One possible lesson to take from this book is that politics is something best left to politicians. Shortly after the 1957 electoral defeat of John A. Costello’s second and final coalition government, the former Taoiseach was walking along the Dublin quays with two other senior Fine Gael men, James Dillon and Patrick Lindsay.

One possible lesson to take from this book is that politics is something best left to politicians. Shortly after the 1957 electoral defeat of John A. Costello’s second and final coalition government, the former Taoiseach was walking along the Dublin quays with two other senior Fine Gael men, James Dillon and Patrick Lindsay.

As they passed a pub, Dillon remarked about how he had never been in one except his own which he had sold after observing how much money his customers were spending which could have gone instead into family essentials. Costello chipped in with a story of the one time he had been in a pub when a bottle of orange juice had almost been too much for him.

To the worldlier Lindsay, the pub was “the countryman’s club, where everything is discussed and where contacts are made.” The exchange he had witnessed told him all too much as to why Fine Gael “are going in this direction today and why we are out of touch with the people.”

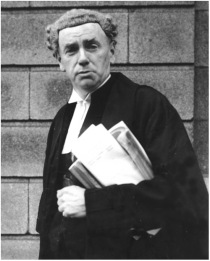

Also telling was Costello’s subsequent performance as a part-time leader of the opposition. An exceptionally gifted barrister, his success at attracting briefs in Cork – no small achievement for the Dubliner Costello, given how hard it was for outsiders to break into its insular legal world – led to him dividing his time between court hearings there and Dáil attendance in Dublin. Costello was obliged to travel to Cork on one Sunday evening and then return to Dublin on Wednesday evening for a Budget vote before returning to Cork early on Thursday morning.

It was an impressive display of time management – when it could be done. At other times, Costello was forced to prioritise one duty over another, such as when he spent three weeks in Cork with the High Court at the expense of two weeks of Dáil sittings. His party followed his example. Attendance of Fine Gael TDs was poor, and those present often preferred to read quietly or talk amongst themselves. Fianna Fáil could not have asked for a more obliging opposition.

If any study of Fianna Fáil can equate to a study of 20th Irish politics, given the sheer regularity of the party in power (only time will tell if its current malaise will prove to be a passing phase or a more lasting decline), then, by that same token, a look at Ireland’s also-rans can give an insight into what not to do.

While it would be simplistic to attribute Fine Gael’s problems to a reticence towards having a pint or two, its leaders have displayed a remarkably consistency over the years in not missing an opportunity to miss an opportunity. Enda Kenny’s snatching of defeat from the jaws of victory following his inept 2007 debate with Bertie Ahern, and Alan Duke’s high-minded-but-disastrous ‘Tallaght Strategy’ are two examples that spring to mind.

As the title to McCullagh’s book suggests, Costello was an unusual choice for the top job but then, the 1948 general election produced an unusual government, being an alliance of ‘everyone but Fianna Fáil’. Due to his record of executions during the Civil War, Fine Gael leader Richard Mulcahy was an unacceptable choice for Taoiseach but Labour and Clann na Poblachta were supportive of Costello as a compromise candidate, thanks in no small part to his friendship with leading figures in both parties.

The man of the hour was oblivious to the discussions being made on his behalf and was not pleased when the offer was broached to him. Costello’s aversion stemmed in part to financial considerations. With a family to support, he was reluctant to put aside the money he was making at the Bar for the uncertainty of politics. But his main concern, as he confided to his son and with a humility rarely found in politics, was his lack of self-confidence and the “fear amounting almost to terror that I would be a flop as Taoiseach.”

When his suggested alternatives were brushed away by his colleagues, and faced with their unanimous support (not something every prospective leader can claim), Costello finally gave in. Never one to let things get to his head, Costello responded to the rapturous ovation at the following Fine Gael meeting by pointing at Mulcahy and saying: “This is the man you should be applauding, not me.”

Compared to the likes of Éamon de Valera, who had only to look within his heart to know what the Irish people wanted, or Charles Haughey (enough said), such humility makes for a refreshing change. The question remained, however, as to whether, to steal a phrase from Winston Churchill, the new Taoiseach would have much to be humble about.

The first Inter-Party Government has largely been remembered for two of its initiatives: the Mother and Child Scheme and the 1948 declaration of the Irish Republic. McCullagh treats his subject’s role in both sympathetically but not uncritically.

If Costello was obsequious in his deference to the Church then, as McCullagh reminds us, that was to be entirely expected in those pre-Father Ted times. As for the repeal of the External Relations Act, it finally put paid to a long-standing ambiguity – was Ireland in the Commonwealth or not? – but the abruptness with which Costello announced it and his unnecessarily defensive manner did him no favours.

Costello’s government fell apart by the bare minimum of Dáil seats when a handful of Independent TDs were wooed over to Fianna Fáil. As part of the new cost-cutting policies under Éamon de Valera, Costello lost his state car. A measure of the man can be gauged by how he allowed de Valera to not only keep his when the roles were reversed a couple of years later and it was Fianna Fáil’s turn on the Opposition benches but also the insurance on the exact same terms as before.

The two years before Costello’s return to office was perhaps the highlight of his dual careers as barrister and politician. As the former, Costello defended The Leader journal against the libel suit by the poet Patrick Kavanagh. Costello’s victory for his client after the devastating cross-examination against Kavanagh on the stand did not deter the two from becoming friends.

The Kavanagh case is one of the few times McCullagh detours into Costello’s legal work. Charles Lysaght has criticised the book in the Irish Independent for this abridgement, pointing out how Costello had been Ireland’s leading barrister in the 1930s to the early ‘50s. But then, how many readers would be as interested in Costello the lawyer as they would be in Costello the statesman?

On the public stage, Costello was able to hammer away at his enemies’ austerity measures (as popular then as today) until a succession of by-election defeats for the government forced a general election. That the outgoing Fianna Fáil administration had been briefer than Costello’s (who was not above highlighting such a fact) was sweet vindication against those who had griped that such a hybrid as a coalition government could never last.

But gaining power is not the same as handling it. The economic gloom deepened, prompting a reverse situation from before, with the Inter-Party Government losing ground through lost by-elections. Already depressed by the death of his wife, Costello adopted an increasingly impervious note: “I have had so many disappointments that one more does not make any difference.”

The one that did was the use of the Irish Army and Gardai against resurgent IRA violence along the Border. The staunchly Republican Clann na Poblachta, who had been propping up the government as before, responded with a vote of no confidence.

Ironies abounded. Costello had always despised Partition to the point of being rude to some hapless RUC officers who were rescuing his car from a flooded road while he was on holiday in the North. Seán MacBride had initially demurred from the censure motion until pressure from his party forced his hand. He feared that a rebounding De Valera would be even harder on the IRA – which, of course, he was. McCullaugh quotes one Republican activist who was interned throughout the subsequent Fianna Fáil administration that at least under Costello he had been assured of a fair trial.

With no choice but to call a general election, Costello kept a brave face amidst the crushing defeat, with the Soldiers of Destiny snagging 78 out of the 147 seats on offer. McCullagh is brutally frank about the scale of Fine Gael’s disaster and Costello’s lacklustre leadership when back in opposition but he makes the case that many of the initiatives Seán Lemass would be celebrated for – the economic revival and his glasnost towards the North – had had their roots under Costello.

This book is well-written, flowing smoothly from one subject to another. The research is impeccable, allowing readers to gain a strong sense of the times as well as of the players involved. The central one here is, of course, Costello, managing his colleagues with skill, events perhaps less so. Costello was suited more to the private life of a barrister than a public one as a politician. Yet he was able to succeed at both and his dual terms as Taoiseach, regardless of his fears, left an enduring mark on Irish politics.

Publisher’s Website: Gill & MacMillan, Limited

Judging W.T. Cosgrave is the third in the Judging X series and the first to be on a non-Fianna Fáil figure, the previous two being about Éamon de Valera and Seán Lemass. The book launch was notable in the presence of the Taoiseach, Enda Kenny; likewise, the one for Judging Dev in 2007 was attended by Bertie Ahern: statements in themselves about how Civil War politics continues to define the contemporary sort in Ireland. It is hard, after all, to imagine either of the two party leaders ‘crossing the floor’ by attending the other book launch. Cosgrave, de Valera and Lemass may be long dead, but the ghosts of their wars continue to be felt today.

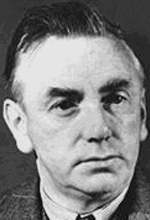

Judging W.T. Cosgrave is the third in the Judging X series and the first to be on a non-Fianna Fáil figure, the previous two being about Éamon de Valera and Seán Lemass. The book launch was notable in the presence of the Taoiseach, Enda Kenny; likewise, the one for Judging Dev in 2007 was attended by Bertie Ahern: statements in themselves about how Civil War politics continues to define the contemporary sort in Ireland. It is hard, after all, to imagine either of the two party leaders ‘crossing the floor’ by attending the other book launch. Cosgrave, de Valera and Lemass may be long dead, but the ghosts of their wars continue to be felt today. Such mild appearances were deceiving. Upon the sudden deaths of Arthur Griffith and Collins in 1922, the newly-chosen Chairman of the Free State Cabinet found himself with the unenviable task of heading a government under siege. His enemies were initially contemptuous: de Valera dismissed him as a “ninny”, while Rory O’Connor courted hubris in believing that Cosgrave could be “easily scared to clear out.”

Such mild appearances were deceiving. Upon the sudden deaths of Arthur Griffith and Collins in 1922, the newly-chosen Chairman of the Free State Cabinet found himself with the unenviable task of heading a government under siege. His enemies were initially contemptuous: de Valera dismissed him as a “ninny”, while Rory O’Connor courted hubris in believing that Cosgrave could be “easily scared to clear out.”

Other choices on symbols are all too illuminating: the official seal of state would be a harp but not one, God forbid, with a female figure included. Catholic morality was the order of the day. Cosgrave saw to it that the new coinage would feature only ‘profane’ images, as opposed to religious ones, given the worldly ways money could be used. This was still too much for one priest who ruminated against the coins as “the thin edge of the wedge of Freemasonry sunk into the very life of our Catholicity.” Quite.

Other choices on symbols are all too illuminating: the official seal of state would be a harp but not one, God forbid, with a female figure included. Catholic morality was the order of the day. Cosgrave saw to it that the new coinage would feature only ‘profane’ images, as opposed to religious ones, given the worldly ways money could be used. This was still too much for one priest who ruminated against the coins as “the thin edge of the wedge of Freemasonry sunk into the very life of our Catholicity.” Quite.