid, p. 34 ; O’Connor, p. 24 ; O’Brien, Henry (BHM / WS 1308), pp. 11-2 ; Daly, David (BHM / WS 1337), pp. 16-8 ; Costello, Thomas (BMH / WS 1296), pp. 15-6 ; McCormack, Michael (BMH / WS 1503), p. 17 ; McCormack, Anthony (BMH / WS 1500), p. 9

[4] McCormack, Michael, p. 18

[5] O’Brien, pp. 22-3

[6] O’Brien, p. 11 ; Costello, p. 12 ; O’Meara, p. 31 ; Westmeath Examiner, 12/02/1921

[7] O’Brien, p. 11 ; Costello, p. 16 ; O’Meara, p. 34 ; Daly, p. 17

[8] O’Brien, p. 22

[9] O’Meara, pp. 34-5 ; Daly, pp. 17-8

[10] O’Meara, pp. 35-7 ; O’Brien, pp. 12-3 ; Costello, pp. 16-7 ; McCormack, Anthony, p. 10 ; McCormack, Michael, p. 17 ; WI, 30/10/1920

[11] O’Meara, pp. 37-8 ; Costello, p. 17

[12] O’Meara, p. 38

[13] McCormack, Anthony, p. 10 ; McCormack, Michael, p. 18 ; Costello, p. 17 ; Daly, pp. 21, 23

[14] O’Meara, pp. 45-7 ; Daly, pp. 22-3 ; Costello, p. 18 ; WE, 12/02/1921

[15] Daly, p. 22 ; O’Brien, p. 24 ; O’Meara, pp. 47-8, 50 ; O’Connor, p. 23 ; McCormack, Anthony, p. 10

[16] O’Brien, pp. 22-3

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History / Witness Statement

Daly, David, WS 1337

McCormack, Anthony, WS 1500

McCormack, Michael, WS 1503

O’Connor, Frank, WS 1309

O’Brien, Henry, WS 1308

O’Meara, Seumas, WS 1504

Newspapers

Westmeath Independent, 23/10/1920

Westmeath Independent, 30/10/1920

Westmeath Examiner, 12/02/1921

This exodus from the RIC prompted the Ballymore Council to pass a resolution at its monthly meeting on 19th August 1920, congratulating the policemen who had resigned. Its following resolution was telling: an agreement to strike a rate of pay for the upkeep of the Irish Volunteers, or the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as the organisation had renamed itself. After all, it was the IRA, not the RIC, who were now performing the policing duties in Ballymore as well as the rest of Co. Westmeath.

This exodus from the RIC prompted the Ballymore Council to pass a resolution at its monthly meeting on 19th August 1920, congratulating the policemen who had resigned. Its following resolution was telling: an agreement to strike a rate of pay for the upkeep of the Irish Volunteers, or the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as the organisation had renamed itself. After all, it was the IRA, not the RIC, who were now performing the policing duties in Ballymore as well as the rest of Co. Westmeath.

It was not until mid-1920 that operations against RIC barracks by the Athlone Brigade were actually implemented. Even then, the majority of these were after their garrisons had been evacuated, making their destruction a relatively easy accomplishment.

It was not until mid-1920 that operations against RIC barracks by the Athlone Brigade were actually implemented. Even then, the majority of these were after their garrisons had been evacuated, making their destruction a relatively easy accomplishment.

On 4th November 1921, Michael Collins, as Director of Intelligence, wrote to the staff of the Mullingar IRA Brigade in Co. Westmeath. He had received a troubling letter about the arrests of two of its Volunteers: Patrick Dowling on 21st September, followed by Christopher Kelleghan on 22nd. Both had been singled out for subversive activities when they attempted to contact the GHQ of the IRA in Dublin.

On 4th November 1921, Michael Collins, as Director of Intelligence, wrote to the staff of the Mullingar IRA Brigade in Co. Westmeath. He had received a troubling letter about the arrests of two of its Volunteers: Patrick Dowling on 21st September, followed by Christopher Kelleghan on 22nd. Both had been singled out for subversive activities when they attempted to contact the GHQ of the IRA in Dublin.

By November, O’Sullivan had gathered enough preliminary evidence to proceed with an inquiry, to be held in Mullingar. The two co-defendants, for the inquiry was as much their trial, were present. O’Sullivan examined them and took their statements along with those from three of the others who had been dismissed from their Company.

By November, O’Sullivan had gathered enough preliminary evidence to proceed with an inquiry, to be held in Mullingar. The two co-defendants, for the inquiry was as much their trial, were present. O’Sullivan examined them and took their statements along with those from three of the others who had been dismissed from their Company. One possible lesson to take from this book is that politics is something best left to politicians. Shortly after the 1957 electoral defeat of John A. Costello’s second and final coalition government, the former Taoiseach was walking along the Dublin quays with two other senior Fine Gael men, James Dillon and Patrick Lindsay.

One possible lesson to take from this book is that politics is something best left to politicians. Shortly after the 1957 electoral defeat of John A. Costello’s second and final coalition government, the former Taoiseach was walking along the Dublin quays with two other senior Fine Gael men, James Dillon and Patrick Lindsay.