Vote for McGuinness who is a true Irishman,

Because he loved Eireann and fought in her cause,

And prove to the Party and prove to the world,

That Ireland is sick of her English-made laws.[1]

(Sinn Féin election song)

The Changing of the Guard

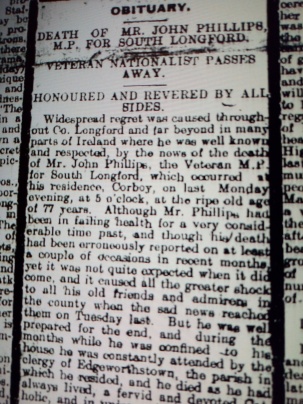

It was not the first time that the death of John Phillips had been reported, having been erroneously done so twice before the 2nd April 1917, when the long-standing Member of Parliament (MP) for South Longford, who had been in poor health for some time, breathed his last at the age of seventy-seven. It was the end of an era in more ways than one.

“During his long career he was one of the staunchest Nationalists in Co. Longford, and in his earlier days he was one of the most vigorous,” reported the Longford Leader. Phillips had been a leading Fenian in the county before choosing, like so many of his revolutionary colleagues, to throw his support behind the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), under the leadership of Charles Stewart Parnell, as a constitutional alternative when the physical force methods of the Fenians appeared to be going nowhere.

During the Parnell Split of 1890, Phillips remained loyal to his leader. It was a choice that placed him in the political minority, a characteristic decision, considering how, throughout the years, Phillips proved willing to put himself at odds with others, as alluded to gently in his obituary:

At times he might have differed from some of the local national leaders, yet there was never at any time one who was not prepared to acknowledge the honest and well meaning intentions of Mr Phillips.

The voters evidently agreed as they elected Phillips, first to the Chairmanship of Longford County Council in 1902, and then as their MP in 1907, a role he held until his demise. It had been an eventful life and a worthy career, but power abhors a vacuum and the question now was who would replace him.

And a fraught question it was, for the upcoming by-election would take place in a very different environment to when Phillips entered the political stage. For one, the electoral franchise had been expanded, ensuring that it now “embraces all classes in the community, and from the highest to the lowest, every man on the voters list will be entitled to cast his vote for the man of his choice.”

This was a heady responsibility indeed and, deeming itself duty-bound to offer a few words of advice, the Longford Leader urged for a spirit of inclusivity:

Let every man whoever he may be, be heard at the coming election with respect and without any stifling of free speech. Let the electors be given an opportunity of hearing to the full the pros and cons of the different arguments put forth by each side…If the electors follow these lines we are quite confident that the election will not be a curse but a blessing to this part of Ireland.[2]

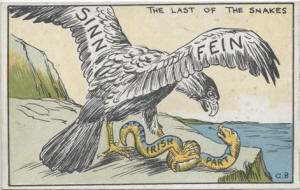

Noble words, but confidence was one thing the newspaper and its political patrons in the Irish Party were lacking. Times had changed and, more than that, the electoral franchise had shifted with it, as the once-almighty IPP found itself under threat from a new and hungry challenger.

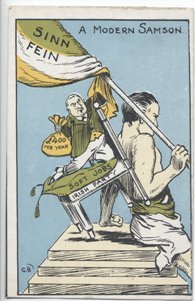

“It is announced in Longford that Mr. John MacNeill, who is at present in penal servitude, will be put forward as Sinn Fein candidate for the vacancy,” read the Irish Times, printing in italics the name the IPP least wanted to hear.[3]

‘An Issue Clear and Unequivocal’

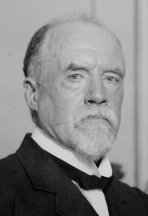

None were more conscious of the looming threat to the Irish Party’s hegemony – and, indeed, its survival – than its Chairman.

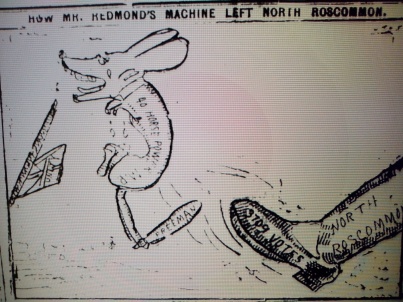

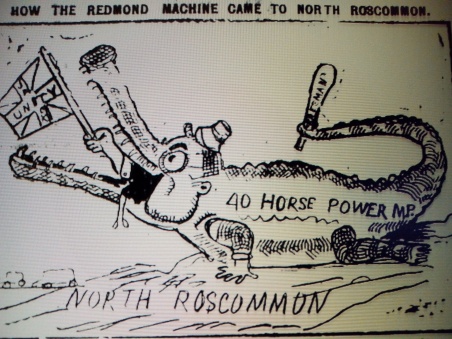

“The remarkable and unexpected result of the election in North Roscommon has created a situation in which I feel it my duty to address you in a spirit of grave seriousness and of complete candour,” John Redmond wrote on the 21st February 1917 in what was intended as a letter to the press, to be read by the Party faithful, still reeling from the shocking defeat eighteen days ago on the 3rd February, when Count George Plunkett scored a victory at the aforementioned by-election.[4]

And a crushing victory it was, with the dark horse candidate trouncing his IPP opponent by 3,022 votes to 1,708, more than twice as much. As if to rub salt into the wound, Plunkett had promptly declared his intent to abstain from taking his seat in Westminster, an antithesis to the strategy the Irish Party had long pursued towards its Home Rule goal since Parnell. This announcement of the Count’s had come as a surprise to many in his constituency, as their new MP had said little during his campaign, having not even been present in Roscommon until two days before polling.

He had been in England for the most part, exiled there by the British authorities on suspicion of his role in the Easter Rising, ten months ago. Such punishment had been mild compared to that of his son’s, Joseph Plunkett, executed by firing squad, and it was seemingly as much due to empathy for a father’s loss as anything political that the Count succeeded like he did.[5]

Which raised a question Redmond felt compelled to ask.

“If the North Roscommon election may be regarded as a freak election, due to a wave of emotion or sympathy or momentary passion,” he wrote, “then it may be disregarded, and the Irish people can repair the damage it has already done to the Home Rule movement. If, however –” and it was a big ‘if’ – “it is an indication of a change of principle and policy on the part of a considerable mass of the Irish people, then an issue clear and unequivocal, supreme and vital, has been raised.”

On the Defence

What followed in the letter was a brief rumination on recent history, from the start of the Home Rule movement in 1873 to its recent acceptance by Westminster in 1914. With the promised gains of a self-governing Ireland, free from the diktats of Dublin Castle:

It is nonsense to speak of such an Act as this as worthless. Its enactment by a large majority of British representatives has been the crowning triumph of forty years of patient labour.

True, Home Rule hung in suspension, not yet in effect, but only, Redmond assured his readers, until the end of the current war in Europe. And yes, there remained the ‘Ulster question’, with truculent Unionists threatening partition, but Redmond was confident that this would be “quite capable of solution without either coercion or exclusion.”

What otherwise was the alternative? If physical force methods were to take the place of constitutional ones, and withdrawal from Westminster adopted in support of complete separation, the consequences would be:

Apart from inevitable anarchy in Ireland itself, not merely the hopeless alienation of every friend of Ireland in every British party, but leaving the settlement of every Irish question…in the hands of Irish Unionist members in the Imperial Parliament.

Whether the electorate cared about such details, however, was yet to be answered. Redmond was honest enough to admit the central weakness of his party, namely that it had been around for so long, with the resulting “monotony of being served for 20, 25, 30, 35 or 40 years by the same men in Parliament.”

If so, Redmond was prepared to make capitulation into a point of principle, as he closed his letter with the following proclamation: “Let the Irish people replace us, by all means, by other and, I hope, better men, if they so choose.”[6]

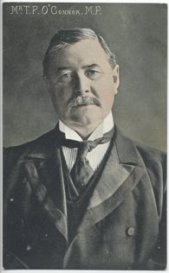

It was probably because of this depressing note on which it ended, reminiscent of a disgraced Roman about to enter a warm bath and open his veins, that three of Redmond’s colleagues – John Dillon, Joe Devlin and T.P. O’Connor – met to dissuade their leader from publishing the missive. Redmond could wallow in all the gloom and doom he liked, but the Irish Party was not yet done and its adherents, as was to be shown in South Longford, remained ready to slug it out to the bitter end with the Sinn Féin challenger.[7]

Teething Troubles

Flush with success following the Roscommon breakthrough, the victors were nonetheless going through their own bout of second-guessing each other. As president, Arthur Griffith, had summoned the Sinn Féin Executive, co-opting a few more members, but “no one seemed to know what to do,” recalled Michael Lennon, one of the new Executive inductees. “Sinn Féin had three or four hundred pounds in the bank but organisation there was none.” Instead, “things political were somewhat chaotic just now.”

Compounding problems was the same man who had achieved their first victory. While Plunkett was happy to use the Sinn Féin name for his Roscommon campaign, he evidently did not consider himself beholden to the party, as he was soon busy setting up a network of his own, as Lennon described:

Count Plunkett and his friends were organising a Liberty League with Liberty Clubs, but this was being done without any reference to Sinn Féin or to Mr. Griffith, then probably the best-known man out of gaol.

Griffith had the brand recognition but not the political muscle, nor did his powerbase: “It is now abundantly clear that at this stage the founder of the Sinn Féin movement had a large but scattered following.”

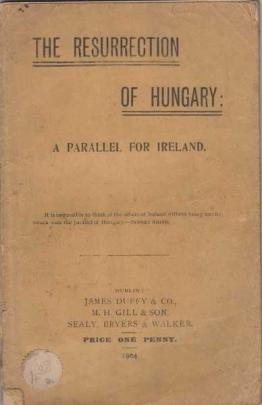

Worse, the ardent republicans who were flocking to the Sinn Féin banner had little time for the Sinn Féin president. His proposed model for Irish self-rule, a ‘dual-monarchy’ akin to the Austria-Hungarian one, married to a return of the 1782 Constitution between Westminster and Ireland, ensued that he was seen as only another compromiser in their eyes, and they did not bother hiding how they regarded:

…Mr. Griffith with unconcealed contempt and aversion, referring to him and his friends as the “1782 Hungarians,” a clownish witticism at the expense of a policy which, at least, ensured a practical method of securing Ireland’s recognition as a sovereign state from England.

Even though some time had passed when he put pen to paper, Lennon burned with the injustice of it all.[8]

The Plunkett Convention

Still, the two leaders were able to keep their growing rivalry out of public view – that is, until the 19th April 1917, when delegates from the various Sinn Féin branches throughout the country – accompanied by representatives from the Irish Volunteers, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, Cumann na mBan and the Labour Party – gathered inside the Mansion House, Dublin. The large clerical presence was also noted, as were, according to the Irish Independent, “many ladies and gentlemen well-known in literary and artistic circles.”[9]

They had all come in response to an open invitation by Plunkett, who, fittingly enough, presided over the assembly as the Chair. He was soon to make clear just how seriously he took his authority.

“The meeting was like all political meetings of Irishmen,” wrote Lennon witheringly:

In the early stages there were pious utterances about freedom and the martyred dead, all present cheering and standing. Then, after the platitudes had been exchanged, sleeves were tucked up.[10]

Onstage, in full view of the attendees, Count Plunkett locked horns with Griffith. The main point of contention was how and in what shape the new movement was to proceed, with the latter favouring an alliance of like-minded groups under the umbrella-name of Sinn Féin, against the Count’s preference to start anew in the form of his Liberty Clubs.

On the question of abstentionism, Plunkett was adamant – on no account would they send any more Irish representatives to Westminster, a point on which Griffith was apparently less dogmatic, to judge from his silence over it. As the tensions mounted, Griffith took Plunkett aside – and then announced to a shocked audience that the other man had denied him permission to speak.[11]

“Callous and Disdainful”

Lennon could not but cringe as he remembered how:

There was something of a scene, dozens rushing to the platform and everyone saying that the leaders must unite…The scene was most discouraging, and I think the delegates who had come from the country were rather disappointed at the obvious division among prominent people in Dublin.[12]

With the movement teetering on a split barely after its inception, Father Michael O’Flanagan stepped in. The priest had played a leading role in Plunkett’s election in Roscommon, where he had distinguished himself as a speaker and organiser. Such talents had earned him the respect of everyone involved, making him ideally suited to play the role of peacemaker. After a quiet word between him and Griffith, it was agreed that a committee be formed, consisting of supporters of both Griffith’s and Plunkett’s, including delegates from the Labour movement.

With this ‘Mansion House Committee’ serving as a venue for both factions to each have their say, Sinn Féin would continue organising about the country, as did Plunkett’s Liberty Clubs. It was not an ideal solution, more akin to papering over the cracks than filling them in, but it allowed the convention to end in a reasonably dignified manner.

Besides, there was still the common enemy to focus on. Before the convention drew to a close, Griffith read out an extract from a letter by Sir Francis Vane, who had exposed the murder of civilians by British soldiers during Easter Week. Vane met with Redmond in the House of Commons on the 2nd May 1916, before the executions of the Rising leaders took place. Redmond, Vane believed, could have used his influence to save their lives, and yet did not. Instead, his manner, Vane wrote, had been “callous and disdainful.”

Griffith let that sink in. “This man,” he said, twisting the knife, “should be smashed.”[13]

The Most Important Thing

Afterwards, Griffith and a few others withdrew to the front drawing-room of 6 Harcourt Street, where Sinn Féin had its offices. Father O’Flanagan was reading out a poem he had written for use at the Longford election when the door was thrown open and a pair of men strode in, one strongly-built, the other frail and sickly. It was Michael Collins and Rory O’Connor, two of the strident young republicans from Count Plunkett’s hard-line faction. As was to be typical of him, Collins took the lead in speaking.

“I want to know what ticket is this Longford election being fought on,” he demanded as soon as he caught sight of Griffith, seated in the middle of the room. Griffith was unperturbed as he smoked his cigarette, but whatever answer he gave – Lennon could not remember the specifics – only infuriated Collins.

“If you don’t fight the election on the Republican ticket,” he thundered, “you will alienate all the young men.”

Lennon, for one, was taken by surprise:

This was likewise the first time I heard anyone urge the adoption of Republicanism in its open form as part of our political creed. Mr. Griffith remained silent and composed. Mr [Pierce] McCann suddenly intervened by asking: “Isn’t the most important thing to win the election?”

Collins treated this as the foulest of heresies. The Roscommon election had been conducted under the Republican flag, he railed, and so the same must be done in Longford. Having played the diplomat before, Father O’Flanagan tried again:

He said that although the tricolour was used at Roscommon, the idea of an independent Republic was not emphasised to the electors, and that the people had voted rather for the father of a son who had been executed.

With neither side giving away, the argument cooled somewhat, enough for Collins, his piece thus said, to withdraw with a wordless O’Connor to a nearby table, where they counted out the donations from the Convention. But the question was not yet settled, with neither Collins nor Plunkett appearing the type to let it drop.

“It was difficult to work in harmony,” Lennon wrote with feeling.[14]

Choosing

Among the many remaining matters to resolve, the most pertinent for Sinn Féin was who was to be its candidate in South Longford – or, indeed, if there was to be one at all. The Irish Times had first announced Eoin MacNeill, the imprisoned Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers, but his controversial decision to cancel the 1916 Rising at the last minute, leading to a clash of orders and general confusion, made him too controversial a choice within the revolutionary movement.

At a meeting with Count Plunkett, Michael Collins, Rory O’Connor and the trade unionist William O’Brien, Griffith proposed J.J. O’Kelly, the writer and editor, better known by his pen-name ‘Sceilg’. South Longford would be a harder nut to crack than North Roscommon, Griffith warned, being an IPP bastion as well as a generous contributor of recruits to the British Army. O’Kelly’s role as editor to the Catholic Bulletin, a journal sympathetic to their cause, should at least be a start in countering these disadvantages.[15]

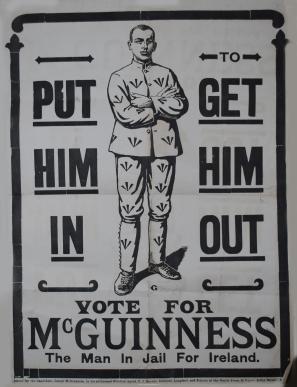

The others disagreed, preferring that a prisoner from the Rising should be their man, and so they settled on Joe McGuinness, a man otherwise unknown to the public. The decision made, Sinn Féin moved swiftly, and the Irish Times reported on how, less than a week after John Phillips’ death:

At a conference of Sinn Fein representatives in Longford on Saturday [7th April], Mr. Joseph McGuinness, a draper in Dublin, who is now undergoing three years’ imprisonment in connection with last year’s rebellion in Dublin, was selected as their candidate in South Longford.[16]

However, it seemed that the said representatives had neglected to inform McGuinness of his nomination before making it public. A couple of days later, the selection committee was called together again with the news that the inmates in Lewes Prison, England, where McGuinness was housed, had decided that none of them would stand in any election.

Objections

As O’Brien recalled: “We were very disconcerted at this announcement.” Their grand scheme to dethrone the IPP and revise the game-plan for Irish freedom looked in danger of being stopped in its tracks. In response, the committee sent an emissary over to Lewes to contact McGuinness through the prison chaplain:

Michael Staines was selected for this job and it was subsequently learned that the statement was correct but when our message reached McGuinness the matter was re-discussed and it was decided to leave each prisoner free to accept or reject any invitation he might receive to contest a parliamentary constituency, and so we went ahead with McGuinness as candidate.[17]

Further details on the controversy were provided in later years by Dan MacCarthy, a 1916 participant who had been sent out to Longford to help manage the Sinn Féin campaign, setting up base in the Longford Arms Hotel. Initial impressions were not encouraging – they had no funds and little in the way of organisation but, after forming an election committee of his own, including the candidate’s brother, Frank, and his niece, and hiring a few cars, they were able to drive through the area, setting up further committees of supporters as they did so to help shoulder the workload.

In a taste of the ferocity to come, they were attacked in Longford town after returning from a meeting by a crowd consisting mostly of women. There was no love lost between Sinn Féin and the dependents of Irishmen serving abroad in the British Army, or ‘separation women’ as these wives were dubbed, and a member of MacCarthy’s party needed stitches after being struck on the head with a bottle.

Secrets Kept

At least Sinn Féin had the advantage of having the one candidate to promote. The Irish Party, on the other hand, wasted precious time vacillating between three prospective names. “I think that this was responsible for our eventual success,” MacCarthy mused.

He was hard at work when Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith arrived unexpectedly to see him, bringing the unwelcome news that a letter had come in from McGuinness, demanding that his name be withdrawn:

Collins and Griffith added that they had not mentioned this to anybody in Dublin and that I was the first to know of it. I said: “What are you going to do?” and they said they were going on with it for the reason that a man in gaol could not know what the position was like outside.

Still, it was not a secret that could be kept forever. MacCarthy, acutely aware of the damage this sort of publicity could do, suggested that they find themselves a printer they could rely on to keep quiet. As they did not know of any in Longford, MacCarthy decided that they should go outside the county, to Roscommon, and meet Jaspar Tully, a local bigwig who owned, among other things, a printing press for his newspaper, the Roscommon Herald.

Tully was not the most obvious of allies, for he had run as the third candidate in the North Roscommon election against Plunkett but, while he was not of Sinn Féin, he loathed the IPP, and that was enough. MacCarthy, Collins and Griffith wrote up a handbill, explaining the Sinn Féin position should McGuinness’ decline become public knowledge, and had 50,000 copies printed in Roscommon in readiness.

MacCarthy’s instinct for who to trust had proved correct:

The secrets of this handbill was well kept by Jaspar Tully and his two printers. Although they worked all night on it and knew precisely what its contents were, they disclosed nothing.

As it turned out, the handbill was not needed. MacCarthy learnt that the Lewes prisoners had had a rethink and, while the majority remained convinced that parliamentary procedure was not for them, a significant minority decided to trust their comrades at liberty – significant enough, in any case, for McGuinness to keep his name on the ballot and allow Sinn Féin to proceed with its campaign. MacCarthy and his colleagues could breathe a sigh of relief.[18]

‘A Most Deplorable Tangle’

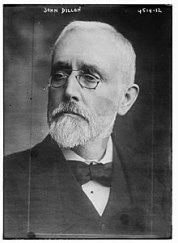

The Irish Party, meanwhile, were showing themselves to be far less adroit at hiding their disarray. Redmond was suffering from eczema – an apt metaphor for the state of his party – when he received a letter from John Dillon, the MP for East Mayo. Writing on the 12th April, Dillon warned him that “the Longford election is a most deplorable tangle.”

And no wonder, given that they had yet to decide on the most important question: “All our reports go to show that if we could concentrate on one candidate we could beat Sinn Fein by an overwhelming majority.”

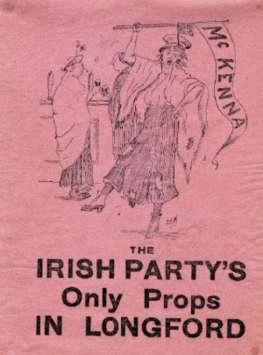

Instead of one contender to rally behind, the Parliamentary Party was split between three competing ones: Patrick McKenna, Joseph Mary Flood and Hugh Garrahan.

Meanwhile, “the Sinn Feiners are pouring into the constituency and are extremely active, and we of course can do nothing.” For Dillon, the whole mess “most forcibly illustrates the absolute necessity of constructing without delay some more effective machinery for selecting Party candidates.”[19]

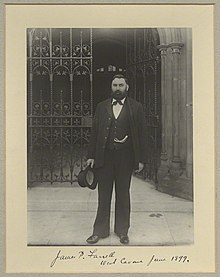

Which was an extraordinary statement. Dillon was speaking as if he and his Chairman were complete greenhorns entering politics for the first time. The Longford Leader bemoaned the “lassitude and indifference which has led to the decline of the Irish National Organization” in the county. Had the IPP adherents listened to the advice of J.P. Farrell, the MP for North Longford – not to mention the newspaper’s proprietor – and held a national convention to settle the question of the candidacy, it could have:

…defied any ring or caucus or enemy to defeat them. Now they are faced with not one but many different claimants between whom it is impossible to say who will be the successful one.

If the matter was not solved, and soon, the Longford Leader warned, then the election might very well result in a Sinn Féin win. If so:

It will be further evidence for use by our enemies of the destruction of the Constitutional Movement and the substitution of rebellion as the National policy. And yet we do not believe that any sane Irishman, and least of all the South Longford Irishmen, are in favour of such a mad course.[20]

Not that the Irish Party could take such sanity for granted. Acutely aware of the growing peril, its leaders scrambled for a solution. On the 13th April, Dillon wrote to Redmond about a talk he had had with Joe Devlin, their MP for Belfast West: “We discussed your suggestion about getting the three candidates to meet.”

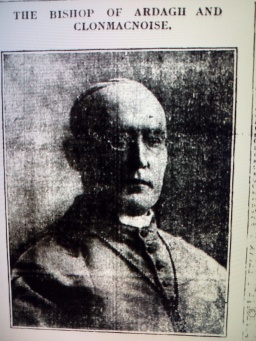

Dillon was also wondered whether it would be worthwhile to send someone to meet the Most Rev. Dr Joseph Hoare, the Bishop of Ardagh, though the lukewarm Church support received so far enraged Dillon. “The blame of defeat of the constitutional cause will lie on to the Bishops and priests who split the Nationalist vote,” he fumed.

A Decision Made

It says much about the level of lethargy the IPP had sunk to that it was not until the 21st April, more than a week since his last letter, that Dillon could inform Redmond that McKenna, Flood and Garrahan had agreed to stand down and leave the selection process in the Chairman’s hands.[21]

Four days later, Redmond was able to write to Dr Hoare that McKenna had been picked to run as the IPP’s sole candidate. In contrast to Dillon’s choice words about workshy clergy, Redmond took care to thank the Bishop profusely

I need scarcely say how grateful I am to your Lordship for your action in this matter…another added to the many services which you have given to the Irish Cause, and the Party and the Movement will be forever grateful.

The Bishop of Ardagh was similarly appreciative in his own letter the day after: “We will all now obey your ruling, and strive for Mr. McKenna. I hope we shall reverse the decision of Roscommon.”

Conscious of the fragility of both Redmond and the party he led, Dr Hoare added: “I hope you will soon be restored to perfect health, and that your policy and Party will remain, after the Physical Force had been tried and found wanting.”[22]

The Bishop added his public backing to the private support on the 4th May, when he signed McKenna’s papers inside the Longford courthouse. Elsewhere in South Longford that day, at Lanesborough and Ballymahon, some men who were putting up posters for McKenna were pelted with stones and bottles by a crowd and their work torn down.

Tricoloured ‘rebel’ flags could be seen flying from trees, windows and chimneys all over the contested constituency, save for the town of Longford. But even there held no sanctuary for the IPP, as one of its supporters, John Joseph Dempsey, was put in critical condition from a blow to the head, delivered in public on the main street.[23]

Escalation

Despite such incidents, the Irish Times believed that the election so far had been “rather tame.” That changed with the arrival, on the 5th May, of four MPs: John Dillon and Joe Devlin for the IPP, as well as Count Plunkett and Laurence Ginnell on behalf of Sinn Féin, at the same time and at the same station. Rival crowds had gathered to greet their respective champions but, despite some confusion on the platform, the two factions were able to withdraw to their separate hotels in an orderly manner.

This lull did not last long. Later that day, as speeches were being delivered in front of the hotel that served as the IPP headquarters, a pair of motor cars drove towards the audience, the tricolours fluttering from the vehicles marking their occupants as Sinn Féiners. The crowd parted to allow through the first car, possibly out of chivalrous deference to its female passengers, but the second vehicle was mobbed as it tried to follow, with the loss of one of its tricolours, torn away before the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) could intervene and prevent worse.

By the next day, the 6th May, the Irish Times had found that:

Longford was crowded with partisans, who seem to have flocked to their separate standards from all parts of Ireland…The flags of the rival parties are displayed at every turn, and incessant party cries become grating to the ear. Nothing is being left undone by either side to further its prospects.

The newspaper judged Sinn Féin to be the superior in terms of organisation, with more speakers at hand than needed and a fleet of motor cars at their disposal. But the IPP appeared to be making some overdue headway, particularly in Longford town, where Dillon and Devlin were due to speak.

A procession of their supporters were preparing to set off for the rally when a line of cars, bedecked with green, orange and white flags, drove into view. As before, a rush was made by the crowd to seize the offending tricolours, and a melee ensued as the passengers fought back. Sticks were wielded and stones thrown, until the RIC again came to the rescue and forced a passage through the press of bodies for the vehicles to motor past.

Order had been restored – until, that is, the IPP procession, en route to hear Dillon and Devlin, again encountered the same Sinn Féin convoy, and another scrum unfolded in the street.[24]

Choices

“The opposition was particularly strong in Longford town,” remembered Kevin O’Shiel, a Tyrone-born solicitor and Sinn Féin activist. “Indeed, it was quite dangerous for any of us to go through the streets sporting our colours.” There, and in the other towns of the county, the IPP could finally flex its muscles again, with rallies that “were larger and more enthusiastic than ours, all colourful with Union Jacks and flags.”[25]

At one such event, on the 7th May, Dillon took the stage in the market square of Longford town to make the case for the constitutional movement. The issue was now clear, he said. In North Roscommon, there had been no such clarity. The electors there had voted for Count Plunkett out of sympathy for the hardships the old gentleman had endured by the loss of his son and his own exile. No political case had been made by the Count’s supporters, not even a warning that he would refuse to take his seat at Westminster.

But now, in contrast, South Longford was faced with a clear choice: to continue the pursuit of Home Rule, and the connection with Great Britain that it entailed, or abandon that in favour of complete separation in the form of an Irish Republic.

The latter policy was nothing novel. Others had previously tried to force it on Parnell, heaping on him the exact same abuse now levelled at Redmond: he was a traitor, he was a sell-out, a tool of British imperialism and so on. Yet, as history showed, the alternative to the slow-but-steady approach produced only disaster:

If the constitutional party were driven from the battle, and the counties were to adopt the program of Sinn Fein and the Republican Party, it could only have one result in the long run – an insurrection far more widespread and bloody than the rising of last year, followed by a long period of helplessness and brutal Orange ascendancy, such as followed 1798 and 1848.

Contrary to what was being said in regards to the Rising, the Irish Party had not been negligent, continued Dillon. There were thirty men now alive thanks to the efforts their MPs had made in saving them from a firing-squad. While sixty others languished in penal servitude, there would have been over three hundred in such a plight, including the prisoners freed from Frongoch five months ago, had it not been for the IPP:

The party did not look for gratitude, nor expect it, for their action in these matters, but solid facts could not be dislodged by lies, no matter how violently their opponents screamed.

Joe Devlin was up next. Echoing his colleague, the MP for Belfast West posed his audience two stark choices: the Constitutional movement or armed rebellion, with no halfway house possible. The former had brought Ireland to the brink of self-rule through bloodless means. Were they to cast that aside in favour of a violent gamble for an impossible end? Ireland had had enough of war, Devlin said. It wanted peace.[26]

Joe Devlin

At least one foe in the crowd was impressed. “Joe was an extremely eloquent speaker with an extraordinary emotional ring in his penetrating tenor voice,” Kevin O’Shiel recalled, “which his sharp Belfast accent accentuated, particularly to southerner ears.”

The Ulsterman was also willing to role his sleeves up in a fight. Reaching into his bag of oratorical tricks, he waved a large green banner, adorned with the national symbol of a harp in gold, declaring:

Here is the good old green flag of Ireland, the flag that many a heroic Irishman died under; the flag of Wolfe Tone, of Robert Emmet, of Thomas Davis; aye, and the flag of the great Charles Stewart Parnell.

As his audience applauded, Devlin moved in for the rhetorical kill:

Look at it, men and women, it has no yellow streak in it, nor no white streak. What was good enough for Emmet, Davis and Parnell is good enough for us. Long may it fly over Ireland![27]

Devlin clearly did not intend to leave the ‘green card’ entirely for the challenger’s use. He and Dillon departed from Longford on the following day, the 8th May, the latter needed for his parliamentary duties in Westminster. He was confident enough to write to Redmond, proclaiming how:

Our visit to Longford was a very great success [emphasis in text]. So far as the town and rural district of Longford goes, we are in full possession. Our organizers are very confident of a good majority.

Nonetheless, he signed off on a jarringly worrisome note: “If in the face of that we are beaten, I do not see how you can hope to hold the Party in existence.” The use of ‘you’ as the pronoun hinted at how Dillon, a consummate politician, was already shifting any future blame on to someone else.[28]

Fighting Flags

Devlin was not the only IPP speaker to distinguish himself with turns of phrase and a willingness to make an issue out of flags. “Rally to the old flag,” the MP for North Longford, J.P. Farrell, urged his listeners. “Ours is the old green flag of Ireland, with the harp without the crown on it. There is no white in our flag, nor no yellow streak.”

Another slingshot of his was: “Don’t be mad enough to swallow this harum scarum, indigestible mess of pottage called Sinn Féin. You will be bound soon after to have a very sick stomach, and jolly well serve you right.”[29]

Another Member of Parliament – Tommy Lundon of East Limerick, O’Shiel thought, though he was not sure by the time he put pen to paper for his memoirs – went further when he proclaimed how the tricoloured flags the opposition were so fond of waving had, upon inspection, revealed themselves to have been made in Manchester.

“There’s Sinn Féin principles for you,” he crowed.[30]

The other side, meanwhile, were giving as good as they got. When a number of Irish Party MPs and their supporters arrived in Longford by train, they were met at the station by a crowd of children carrying Union Jacks.

To their excruciating embarrassment, in an election where the definition of Irishness was as much at stake as a parliamentary seat, the newcomers had to march through town accompanied by a host of the worst possible colours to have in Ireland at that time. The culprit was a Sinn Féin partisan who had bought the Union Jacks in bulk and handed them out to whatever children he could find, the young recipients being delighted at the new toy to wave.

“The Sinn Féin election committee was not responsible, but the IPP did not know that and they were very angry,” according to one Sinn Féin canvasser, Laurence Nugent. It was a low trick but Nugent was unsympathetic. “But why should they [be]? It was their emblem. They had deserted all others.”

It was a point Nugent was more than happy to press. When John T. Donovan, the MP for West Wicklow, was on a platform speaking, Nugent called out from the crowd, asking whether Donovan would admit that Redmond had sent him a telegram on the Easter Week of the year before, with orders to call out the National Volunteers to assist the British Army in putting down the Rising.

When a flummoxed Donovan made no reply, not even a denial, there were shouts of ‘Then it’s true’ from the onlookers. Nugent could walk away with the feeling of a job well done.[31]

‘Clean Manhood and Womanhood’

The scab of 1916 was further picked at by Laurence Ginnell, the maverick MP for North Westmeath who had thrown himself into the new movement. Speaking at Newtownforbes – an audacious choice of venue, considering that it was McKenna’s hometown – on the same day as Dillon and Devlin, the 8th May, Ginnell repeated the allegation that the IPP representatives had cheered in the House of Commons upon hearing of the executions of Rising rebels.

While not saying anything quite as inflammatory, his partner, Count Plunkett, likewise wrapped himself in the mantle of Easter Week. “I would not be here today,” he told his listeners. “If I thought the people of South Longford had anything of the slave in them. To prove they are not slaves, let them go and vote for the man who faced death for them.”

Other Sinn Féin speakers there included his wife, Countess Plunkett, and Kathleen Clarke, widow of the 1916 martyr. They returned to Longford town in a convoy of thirty, tricolour-decked cars, cheered at different points along the way – that is, until they reached the main street, where a different sort of welcome had gathered. ‘Separation women’, armed with sticks, rushed the cars, singling out the one with the Count and Countess Plunkett, and Ginnell, on board, while pelting the Sinn Féiners with stones, one of which struck the Countess in the mouth, while their chauffeur was badly beaten.

Throughout South Longford, the RIC found itself frequently called upon to step in and prevent such brawls from escalating. Other notable victims of the violence raging through the constituency were the visiting Chairman of the Roscommon Town Commissioners, and Daniel Garrahan, uncle to one of the original IPP candidates, who was held up in his trap and pony, and assaulted.[32]

“Party fighting for their lives with porter and stones,” Ginnell wrote to his wife in a telegram. But he was undeterred. “Clean manhood and womanhood will prevail.”

Ginnell received a telegram of his own from the Sinn Féin election committee, on the 8th May, warning him that an attack had been planned for when he left his accommodation. “In the circumstances we would suggest that it might be best not to leave the hotel this evening.”[33]

Not all encounters were violent. Patrick McCartan, a Sinn Féin canvassers, was able to observe a range of reactions:

Some of them were friendly. Some of them just told you bluntly that they were going to vote for McKenna. I remember a woman who was a staunch supporter of McKenna. Her husband was not in, but she knew McKenna and McKenna was a decent man, and they were going to vote for him and that was all about it.

Nonetheless, McCartan and the woman were able to part on good terms. As they shook hands, he asked her to pray for the freedom of Ireland. “God’s sake!” she exclaimed. “Ye may be right after all!”[34]

‘A Powerful Hold’

Amidst the noise and turmoil, the loyalties of two distinct demographics could be seen.

At the forefront of pro-McKenna crowds were the ‘separation women’. Their choice of Union Jacks for flags to wave was probably not appreciated by the Irish Party, but there was no doubting the women’s zest. An Australian soldier on leave found himself the centre of attention from a harem of admiring females, one of whom threw her arms around his neck and called: “May God mind and keep you. It’s you who are the real and true men.”[35]

On the other side, the young men of the constituency were standing with Sinn Féin, prompting the Irish Times to marvel at how:

The more closely one gets in touch with the situation in South Longford the more one is convinced that Sinn Féin has a powerful hold on the youth of the country. Whether the real import of its doctrine is understood is not clear. Indeed, the youthful mind is not inclined to bother about ascertaining it.

If every Longford youth had a vote, so the Irish Times believed, then Sinn Féin would win without a doubt. The generation divide had even entered family households, where it was reported that sons were refusing to help with farm work, and daughters striking on domestic duties, without first a promise from their fathers to cast a vote for McGuinness.

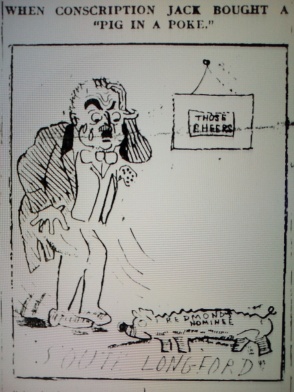

In some families, however, such bolshiness was not necessary, as Sinn Féin activists skilfully played on the fear of conscription, with warnings that every young man in the country would be called up for the British Army unless their candidate was elected. “This threat seems to be having its desired effect in remote rural districts, where farmers, apprehensive for their sons, will vote for Mr McGuinness.”

Not that the fight was finished. Thankfully for the Irish Party, sniffed the Irish Times, “youthful fervour does not count for much at the polling booths.”

Assisted by veteran campaigners, including MPs, the Parliamentary Party was working hard to make up for the slow start and the other side’s zeal, and could already claim the majority of votes in Longford town. The question now was whether this would be enough to offset the rural votes, the bulk of which were earmarked for McGuinness as shown by the number of tricolours festooning the branches of trees.[36]

South Longford was on a knife-edge, poised to tilt either way for McKenna or McGuinness – just the time for a dramatic intervention in the form of not one, but two, letters from the country’s highest spiritual authorities.

Episcopal Intervention

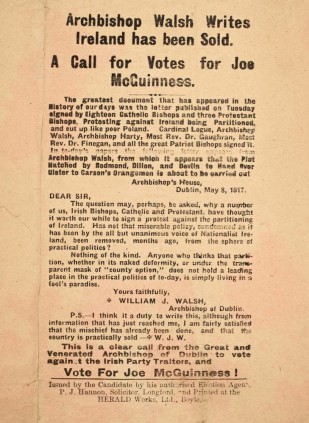

The first was an ecumenical piece, signed by eighteen Catholic bishops and three Protestant prelates. Topping the list of signatures was Cardinal Michael Logue, Primate of All Ireland, with Archbishop William Walsh of Dublin, Primate of Ireland, directly following, in a reflection of their place in the hierarchy of the Irish Catholic Church.

“Fellow countrymen,” the letter began:

As there has been no organised effort to elicit the expressions of Irish opinion regarding the dismemberment of our country, and it may be said that the authoritative voice of the Nation has not yet been heard on this question, which is one of supreme importance.

The dismemberment in question meant the proposed Partition of Ulster, specifically the six counties in the North-East corner with prominent Unionist populations, from the rest of Ireland. In the absence of any such organised efforts, the Princes of the Catholic Church and their Protestant allies moved to fill the leadership vacuum:

Our requisition needs no urging. An appeal to the Nationalist conscience on the question of Ireland’s dismemberment should meet with one answer, and one answer alone. To Irishmen of every creed and class and party, the very thought of our country partitioned and torn as a new Poland must be one of heart-rending sorrow. [37]

No reference was made to any particular political group. Yet no reader could have thought it anything but a criticism of the Irish Party, on whose watch in Westminster this Polandification was threatening to happen. Archbishop Walsh went further with a letter of his own, published in conjunction with that of his fellow clergymen:

Dear Sir,

The question may, perhaps, be asked, why a number of us, Irish Bishops, Catholic and Protestant, have thought it worth our while to sign a protest against the partition of Ireland. Has not that miserable policy, condemned as it has been by the unanimous voice of Nationalist Ireland been removed, months ago, from the sphere of practical politics?

Nothing of the kind. Anyone who thinks that partition, whether in its naked deformity, or under the transparent mask of “county opinion,” does not hold a leading place in the practical policies of to-day, is simply living in a fool’s paradise.

As a final sting, Dr Walsh added in a postscript:

I am fairly satisfied that the mischief has already been done, and that the country is practically sold.[38]

Practically sold? Again, no names were cited, but they did not have to be, and the Fourth Estate quickly picked up the cue. “The venerated Archbishop of Dublin, Dr Walsh, has sent out a trumpet call against the treachery that the so-called Irish Party are planning against Ireland,” thundered the Midland Reporter.

Those newspapers allied to John Redmond scrambled to respond, with the Freeman’s Journal taking the time to deny in a lengthy rebuttal the accusation that its patrons had ever thought of being acquiescent to a national carve-up. Which was only further proof of guilt, according to the Northern Whig: “As is evident from the troubled and rather incoherent comments of their official organ, the Redmondite leadership were as ready to partition now as they were last June.”[39]

‘Between Two Devils and the Deep Sea’

While most other news outlets did not venture quite that far, they were still in full agreement: Archbishop Walsh was the hero of the hour, Partition was a dead issue, and so was Home Rule if it fell short of anything but an intact Ireland. If His Grace was the instrument of this reversal, then the Irish Independent had been his mouthpiece in its publication of his letter.

The hostility of the newspaper was well-known to the IPP leadership. “Between the Sinn Fein, the anti-exclusionists of Ulster, and the Independent,” complained Dillon in a letter to T.P. O’Connor on the 19th August 1916, “we are between two devils and the deep sea [emphasis in text].”[40]

He and his colleagues might have brooded on the bitter irony of how the spectre of Partition was being used as a rod to beat them with; after all, they had lobbied as best they could in Westminster to prevent such a possibility. “Do settle the Irish question – you are strong enough,” Willie Redmond, brother of John, had urged the Prime Minister in a letter on the 4th March 1917:

Give the Ulster men proportional and full representation and they cannot complain. If there is no settlement there will be nothing but disaster all round for all.[41]

But David Lloyd George could not be budged into overriding the Orange veto. “There is nothing I would like better to be the instrument for settling the Irish question,” he told Willie silkily, two days later. “But you know just as well as I do what the difficulty is in settling the Irish question.”[42]

And that was that. Two months later, Nationalist Ireland was closing ranks against its former standard bearer, leaving the Irish Parliamentary Party out in the cold, while its challenger swooped in for the kill. A printing press in Athlone was used to publish the Archbishop’s damning words in pamphlet form, while Sinn Féin activists gleefully bought up every newspaper copy they could find with the letter, some bringing bundles of them from as far as Dublin, ready to be handed out in Longford on the morning of the 9th May – polling day.[43]

Final Judgement

The Irish Party could at least take solace in how it had not been completely deserted by the ecclesiastical powers, as Bishop Hoare entered the Longford Courthouse to cast his vote for McKenna. Cheers greeted His Grace’s arrival, though that might have been deference for a man of the cloth rather than support for his political stance, as there was further acclaim when a man called for applause for Archbishop Walsh.

As the polls closed at 8 pm, spokesmen for Sinn Féin anticipated a win by three hundred votes. More demurely, those for the IPP predicted a small minority for McKenna.[44]

In private, Dan MacCarthy had discussed the probabilities with Griffith. Whether a victory or loss, MacCarthy estimated it would be by a margin of twenty votes. Either way, it was going to be close.[45]

On the 10th May, MacCarthy watched as the ballots were collected inside the Courthouse to be counted by the Sub-Sheriff’s men. The one assigned to McKenna’s papers started by separating them into bundles of fifties but, when that seemed inadequate to the sheer volume before him, he switched to the system the McGuinness counter was using and piled them by their hundreds.

On the 10th May, MacCarthy watched as the ballots were collected inside the Courthouse to be counted by the Sub-Sheriff’s men. The one assigned to McKenna’s papers started by separating them into bundles of fifties but, when that seemed inadequate to the sheer volume before him, he switched to the system the McGuinness counter was using and piled them by their hundreds.

The high turnout was testament to the passions the election had inspired in South Longford. The hundred-strong batches of ballot papers for each candidate were piled criss-crossing each other, allowing for the Sub-Sheriff to make reasonable progress in counting. But not quickly enough for the IPP representative, who passed a slip of paper through the window before the Sub-Sheriff could declare his findings.

The paper read: McKenna has won.[46]

Kevin O’Shiel was among the crowds outside. When the Sinn Féin supporters saw the note:

We were dumbfounded, our misery being aggravated by the wild roars of the triumphant Partyites and their wilder “Separation Allowance” women who danced with joy as they waved Union Jacks and green flags.

O’Shiel was in particular dismay. After all, having bet ten pounds – a hefty amount back then – on McGuinness succeeding, he now looked to be leaving Longford a good deal poorer than when he had entered.[47]

Lost and Found

Inside the Courthouse, however, one of the Sinn Féin tallymen, Joe McGrath, was protesting that the count did not match the total poll. Seeing a glimmer of hope, MacCarthy demanded that the process be gone through again.[48]

Among those present was Charles Wyse-Power, a solicitor who had come to Longford on behalf of Sinn Féin in case the IPP tried declaring McGuinness’ candidacy invalid on the grounds of him being a convicted felon. Seeing their supporters, including Griffith, standing mournfully outside on the other side of the street, McGrath urged Wyse-Power to go and announce the decision for a recount, as much to reassure their side as anything.[49]

Wyse-Power did so. Calling for silence, he announced that a bundle of the votes had been overlooked and, as such, a recount was in order. Seeing that he might not be soon short a tenner after all, O’Shiel could only hope for the best:

A drowning man hangs on to a straw, they say, and we certainly (myself in particular) held with desperation on to the straw Charles had flung us.[50]

As it turned out, as MacCarthy described:

The mistake was then discovered that one of the bundles originally counting as 100 votes contained 150. Having discovered this, it tallied with the total poll, giving McGuinness a majority of 37.[51]

Frank McGuinness, standing in for his imprisoned brother, unfurled a tricolour from a window of the courthouse, shouting out that Ireland’s flag had won, to the cheers of his supporters and some flag-waving of their own. For all the jubilations, it had been a painfully close call. “I don’t think that McGuinness would have won that election had it not been for the letter of Archbishop Walsh,” said a relieved O’Shiel.[52]

MacCarthy was not so sure. The letter had come too late in the election to change anyone’s minds, he believed, which would already been made up by the time Sinn Féin workers were pushing printed copies of the Archbishop’s words into people’s hands on polling day. In his opinion, the delay of the IPP in selecting a sole candidate had been its losing factor.[53]

On that, he and the Longford Leader were in agreement. For even after McKenna had been chosen over Flood and Garrahan, the newspaper bemoaned:

The selected Nationalist Candidate had a great deal of uphill work to face, even while the other two candidates had withdrawn. As against the Party candidate the Sinn Feiner had a whole fortnight in which to over run the constituency and they did so in great style.

It was a moxie that even an avowed enemy like the Longford Leader was forced to admire:

For two consecutive Sundays they had the ear of the people at all the masses in all the chapels, and no one who knows how hard it is to get an Irishman to change his view once he has made his mind up but must admit that this was a serious handicap.[54]

But perhaps the explanation is as simple as the one offered by Joseph Good, a Sinn Féin activist: “This victory can be attributed to Joe McGrath’s genius for mathematics.”[55]

‘A Confusion of Factions’

Up, Longford, and strike a blow for the land unconquered still,

Your fathers fought their ruthless foe on many a plain and hill.

Their blood runs red in your Irish veins,

You are the sons of Granuaile.

So show your pride in the men who died,

And vote for the man in gaol.[56]

(Sinn Féin election song, South Longford, 1917)

Regardless of the whys and whats, a win was a win. The RIC on standby were drawing up between the two groups of partisans to prevent a repeat of the violence but that proved unnecessary. When McGuinness proposed a vote of thanks for the Sub-Sheriff and his team, the request was seconded by McKenna, who took his defeat with good grace, saying that, sink or swim, he would stand with his old party and old flag. That his defeat had been so close, he said, showed that the fire lit in North Roscommon had dwindled already to a mere flicker.

The Sinn Féiners, naturally, did not see things that way. The man of the moment, McGuinness, was absent, as much a guest of His Majesty in Lewes as ever, but others were there to inform the tricolour-bearing crowd, after they had returned to the Sinn Féin campaign headquarters in town, what that day’s result meant.

For Griffith, this had been the greatest victory ever won for Ireland at the polls, and in the teeth of stern opposition at that. Cynics had scoffed that Sinn Féin won North Roscommon only by concealing its aims – well, there could be doubting what such aims were now, Griffith declared.

Count Plunkett predicted that this was but the beginning, with more elections to follow that would sweep the IPP away. Privately, he and Griffith continued to loathe each other, and their struggle for the soul of Sinn Fein had not yet ended but, in the warm afterglow of success, they could put aside mutual acrimony – for now.

Elsewhere in the country, the results were nervously anticipated. When a placard was shown from a window of the Sinn Féin offices in Westmoreland Street, Dublin, the audience that had gathered there broke into applause. More crowds greeted the returning Sinn Féin contingents at Broadstone Station with waved tricolours, which were promptly seized by killjoy policemen, who dispersed the procession before it could begin.

Not to be deterred, a flag with the letters ‘I.R.’, as in ‘Irish Republic’, was flown above the hall of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in North Frederick Street. If Sinn Féin had shied away from running on an explicitly Republican policy, at least for now, then there were some who knew exactly what they wanted.

“Up McGuinness!” cried a party of students as they paraded through Cork, waving tricolours, while a counter-demonstration of ‘separation women’ dogged them, singing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ and ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’, in between cheers for the Munster Fusiliers and other Irish regiments their menfolk were serving in.[57]

In Lewes Prison, whatever doubts the captive Irishmen had had about the value of contesting elections were forgotten as their excitement at the news almost brimmed over into a riot. McGuinness was hoisted onto a table in a prison hall to make a speech, the building ringing with the accompanying cheers. It was only with difficulty that the wardens were able to put their charges back in their cells.[58]

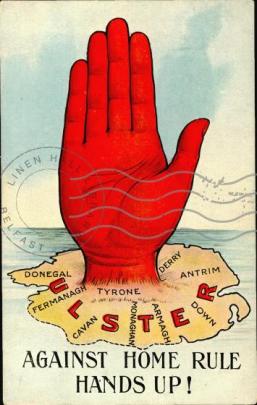

More muted was the reaction in Belfast, where the chief interest among Unionists was the impact the result would have on the Home Rule proposals, due to be submitted to Westminster in the following week. The odds of such a measure succeeding now looked as shaky as the IPP itself. If Archbishop Walsh’s intervention had hardened Nationalist Ireland against Partition, it equally made Protestant Ulster even more sure not to be beneath any new parliament in Dublin.

Indeed, Ireland looked more uncertain a place than ever. “The country is a confusion of factions,” read the Daily Telegraph. “A unanimous Nationalist demand, which could be faced, and which could be dealt with through an accredited leadership, no longer exists.” The old order may have been as dead as O’Leary in the grave, but what would come next had yet to be seen.[59]

See also:

An Idolatry of Candidates: Count Plunkett and the North Roscommon By-Election of 1917

Raising the Banner: The East Clare By-Election, July 1917

Ouroboros Eating Its Tail: The Irish Party against Sinn Féin in a New Ireland, 1917

References

[1] Doherty, Bryan (BMH / WS 1292), p. 5

[2] Longford Leader, 07/04/1917

[3] Irish Times, 04/04/1917

[4] Meleady, Dermot (ed.) John Redmond: Selected Letters and Memoranda, 1880-1918 (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018), p. 274

[5] Roscommon Herald, 10/02/1017

[6] Meleady, pp. 275-6

[7] Ibid, p. 274

[8] Lennon, Michael, ‘Looking Backward. Glimpses into Later History’, J.J. O’Connell Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI) MS 22,117(1)

[9] Irish Independent, 20/04/1917

[10] Lennon

[11] Freeman’s Journal, 20/04/1917

[12] Lennon

[13] Irish Independent, 20/04/1917

[14] Lennon

[15] O’Brien, William (BMH / WS 1766), pp. 105-6

[16] Irish Times, 10/04/1917

[17] O’Brien, pp. 106-7

[18] MacCarthy, Dan (BMH / WS 722), pp. 12-4

[19] Meleady, p. 277

[20] Longford Leader, 14/04/1917

[21] Meleady, p. 277

[22] Ibid, p. 278

[23] Irish Times, 05/05/1917

[24] Ibid, 07/05/1917

[25] O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770, Part 5), pp. 40-1

[26] Irish Times, 07/05/1917

[27] O’Shiel, p. 41

[28] Meleady, p. 278

[29] Irish Times, 07/05/1917

[30] O’Shiel, pp. 41-2

[31] Nugent, Laurence (BMH / WS 907), pp. 98-9

[32] Irish Independent, 07/05/1917

[33] Ginnell, Alice (BMH / WS 982), p. 17

[34] McCartan, Patrick (BMH / WS 766), pp. 63-4

[35] Irish Times, 07/05/1917

[36] Ibid, 08/05/1917

[37] Irish Independent, 08/05/1917

[38] Ibid, 09/05/1917

[39] Ibid, 10/05/1917

[40] Meleady, p. 267

[41] Ibid, p. 271

[42] Ibid, pp. 271-2

[43] McCormack, Michael (BMH / WS 1503), p. 9 ; Nugent, p. 100

[44] Irish Times, 09/05/1917

[45] MacCarthy, p. 14

[46] Ibid, p. 15

[47] O’Shiel, pp. 42-3

[48] MacCarthy, p. 15

[49] Wyse-Power, Charles (BMH / WS 420), p. 14

[50] O’Shiel, p. 43

[51] MacCarthy, p. 15

[52] Irish Times, 11/10/1917 ‘ O’Shiel, p. 44

[53] MacCarthy, pp. 13-4

[54] Longford Leader, 12/05/1917

[55] Good, Joseph (BMH / WS 388), p. 31

[56] Doherty, p. 5

[57] Irish Times, 11/10/1917

[58] Shouldice, John (BMH / WS 679), p. 13

[59] Irish Times, 11/05/1917

Bibliography

Newspapers

Irish Independent

Irish Times

Longford Leader

Roscommon Herald

Book

Meleady, Dermot (ed.) John Redmond: Selected Letters and Memoranda, 1880-1918 (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Doherty, Bryan, WS 1292

Ginnell, Alice, WS 982

Good, Joseph, WS 388

MacCarthy, Dan, WS 722

McCartan, Patrick, WS 766

McCormack, Michal, WS 1503

Nugent, Laurence, WS 907

O’Brien, William, WS 1766

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

Shouldice, John, WS 679

Wyse-Power, Charles, WS 420