A Man for all the Seasons

Among the surviving voices from the War of Independence, Séumas Robinson was an unusually loquacious one. While most Statements submitted to the Bureau of Military History (BMH) were content to begin with an overview of pedestrian facts – e.g. family history, early life and influences, any notable relatives – Robinson’s Statement started his with a playfully philosophical burst:

Somewhere deep in the camera (or is it the anti-camera?) of my cerebrum (or is it my cerebellum?), whose loci, by the way, are the frontal lobes of the cranium of this and every other specimen of homo-sapiens – there lurks furtively and nebulously, nevertheless positively, a thing, a something, a conception (deception?), a perception, an inception, that the following agglomeration of reminisces will be “my Last Will and Testament.[1]

As this quirky, almost singsong, opening sentence would suggest, Robinson was more than just another IRA veteran recalling his war stories for posterity and a pension. For one, he was a full-time staff member of the BMH, which would explain his confidence in beginning his Statement on his own terms instead of following the lead of his interviewer and answering from the list of pre-arranged questions.

Robinson had no time for that, what with the amount he had to say, pent-up as it was from the previous thirty years of silence. That the aforementioned agglomeration of reminiscences of his be known and recorded was a matter of utmost importance to him, despite his concern that he was not in a position to do them justice.

The stated reasons for his worry were many: he was no historian. He had been too close to the events to give them a proper overview like an historian should. History had to be full of facts, and facts were half-lies anyway, so what was the use of history in the first place? If Robinson had been present when Henry Ford had declared that history was more or less bunk, he would undoubtedly have nodded in appreciation (however shocked he would have been at the car tycoon’s atheism, given his devout Catholicism).

Robinson’s soliloquy as the prologue to his Statement is a rambling masterpiece of charming self-doubt, gentle self-deprecation and cheerful cynicism at the follies of man in thinking he can know his own past: “Only an angel can record the truth-absolute.”[2]

It is also a complete façade and one that did not take very long to drop. Robinson was to display throughout the rest of his Statement a very definite certainty in the idea of a truth-absolute, in this world as much as the one of angels, as well as a hot-blooded readiness to spring into attack should his place in history be threatened by unscrupulous and uncouth hoaxers.

And why not? His status was not inconsiderate. He had fought at the Easter Rising and helped change the course of Irish history. During the War of Independence, he had been commander of the Third Tipperary Brigade and then second-in-command to the Second Southern Division. In the theatre of politics he had been elected TD for Waterford-Tipperary East in 1920, had argued vigorously in the Dáil debates over the Treaty, against which he would take up arms against in the name of the Republic, and in the years of peace afterwards he was a Fianna Fáil Senator to the Seanad Éireann.

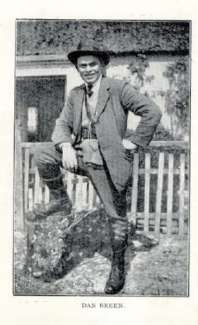

Patriot, guerrilla leader, elected representative, war hero, a historian for all his protests, and finally a statesman – Séumas Robinson had been a man of success in many a field. And yet he was to be constantly tormented, enraged and provoked into writing streams of vehement counter-attacks by the burning conviction that his colleague and brother-in-arms, Dan Breen, the arch-hoaxer, had, with the connivance of the cold-hearted and ungrateful people of Tipperary, fucked him over.

Kathleen Kincaid

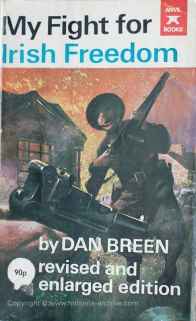

Robinson’s contention was that Breen had falsely made several claims about his role in the War of Independence through his 1924 memoir, My Fight for Irish Freedom. It was a case he would make repeatedly, in his Statement and in the numerous letters he wrote to various newspapers or individuals and later collected in the appendix of his Statement.

Robinson’s contention was that Breen had falsely made several claims about his role in the War of Independence through his 1924 memoir, My Fight for Irish Freedom. It was a case he would make repeatedly, in his Statement and in the numerous letters he wrote to various newspapers or individuals and later collected in the appendix of his Statement.

Not all the letters were written by himself, for he had adopted an ally in his war of words: his sister-in-law, Kathleen Kincaid. While too young to contribute anything herself during the War of Independence, Kincaid was steeped in the struggle by virtue of her family home of 71 Heytesbury Street, Dublin. This had been used as a safe-house and meeting-place for those on the run, including many famous names such as Ernie O’Malley, Seán McBride and Liam Lynch, among others, and she claimed to have “met or saw and heard nearly everyone of the real fighting men” through this.[3]

Kincaid wore her address as a medal of honour; when the luckless editor of the Sunday Press refused to print an earlier letter on the grounds of excessive length, Kincaid began her response by unsheathing the sharp edge of her research skills:

Dear Mr Feehan,

As you see, I have learned your name. I have also learned you are a South Tipperary man from Clonmel.

(The Dear Mr Feehan having omitted his name and address in his preceding rejection of her earlier letter, to no avail)

…and then by challenging him on his suspicious absence from the 71 Heytesbury Street Hall-of-Fame:

I met many men and some women from Clonmel in the old days of “71”; but I never heard of you. You must have been as young as myself – too young to do anything…What do you say?[4]

Feehan very sensibly did not venture an answer to that one.

Given her zeal for her brother-in-law’s cause, the historian Joe Ambrose decided that “Robinson clearly looked over Mrs Kincaid’s shoulder as she wrote” as if she was merely a convenient pen for Robinson.[5] But when comparing her letters with his, their writing styles were very different: his with a tendency towards long-windedness and waffling around the issue, while she wasted little time in getting to the point and going for the jugular. Whatever else one may think of the woman and her letters, she was a believer.

Making Claims

While not included in every letter of theirs, Robinson’s and Kincaid’s main points of contention were that Breen had been:

- Never elected Brigade O/C and had never obtained rank above that of Quartermaster.

- Not present in the attacks on the RIC barracks at Drangan or Hollyford, or indeed in charge of any fight.

- Wounded ‘only’ two times – once below the collar-bone, and the other through the calf – and not twenty-two times as claimed.[6]

The first two points will be addressed further in the article. The third one is hard to prove either way without access to Breen’s medical history, but as two bullet-wounds are still two more than what most people have had in their lives, it was perhaps unduly petty on Robinson’s part to make an issue out of it.

Nonetheless, it was an attack point Robinson pressed upon in a private letter to a friend. Writing in 1952, Robinson tarred Breen with the worst brush that a Fianna Fáil member and former Anti-Treatyite could tar another with: association with the ‘Staters’:

The Staters gave Dan Breen a house and a farm, gave him 200% of disability pension (he had only two bullet wounds in the whole of his I.R.A career in Ireland – wounds that healed up immediately and, why did these same Staters, when they got back to power as a coalition, in the first 24 hours, almost, of their existence rush through a bill through the Dáil granting him (not by name!) £3,000 for Doctors’ bills “contracted in the U.S.A.”[7]

The coalition mentioned had been the Inter-Party Government of John A. Costello. Twenty-eight years after the end of the Civil War and the opposition party was still ‘the Staters’. For Robinson, as with others, the past war had never really ended.

Robinson’s picking at this scab was perhaps aggravated by his own wrangles with medical pensions. In 1940, he applied for expenses for the damaging effects on his health caused by the irregular meals, damp conditions and the like from being on the run during his IRA days. This claim lingered in bureaucratic limbo until 1943, when a medical examination was arranged for Robinson in order to assess the validity of his claim. Robinson did not attend the appointment and when contacted further by the Army Pensions Board, dropped his claim altogether.[8]

Et Tu, Tipperary?

Breen’s enablers in what Robinson dubbed with entertaining bombast ‘the Great Tipperary Hoax’ were none the less than the people of Tipperary. Or so Robinson claimed in an unusual theory as to why his side of the story was not common knowledge already.

A native of Belfast, Robinson believed that the Tipperary people preferred to embrace one of their own, the Tipperary native Breen, as the hero in the War of Independence in their county. “Truth in a noose when it comes to trying to get any Tipperary man to expose the ‘Great Tipperary Hoax,” Robinson was supposed to have muttered to Kincaid upon hearing of how another of her letters had been rejected.[9]

Plaintively, Robinson professed to hold out hope that someday there would appear “some generous-minded Tipperary man to undo at least some of the ungenerous treatment I have received.”[10] As of yet, no such generous-minded native of Tipperary has emerged.

Who’s in Charge?

Robinson had been O/C of the Third Tipperary Brigade when it was formed in October 1918, with Seán Treacy as Vice Commandant, and Breen as Quartermaster. But Robinson was to frequently complain that Breen had falsely passed himself off as the O/C in Robinson’s place. The famous wanted poster of Breen, identifying him as the one who “calls himself Commandant of the Third Tipperary Brigade” was a particular source of frustration for Robinson, especially as it continued to be reprinted in books afterwards.[11]

As Robinson’s claim to fame was in large part his command of one of the most renowned fighting units in the War of Independence, it is understandable that such a hierarchical intrusion would infuriate him.

Breen did say in his memoir that he had been O/C but before Robinson, in the spring of 1918, prior to the official forming of the Brigade.[12] The wanted poster was printed after this time, when Breen was wanted for murder, so it can be explained by the authorities’ information being out of date.

Robinson insisted that Breen had never had a position higher than that of Quartermaster. But a contemporary, Patrick O’Dwyer, remembered Breen as the O/C around the time of October 1918, suggesting that Breen had held the post up to Robinson’s election.[13] Robinson was either wrong or refused to consider any Brigade position before that of October 1918 as legitimate.

The Man Not Present?

Perhaps the most serious claim of Robinson’s is that Breen lied in his memoir about being present at the assaults by the Third Tipperary Brigade on the Hollyford and Drangan Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Barracks, the former on the May 1920 and the latter on June 1920.

A possible tie-breaker here is Ernie O’Malley, who helped lead the attacks on Hollyford and Drangan Barracks with Robinson. O’Malley wrote accounts of his own, first as in his War of Independence memoir, On Another Man’s Wound, published in 1936, and later a series of articles in the mid-1950s that were published under Raids and Rallies.[14]

In O’Malley’s accounts of the Hollyford-Drangan attacks, Breen does not appear in either, though he does in the assault on the Rearcross barracks, which Robinson did not deny. Had he been present at either Hollyford or Drangan, it would have been strange for Breen to have not made a mention of it, given how well know Breen would have been to O’Malley’s readers. Thus we may tentatively conclude that Breen did lie about having been present at the Hollyford-Drangan attacks, and that Robinson was entirely correct in this.

Father Colmcille

The letters collected in the Statement’s appendix pertain to a number of subjects from this period. Of those letters centring the ‘Danbreenofile’ distortion view of history – as Robinson, with his flair for phrase-making, put it – four were written by Robinson.[15] One was to the Irish Press, and had been refused publication. The other three were part of the same convoluted mission and require an explanation onto themselves.

While a casual reader browsing through the appendix may think at first that these three letters were unrelated except in subject material, they were written together in response to a planned book about the Third Tipperary Brigade by a Father An tAthair Colmcille. Samples of the text had been published in the Irish Press, and Robinson had had the chance to read a typescript of the book, given to him by Seán Fitzpatrick, his former Brigade adjutant, who had been asked to check it for inaccuracies by Father Colmcille. Robinson had his own opinion on its accuracy: “On the whole I prefer Buck Rodgers.”[16]

Robinson could have written to Colmcille directly but, for reasons known only to himself, did not. Perhaps he found the prospect too distasteful. Instead of this obvious route, Robinson instead had all three letters mailed together to Abbot Benignus Hickey of Mellifont Abbey in Co. Louth.

The first letter was addressed to Abbot Hickey, asking him to pass on the second letter to Seán Fitzpatrick, then a resident of the Abbey, it would seem. It was an impressively long letter, and Fitzpatrick was treated to no less than two postscripts. The third letter was ostensibly addressed to W. F. O’Connell, secretary of the Soloheadbeg Memorial, with the intent of turning down a recent invitation but which was, at Robinson’s request to Hickey, to be passed on to Colmcille who was either another resident of the Abbey or in contact with its abbot.

As told to Abbot Hickey, the two letters to Fitzpatrick and O’Connell were intended to address the points in Colmcille’s upcoming publication. A good Catholic, Robinson made sure to stress that his rebuttals were intended for “Father Colmcille, the Tiperaryman-Historian – not the priest, God bless him,” and ending the letter to Hickey with a request that the Abbot pray for him.[17]

‘A Locker-Room of Deadly Shots’

That Colmcille was being singled out as an historian and not for anything else about him must have been scant comfort when reading remarks like: “I cannot make up my mind whether Father C. is simple (the virtue); or is a simpleton (within strict limits,” or threats of “a locker-room of deadly shots that I will discharge at his book.”[18] One can only speculate as to whether such remarks were intended to browbeat Colmcille into submission or if Robinson could not resist the chance to vent.

This triple-pack of letters prompted a mollifying response from Colmcille, who wrote with the wariness of a man moving slowly around a strange dog. Colmcille began by stressing that the typescript Robinson had read via Fitzpatrick had been a rough draft and not intended in any way to be publishable, a fact that Fitzpatrick was amiss for not making clear to Robinson. One could assume that this would be the last time Colmcille would ask Fitzpatrick for any editing favours.

The second defence was to deny any contact with Breen as a source, and minimise his use of Breen’s book for his own beyond a few quotes. Colmcille ended his letter with an invitation to forward his typescript to Robinson for any amendments he would want to make. If Robinson sent a reply, he did not include it in his BMH Statement, so we do not know what he made of Colmcille’s olive branch.

Motives?

Three other letters in the appendix were written by Kincaid to the Irish/Sunday Press, all refused publication. The reason given by the above Mr Feehan for refusing one of her letters was “pressures of space” and indeed the letter in question was a fairly long one, as were the letters in general.[19]

As all these letters to newspapers were rejected, it begs the question as to why either Robinson or Kincaid did not simply write shorter letters if they were so keen for Robinson’s version of events to be heard. It could be that the letters were never intended to be published. After all, that would have brought the ill feeling to public light, which would have been awkward given how the two men were both members of the same party in Fianna Fáil – Breen as a TD, Robinson as a trusted bureaucrat. Instead, it could be that Robinson passively-aggressively sabotaged his own efforts by intentionally making the letters too long for any editor to realistically consider printing them.

As for why write them at all, Joe Ambrose has suggested that even with the letters rejected, “the whole of Dublin would hear about their contents”, in a sort of guerrilla war by rumour. However, there is no indication that knowledge of the letters’ contents went beyond the offices of the Irish Press, let alone that that was Robinson’s intention.[20]

Equally questionable is Ambrose’s suggestion as to why Robinson added these letters to the appendix of his BMH Statement: “The result was a time bomb from another era, recently exploded, that was designed to wipe out Breen’s reputation and the credibility of his book.”[21]

Equally questionable is Ambrose’s suggestion as to why Robinson added these letters to the appendix of his BMH Statement: “The result was a time bomb from another era, recently exploded, that was designed to wipe out Breen’s reputation and the credibility of his book.”[21]

As Robinson never hinted at any plan as long-term as that, or any plan at all, it is impossible to say for sure. An argument against this is how the BMH Statements were only to be made available upon the death of their last contributor, Robinson included, which was not to be until 2003, forty-two years after Robinson’s death in 1961.

A plan of vengeance whose culmination the perpetrator could not be around to enjoy could hardly be a satisfying one. But for a man with a lot to say, Robinson could be stubbornly opaque as to what he hoped to achieve. All a historian can do is shrug and apply a question-mark over his motives.

Books Make the Man

On a similar note, it is a mystery as to why Robinson, if he was so aggrieved at Breen’s use of memoir-writing to inflate his role, did not respond in kind and write his own? Robinson adopted a puzzled, almost irritated reaction to that sort of question:

Quite a large number of people have been asking me from time to time, mostly importunately, during the last thirty odd years to write my memoirs. Why, I don’t know.[22]

He mentioned in a letter his “manuscript notes for, perhaps, a book – certainly a statement,” indicating that he was at least entertaining the idea of a memoir.[23] The way the Statement was divided into chapters, with a prologue, separate chapters, and an appendix, further suggests that it was intended to be the makings of a publishable book.

Robinson had previously contributed an earlier Statement, in 1948, this one limited to specific themes in his revolutionary career:

- His family, early years and Volunteer activities in Glasgow up to 1916.

- A list of names of those in the ‘Kimmage Garrison’ of the Easter Rising.

- His role in the Rising as part of the ‘Kimmage Garrison’.

- A 1932 Evening Telegraph article on the Lord French Ambush, written by the then-Senator Robinson.[24]

This one was composed in 1948, nine years before Robinson wrote his main one in 1957. It is the shorter of the two, at 26 pages including newspaper clippings, while the material in the 1957 one totals 142.

Through the difference in the two Statements, one can see the writer’s progression from the short pieces in the first to a more complete narrative and arguments that make up the second. Also notable is how Breen is barely mentioned in the first, in contrast to the spleen displayed against him in the second. Presumably Robinson lacked the self-assurance to do his cause justice initially.

By the time he composed his second Statement, he had grown in confidence as a writer and in the certainty of himself as a wronged man. Robinson seemed to be building himself up to write something greater, perhaps a magnum opus of his life’s work and vindication?

But, ultimately, Robinson went no further. He never provided a book nor an answer as to why other than indifference on his own part, when of course Robinson was anything but indifferent. He clearly had the ability, time and passion to write a memoir of his own, and there was certainly a demand for stories from the War of Independence which Breen, O’Malley and others were happy to supply, but for whatever reason Robinson never followed suit.

Conclusion

The BMH Statement of Séumas Robinson is one of the most colourful to have emerged from the vaults of the Bureau of Military History. The reader is struck by the vitriol displayed by Robinson towards his colleague, Dan Breen, an indignation that formed around a number of claims Breen had made through his memoir: Breen had been Brigade O/C, he had been present at the assaults on a couple of RIC barracks, and he had exaggerated the extent of his injuries. Breen was enabled in his deception, or so Robinson believed, by the people of Tipperary who preferred to celebrate one of their own at the expense of the Belfast-born Robinson.

And so Robinson embarked on an underground literary career, assisted by his sister-in-law, in writing letters of complaint about Breen’s deceptions to an assortment of newspaper editors, historians and abbots. Why he did not pursue the same aims through more productive methods such as shorter letters or publishing his own memoirs is a mystery, as are his motives in general for his extensive, but ultimately futile, letter-writing campaign.

Originally posted on The Irish Story (08/12/2014)

See also:

Never Lukewarm: Séumas Robinson’s War of Independence

Demagogue: Séumas Robinson and the Lead-up to the Civil War, 1922

References

[1] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 3

[2] Ibid, p. 5

[3] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 95

[4] Ibid, p. 100

[5] Ambrose, Joe. Dan Breen and the IRA (Douglas Village, Cork: Mercier Press, 2006), p. 178

[6] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), pp. 87-88

[7] Ibid, pp. 121-122

[8] Robinson, Séumas, Military Service Pensions Acts 1949 (Accessed 29/11/2014)

[9] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 100

[10] Ibid, p. 119

[11] Ibid, pp. 86, 125, 128-129

[12] Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), p. 19

[13] O’Dwyer, Patrick H. (BMH / WS 1432), p. 6

[14] Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom, pp. 107-110 (Hollyford), pp. 112-118 (Drangan)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound, pp. 189-195 (Hollyford), pp.200-203 (Drangan)

O’Malley, Ernie. Raids and Rallies (Cork: Mercier Press, 2011), pp. 21-41 (Hollyford), pp. 42-60 (Drangan)

[15] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 118. In case one wonders what the ‘usual concomitant’ of this is, it is ‘S.R.-opobia’.

[16] Ibid, p. 127

[17] Ibid, p. 117

[18] Ibid, p. 118, 119

[19] Ibid, p. 99

[20] Ambrose, p. 178

[21] Ibid

[22] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 3

[23] Ibid, p. 101

[24] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 156)

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History / Witness Statements

O’Dwyer, Patrick H., WS 1432

Robinson, Séumas, WS 156

Robinson, Séumas, WS 1721

Books

Ambrose, Joe. Dan Breen and the IRA (Douglas Village, Cork: Mercier Press, 2006)

Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

O’Malley, Ernie. Raids and Rallies (Cork: Mercier Press, 2011)

Military Service Pensions Acts 1949

Robinson, Séumas (Accessed 29/11/2014)