Introduction

When Patrick Kane sat down to give his Statement to the Bureau of Military History (BMH) in 1957, he was a man who believed he had little to show for his efforts. He had served as an adjunct in the Carlow IRA Brigade during the War of Independence – no easy task considering the difficulties which faced the brigade and the setbacks that often frustrated the best of its efforts.

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, he chose the losing side and was imprisoned, a misfortune which he had previously been able to avoid. Upon his release in 1924, his employment status was to follow the ebb and flow of Irish party politics. Kane had to resort to working abroad until his return to Ireland, two years after the election of his former Civil War comrades in Fianna Fáil.

For the next twenty years, he was able to work in several Irish industries until he was forced to retire. That a Fine Gael-led government was then in power made it unlikely that he would receive much support besides an inadequate pension, and so Kane faced the fraught prospect of seeking work again at the age of sixty-two. “And so, another of my ideals and ambitions has one down in dust and ashes under my feet” was the bleak verdict on which he closed his Statement.[1]

Implied Reproach?

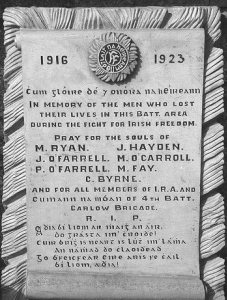

Anyone looking at the activities of the Carlow Brigade can be prone to a similarly gloomy mood. William Nolan, a rare historian to have approached the subject, admitted that: “Carlow does not have a very active fighting story. This may sometimes have been adverted to by way of implied reproach.” As a counterbalance, Nolan reminded his readers of the leading role Carlow had played in the 1798 Rebellion, as if to reassure them that red blood did indeed run through Carlow veins, after all.[2]

Kane did not bother comforting himself with historical allusions when he retrospectively assessed the difficulties the brigade had faced: the constant flux within the Brigade leadership, the lack of weapons and ammunition, and the unfavourable nature of the local situation towards guerrilla activities, such as the intrusive presence of the Curragh Camp.[3]

Yet the grass is always greener on the other side, in war as with other things, and the difficulties that plagued the Carlow Brigade were not so obvious to its enemy. British captain E. Gerrard was in Carlow at the time of the Truce (or ‘the Armistice’, as he called it, muddling up his wars) and was struck by the level of preparation deemed necessary by the British soldiers stationed there. Every field the soldiers occupied was made into an enclosure by trees they had cut down.

Gerrard could not help but wonder what the rest of the country would be like if such defences were needed for only twenty miles from the Curragh. To Kane, the Curragh was an insurmountable obstacle for the Carlow IRA. To Gerrard, that the IRA could operate at all near the Curragh was enough to make him doubt whether the guerrillas could be defeated.[4]

Organising the Brigade

The use of the name of the ‘Carlow Brigade’ is something of a misnomer. The perimeters that defined the scope of its activities covered considerable chunks out of Counties Kildare and Wicklow, as well as a corridor of land from Laois along the Carlow-Kildare border, meaning that three out of the six battalion areas were outside of Co Carlow.[5]

The battalions and companies were expected to be to a degree self-sufficient. They could not turn to their parent Brigade for resources for the simple reason that there was little to give. At the same time a certain amount of discipline through the battalions was the norm, with Volunteers expected to wait for orders before acting on an idea, even if it had originated from them.

This was generally adhered to, however frustrating: Nan Nolan, a Cumann na mBan captain, was working as a nanny in the house of a retired British army general when her brother in the Ballon company asked her to leave open a window on a prearranged date for him and his colleagues to steal the guns kept inside. By the time official permission for this home-invasion materialised, Nolan had left the job, depriving the company of its inside-woman.[6]

Such policy bred a cautious attitude within the Brigade, discouraging risk that could lead to disaster. That two of the more ambitious attempts – the creation of a flying column, and an ambush on a RIC patrol near Barrowhouse – would result in heavy losses for those involved would serve to justify this conservative approach.

Relations between officers with their colleagues in the Kildare and Wicklow Brigades were cordial – something that could not always be said for relations between different Brigades – and they occasional worked in unison together. An attack on Auxiliaries posted at Inistioge by a Kilkenny battalion was to be assisted by men from the Carlow 4th battalion, though the plan was cancelled just as the main force had assembled. More successfully, Liam Stack, the intelligence officer for the Carlow Brigade, was able to sit in on a Kilkenny IRA military court in relation to a local dispute.[8]

Maintaining Intelligence

Volunteers recognised early on the urgency of knowing before the enemy knew, the key method of achieving this being control of the mail. Through surreptitious supervision of the post offices and the occasional direct intervention on the flow of mail through the county, Volunteers were able to forewarn other ones of impending arrests, head off leakage from spies, and allow the brigade to keep riding with the enemy punches. Without its members’ skill at information warfare, it is unlikely that the Brigade could have survived long as a functioning military force.

Kane was assigned by his Brigade superiors the task of collecting what information he could. The proactive Kane had himself been elected to the National Executive of the Post Office Clerks’ Association. This gave him the scope to travel and make contacts with sympathetic workers in other post offices around the country, and by early 1920, Kane was part of a cell operating in Carlow post office with access to postal, telegraphic and telephonic communications.

Four of them remained active up to the Truce, though the cell was not impregnable. The point-man for passing information onto GHQ in Dublin, Pádraig Conkling, was forced on the run in later 1920 after being threatened with shooting by Black-and-Tans. Another member, Michael Carpenter, was imprisoned in 1921 for being in possession of illegal wire-tapping equipment. His arrest led to raids on the homes of other post office workers including Kane’s, who from then on was frequently held up in the street by suspicious Crown patrols.[9]

Despite these setbacks and the increasingly straitened circumstances, the intelligence work continued on, leading to many a timely tip-off. Sometime in 1921 – conflicting accounts place the date in either mid-April or a few days before the Truce in July – a British army regiment entered Ballon with the aim of arresting the Volunteers in the company there. The wanted men were forewarned in time to stay away from their homes until the regiment and the danger had passed.

However, the Brigade was unable to achieve complete dominance over the flow of information. As part of the same series of raids that had unsuccessfully tried Ballon, British soldiers were able to net several arrests in the area around Rathvilly, indicating that not only did the soldiers know who to look for, but that there had been a failure in the Brigade’s early warning system.[10]

The Burning of the Barracks

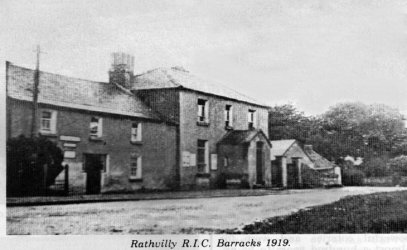

The Carlow Brigade had not attempted anything of note until its enemy unexpectedly gave it an opening. As part of a countrywide policy by Dublin Castle to consolidate its police force into fewer, less exposed strongholds, a number of RIC barracks in Carlow were closed in April 1920.

The abandoned buildings were razed by Volunteers when it became clear that their former garrisons would not be returning, giving the battalions their first taste of activity. That empty buildings make the easiest targets was an added bonus.

Even so, the campaign of destruction was not without incident: Richard Barry was badly burnt while helping to burn down Ballon Barracks. Craiguecullen Barracks was adorned by what Patrick Kane described as a “beautiful crest in cut-stone” which became a target for some Volunteers “with more enthusiasm than sense” who triumphantly hacked away at it.

A witness passed on their names in a letter to the police, though Kane, in his capacity at the post-office, was able to intercept the letter an hour later, after which the would-be informant was given twenty-four hours to leave the area. Kane described the culprit as a ‘loyalist’ though they may simply have been attempting to be civic-minded rather than political. Kane himself did not seem to have approved of the wanton vandalism but war was war.[11]

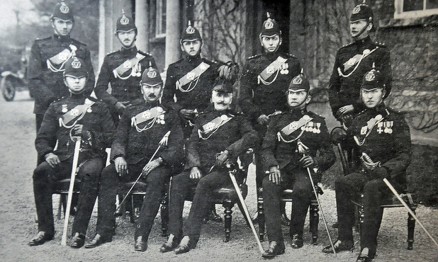

The Police Old and New

The official response was to increase police pressure. In Ballon, for example, the RIC increased their patrols to a daily basis, and were aggressive enough to threaten at gunpoint suspected Volunteers as they left Mass.[12] March 1920 saw the arrival of the Black-and-Tans into Ireland to buttress the RIC with their military experience. They were to earn a dark reputation: in one of many incidents, a group of them robbed a pub after being refused service and drove off threatening to blow the building up next time. Shots were fired over a passing civilian car on the road for good measure.[13]

Similarly, Black-and-Tans caused a scene demanding drink after-hours in a pub in Ballylinan; in the same edition of the newspaper covering this, it was reported that three RIC men had resigned, including one of three years’ service in Athy, with rumours of more to come. The RIC was a decaying force by late 1920, many of its long-standing members sloughing off and replaced by recruits of a very different temperament.[14]

In contrast, the Volunteers were thriving in the duties of an irregular police force even as the official one was forgetting its own. The Athy Battalion became the retrievers of stolen property from bicycles to timber, earning praise from the Carlow Nationalist newspaper for the “excellent manner in which they are protecting the property for the citizens.”[15] An opinion piece in the newspaper went as far as to criticise those who wanted to put “every kind of duty on to a body already overburdened by the honorary duties they have assumed.”[16]

September 1920

However excellently performed, police work was not what the Brigade had been intended for. September 1920 saw the Brigade finally stepping up its military efforts, albeit with mixed results.

Upon hearing of the Carlow DI visiting Tullow with only a driver to accompany him, a plan was hatched by the Tullow Company of the 3rd battalion to ambush him on his return route, but after two hours of waiting, the ambush team, including Daniel Byrne, was told that their target had prudently returned by a different route.[17]

Byrne was unclear in his Statement as to whether the intent was to kill, kidnap or rob the DI. The Tullow Company was able to launch an actual attack on an RIC patrol later in the month. According to Byrne, who was again involved, this was to rob the constables of their much-needed guns, though historian William Nolan was to claim that it was to kill two “particularly obnoxious” policemen.[18]

The ambushers had been forewarned that the RIC had been beefing up their security as of late, with four-strong units patrolling while armed. The advance party of the ambush also consisted of four men, with some others serving as backup. According to a witness, they numbered fifteen or more. This witness was Sergeant W. H. Warrington who provided a first-hand account of the ambush as part of his testimony at the resulting inquest.

War Comes to Tullow

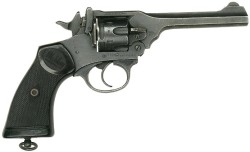

Warrington had left Tullow Barracks with Constables Patrick Halloran, Timothy Delaney and John Gaughran, the first two at the front with the other pair following, when they encountered the ambush party waiting for them. There was a cry of ‘hands up’ from one of the party while simultaneously a shot was fired at the policemen, either from nerves or intent to kill.

Warrington promptly returned fire with his revolver, and in the resulting firefight, Warrington believed that between twenty and twenty-five shots were fired, the majority by the ambush party. If the ambushers had hoped that the element of surprise would overawe the policemen into surrendering, they were mistaken.

“For God’s sake, don’t shoot!” Warrington heard Halloran cry, his arm raised. When that proved futile, Halloran joined in instead with his own revolver. Warrington saw Delaney collapse, and one of the ambushers fall, rose and fell again, indicating a wound. The attackers retreated while Warrington and Halloran hurried to the safety of their barracks, from where they were reinforced by more of their colleagues.

Gaughan was found dead, his undergarments soaked in blood, in a nearby house where he had gone for cover before haemorrhaging to death from an abdomen wound. Delaney had died where he had fallen. Both revolvers of the slain men were found not to have been discharged and had remained fully loaded. Rumour was that one of the slain policemen had been in the last week of his job, having given in his resignation.[19]

Further proof of the “mischances of guerrilla warfare,” as William Nolan put it, was how the two dead men had been well-respected and liked, even by the Volunteers, while the intended targets had escaped with only minor injuries, a view supported by Nan Nolan, who remembered some of the shooters saying afterwards that the wrong men had been shot (although she was personally unsympathetic due to a earlier bout of comparatively mild questioning in the street by Constable Delaney).[20]

A Hornet’s Nest

Byrne did not say whether the ambush party had taken the guns from the slain constables and thus could have something to show for their botched robbery, if robbery had been the primary motive. The resulting hornets’ nest astir may have made the ambush more trouble than it was worth. Two shops were burnt down in the middle of the night as a reprisal. Tullow residents heard a rifle crack, almost as if it was a signal, followed by a volley of about ten rounds in succession.

Then there was a bomb explosion, and the shop of the Murphy Brothers burst into flames, followed by the shop of William Murphy and Sons further up the road. The fire threatened to consume the rest of the street, despite the best efforts of a team of people using buckets of water, until the Carlow Fire Brigade arrived with fifty Volunteers in tow. Realising that the burning shops were lost causes, the Fire Brigade focused on containing the fire, operating the hose while the Volunteers pumped the water from the river.

Once the fires had finally died down and the damage could be assessed, it was found that in addition to the fire-gutted shops, another store had been robbed of £100 worth of goods. The damage to Tullow was more than just material: rumours of further reprisals drove almost two-thirds of the population to seek refuge in surrounding villages or country houses, making the following Friday fair the smallest on record.[21]

Numerous arrests by the RIC and British army followed, with suspects stripped to see if they had any wounds to indicate recent combat. Byrne threatened with a gun in his mouth by two constables before being released but forced to go on the run two days later upon hearing that he was still a wanted man. That was the effective end of Byrne’s time as an active combatant, for he remained a fugitive until the Treaty ten months later, and the rest of his Statement after the telling of his flight is brief.[22]

Fortune Favours the Bold?

The early months of 1921 saw another surge in Brigade activities. A flying column was formed which would be free to move through the territories of the different battalions, with the equipment necessary to take the fight to the enemy. On the 21st of April, however, the column was surprised by a Crown patrol and quickly overwhelmed with virtually all of its members captured.[23]

Shortly afterwards, on 16th of May, an RIC patrol of four constables and a sergeant were fired at while cycling towards Barrowhouse, Co Laois, the territory of the 5th battalion. No one in that battalion would submit a Statement to the BMH, and all that Kane knew of it was that two Volunteers had been killed in what he described as a “badly sited ambush”, so we are dependent on the contemporary reporting of the Carlow Nationalist, which drew on the official reports from Dublin Castle and on what local people had heard.

Upon the first shots, the RIC patrol dismounted from their bicycles and returned fire. By the time Crown reinforcements arrived, the ambushers had been driven back, leaving behind two of their own: James Lacey and William Connor. From the nature of their wounds, death was judged to have been near instantaneous, Lacey having had a wound to his side, and Connor in the neck. Of the RIC patrol, one man had been wounded.

A number of weapons discarded by the fleeing ambushers were also found on the scene. The official version of events reported the number of ambushers to have been twenty, but people in the vicinity judged them to have been five to seven based on the noise of the guns heard.

The local mood was described by the Carlow Nationalist as having been one of consternation, as well it might. Shortly afterwards, a group of ten men, undoubtedly of the Crown forces, with their faces hidden under capes, descended on Barrowhouse, interrogating members of the Lynch family as to the identities of the ambush party, before burning down their home along with a Sinn Féin hall. That another Crown patrol would arrive later to ask for descriptions of the men involved would suggest that it had been an unauthorised action, unlike the one in Tullow the year before, where the DI displayed a marked disinterest in investigating.

The bodies of Lacey and Connor were released to their families for burial, leading the Nationalist to comment on the coincidences of two men who had been of the same age (26) and born on the same day, baptised on the same day, killed on the same day and were finally to be buried on the same day. The 5th battalion may have previously won praise for its honorary police work, but as a guerrilla force it had been a miserable failure.[24]

Lesser Battles

Both the formation of the flying column and the ambush on a decently-sized RIC patrol were risky gambits by the Brigade which showed an increasing confidence and a desire to accomplish as much as possible. However, their failures showed the dangers of pitting enthusiastic amateurs against trained soldiers, with the price paid in blood and lost weaponry.

More successful for the Brigade were its lower-level forms of harassment. Blocking roads by felling trees across the road or damaging bridges was ideal in that it disrupted enemy patrols while avoiding dangerous contact with them. The men of the 3rd battalion were proficient at this type of work, managing one or two blockages a week, after learning when and where a Crown patrol was due to come by to maximise the frustration. Such activities were not always without consequences – the destruction of the bridge at Rathmore led to a big round-up and the arrest of a company captain – but it was preferable to the death or injury that a more direct form of warfare risked.[25]

Raids on mail trains or postmen during their rounds occurred throughout the early months of 1921 and up to the Truce, with authorities seemingly helpless to stop it. Such raids were done to check for any letters reporting to the RIC, with the bonus of police codes being found from one robbery. Often the mail would simply not be returned; in other cases, the letters would be returned after certain parts had been censored and marked ‘passed by the IRA’, helping to reinforce the sense that the guerrillas were one step ahead of anyone, whether the authorities or the public.[26]

The RIC barracks remained a presence as long as their garrisons did. Outside their walls the Carlow Volunteers could be brazen, such as when a military truck waiting outside Carlow Barracks was hijacked and found burnt elsewhere. But while attacks were planned on various barracks, none were carried out. Considering the past times the Brigade had bitten off more than it could chew, that was probably just as well for it.[27]

Sergeant Boyle

Attacks on RIC personnel continued, preferably if they could be caught alone and by surprise. Even so, the targets had an inconvenient tendency to shoot back.

Sergeant Boyle was shot on the 23rd of March, 1921, while riding his bicycle back to Carlow Barracks from his residence in Graiguecullen. Boyle was hit twice, high in the back and in his left jaw under the eye, and while Kane believed that it was the wearing of a chain waistcoat that saved Boyle’s life, this armour obviously would have done nothing about the latter injury.

The wounded Boyle was able to fire back, driving off his attackers, and upon being found by sympathetic passer-bys, was transferred to Dublin Military Hospital where, so the Nationalist assured its readers, he had “every hope of a speedy recovery.” Sergeant Boyle was still alive by the time Kane submitted his BMH Statement in 1957, a tribute to either the skills of the Military Hospital doctors, the precaution of a chain waistcoat or the hardiness of Boyle.[28]

James Duffy

A month later, thirty-year old Constable James Duffy, a Black-and-Tan, was walking with a friend, Harry James, when they were ambushed by three gunmen who had been waiting in a hedge. Two of them fired at Duffy, indicating that he was the primary target despite him being dressed in civilian attire, while the other fired at James, who fled despite receiving two wounds on his shoulder and hip. Duffy’s body was found to have been ridden with bullets, including one that had been fired under the chin at close-range, his assassins having left nothing to chance.

A son of a well-known horse-dealer, Duffy had served four years in the Royal Garrison Artillery in the First World War for which he had been decorated. The shooting occurred in the territory of the 1st battalion, during the time when the flying column was encamped in the same area, so the attack can be attributed to either of these two groups.

According to Kane, Duffy was shot because he was investigating the area, using James as his spy, while the fact that the two men had been returning from a pub when attacked would suggest that the relationship between the two was a social one – two ideas that are, of course, not mutually exclusive.[29]

Sergeant Farrell

The last attempt by the Brigade to strike a blow before the Truce was the shooting and wounding of Sergeant Farrell in Borris, June 1921. The task was assigned to John Hynes, the tough, hands-on Vice O/C of the 4th battalion. Farrell had been on the GHQ’s ‘black list’ for some time, as he was reputed to have been part of the murder of Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain of Cork.

Hynes received his orders on Friday evening, giving him time to assess that the best opportunity for an attempt on Farrell’s life was in the morning when he left the improvised RIC barracks at the Protestant school, where he slept, for breakfast at his home in town. Hynes selected three men to accompany him as part of the hit squad. They were only just getting into position behind a wall when Farrell came into sight.

Hynes fired at Farrell, prompting the sergeant to shoot back before running into the cover of the wall and back towards the barracks. Farrell made to the barracks’ gate before collapsing in the road from his wounds. The ambush team retreated at that stage, either because the rest of the barracks’ garrison was returning fire at this point, according to Hynes, or because of the number of people who were heading to Mass made a clear shot too difficult (according to a second-hand account). Farrell was put on a motor car by his colleagues to the hospital where he recovered.[30]

Tough at the Top

The other casualty of the Farrell shooting was the position of the 1st Battalion O/C Pierce Murphy. He was demoted by GHQ for his “conscientious objections” in refusing to give orders to shoot Farrell, an awkward virtue in a guerrilla leader.[31]

The Carlow Brigade had a high turnover of its officers, either from insufficient aggression as with Murphy, internal politics (Patrick Kane believed Brigade O/C Eamon Malone had been retired following the Truce for not being a “complaisant yes-man”) or the ever-present danger of arrest.[32]

The last point was illustrated when the 3rd battalion O/C Michael Keating had to go on the run following the slayings of Constables Delaney and Gaughran. Keating left his Vice O/C William Donohue as the replacement O/C and promoting Matthew Cullen to Vice O/C accordingly. Both Donohue and Cullen were arrested a month later, forcing another round of rapid promotions to cover them. Little wonder, then, that Kane thought dimly of the quality of the officers left by the time the Truce came.[33]

Final Thoughts

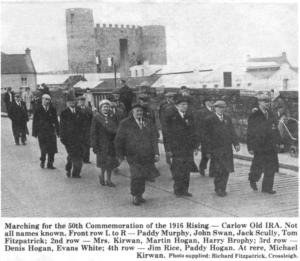

In reviewing the Carlow parishes of Ballon and Myshall during the War of Independence, Nan Nolan felt confident enough to assert that: “Other people and places may have been lucky enough to get better headlines, but any man in Ireland who had been through these two parishes during the four glorious years spoke only the best of them.”

As an example of this, Nan Nolan related how the Ballow Company blockaded the village due to the arrival of over a hundred British soldiers in June 1921. The Volunteers were mobilised at night, and did not retire home in the early hours of the morning until all the roads had been blocked with timber and the bridges destroyed, denying entrance to Ballon by anything bigger than a bicycle. It was an undeniably impressive feat on the part of the Ballon Company in the swiftness, thoroughness and secrecy of its operation.[34]

However, it is also important to note that the blockade was done after the British convoy had already left Ballow. There was no suggestion at even a consideration to confront the enemy head-on. Going by the records of other units, it is hard to imagine any such attempt resulting in anything other than a bloody loss for the Brigade.

So there is more than a touch of the ridiculous to Nolan’s suggestion that the lack of fame for Carlow compared to that for other counties during this period can be attributed to opportune headlines. Nowhere was there anything to match the more dramatic actions undertaken by the likes of the Cork or Dublin Brigades, and nothing comparable to the Kilmichael Ambush, Crossbarry, the burning of the Customs House or Bloody Sunday.

Yet, by the time of the Truce, the Carlow Brigade was still a functioning force. How well it would have continued to be so is a debatable issue: Nolan’s optimistic take can be contrasted with Patrick Kane’s shock at the quality of the remaining officers. The Brigade had fought small, and when it had tried to fight big it had lost badly. But it had fought all the same, from the start of the War to the end, and in the most important area of accomplishment, it could boast of equal status to all the others: it had survived.

Originally posted on The Irish Story (24/09/2014)

See also: Bushwhacked: The Loss of the Carlow Flying Column, April 1921

References

[1] Kane, Patrick (BMH / WS 1572), pp. 27-9

[2] Nolan, William, ‘Events in Carlow 1920-21’, Capuchin Annual 1970, p. 582

[3] Kane, p. 13

[4] Gerrard, E. (BMH / WS 348), p. 8

[5] Nolan, Willian, p. 582

[6] Nolan, Nan (BMH / WS 1441), pp. 6-7

[7] Ryan, Thomas (BMH / WS 1442), p. 10

[8] Brennan, James (BMH / WS 1102), p. 12

[9] Kane, p. 3, 6-7

[10] Nolan, Nan, pp. 11-12 ; Fitzpatrick, Michael (BMH / WS 1443), p. 6 ; McGill, John (BMH / WS 1616), p. 10

[11] Fitzpatrick, p. 2 ; Kane, p. 11

[12] Nolan, Nan, pp. 5-6

[13] Carlow Nationalist, 28/08/1920

[14] Ibid, 14/08/1920

[15] Ibid, 03/07/1920

[16] Ibid, 11/09/1920

[17] Byrne, Daniel(BMH / WS 1440), p. 3

[18] Nolan, William, p. 585

[19] Nationalist, 18/09/1920 ; McGill, p. 5

[20] Nolan, William, p. 585 ; Nolan, Nan, p. 7

[21] Nationalist, 18/09/1920

[22] Byrne, pp. 3-4 ; McGill, pp. 5-6

[23] Kane, pp. 16-18

[24] Ibid, p. 9 ; Nationalist, 21/05/1921

[25] Ibid ; McGill, pp. 6-7

[26] Ryan, p. 5 ; Nationalist, 09/07/1921, 02/05/1921

[27] Nationalist, 18/06/1921

[28] Kane, p. 16 ; Nationalist, 26/03/1921

[29] Nationalist, 09/04/1921 ; Kane, p. 16

[30] Hynes, John (BMH / WS 1496), pp. 16-7 ; Ryan, p. 9

[31] Hynes, p.17 ; Kane, p. 9

[32] Kane, p. 21

[33] Ibid, p. 22 ; McGill, p. 6

[34] Nolan, Nan, pp. 11-12

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History / Witness Statements

Brennan, James, WS 1102

Byrne, Daniel, WS 1440

Fitzpatrick, Michael, WS 1443

Gerrard, E., WS 348

Hynes, John, WS 1496

Kane, Patrick, WS 1572

McGill, John, WS 1616

Nolan, Nan, WS 1441

Ryan, Thomas, WS 1442

Article

Nolan, William, ‘Events in Carlow 1920-21’, Capuchin Annual 1970

Newspaper

Carlow Nationalist