Attack on the Hibernian

The 24th January 1922 was a quiet Tuesday for the town of Mullingar, Co. Westmeath, what with it being a half-holiday and almost all business closed for the day. An exception was the Hibernian Bank and even that was nearing its closing time of 3 pm when three armed men entered.

With one of the new arrivals standing by the doorway with his revolver and the second holding the staff at gunpoint, the third entered the manager’s office where an accountant had been talking with a customer. After cutting the telephone connection, the third intruder demanded the keys to the strong-room, only to be told by the accountant that the keys were with the manager who was away.

Frustrated, the raider left the office and proceeded to the teller’s box which he quickly cleared of its contents. Having seized the most they could get, the robbers left the bank and drove out of Mullingar with their ill-gotten gains.

Despite the severed telephone connection, the bank staff were able to quickly call for assistance. Lorries with members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) inside drove down Mullingar at top speed in pursuit. For many onlookers, this was the first indication that something amiss had occurred. Both the RIC and the Irish Republican (IR) police, enemies united in common purpose, were soon scouring the outlying roads for any trace of the fugitives.

It had been, reported the Westmeath Guardian newspaper, a misdeed of a “particularly cool and daring nature.”[1]

Dublin

The Mullingar raid had not been an isolated event. A second Hibernian Bank branch was hit on the same day, this time the one in Dublin, Thomas Street. Unlike that in Mullingar, this heist was no hurried affair. A single man entered the bank, arousing no suspicion from staff who assumed he was another customer.

After waiting for an opportune moment, the scout gave a signal for a group of nine or ten men to swiftly enter the building in single file. “Hands up,” called the first man as he and his colleagues pulled out revolvers and herded the staff and customers into the manager’s room. The two tellers were then brought out and ordered to give up the keys to the cash drawers. A robber went so far as to put his gun to the face of one of the tellers and threaten to shoot if he did not do as he was told.

After the bank premises were thoroughly searched, the raiders made their getaway, also by motorcar, with as much money as they could lay their hands on. It was not the first heist that had occurred in Dublin since the Truce of the year before, but it had been one of the biggest.

Delvin

The next day, Co. Westmeath, again saw another bank raid, this time against the Ulster Bank in Delvin. This one was slightly more complicated than the other two from the day before. The robbers entered the bank at 2 am and abducted the manager who was presumably working late.

The kidnappers drove their captive some five miles away to the residence of the bank cashier. After he had been threatened into handing over his keys to the safe, the robbers drove back to Delvin, re-entered the bank and helped themselves to the contents of the safe.

The only trace found of the three robberies was the motorcar used in the Mullingar one. It had been abandoned in a laneway about six miles from Dundalk, having been stolen from its owner in Lisburn. The near simultaneousness of the heists and the distance travelled by at least some of their perpetrators indicated that they had been more than local affairs.[2]

Law and Order

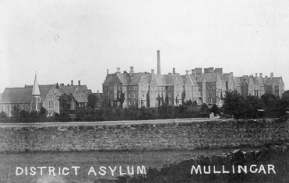

Exacerbating the situation was the near absence of policing. This was not necessarily due to the lack of policemen. In February, Mullingar found itself playing host to around 600 members of the RIC from various counties in the soon-to-be Free State, who arrived to take up residence in the town’s military barracks.

Exacerbating the situation was the near absence of policing. This was not necessarily due to the lack of policemen. In February, Mullingar found itself playing host to around 600 members of the RIC from various counties in the soon-to-be Free State, who arrived to take up residence in the town’s military barracks.

They were not there to help, however, but to await disbandment as per terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The local publicans, it was noted wryly, were not doing at all badly by the new arrivals, but that would do nothing to deter the rising rate of crime.

Mullingar, in the opinion of the Westmeath Guardian in February, was one of the most backward towns in Ireland regarding law enforcement. The newspaper was sure that the IR Police, formed from the local Irish Republican Army (IRA), were doing their best but they alone could not solve the matter. Mullingar had no excuse; after all, smaller towns than it were organising their lawmen into patrols and placing guards by banks. That Mullingar was not following suit left it a wide open target.[3]

A crime surge at the start of April showed how little had been done. On a single day, two motorcars were stolen in Mullingar, one at gunpoint, with another two unsuccessful attempts. Vehicles were not the only prized acquisitions. A lorry leaving Mullingar with demobilised RIC men was held up and the firearms and ammunition seized.

“The incident,” according to the Westmeath Guardian, “created much excitement in the vicinity at the time.” [4]

As well it might. These crimes were symptomatic, not just of the disintegration of law and order but of the growing tensions between the two factions split over the signing of the Treaty, for the robberies were not simply the works of a lawless element. There were those who believed they would have use of such firearms before the question was resolved.

‘The Interests of the Nation’

Speaking in Mullingar Cathedral at the first Mass of 1922, the Most Reverend Dr Laurence Gaughran, Lord Bishop of Meath, asked his congregation to pray for the ratification of the recently signed Treaty. In this, the Bishop could claim to be reflecting the views of many in the area.

The day after the sermon, the fifteen members of the Westmeath County Council met to deliberate on the matter. After half an hour, a resolution in favour of the Treaty was drawn up for discussion. Their elected representatives were urged to support the ratification when the time came in the Dáil; at this point, a slight edge entered the tone of the text:

In passing the resolution, which, we believe, expresses the desire of the vast majority of the people of Westmeath, with whom we are, perhaps, in more intimate touch than the Dail representatives of the country, we have at heart only the interests of the nation. [5]

It is unsurprising that the Council would feel estranged from, and suspicious of, their representatives. After all, two of the four TDs for Longford-Westmeath had been largely absent during the past few years, with Laurence Ginnell abroad in the United States and South America, and Seán Mac Eoin busying himself with the guerrilla war in Co. Longford before his imprisonment.

As it turned out, the anti-Treaty Ginnell was absent for the Treaty vote and with the other three – Mac Eoin, Lorcan Robbins and Joseph McGuinness – voting for the Treaty, the Council need not have worried.

Chaos or Creation

The Council resolution had been proposed by Seán O’Hurley, the one-time O/C of the Athlone IRA Brigade who had stepped down to focus on the political aspect of the burgeoning Republican movement. Described by a contemporary as a “terrific worker” with “great skill and energy”, O’Hurley wore his heart on his sleeve where the Treaty was concerned. It would, he said, provide Ireland with the power to reach a full and independent Republic. To reject the Treaty would lead to chaos, while to accept it meant creation.[6]

A few of his colleagues were less enthusiastic. While saying he was in favour of the resolution, H.R. O’Brien objected to how the press was trying to stampede the people into acceptance as he saw it. A second man, M. O’Reilly, proposed an amendment, seconded by another, Gavin, reaffirming allegiance to the Dáil Éireann but otherwise take no further action. When this amendment was ruled out, O’Reilly, Gavin and a third councilman left the room.

The rest of the Council had no such reticence. J. Lyons said that he had been instructed by the workers of Moate to vote for the resolution of ratification; while it is impossible to verify this claim, it does indicate – if true – that the favouritism towards the Treaty was more than a top-down decision on the part of the Council. With obvious enthusiasm, P.J. Weymes told of how every other council in Ireland had declared in favour, while P. Brett chimed in with how international recognition would secure absolute independence for Ireland.

And it was with these sentiments that the resolution for the ratification of the Treaty was passed. It had not been an uncontentious decision but considering the abuse Westmeath had endured in the past year, perhaps there was no other way it could have gone.[7]

The War in Westmeath

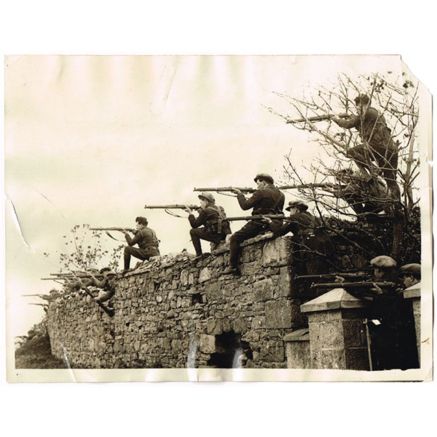

For two and a half years, from January 1919 to the Truce of July 1921, Ireland had suffered war and occupation. Soldiers had patrolled in armoured cars while guerrillas hid behind hedgerows or around street corners. Bodies had been found bullet-ridden, killed for one reason or another.

At the start of January 1921, James Blagriffe, a labourer and ex-serviceman in the British Army, was abducted near Athlone. His corpse was found in a kneeling position with the hands clasped and a placard around the neck with the word ‘Spy’. The surrounding ground had been ploughed up by bullets, suggesting a hurried and haphazard execution.

Statements in the Bureau of Military History would confirm that Blagriffe had been murdered by the IRA, although the label of spy was a misnomer – he had been planning to join the RIC which, with his local knowledge, would have made him too big of a liability.[8]

In the same week, armed men in civilian clothes entered the Coosan district, also near Athlone, and unsuccessfully tried to burn down a house after forcing out the occupants. Another home was threatened if the owner did not reveal the whereabouts of his sons, although the assailants later withdrew empty-handed. The identity of the would-be arsonists is unknown, though it seems likely that they were British soldiers or Crown policemen in mufti, seeking reprisals and IRA men on the run.

In the same week, armed men in civilian clothes entered the Coosan district, also near Athlone, and unsuccessfully tried to burn down a house after forcing out the occupants. Another home was threatened if the owner did not reveal the whereabouts of his sons, although the assailants later withdrew empty-handed. The identity of the would-be arsonists is unknown, though it seems likely that they were British soldiers or Crown policemen in mufti, seeking reprisals and IRA men on the run.

Public administration suffered, with the results all too evident. The streets of Mullingar accumulated a layer of filth, mud and manure, particularly in Dominick Street after the cattle-markets held there due to the lack of maintenance. Public lighting dimmed, the ignited gas in the lamps being of such poor quality that it was barely worth venturing out at night.[9]

‘This New Phase in the Irish Situation’

But running parallel to the battles, barbarity and squalor, there had been occasions for good cheer and festivity. Men from the East Yorkshire detachment were on their way from Carrick-on-Shannon to their headquarters in Mullingar when they came across a torchlight procession for the New Year celebrations of 1921.

Soldiers and civilians joined hands and danced to the music of the accompanying band while hearty cheers and good wishes were exchanged. The Suffolk Regiment who arrived to replace the Yorkshiremen “looked on in astonishment from their barracks in the courthouse, and seemed unable to understand this new phase in the Irish situation.”[10]

The situation entered a new stage upon the Truce in July of the same year. So great was the relief that the fighting had ended, at least for a while, that civilians and members of the Crown forces participated together in an impromptu swimming contest in the Shannon on the 12th, only a day after the Truce had come into effect. Crowds of both sexes danced and sang before a huge bonfire, and a procession marched through Athlone to the tune of Irish songs.

Even those who had been shooting at each other days before were caught up in the euphoria. A squad of soldiers in a lorry chanced upon a group of Volunteers from the IRA. As soon as they saw the lorry, the Volunteers stood to attention and saluted their adversaries who returned the gesture. Soon both parties were waving handkerchiefs at the other as they passed on by.[11]

Departures

Equally affable was the gradual withdrawal of the British garrisons. The last of the feared Black-and-Tans stationed in Mullingar had left by the end of January-February 1922, leaving the regular soldiers and policemen to say their farewells to the local people they had been stationed with.

On the 3rd February, a concert was held in the Mullingar Military Barracks as a tribute to the departing Royal Sussex Regiment. In honour of the event, several pieces of verse by a budding wordsmith were published in the Westmeath Guardian:

They’d a concert for soldiers at the Barracks Tuesday night,

And sure as I’m a living soul, it was a lovely sight.

There were ladies, there were gentry, there were even RIC,

There were officers and soldiers and children on the knee.

The concert room was smallish, t’wasn’t gaudy, but ‘twas neat,

And the music that they gave us there you wouldn’t quickly beat,

For I’ve been with the Army to stations near and far,

But I’ve never had such fun before as I’ve had at Mullingar.[12]

One could debate the quality of the poetry but it captures the general ambience well enough.

As if not to be outdone, a ceilidh was organised in the Mullingar County Hall for those who had been imprisoned during the past troubles. Four hundred people were estimated to have attended, making it one of the most successful events of such a kind ever held in the town.[13]

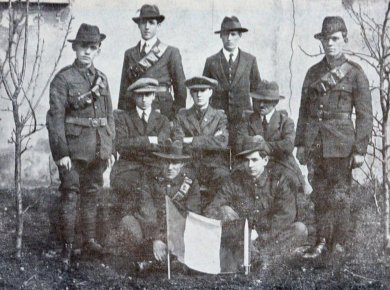

The Handing of the Barracks

The goodwill continued with the handover of the various police and army barracks to the new military authorities. The one in Mullingar was occupied on the 13th February by the IRA under the command of James Maguire, the O/C of the Mullingar Brigade since mid-1920. The move was purely formal as the IRA was due to move out to make room for the RIC members from around the midlands who were awaiting disbandment. The officer in charge of the old police force until then, District Inspector Harrington, called on the editors of the local newspapers to assure their readers that the reoccupation was to be temporary and for there to be no misunderstandings.[14]

Otherwise, the handovers continued. Castlepollard Barracks was surrendered to a company of forty Volunteers, again led by Maguire. The O/C must have wondered at the turn of fortune, for he had led a brief and unsuccessful assault on the same barracks a few hours before the Truce was due to take effect the previous year. Now, a tricolour was hoisted from the chimney of the building to the rousing cheer of the assembled crowd.[15]

Maguire and the other Volunteers were not the only ones taking advantage of opportunities. HUGE PURCHASE OF MILITARY STORES AT BARGAIN PRICES, so read the advertisement in the papers for Nooney & Son, Mullingar. Among the goods the store had recently purchased were barbed wire, fencing stakes and barrack room tables.

Decommissioning

For all the good fortune, danger still lurked. A small boy picked up a detonator from the deserted Castlepollard Barracks and brought it home to his mother. The woman was unwisely inspecting the strange object when it exploded, stripping the flesh off a finger and thumb and part of her palm.[16]

It was to prevent further accidents that the Volunteers destroyed the military munitions left behind in the Mullingar Military Barracks. A lake on a nearby estate was selected for this purpose, and large amounts of bullets and bombs were taken there by lorry and dumped in.

On the 29th March, more equipment in the form of Vesey rockets, gun cotton, bombs and the like were thrown into a trench dug in the yard of Mullingar Barracks and set ablaze. Unfortunately, the handlers had not taken into account the effect of fire on explosives and no one had warned the townspeople who were surprised and terrified by the sudden explosions that shook their houses and lit the evening sky.[17]

While the stray armaments had at least been put beyond use, the hope that the future would be a peaceful one would be revealed as being overly optimistic.

Build Up

The latter half of April 1922 saw Mullingar become a divided town as more soldiers from both factions on the Treaty divide were brought in by lorry on a daily basis. The Free State soldiers were in possession of the Military Barracks and the Post Office, with their Republican counterparts quartered in the County Buildings, New Technical School and the Police Barracks. Mullingar increasingly resembled an armed camp.

Local traders felt the pressure keenly as their goods, particularly food, cooking utensils and clothing, were commandeered. The anti-Treaty IRA appeared to have been the worse, with reports of them venturing out of town to steal livestock. They did not have things entirely their way. On the 25th April, two of them were arrested by Free Staters on the corner of Earl Street while a crowd of spectators looked on. The prisoners did not go quietly, managing to let off a couple of shots before they were subdued.

If the Free Staters had been attempting to restore some semblance of order, then it was a case of too little, too late. On the same day, half a dozen post offices in villages near Mullingar, such as Moyvore, Tang and others, were robbed of their money. The multiple raids coincided with the seizing of six Free Staters who were careless enough to be caught unarmed while in a barber’s shop.

Bloodshed

The inhabitants of Mullingar were roughly awakened on the Thursday morning of the 27th April, a little before 6 am, by the sounds of machine guns and rifle-fire. An alteration of some kind broke out which escalated into shots being fired. Alerted by the commotion, reinforcements from both sides rushed to the scene, prompting another shootout, this time with the addition of a machine-gun brought along by the Free Staters. The skirmish continued for half an hour before a priest, the Rev. J. Kelly, braved the scene and succeeded in appealing to the combatants to withdraw.

Two men on either side had been killed in the exchange. Pools of blood were left in Dominick Street, Mary Street and Bishop’s Gate Street, but it was the first that had borne the brunt of the battle. Bullet holes scarred the walls and the windows of several houses had been broken.

Several shops in town only opened around midday when peace had been thoroughly restored, the warring sides having returned to their own quarters. Desultory shots were heard in Earl Street and Blackhall Street but with no further causalities reported.

Not taking any chances, Free State troops threw up a barricade of iron gates, water barrels and carts across Patrick Street, blocking all traffic through there for a considerable amount of time. Shoppers in Mullingar also erred on the side of caution, with the cattle-fair cancelled for the day and the remaining markets only sparsely attended.

Mullingar Police Barracks

Despite the lack of a clear winner from the fighting, the Anti-Treatyites were sufficiently unnerved to abandon their bases in the Police Barracks, Courthouse, County Hall and Technical School, taking their food and bedding with them in the night.[18]

One of those buildings, however, did not survive the following week. At around 8:30 pm on the 3rd May, a large explosion tore through the Police Barracks, followed by black, heavy smoke emerging from the windows and roof. A portion of the wall had been blown out and the resulting fire threatened to spread to the rest of the street.

The burning barracks presented a fearsome sight, described by the Westmeath Guardian as towering “high above the town, and the streets all round were illuminated by the flames leaping from the roof, windows and doorways of the barracks.”

The fire brigade sprang into action and, assisted by Free State troops and the staff of the nearby Post Office, they were able to use their hoses in containing and then extinguishing the inferno. The barracks, described as “one of the largest and most modern of its kind in the provinces,” was left a gutted shell that continued to smoulder for days after.[19]

The Westmeath Guardian gave no indication as to the culprits. Years later, however, the veteran Republican Con Casey related to historian Uinseann MacEoin how it had been him and another man who had set the explosives in the barracks. Had the Anti-Treatyites stood their ground in Mullingar instead of withdrawing, Casey mused, the Civil War might have begun earlier there instead of at the Four Courts.[20]

“Let him have it”

Subsequent inquiries attempted to flesh out the events of the battle, during which it emerged there had been two separate flashpoints that day. At the hearing into the death of the Free State soldier held a day afterwards, his commanding officer, Captain Conlon, told of how he had dispatched some of his company under Captain Casey to the Police Barracks that morning, their aim to secure the release of their six colleagues kidnapped in a barber’s shop two days before.

Casey confirmed this, and continued the account. As he approached the enemy-held barracks with his men at his back, he saw the heads of those inside through the windows and heard a voice call out: “Let him have it.”

“It is alright, don’t fire,” Casey had replied to no avail.

The men in the barracks opened fire, accompanied by some others who were behind a lorry parked nearby. The Free Staters hurriedly retreated, at which point Casey met with Patrick Columb, the company adjutant.

“I am wounded, but it doesn’t matter, we will fight it out,” Columb had bravely said, according to Casey’s recollections.

Columb was found later in a house in Mary Street and in considerable pain from a gunshot wound. He was taken to the Mullingar Barracks where he died. The fatal bullet was found in the back of Columb’s shoulder, having passed through the covering of the left chest to emerge on the right side, close to the spinal column.

The inspecting medic concluded that the shot had been made at close range judging from the slight scorching on the skin. Although the perforated lung would alone have been grievous, the official cause of death was ruled to have been internal bleeding.

Casey emphasised how there had been no shooting until the Anti-Treatyites started it. The jury returned with a verdict of wilful murder in the case of Columb by person or persons unknown. As that had been the verdict asked for by the solicitor for the military authorities, the Free State Army could be reasonably satisfied with it.[21]

Joseph Leavy

The inquiry into the other fatality – that of Joseph Leavy on the anti-Treaty side – did not go as smoothly, at least not at first, being adjoined for a month due to the jury not being convinced there was enough evidence to show how the deceased had received his wounds. The hearing reconvened on the 16th May, this time featuring testimony from Anti-Treatyites who had been taken prisoner during the battle.

Walter Walsh told of how, on the morning of the 27th April, he and some other men, including the late Leavy, had been delivering bedding to their comrades in the Police Barracks. Having finished, the men were being driven back in a lorry and were at the head of Mary Street when they were halted by Free State soldiers and told to put up their hands, which they did. Then they were ordered to put aside their arms and come out of the lorry.

After the passengers had done so, the driver had had second thoughts and put the lorry in reverse. The Free Staters responded by opening fire on the lorry, out of which the driver leapt and ran away. The remaining Anti-Treatyites were marched down Mary Street with their hands above their heads. When they had turned at the corner of Dominick Street, they were fired upon from the Post Office with rifles and a machine-gun.

The prisoners fled to shelter by the sides of the houses. Lying flat on the ground, Walsh saw Leavy fall and lie motionless. When the firing had ceased, the Anti-Treatyites were once again rounded up and taken to the front of the Post Office, where they were searched and then transferred to the military barracks.

Questions (and Answers?)

Several questions were asked from the jury:

Q: How many soldiers were guarding you?

Walsh: About a party of fifty men.

Q: Did the guards make any attempt to stop the firing?

Walsh: I did not hear any order to cease firing. We were all disarmed when we came into Dominick Street. There was no reason whatever for fire being opened.

To another question, Walsh replied: “I could not say if there was firing from the back.”

Another witness, Laurence Gibbon, was sworn in and corroborated what Walsh had said:

Q: There were no shots fired from behind?

Gibbon: Not as far as I could see. I could not see what stopped the firing. Free State troops ran for shelter as well.

Q: Did they prevent you taking shelter?

Gibbon: No. They did not tell us to take shelter.

One of the jurors was visibly disgusted: “They drove them into an ambush and then took shelter themselves.”

The third witness, James Nally, confirmed that there had been no firing when the prisoners entered Dominick Street and that, in his opinion, they had been fired upon.

Q: Was it deliberately or accidently you were fired upon?

Nally: I could not say, sir. The firing in Mary Street was not accidental. I cannot say was the guard under fire, but they were before us and behind us.

After ten minutes of deliberation, the jury returned with a damning verdict: Leavy had met his death from bullet wounds while a prisoner with hands up and unarmed. Unsatisfied with how things stood, the jury called for yet another inquiry to finally determine what had happened that day in Mullingar.[22]

Conclusion

A further hearing was thus set for the 19th May in Mullingar, to be attended by representatives from both the pro and anti-Treaty factions; however, the event fell through due to the absence of anyone from the former.[23]

The delayed inquest finally took place on the 1st June at University College, Dublin, this time attended by men from both sides. The hearing mostly reiterated what had been said at earlier ones. It was not even clear which of the two main incidents – the shooting outside the Police Barracks and Patrick Colum’s death or the capture of the Anti-Treatyites in the lorry and Joseph Leavy’s shooting – occurred first or to the extent that they were connected.[24]

While the exact chronology and causes must remain obscured by the fog of war, the basic facts were all too clear: the situation in Mullingar, with its armed bands and rampant lawlessness, had been bad before it worsened, and that of Ireland as a whole was unlikely to improve before it too intensified.

See also: Among the Philistines: Dissent and Reaction in the Mullingar IRA Brigade, 1921

See also: Kidnapped in Mullingar: An IRA Operation and its Aftermath, 1920

References

[1] Westmeath Guardian, 27/01/1922

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid, 24/02/1922

[4] Ibid, 07/04/1922

[5] Ibid, 06/01/1922

[6] O’Meara, Seumas (BHM / WS 1504), p. 16

[7] Westmeath Guardian, 06/01/1922

[8] Ibid, 07/01/1921 ; O’Meara, p. 51

[9] Westmeath Guardian, ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid, 15/07/1921

[12] Ibid, 03/02/1922

[13] Ibid, 10/02/1922

[14] Ibid, 17/02/1922

[15] Ibid, 24/02/1922 ; Maguire, James (BMH / WS 1439), p. 30

[16] WG, 24/02/1922

[17] Ibid, 31/03/1922

[18] Ibid, 28/04/1922

[19] Ibid, 05/05/1922

[20] MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), p. 375

[21] WG, 28/04/1922

[22] Ibid, 19/05/1922

[23] Ibid, 26/05/1922

[24] Ibid, 02/06/1922

Bibliography

Newspaper

Westmeath Guardian

Book

MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

Bureau of Military History / Witness Statements

Maguire, James, WS 1439

O’Meara, Seumas, WS 1504

On 4th November 1921, Michael Collins, as Director of Intelligence, wrote to the staff of the Mullingar IRA Brigade in Co. Westmeath. He had received a troubling letter about the arrests of two of its Volunteers: Patrick Dowling on 21st September, followed by Christopher Kelleghan on 22nd. Both had been singled out for subversive activities when they attempted to contact the GHQ of the IRA in Dublin.

On 4th November 1921, Michael Collins, as Director of Intelligence, wrote to the staff of the Mullingar IRA Brigade in Co. Westmeath. He had received a troubling letter about the arrests of two of its Volunteers: Patrick Dowling on 21st September, followed by Christopher Kelleghan on 22nd. Both had been singled out for subversive activities when they attempted to contact the GHQ of the IRA in Dublin.

By November, O’Sullivan had gathered enough preliminary evidence to proceed with an inquiry, to be held in Mullingar. The two co-defendants, for the inquiry was as much their trial, were present. O’Sullivan examined them and took their statements along with those from three of the others who had been dismissed from their Company.

By November, O’Sullivan had gathered enough preliminary evidence to proceed with an inquiry, to be held in Mullingar. The two co-defendants, for the inquiry was as much their trial, were present. O’Sullivan examined them and took their statements along with those from three of the others who had been dismissed from their Company.