A continuation from: Rebel Runaway: Liam Mellows in the Aftermath of the Easter Rising, 1916 (Part III)

Finally in America

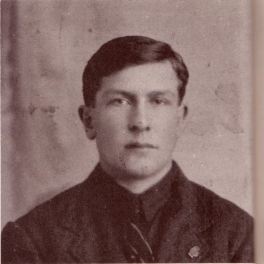

Safe in New York, if unsettled, Patrick Callanan pined for his friend and former commanding officer, Liam Mellows. Other Irishmen had joined him in the United States, also fleeing in the wake of the failed Easter Rising, but Mellows was not amongst them.

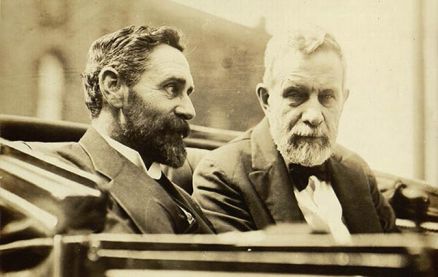

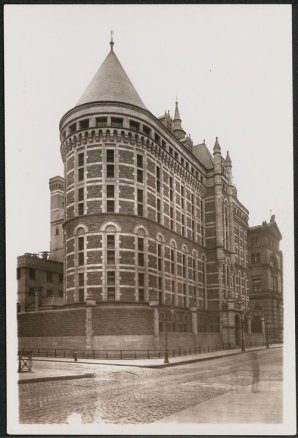

Callanan had discussed him with John Devoy when he visited the offices of the Gaelic American newspaper – of which Devoy was editor – after coming to New York in November 1916. Callanan reassured Devoy, a Fenian old-timer and one of the most powerful men in the Irish-American community, that Mellows was on his way. And yet, with no further word, Callanan could not help but worry.

His own journey had been an arduous one. After the disbandment of the Galway Volunteers at Limepark House on Mellows’ reluctant orders, Callanan was among those forced to go on the run. He first hid out with his cousins in Co. Galway, before moving to Co. Clare and then Waterford town, from where he took a boat to Liverpool, and then another to Philadelphia.

The Atlantic crossing took nineteen days, at risk all the while from German submarines. When nearing the mouth of the Delaware River, the crew was told to extinguish all lights lest they betray their position to any lurking U-boats. After disembarking safely, Callanan pushed on to New York, where Devoy and the Irish-American organisation he headed, Clan na Gael, welcomed him with open arms as a fellow revolutionary.

Provided with some money by Devoy for living expenses. Callanan could at least take a well-earned. But waiting idly did not suit him, nor did it for many of his compatriots in the city, and the initiative was made – without consulting Devoy – to contact the German ambassador, Count Johann von Bernstorff.

Following some consultation with Berlin, Bernstorff was able to report back the willingness of his government to land arms and soldiers on the west coast of Ireland. Considering the lacklustre support Germany had granted to the previous uprising earlier in the year, this was a questionable claim, but Callanan took it at face value.

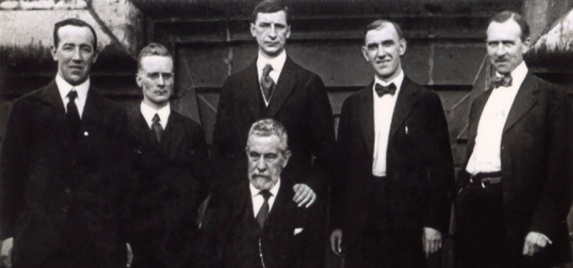

Callanan was abed one night in December 1916 when he was woken by someone pulling at him. To his surprise and joy, it was none other than Mellows. The two comrades-in-arms had not seen each other since leaving Limepark House, eight months ago. After sleeping the rest of the morning in bed together, Callanan took him to the Gaelic American office and introduced him to Devoy, who was quite taken with the newcomer, praising him as the most capable man who had yet arrived (Callanan did not seem offended by this), and going so far as to offer him a job on his newspaper.

Devoy would not be quite so amiable when learning of the contacts made with Count von Bernstorff. The émigrés had gone behind his back, on his territory of New York no less, and Devoy was fiercely intolerant of anything that encroached on his prerogatives. His anger was a sign that life in America for the Irish exiles would not necessarily be an easy, nor a straightforward, one.[1]

The War Continues

Callanan let Mellows in on the arrangement for Germany to supply arms and men to Ireland. Having been let down before by their ‘gallant allies in Europe’, Mellows thought it best to proceed with care by first sending a man to Germany and another two to Ireland to ensure the whole process went smoothly. Callanan went along with Mellows’ amendments to the plan without a murmur. After examining some maps together, they agreed that the Martello Tower near Kinvara, Co. Galway, would make the best landing site.[2]

It would be but another move in the fight for Irish freedom, which had been paused but never ceased as far as Mellows was concerned. He was especially keen to correct all talk to the contrary, as Callanan described:

At this time rumours were current in America that there would be no more fighting in Ireland and that all we wanted was to be represented at the Peace Conference [when the First World War was over]. Mellows resented this very much and he stated at several meetings that Ireland would fight again, and what we wanted was arms.[3]

Even when Callanan moved to Boston, the two men remained in contact. One Saturday – the day he usually visited New York to see Mellows – Callanan found his friend in an especially serious mood.

Mellows told him that he had been in communication with a German woman living on the West Coast. She was willing to offer a boat of hers at their disposal if a crew could be provided. For this, Mellows tasked Callanan with finding four or five others to serve as firemen and coal-passers, while he would inquire after engineers.

The plan was for Mellows to lead the others in sailing through Russian waters to Germany, taking the lengthier westwards route rather than the more direct Atlantic one to avoid the British navy. In Germany, the boat would be loaded with munitions and then landed in Ireland, as previously discussed.

Fired up, Callanan agreed to do his part and succeeded in recruiting four sailors-to-be, but when the pair met again on the following Saturday, Mellows admitted to being unable to muster enough engineers. The plan was cancelled and, while it would not be the only arms-running attempt, it was but the first of many setbacks Mellows faced in the Land of the Free.[4]

A Great Spirit

In the meantime, there were other ways to further the cause. To his delight, Callanan found that in the States “a great spirit prevailed at this time, especially among those of Irish descent. They were all very anxious to hear about the happenings of Easter Week.”[5]

It was a zeitgeist Clan na Gael was keen to tap into it, and Mellows spoke on behalf of the society at a series of meetings. As one of the participants in the Rising, and a leading one at that, Mellows made for an especially effective speaker, holding his audiences spellbound with his tales of the heroics from that fateful week.

His oratory, remembered one witness, Robert Briscoe, “made you see things he had experienced, and dream the same great dreams.” Though the revolution had been bloodied, Mellows assured his listeners, it had not been broken. It lived on, seething beneath the seemingly pacified surface of the country. This was music to Briscoe’s ears. The vision Mellows invoked “struck deep into my soul, bludgeoning my common sense.”

Since landing in the United States from Dublin in December 1914, Briscoe had lived the life of a Horatio Alger hero, earning his first dollar as a humble packer before partnering in a lucrative company that produced Christmas tree-lights. But the American dream proved not enough, as Briscoe found his thoughts returning to his homeland, piqued in particular by the news of Easter Week.

Hearing Mellows speak confirmed to Briscoe what he had to do. Turning his back on his thriving business, he took on the duties of shipping guns to Ireland. In time, he would become a close friend of the man who had made him a convert.[6]

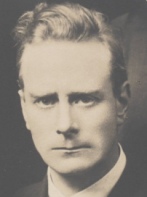

Frank Robbins

While Mellows was helping to clear the doubts of others, he was having some of his own. “If I had known as much in Easter Week as I know today I would never have fired a shot,” he told Frank Robbins as they were walking together in New York in mid-1917.[7]

Like Mellows, Robbins had fought in the Rising, except in his case he had been a sergeant in the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), in charge of occupying the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin. Released from Frognoch Camp in August 1916, his defiance, like that of Mellows’, remained undimmed as he assisted in the ICA revival, or at least tried to, as it lacked the necessary funds and contacts to make much of an impact anymore.

But Robbins did not allow himself to despair. When asked by Tom Foran, the General President of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), to head Stateside and connect with the Union’s erstwhile leader, Jim Larkin, Robbins readily accepted.[8]

Reaching New York in late 1916, Robbins made the acquaintance of many in the radical Irish-American scene, including Devoy and Mellows, the latter he came in contact with through a mutual friend, Nora Connolly, daughter of the Easter Week martyr, James Connolly. Both Robbins and Mellows had been close to her father, but they had not met until Nora passed on Mellows’ address at 73 West 96th Street, where he was staying with the Kirwan family.

Robbins was thrilled to meet a man who had been so influential in revolutionary circles back in Ireland, and who continued being so in New York, recognised by all, according to Robbins, as the de facto leader of the ‘1916 exiles’. The appreciation was reciprocated, with Mellows giving Robbins a copy he had signed of John Mitchel’s classic Jail Journal.[9]

Doubts and Uncertainties

And so it was with some surprise that Robbins heard Mellows express such bitter incertitude. Only the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) had the authority to declare an uprising, Mellows said, and that had been appropriated. To Robbins’ astonishment, Mellows castigated those responsible as a junta which had ignored everyone else in its pursuit of its own intrigues.

Robbins thought this change of heart was due to what certain other Irish émigrés had been saying, but Mellows adamantly denied this to be the case. Robbins then methodically dissected Mellows’ volte-face.

He had been singing the praises of the Rising, while eulogising James Connolly, Tom Clarke, Patrick Pearse and all the others who had laid down their lives to rejuvenate Ireland’s soul, bringing the cause of national freedom to the world stage, and saving its manhood from British servitude. With all that said, if Mellows now believed the opposite, he should go back before the people of America and tell them so.

“But before you do that, I would ask you to examine the whole matter thoroughly,” Robbins continued. For if Mellows was still uncertain, he would have to give the benefit of the doubt to those who had made the ultimate sacrifice and whose efforts, Mellows had to agree, were now bearing the fruits the two of them were looking forward to gathering.

“Thanks, Frank,” Mellows replied, “I never looked at it that way. You have eased my mind considerably. I was very worried about the whole matter.”[10]

Another disagreement was when Mellows posed the question as to what form of government a free Ireland should take. As Robbins was a staunch republican, and knew Mellows to be the same, he assumed his friend was jesting in his contention that the people should be free to choose, whether it be a republic or monarchy, but the conversation grew heated as Mellows refused to back down.

“He continued to uphold the view that it was for the people to decide,” Robbins wrote years later, still in shocked wonder. He assumed that Mellows “had not expected opposition from me but having taken the stand he would not retreat. So the talk ended in disagreement,” and not for the last time.[11]

By a quirk of fate, Mellows would end up opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty as an unacceptable compromise, while Robbins, who had denounced anything short of a Republic, accepted the agreement for something that fell short of that ideal. But such contradictions and tragedies were to be for the future.

The Search for Guns

Mellows came to trust Robbins enough to bring him in on his latest German gun-running mission. The version he had arranged with Callanan had been elaborated into three separate landings in Co. Wexford, Down and Clare. In preparation for this, Mellows was to work on a fruit-boat from New York to Montevideo, and from there take another to Spain, where a submarine would pick him up for the final leg of the journey to Germany. Thinking he was looking for assistance, Robbins volunteered his services, but Mellows at first demurred.

‘Our friends down town’, by which Mellows meant Clan na Gael, had ruled this to be a one-man job. Robbins was a little mystified at this, and wondered if Mellows had simply failed to be assertive: “It was not for me to make a comment but I thought that had Mellows pressed the need for a second it would have been conceded.”

Regardless, it was agreed between the pair that Robbins would play a part after all, by searching around the docks for some helping hands. He believed he was aiding his friend by covering for his personal deficiencies:

He was not very conversant with dockside life…In many ways I found him to be a bit of an introvert which made it very difficult for him to mix with the many different kinds of men one meets in sailors’ haunts.

(Which – considering Mellows’ past success with making friends in Fianna Éireann and the IRB, and then the Irish Volunteers, to say nothing of his exploits in escaping from England in time for the Rising, and the subsequent flight to America, the latter which saw him surviving the toils of working life on board a ship – seems an unfair statement on Robbins’ part.)

One point of contention was Mellows’ insistence on total secrecy, which was all well and good – until he cited Jim Larkin in particular as someone to keep in the dark. Offended, Robbins asked if this was due to Larkin being a socialist because, if so, Mellows could rule him out as well for he too was one.

A distraught Mellows insisted this was not so, arguing that while he knew naught about socialism, he also had nothing against it, having read James Connolly’s Labour in Irish History and finding it much to his liking. When Robbins pressed for a reason, Mellows refused to say, only that he would divulge at a later time – which he never did.

With this disagreement pushed to the side, the two men got down to business. Robbins was to remain in New York until he received word that Mellows was en route to Spain, at which point he would return to Ireland and alert their fellow revolutionaries to the incoming weapons.

“However, the arms plan never came to anything,” Robbins admitted.[12]

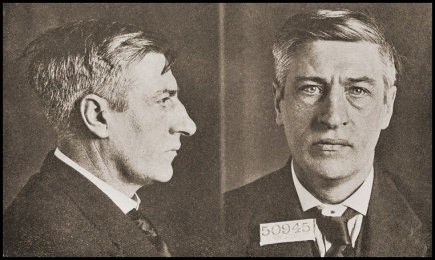

John Devoy

Robbins later found a reason for Larkin being persona non grata to Clan na Gael: the temperamental ‘Lion of Labour’ had delivered a tongue-lashing to Devoy in the Gaelic American office, accusing him of snobbery in favouring the Irish Volunteers with money while ignoring the more working-class ICA members in America. Larkin may have ruled the ITGWU with an iron fist, but he was not in Ireland anymore and, in Devoy, he met his match as an autocrat.[13]

Not that Robbins spared the curmudgeon much sympathy. Although he had been sent to contact Larkin, Robbins was soon disgusted with his bilious rants and found himself much preferring the company of Devoy. He was amazed at the older man’s intelligence and how “he could foresee developments well in advance of most writers.” Devoy’s austere dedication also impressed Robbins. Instead of the money and fame that Robbins believed Devoy could have earned, he:

…preferred to travel a lonely, torturous and unpopular path for the meagre salary of twenty-five dollars per week, which he regarded as being sufficient to take care of his very simple way of life. His only regard was the advancement and, if possible, the achievement of the freedom of Ireland, and be counted as one who had given service to that cause throughout his whole life.[14]

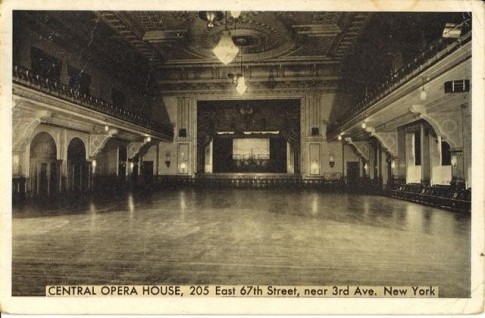

Robbins was a witness to the extent of Devoy’s influence at a packed Clan na Gael convention in the Central Opera House. After a succession of stirring speeches about the historical fight for Irish freedom had put the audience in the appropriate mood, Devoy implored them for funds with which to carry on that same mission.

This prompted a number of delegates to leap to their feet and compete for the stage to proudly announce the amounts they personally, and the Clan clubs they represented, would be donating.

“They were almost shouting each other down in their anxiety to be heard,” wrote Robbins, awed by the memory.[15]

Others were less impressed by the grizzled Fenian. Sidney Czira (née Gifford, sister-in-law to Joseph Plunkett) complained that Devoy tried to separate the ‘1916 exiles’ into different states. The purported reason was to lessen the risk of police surveillance, which Czira conceded was a concern. But she attributed this policy of Devoy’s less to safety and more to his suspicions.

Others were less impressed by the grizzled Fenian. Sidney Czira (née Gifford, sister-in-law to Joseph Plunkett) complained that Devoy tried to separate the ‘1916 exiles’ into different states. The purported reason was to lessen the risk of police surveillance, which Czira conceded was a concern. But she attributed this policy of Devoy’s less to safety and more to his suspicions.

“He had this extraordinary obsession that there was somebody always interfering or intriguing against him,” she wrote with a sigh.[16]

But, of course, even paranoiacs have enemies. One of whom in Devoy’s case would just happen to be Czira.

Sidney Czira

About March or April 1917, Robbins received a written invitation to Czira’s apartment in Amsterdam Avenue. When he arrived, he found Mellows and other ‘1916 exiles’ also there. Czira explained the purpose of the meeting: she wanted to replace Clan na Gael, whose leadership she believed was out of touch with the struggle back in Ireland, with a new fraternity, the nucleus of which would be the ‘1916 exiles’.

After some discussion, the guests made their way out. Mellows asked Robbins what he thought. Robbins was blunt: what was the point of undermining their number one patron in a country they knew little about? The only thing this could accomplish was the hurting of their own cause.

Mellows agreed – at least, on the surface. Robbins thought that was the end of the matter – until a new organisation did indeed come into being, the Irish Progressive League.[17]

At its forefront was Czira, who threw herself into the fray of activism, as she described:

We set up a shop, the front part of which was devoted to Irish books, pamphlets, periodicals, postcards, badges and the usual propaganda material. This must have been 1918 because we had in the window a map which we used in the way that war maps were used at this time, by sticking pins with little flags to indicate the constituencies in which Sinn Féin were victorious in the election.[18]

As if this was not enough, Mellows set up a society of his own sometime later, the Irish Citizen’s Association, intended for use as a pressure group on Clan na Gael. Such behaviour would forever be a puzzle to Robbins: “In later years I often asked myself if Liam Mellows was partial to the first project and founder of another. Or was he under the influence of someone else?”

It was inexplicable to Robbins that his friend could act this way after they had agreed on the foolishness of such maverick ventures. Perhaps the answer, Robbins speculated gloomily, lay within their national psyche: “Sometimes I think the Irish have an inbuilt genius for disagreement and disunity.”[19]

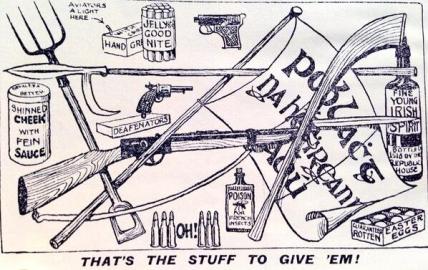

Clan na Gael

If the Rising of 1916 had ‘changed, changed utterly’ Ireland, in the words of W.B. Yeats, then the entry of the United States into the Great War in April 1917 – on the side of Britain, no less – had a similar effect on Irish-America. Outspokenly pro-German before, Clan na Gael was forced to ask itself if keeping to its stance was worth the hostility from the rest of the country, now on the lookout for unpatriotic malcontents within. The answer, as far as Devoy and the rest of the Clan old-guard were concerned, was ‘no’.

Others like Mellows vehemently disagreed. To those who had risked life and liberty in Dublin’s streets or the fields of Galway during Easter Week, suggestions that they now enrol in the American army and fight alongside the same enemy as before were intolerable.

This clash between pragmatism and principles – not the last in Mellows’ life – soon boiled over into public view, such as when a Clan convention on Easter 1917, for the first anniversary of the Rising, was disrupted by audience members loudly objecting when the platform speakers urged them to enlist. So stormy was the mood that hall stewards ordered the protestors to remove their tricolour badges, which was refused.

This clash between pragmatism and principles – not the last in Mellows’ life – soon boiled over into public view, such as when a Clan convention on Easter 1917, for the first anniversary of the Rising, was disrupted by audience members loudly objecting when the platform speakers urged them to enlist. So stormy was the mood that hall stewards ordered the protestors to remove their tricolour badges, which was refused.

Though Czira was not present, being at home with her two-month old baby, she heard much about it when many who were disgruntled at the stance the Clan was taking visited her apartment to discuss what should be done. Of particular concern was the agreement between the American and British authorities that the former could conscript British nationals, among which the Irish who were not American citizens had been classified.

In a series of open-air meetings protesting against enlistment, Mellows took the lead, mixing impassioned oratory with cutting humour. With reference to the poster ‘What did you do in the Great War, Daddy?’ that was plastered about the city, Mellows suggested that an answer should be: “I was tracking around New York the Irish who were trying to obtain their liberty.”

Displeased at this unseemly independence, the Clan na Gael Executive gave Mellows a stark choice: speak no more at such meetings or forget about his Gaelic American job. The man who had disbanded the Galway Volunteers in the face of a hopeless situation only with great reluctance was not going to back down now, and the Clan soon learnt about the sort of enemy its former golden boy could be.

Displeased at this unseemly independence, the Clan na Gael Executive gave Mellows a stark choice: speak no more at such meetings or forget about his Gaelic American job. The man who had disbanded the Galway Volunteers in the face of a hopeless situation only with great reluctance was not going to back down now, and the Clan soon learnt about the sort of enemy its former golden boy could be.

When the first day of a Clan gathering in New York in 1918 passed without any speakers making reference to the ‘German Plot’ – over which a number of arrests had been made in Ireland on allegations of German collusion – there was considerable outrage in the hall. That none of the ‘1916 exiles’ were among those on stage was another cause for resentment.

The second day of the convention came and still not a word was said about the arrests, leading to shouts for Mellows, who was on the premises, to be allowed to speak. Taken to a backroom, Mellows – as he told Czira afterwards – was accused by the Clan bigwigs of being behind the upheaval, which he denied.

As a small compromise, and in the hope of diffusing the tension, Mellows would be allowed on the platform to bow before the audience, but on no condition was he to speak. Of course, as soon as he was on stage, he denounced the arrests and, for added effect, proposed a resolution of protest.

“American papers on the following day commented that although the proceedings were very dull on the first day, they were certainly very lively on the second,” Czira commented dryly.[20]

John Devoy

At least relations between Mellows and Devoy remained cordial, if lacking the same warmth as before. “I fear for the Irish movement in America when the Old Man dies,” Mellows told Robbins in the belief that there was no one who could fill Devoy’s shoes. It was a sentiment he would repeat on numerous occasions, according to Robbins.

Similarly, Devoy continued to hold Mellows in high regard, however personally he took their widening estrangement. A rumour that he had financially neglected Mellows to the point of starvation wounded him, as did the other man’s silence on the issue, which was taken by many to mean an affirmation.

“You know how much I loved Mellows,” he said to Robbins, who had managed to stay on good terms with both. “I loved him as if he had been my own son.”

He said this in the Shelbourne Hotel during his visit to Dublin in 1924. Mellows had been dead for almost two years, put before a firing-squad of his fellow countrymen, but the memory of his failure – or refusal – to dispel the whispers of ill-treatment lingered on as a knife in the old man’s gut.[21]

Mellows caught something of the complexity of their relationship in a letter to Nora Connolly, dated to September 1919:

I broke completely with the Gang. Lots of things happened – more than I can write about and more than was known even among friends. Threatened with expulsion from everything. Told them to do it. They backed down. Resigned from the office at the same time. Was begged to remain by Uncle. Did so.

That Devoy was ‘Uncle’ was telling in the familial choice of word. Despite Mellows agreeing to remain with the Gaelic American, he complained of a “campaign of the most vile and conscious slander” against him.[22]

This toing-and-froing, akin to a fraying marriage, could not last indefinitely. Mellows had been staying in the apartment of Patrick Kirwan, the brother of a leading Irish Volunteer in Wexford, where Mellows’ mother hailed from. Upon his first meeting with Mellows, Kirwan was delighted to learn that they knew many of the same people from Wexford.

This toing-and-froing, akin to a fraying marriage, could not last indefinitely. Mellows had been staying in the apartment of Patrick Kirwan, the brother of a leading Irish Volunteer in Wexford, where Mellows’ mother hailed from. Upon his first meeting with Mellows, Kirwan was delighted to learn that they knew many of the same people from Wexford.

The Kirwan home of 73 West 96th Street became a centre for him and his friends. The Kirwans did not seem to mind the constant flow of guests, taking care to make each of them welcome, and Mellows was close enough to the family to stand as godfather to their third son.

Father Magennis

After two years of this cosy arrangement, Mellows abruptly left in mid-1919 without warning. The Kirwans found that he had been moving his books out in batches without telling them until the last day. It was only later that they learnt he had relocated to Manhattan’s East Side, the Carmelite School on East 28th Street, where he was employed as an Irish language teacher, having abandoned the Gaelic American for good.[23]

The head of the monastery, Father Peter Magennis, had long been a source of aid for the ‘1916 exiles’. When Czira found it impossible to send letters back home due to the strict censorship, Magennis delivered her correspondence, and that of many others, while he was over in Ireland.[24]

After Mellows collapsed at his first replacement job as a labourer, it was Magennis who had given him the teaching post, a role more suited to his education. His health, until then in a perilous state, began to mend.[25]

Mellows was, according to Robbins, “subject to spells of despondency and was inclined to neglect himself.” When two female friends learnt of his plight, they visited him in the East Side and succeeded in nursing him back to health. It was for this bleak period that Devoy was blamed for starving him. It was an unjust accusation to Robbins’s mind, and Mellows seemed to allude to this misconception in a story he told Czira.[26]

When he was young and sick in bed, he had overheard the doctor attribute his state to malnutrition. Thinking someone was blaming his mother for not feeding him properly, an enraged Mellows tried to rise out of bed and attack the doctor. Still, as Devoy bemoaned to Robbins, Mellows made no effort to correct the impression.[27]

Patrick McCartan

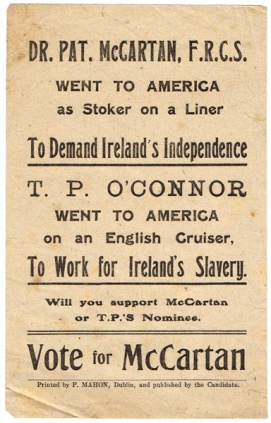

Mellows was still on amiable terms with Devoy when, in mid-1917, Dr Patrick McCartan came to New York and – in keeping with the new tradition for Irish revolutionaries on arrival – visited the Gaelic American offices. Robbins were there with Devoy when Mellows introduced him to the newcomer.[28]

Much like Mellows and Robbins, the thirty-eight year old McCartan had already had a colourful career as an Irish freedom fighter. He had spent time before in America, working as a barman in Philadelphia, where he made the acquaintance of Joseph McGarrity, the leading Clan official in the city.

By 1905, McCartan had returned to Ireland, buoyed by a loan from McGarrity to pursue a medical career, and also to encourage a growth of radical politics in his native Tyrone, a task he fulfilled with enough vigour to be ‘honoured’ in a police report with the accolade of being “the most dangerous man in the county.”

But he was evidently not dangerous enough for some. Despite joining the IRB Supreme Council in July 1915, McCartan was among those side-lined in the planning of the Easter Rising. When the big event came, McCartan was as lost as anyone, and ended Tyrone’s involvement by sending its Volunteers home unbloodied.[29]

After disappearing from the county for some months, McCartan re-emerged in Tyrone at the end of 1916 and was arrested in February 1917, being deported to England along with a number of others. Three months later, he came back to Ireland in time to campaign for Sinn Féin in the South Longford by-election.

“Nothing further was known of his movements until it was announced that he had arrived in America, where he had succeeded in reaching by working his passage as an ordinary seaman,” reported the Irish Times.[30]

Before McCartan had left Ireland, it was decided by the IRB leadership that he would join Mellows on his much-anticipated mission to Germany. Mellows was to handle the purchase of arms while McCartan tended to the political aspect. The duo were allocated some leeway in their plans, depending on circumstances, as McCartan put it:

Mellows and I were left free to do what we thought best on reaching Germany but one or both of us was to accompany the war material, to the arranged spot, on a fixed date. If we could get more than one consignment, either of us was to remain behind to escort the second cargo. Mellows and I were delighted with this plan, for which the Clan undertook to make the arrangements.[31]

There was just one snag: McCartan was an idiot.

Lost and Found

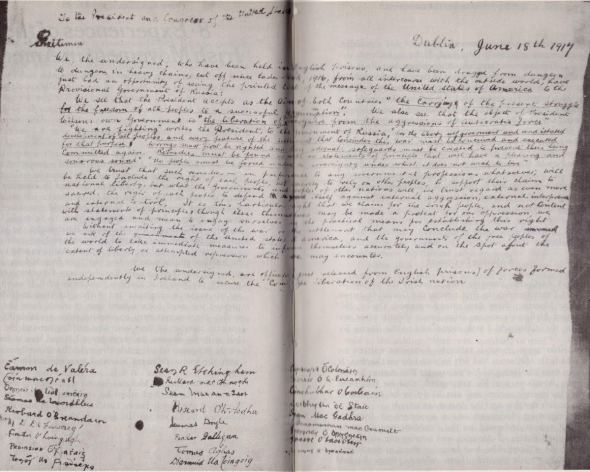

While he talked with the other three in the Gaelic American offices, the subject arose of a certain document that McCartan had left behind on the ship that had brought him over three days earlier. It was a linen document, making a case for Irish independence, addressed to the US President and to Congress, and bearing the signatures of twenty-six individuals from the 1916 Rising. The linen had been specially prepared and starched so that the words could be written in indelible ink, before washed back into a pliable state and then sewn into the lining of McCartan’s waistcoat.

It seemed the perfect cover – until McCartan feared he would be searched on entry to New York. So he left the document on board.

Quite what he had intended to do then was unclear, as was the importance of the document, for during the conversation with the other three, McCartan could not make up his mind on whether it was worth retrieving. Exasperated, Robbins:

…drew Mellows aside and asked him to find out from the doctor if, in fact, the document was important. If it was I undertook to try and obtain it from aboad ship.

When Mellows asked how he intended to do this, Robbins said he would bluff his way through by pretending to be looking for a job. McCartan looked relieved at this plan of action, and so he, Mellows and Robbins left Devoy and went to the West Side where the ships were berthed. Deciding that fortune favours the bold, Robbins pressed ahead:

At the entrance to the docks I walked very smartly in without taking any notice of the guard. As I walked on I heard a voice shout “Halt” but paid no attention. Next there was a rush of feet, a few swear words and I was asked did I want a so-and-so bayonet into me.

Robbins did not. All wide-eyed innocence, he turned to the furious guard, who demanded to see his pass. Robbins tried feigning ignorance as to why a humble job-seeker like him would need such a thing, but when that made no headway with the other man, he spun a sympathy story about how he had missed his ship out due to drink and was in desperate need of another job.

Moved by this tale of woe, but not enough to give way, the watchman asked Robbins if he knew the bosun and, if so, whether he could vouch for him. Robbins confidently said he did but, when the guard left to find the bosun, he knew that the jig was up and retreated to where Mellows and McCartan were waiting.

That was not the end of the missing document, for it finally appeared in the possession of Joseph McGarrity. McCartan had visited his old friend in Philadelphia immediately after landing in New York, during which he might have handed the document to him. If so, that was a severe breach of protocol, given that Devoy was the point-man in America for the IRB.

Still, Robbins was not entirely convinced by this explanation:

Having been present at the discussions…with Devoy, Mellows and himself, I formed the opinion that McCartan was genuinely concerned about leaving the document on the ship, and that it was afterwards rescued by contacts made by Devoy.

Another version of how Devoy retrieved the item was by demanding it in person from McGarrity, who instantly surrendered it. When Clan na Gael ruptured into hostile factions, McGaritty and McCartan would side with the anti-Devoy camp, suggesting that it was not coincidental that McCartan gave the presidential letter to McGarrity over Devoy. If so, then Devoy was being far from unreasonable in seeing plots against his authority.

As for the declaration, it was eventually given to President Wilson, though not on the original linen.

“Frank, McCartan would never make a good revolutionary and do you know why?” Devoy asked Robbins one day in the office. When his companion replied he did not, Devoy explained: “Because he can never make up his mind and I attribute that weakness to the fact that he smokes too many cigarettes.”[32]

Robbins took a similarly dim view of the newcomer, albeit for reasons other than a penchant for tobacco, believing him to be a bad influence on Mellows. When Mellows shocked Robbins by questioning the rightness of the Easter Rising, and his accusations that the IRB Supreme Council had been usurped, Robbins heard the echo of McCartan’s words in Mellows’, and blamed the Tyrone native for filling his friend’s head with such doubts.[33]

In time, Mellows would be similarly unimpressed with McCartan and his unreliability. McCartan “was the only man I could say that Mellows was even bitter against,” recalled Peadar O’Donnell.[34]

Beekman Place

For the moment, however, Mellows and McCartan worked closely together, with both becoming regular visitors to Czira’s apartment at Beekman Place. When she happened to mention that a German friend of hers, Lucie Haslau, had told her that she had seen off some members of the German embassy, whose time in America were over due to the wartime severance of diplomatic relations, McCartan was surprised. He had been told by Devoy that there were no ships leaving the States.

The next morning, McCartan returned with Mellows in tow. Mellows asked Czira if her German friend knew whether it would be possible for them to take the same route out. That Mellows had come at an unusually early hour indicates how excited – and impatient – he was.

(Mellows kept a loose schedule in general, to the point of being a night-owl. He would think nothing of dropping by Beekman Place, regardless of the hour. Czira remembered how on one occasion Mellows was leaving in the morning and bade the milkman ‘Goodnight’.)

When Czira returned with Haslau’s answer in the affirmative, Mellows and McCartan asked to be put in touch with her, which Czira did. She urged them not to tell any of the Clan elders like Devoy, but McCartan replied it would not be fair to keep the ‘Old Man’ in the dark.

She also questioned the involvement of a Dr von Recklinghausen, a friend of Haslau’s, who handled German propaganda in the States. Czira urged Mellows against bringing him to their gatherings at her apartment, fearing the German was too obvious a target for police surveillance, but he assured her he would be careful not to be seen in von Recklinghausen’s company. She was further alarmed when Mellows took to meeting von Recklinghausen in Haslau’s flat at the other end of the terrace from hers.[35]

For once, she and Devoy were in complete agreement. He warned McCartan that Haslau’s house was under constant watch by the authorities, but the conspirators continued to meet there regardless. Given that Devoy had already been proved wrong about the lack of ships leaving America, there seemed little reason to heed his caution.[36]

Setting in Motion

When Callanan answered Mellows’ summons to see him in New York after Sunday Mass, he found him with several others, including Robbins. Mellows, he noted, appeared distraught. When asked the reason, Mellows, pent-up for too long, laid his cards on the table.

Clan na Gael could no longer be relied on, he said, with the exception of a few allies such as McGarrity in Philadelphia. With no further hope of smuggling arms from America, they were wasting their time here. The only thing left to do was for them to go back to Ireland, while Mellows intended to reach Germany to find aid there.

Callanan and another man present, Donal O’Hannigan, agreed to return home as soon as possible. Meeting Callanan later in the week, Mellows told him that he had a good chance of making it to Germany via a Belgian relief ship that was waiting by the docks. From Belgium, Mellows explained, he could go to Holland and then onwards to his destination.[37]

Mellows explained this plan to Devoy, with McCartan and O’Hannigan present, in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. That he did so showed that relations between him and Devoy had not yet completely broken down. Indeed, the old Fenian had been busy on Mellows’ behalf, cabling Germany to obtain the password – the not overly imaginative ‘Berlin’ – the others were to use when communicating with German intelligence. When Mellows, McCartan and O’Hannigan were leaving the hotel together, they noticed four men shadowing them, whom they assumed were police agents.[38]

O’Hannigan and Callanan were able to obtain their seamen’s papers without much fuss. The same could not be said for Mellows and McCartan, thanks to the latter’s chronic incompetence.

When the pair went to the Shipping Board, as Mellows related to Robbins, they were questioned about the previous vessels on which they had worked. Which was only to be expected, this being standard practice, but McCartan managed to give the wrong name of his supposed last ship, answering instead with what his seaman’s book said was his second last. He also guessed incorrectly when asked if he had worked as a seaman or a fireman.

The official excused himself for a couple of minutes. When he returned, he stamped their books as being in order. All seemed as it should – except that from then on, Mellows was to complain about a feeling of being constantly monitored. His watchers were less than subtle, such as when the letter box for the Kirwans’ flat – where Mellows was then still living – was broken apart and the opened letters discarded in the hallway, or the stove added to the street corner across from the Kirwans’ apartment to keep the policemen waiting there warm at night.[39]

Entombed

Czira was surprised when Mellows failed to arrive one evening as he usually did. The next day, with rumours swirling of Mellows’ arrest, she was visited by another of the exiles, a Tipperary man called Michael O’Callaghan. Usually so cheerful, O’Callaghan merely sat there in gloomy silence.

Knowing his volatile reputation – O’Callaghan had fled Ireland after shooting two policeman dead – Czira was afraid to ask anything about Mellows. When O’Callaghan finally left for the night, it was much to her relief. He was arrested almost immediately after, as Czira heard:

He was followed by an American detective and was growing more and more irritated as he walked through the streets, wondering over the fate of Mellows, he suddenly saw in front of him in a shop window a large picture of John Mitchel, grandson of the patriot, who was then running for Mayor of New York and who was an out and out Britisher. (I think there was some pro-British sentiment on the poster.)

This was the last straw as far as O’Callaghan was concerned, and he went up and smashed the window. He was promptly arrested.

When Czira went to Haslau’s flat, she was told by her German friend that she had heard nothing about von Recklinghausen since he and Mellows departed from her house together in the early hours. Haslau then telephoned von Recklinghausen’s apartment, only to be curtly informed by the landlady that not only was he not there, he was not expected back anytime soon.

For he and Mellows had been detained together after leaving Haslau. McCartan was picked up later by the Canadian authorities in Halifax where he was waiting for his outbound ship to be repaired.[40]

While visiting Mellows in Tombs Prison, Robbins was shocked at the noise and confusion. He was led by a warden along a line of half-open cages, to the one where Mellows was waiting with something urgent to say. At first they tried talking in Irish but the din, combined with Robbins’ imperfect grasp of the language, meant that the two men had to switch to English. Even then, the pair had to shout at each other over the babel of voices to understand the little they could.

Robbins left Tombs rather shaken: “It certainly was an experience never to be forgotten.”

Beforehand, while on his way to the prison, Robbins had broken the news of the arrests to Mellows’ friends, such as Nora Connolly, as well as stopping by the Gaelic American offices. Devoy was out of town, so Robbins left a message for him. He did not think anything in particular of Devoy’s absence.

Connolly and another friend, Margaret Skinner, saw Mellows in Tombs later that day and, being more fluent in Irish than Robbins, they were able to discern what Mellows wanted them to know. They then went to the Kirwan house and found behind a picture in the dining-room some papers that the detectives had missed in their search.[41]

‘A Sinn Fein Rebellion’

Nonetheless, the authorities were able to secure a significant cache of paperwork, according to the Irish Times:

A considerable amount of literature and papers, interesting to the American Government, were taken in the raid on Mellowes’s [alternative spelling] and Von Recklinghausen’s premises, but it will be some time before the ramifications of the plot can be thoroughly exposed.

Nonetheless, it was speculated by the New York Times “that the arrests of Mellows and Von Recklinghausen have frustrated a Sinn Fein rebellion, which was planned for next Easter, on the anniversary of the Dublin rebellion.” Whether or not Mellows and his colleagues had had anything quite as ambitious as that in mind is debatable, though the possibility must have been a tempting one.

Also noted was how:

Recklinghausen had been mentioned as an envoy whom Count Bernstorff left here. He is also associated with a group of Turks.[42]

Which made sense, given how Turkey was allied to Germany. According to Czira, however, this supposed Turkish connection came due to a misunderstanding, as a vice-consul for Turkey was living in the flat above her. This entirely innocent diplomat “had made a very bad calculation when he moved into Beehan Place, thinking this was a nice quiet spot!”

Czira, meanwhile, was doing her best, along with Connolly, to help their imprisoned friend. Connolly approached some of the leading Clan na Gael members for help with the bail money, only to be refused. When the two women tried Barney Murphy, the owner of a successful saloon, he listened sympathetically. He was willing to help, he said to them, though he would first have to discuss it with others.

After a couple of days we read in the New York papers that at last somebody put up bail and there was a slightly sarcastic reference to the delay and the unknown person who had come forward.

Murphy, the ‘unknown person’ in question, later told Czira that when he had talked with Judge Daniel Cohalan, a prominent Irish-American politician who was close to Devoy, Cohalan warned him not to get mixed up in ‘this German plot’. Nonetheless, Murphy went ahead and put up the bail money for both Mellows and McCartan, taking care to keep his involvement a secret.[43]

‘Hard, Wretched Days’

Mellows’ case lingered on in legal limbo. Every time he appeared in court, his bail was continued and the case adjourned. With no end in sight by early 1918, Robbins theorised to him that proceedings were being deliberately prolonged by the American Government until the end of the European War, so that it would avoid having to either imprison or deport him, and risk angering its Irish citizens.[44]

The strain wore on his nerves. America was becoming for him a “mild form of purgatory,” he confessed to a friend in August 1918. The plight of Catherine Davis, “a poor Galway woman”, could easily apply to him. He had met her in a New York hospital at her request. Suffering from a heart ailment, she was desperate to hear about her homeland, and her one desire, as Mellows recounted in a letter in January 1919, was to die there. “Her delight was obvious when I answered her salutation in Irish and told her I knew her birthplace well.”

Sometime later, when hearing that Davis was on her deathbed:

[I] called at the hospital…Poor soul! Her one earthly wish will never be gratified. Her days, nay, her very hours are numbered. She didn’t recognise me at first, and then, when she did, was unable to speak: [she] simply held my two hands and repeated time after time, “don’t go.” I stayed with her for about an hour and had to tear myself away. She will never see Ireland again and her heart is broken.

It was a miserable tale that countless immigrants, himself included, could relate to all too well: “To eat their hearts out in exile and to die in the land of the stranger with their thoughts on the land of their love.”[45]

The emotional scars were to stay with him. Even after years had passed, with much that had happened, as Mellows and his companions in the Four Courts awaited the assault by their erstwhile comrades, “he spoke of hard, wretched days in the United States,” wrote Ernie O’Malley.[46]

Mellows would stay Stateside until returning to Ireland in mid-1920 to take up his role in the war against Britain. In the meantime, he remained a fixture on the Irish-American scene, however little he liked it. New York had become a “maelstrom of bitterness and perversity,” where “prejudice is rampant – fierce – unbelievable.”[47]

Still, despite his woes, Mellows never entirely lost his impish sense of humour. Michael Collins would tell a story, one which tickled him considerably, of a performance Mellows delivered during Éamon de Valera’s visit to the United States in 1919. At a large fund-raiser, after some words from de Valera, Devoy, McCartan and Harry Boland, Mellows gave a parody of the speakers before him.

“We collected five hundred thousand pounds for the loan in Dublin. We did. Be Jaysus, we did,” Mellows said in imitation of Boland. He then had to escape the enraged others through a fire escape.[48]

To be continued in: Rebel Operative: Liam Mellows Against Britain, Against the Treaty, 1920-2 (Part V)

References

[1] Callanan, Patrick (BMH / WS 405), pp. 2-6

[2] Ibid, pp. 6-7

[3] Ibid, p. 8

[4] Ibid, p. 9

[5] Ibid, p.8

[6] Briscoe, Robert and Hatch, Alden. For the Life of Me (London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1959), p. 44

[7] Robbins. Frank. Under the Starry Plough: Recollections of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: The Academy Press, 1977), p. 173

[8] Ibid, pp. 94-5, 153-4

[9] Ibid, p. 160-1

[10] Ibid, pp. 174-5

[11] Ibid, p. 179

[12] Ibid, pp. 167, 170

[13] Robbins, Frank (BMH / WS 585), p. 125

[14] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, pp. 160, 165

[15] Ibid, p. 161

[16] Czira, Sidney (BMH / WS 909), p. 36

[17] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, pp. 191-2

[18] Czira, p. 40

[19] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 192

[20] Czira, pp. 37-41

[21] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 193

[22] White, Alfred (BMH / WS 1207), p. 16

[23] Robbins, pp.176-7

[24] Czira, pp. 36-7

[25] Ibid, pp. 39-40

[26] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 177

[27] Ibid ; Czira, p. 40

[28] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 170

[29] O’Malley, Ernie (Aiken, Síobhra; Mac Bhloscaidh, Fearghal; Ó Duibhir, Liam; Ó Tuama Diarmuid) The Men Will Talk To Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018), pp. 46-7

[30] Irish Times, 03/11/1917

[31] McCartan, Patrick. With De Valera in America (Dublin: Fitzpatrick Ltd., 1932), p. 16

[32] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, pp. 170-3

[33] Ibid, pp. 174, 193

[34] O’Malley, The Men Will Talk To Me, p. 23

[35] Czira, pp. 41-3

[36] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 180

[37] Callanan, p. 11

[38] O’Hannigan, Donal (BMH / WS 161), pp. 32-3

[39] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 180

[40] Czira, pp. 43-5

[41] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, pp. 180-1

[42] Irish Times, 03/11/1917

[43] Czira, pp. 44-6

[44] Robbins, Under the Starry Plough, p. 181

[45] Nelson, Bruce. Irish Nationalists and the Making of the Irish Race (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 221

[46] O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), p. 116

[47] Nelson, p. 221

[48] Broy, Eamon (BMH / WS 1285), pp. 29-30

Bibliography

Books

Briscoe, Robert and Hatch, Alden. For the Life of Me (London: Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1959)

McCartan, Patrick. With De Valera in America (Dublin: Fitzpatrick Ltd., 1932)

Nelson, Bruce. Irish Nationalists and the Making of the Irish Race (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012)

O’Malley, Ernie (Aiken, Síobhra; Mac Bhloscaidh, Fearghal; Ó Duibhir, Liam; Ó Tuama Diarmuid) The Men Will Talk To Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018)

O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

Robbins, Frank. Under the Starry Plough: Recollections of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: The Academy Press, 1977)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Callanan, Patrick, WS 405

Czira, Sidney, WS 909

Broy, Eamon, WS 1285

O’Hannigan, Donal, WS 161

Robbins, Frank, WS 585

White, Alfred, WS 1207

Newspaper

Irish Times