Two Events, One Day

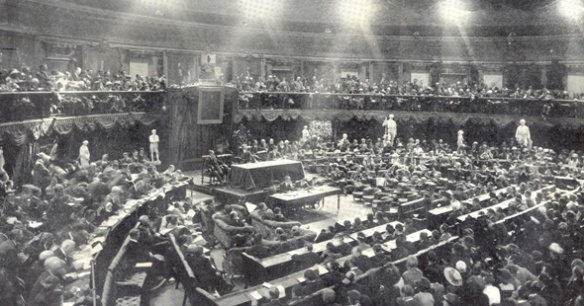

Curiously, the fact that two of the most important events in Ireland for the year 1919 – and arguably for this period in Irish history in general – happened on the same day is, if not quite unconnected, a coincidence. IRISH REPUBLICAN “PARLIAMENT” – FIRST MEETING IN DUBLIN – REMARKABLE GATHERING went one set of headlines in the Irish Times for the 22nd January, covering the events of the day before. Elsewhere in the same edition of that newspaper were TWO POLICEMEN MURDERED – SHOT DEAD BY MASKED MEN – THE DEAD MEN’S RIFLES STOLEN – TIPPERARY TO BE PROCLAIMED A SPECIAL MILITARY AREA.

As the quote marks around the word ‘Parliament’ indicate, the Irish Times, long a mouthpiece for genteel opinion, did not take that seditious congress on the 21st entirely seriously. This was despite the attendees all being Members of Parliament (MPs), elected only a month previously in the General Election of December 1918, albeit on a strictly abstentionist basis as per the policy of the Sinn Féin party – which was where the innovation lay. If the freshly-minted MPs were not to go to the Parliament of Westminster, then a parliament of their own, it seemed, they would go.

“There have been many remarkable assemblies in the spacious Round Room of the Dublin Mansion House from time to time,” the newspaper read, “but that which opened its proceedings yesterday afternoon at 3.30 o’clock possessed many characteristics which rendered it unique.”[1]

For others, however, this was more than a novelty but something profound and very, very serious. “No day that ever dawned in Ireland had been waited for, worked for, suffered for like the Tuesday in January 1919 when the First Dáil Éireann met,” wrote Máire Comerford. She had been one of the many Sinn Féin activists doing the waiting, working and suffering since the Rising of 1916, almost two years before. For her, this had all been about more than a single election, more than a transfer of power and responsibility from one party to another – “the responsibility to vindicate the men of Easter Week was on our shoulders” – and now, at last, vindication seemed to have come about.

“If Robert Emmet could be here with us,” Comerford overheard someone say in the crowd of onlookers that curled from the front of the Mansion House, all the way to Kildare Street. “Ah, he is not far away,” came the reply. No doubt the pair had the aforementioned martyr’s famous epitaph, about it not being written until my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, in mind.[2]

For this was exactly what the occupants in the Round Room that afternoon intended to make happen. “The fundamental principle of Sinn Féin was not to ask others, particularly the Conquerors, to concede us our freedom,” explained another party worker, Kevin O’Shiel, “but…to go forth boldly and proclaim it.”[3]

That they did. When it was time to begin, at 3:30 pm, the Sinn Féin MPs – or Teachtaí Dála (TDs) if one prefers – of An Dáil Éireann slowly filed in, up the centre of the hall. Of the sixty-nine elected in the General Election, only twenty-seven were present, the others being currently in jail, another sign that the times were far from normal or settled. At the head of the procession were Count Plunkett and Eoin MacNeill, and anyone familiar with Irish politics would have recognised this pair, the two most senior members of Sinn Féin still at liberty. But it was a relative unknown, Cathal Brugha, who served as Chairman for the proceedings – the Irish Times was not even sure of his name.

“Mr Burgess is a young man of athletic build and strong features,” explained the newspaper in the briefest of summaries, “and he played a prominent part in the rebellion of 1916, when he was severely wounded” – which may not have seemed much of a political career so far in itself, but in the new Ireland, any connection with the Easter Rising of blessed memory was sufficient. Despite being a relative neophyte in public affairs, Brugha rose to the occasion, according to Piaras Béaslaí. In addition to being TD for Kerry East, Béaslaí had been among those helping behind the scenes, drafting the documents to be presented and, in this case, picking the right man for the role.[4]

“It was my suggestion that Cathal Brugha should preside,” Béaslaí wrote in his memoirs, “and it proved a very happy decision” as he “presided over the assembly with solemn dignity.”[5]

Proclaiming Freedom

All the attending representatives were from Sinn Féin, making this more of a Sinn Féin event than an Irish parliament per se. Other winning candidates in the General Election had been invited but the remaining MPs of the all-but-defunct Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) were absent, as were the Ulster Unionist. Not that anyone had expected anything from the latter group; indeed, the only ripples of laughter in the otherwise sober proceedings were when Edward Carson’s name was read out in the roll-call.

Still, as Sinn Féin had won the lion’s share of electoral seats, the party gathering in the Mansion House that day could be considered a national one by default. This uniformity in the room helped the inauguration of Dáil Éireann to go smoothly enough, despite its shortfall in members present. Four motions were proposed in the course of the event and all passed without debate or fuss:

- The Provisional Constitution.

- Declaration of Independence.

- Appointment of delegates to the Versailles Peace Conference.

- The Democratic Programme.[6]

As each reveals something about the context of the time, and the goals of the new assembly, it is worthwhile exploring them in some depth.

The Provisional Constitution:

This first was largely a work of necessity – “based on practical common sense,” as Béaslaí put it – establishing as it did an Executive or Ministry of five, headed by the President – someone has to be in charge, after all, even in a free nation.

The roles of the various Ministers matched the needs at hand: a Minister of Home Affairs for administration, a Minister of Finance for money matters, and a Minister of Defence to take responsibility of the Irish Volunteers. That armed body had been marching in lockstep with Sinn Féin since the Easter Rising, throwing its energies into the latter’s election campaigns, and so it was assumed the Volunteers “would, in accordance with the principles of their constitution, accept the authority of a Parliament freely elected by the people of Ireland” (it remained to be seen if things would go quite as easily as all that). Last and most definitely least, in Béaslaí’s eyes, was the fifth position in the Executive: the Minister of Foreign Affairs, which “was, of course, only an ornamental , and intended chiefly as a gesture indicating our claim to international status.”

And that was that for now. This new ruling board was a concise one as “it would have been absurd, out of the small number of members at liberty, to appoint a larger Executive,” though this would only be the start, as its size grew in time to accommodate its responsibilities.[7]

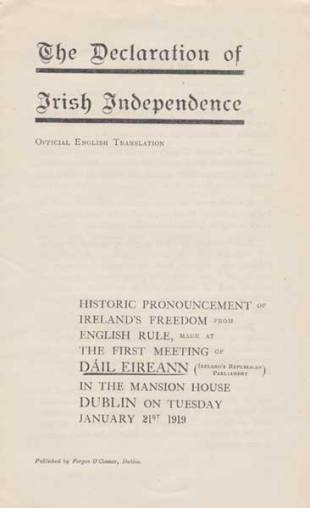

Declaration of Independence:

Considering the purpose of the Dáil and that of Sinn Féin in general, it was hardly unexpected that something of this nature would be made, and so the reading of it was “praiseworthily brief,” according to a grateful O’Shiel:

The essence of that document…was that having recalled that the Irish Republic was proclaimed in Dublin on Easter Monday, 1916, it went on to say that ‘Now therefore we, the elected Representatives of the ancient Irish people in National Parliament, do, in the name of the Irish nation, ratify the establishment of the Irish Republic and pledge ourselves and our people to make this declaration effective by every means at our command.’[8]

Perhaps because the ‘Declaration of Independence’ was self-consciously following in the footsteps of 1916’s ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’, it has been destined to stay in its shadow – during the Decade of Centenaries, it was copies of the latter, not the former, that were delivered to every school in the Republic in 2016. Or possibly this is due to the ‘Declaration’ lacking the literary quality of the 1916 Proclamation, which enjoyed the input of no less than three talented writers: Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh and James Connolly, as noted by Daniel Mulhall, then Ambassador to the United States.

“The Declaration is best seen perhaps as a reiteration of the 1916 Proclamation,” Mulhall writes:

The difference between the two documents is the context in which they were issued. When it occurred, the Easter Rising expressed the will of a relatively small minority of Irish nationalists, whereas in January 1919 the members of the First Dáil had the wind in their sails in the wake of that decisive election result a month before. The quest for some form of independence now had the undoubted support of a majority of the Irish electorate.[9]

As the 1916 Proclamation had been an avowedly Republican declaration, what else could the new state be? ‘The Irish Republic’ was to be its name in English, with Saorstát Éireann for the Irish version. The IPP had exhausted itself for the futile sake of Home Rule only six years before; now, anything short of complete separation from Britain was unacceptable. All the same, even some at the forefront of the struggle would wonder if the new parliament had not been a little hasty.

Upon reading the news in Durham Gaol, Darrell Figgis fretted that the Dáil was putting the cart before the horse, for to declare a Republic before the Versailles Peace Conference would drastically lessen the chances of the Irish delegates being received for fear of Britain taking offence. And P.S. O’Hegarty later traced the seeds of the Civil War, the disaster-to-come, to his colleagues aiming too high to soon. “Up the Republic! was a fine slogan. The Republic itself was a fine objective,” he wrote in 1952, a sadder and maybe wiser man. “But it was plainly unattainable and it became a ‘strait-jacket’ not alone for de Valera but for everybody else.”[10]

But that was for the future to worry about. Whatever may be said for the prudence or literary qualities of the ‘Declaration’, it announced its message well enough: Irish independence was here to stay.

Helping Those Who Help Themselves

Appointment of delegates to the Peace Conference

That the Peace Conference, due to meet in Versailles, Paris, would provide the stage for Ireland to be embraced by the sovereign states present as one of their own had long been a cornerstone of Sinn Féin policy. Indeed, Seán T. O’Kelly, one of the organisers of the Dáil’s inauguration, remembered the haste and anxiety to get things done before the Peace Conference, which may explain why the date for January, so soon after the General Election, was chosen.[11]

President Éamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith and Count Plunkett were appointed as the three delegates, a fact surely complicated by how the first two were currently in prison. But these were heady times for the Republican activists, flushed with electoral victory, to whom no problem seemed insurmountable. “It was impossible for youth, my age group then, to see how our request could be refused in the atmosphere of the time,” recalled Comerford, “when we believed that tyranny had been roundly defeated by great and generous powers like the USA, fighting for small nations.”[12]

Not that those present in the Mansion House that day were staking all their hopes on the greatness and generosity of said powers. Pádraic Ó Máille, TD for Galway Connemara, who had been the one to propose the trio, quoted as he did so the old proverb, “God helps those who help themselves.” If the Peace Conference failed to do justice to Ireland, Ó Máille added, the people of Ireland would insist themselves on justice being done.[13]

Democratic Programme

In contrast to the comforting familiarity of the ‘Declaration of Independence’, the ‘Democratic Programme’ was entering new territory – a little too much so for some. Its declaration that national sovereignty extended “to all its material possessions, the National’s soil and all the wealth-producing processes within the Nation,” with private property to be “subordinated to the public right and welfare,” makes the ‘Programme’, in Ambassador Mulhall’s words, “a strikingly radical document, echoing the kind of socio-economic concerns that had motivated 1916 leader James Connolly.”

Regardless of such merits, none of the Sinn Féin sub-committee members tasked with drafting the various documents for the First Dáil Éireann seemed to have been very excited about this particular one. Seán T. O’Kelly was to claim authorship for its final draft but only after the rest of the sub-committee had failed to come up with anything at their Harcourt Street meeting on the 20th January, the night before the Dáil was due to open. Harry Boland had come in with a loose assortment of handwritten notes which he said were from Thomas Johnson and William O’Brien, two leading figures in the Irish Labour Party.

“Boland read out these notes,” O’Kelly recalled, “and this started a long and sometimes heated discussion. There were ideas and statements which some of the committee would not accept.” O’Kelly ended up taking the bundle of sheets home, where he managed to finish the final draft by 4 in the morning, aided by no one else but his wife:

I used as much as I could of the notes given to Harry Boland by his two friends [Johnson and O’Brien]. I also used other notes and suggestions handed to me by the committee. The draft as put to the Dáil and adopted was my composition, whether it be considered good or bad.[14]

The result was the “very radical and highly dubious ‘Democratic Programme’,” as O’Shiel described with a sniff, “that, in the course of time was discreetly dropped and forgotten about.” Other contemporaries likewise hastened to disown it and its implications. “It is doubtful whether a majority of the members would have voted for it, without amendment, had there been any immediate prospect of putting it into force,” Béaslaí told his readers. “If any charge of insincerity could be made against this first Dáil it would be on this score.”[15]

The Other Thing That Happened That Day

The First Dáil took no more than two hours before adjourning at 5:30 pm. For a relatively concise affair, much had been achieved: Ireland now had a parliament of its own – albeit a self-proclaimed one – along with a government in the form of the Executive and even the start of a foreign policy. Notably, nowhere in the speeches or resolutions passed was the possibility of war mentioned even though, according to some, that was the state Ireland already was in – or should be. Ó Máille had spoken of the Irish people taking it upon themselves that justice be done; in another part of the country, earlier that same morning, others had taken matters into their own hands in quite a different way.

Constables McDonnell and O’Connell had been escorting a cartload of gelignite from Tipperary town to Soloheadbeg quarry, three miles away, while accompanied by two others: Patrick Flynn, an employee of the Tipperary County Council, and the cart driver, James Godfrey. A little after midday, between 12:30 and 13:00, the otherwise uneventful journey was interrupted by a band of masked assailants who jumped over the roadside fence, shouting at the policemen to put their hands up.

“Almost at the same moment,” Flynn relayed afterwards:

I heard a report, and the two constables fell on the road. One of the men got into the cart, and drove away in the direction of the quarry with the gelignite. The others took the policemen’s rifles and ammunition from them, and went away in a different direction. I came back to Tipperary to report the matter to the police barracks.

A doctor was brought to the scene but in vain: by then, both Constables McDonnell – 50 years old, a widower with several children – and O’Connell – 30, unmarried – were dead, the first two fatalities in what would become known as the Irish War of Independence, the Tan War or the Anglo-Irish War. Despite armed with rifles at the time, neither McDonnell nor O’Connell had had a chance to defend themselves as, according to Flynn, “the whole thing occurred in a minute or two.”[16]

Not so, argued some of the participants, years later. “The police did try to fight,” insisted Séumas Robinson, O/C of the Third (South) Tipperary Brigade, underlining the word in his text. In this version, he and another man had been grabbing the cart-reins when the two constables raised their rifles in their direction, fingers on the triggers, prompting the rest of the Irish Volunteers to open fire with the fatal shots. Another participant, the soon-to-be-famous Dan Breen, was to tell much the same, that the policemen had left their killers no choice: “We would have preferred to avoid bloodshed; but they were inflexible…It was a matter of our lives or theirs” – a statement somewhat at odds with another of his, that his only regret was that more ‘peelers’ were not present that day to meet the same fate as that would have made a stronger impression.[17]

Either way, the exact circumstances behind Soloheadbeg are perhaps less important than the fact it happened at all and why.

Neither Robinson nor Breen cared much for the other. To Robinson, the other man was a hot-headed liability, while Breen depicted his O/C in his memoirs as a clueless rube selected for his role to be a convenient figurehead. But the two were in agreement on one thing: that the Soloheadbeg ambush happened not because of the election of Sinn Féin and the forming of the Dáil but despite of it all.[18]

Turning a Blind Eye

“The public did not clearly realise the difference between the political body, Sinn Féin, and the military organisation, the Irish Volunteers,” Breen explained. The growths of the two bodies, despite their different natures, had been mirroring each other, at times overlapping – as Sinn Féin clubs were formed in various parishes, the local Volunteers would enrol as well, with the club president, as likely as not, doubling as an officer in the Volunteers. Which became, as far as Breen was concerned, a serious hindrance: “The Volunteers were in great danger of becoming merely a politic adjunct of the Sinn Féin organisation.” Simply waiting around in between bouts of time spent in jail on one charge or another was not going to accomplish anything, at least not in the way Breen wanted.[19]

Robinson also observed with dismay the stupefying effect politics was having on the military aspect of the struggle. The upcoming establishment of the Dáil in Dublin only threatened to make things worse:

We all heartily desired the formation of a Republican government, but what I feared was that the Government, once formed, being our moral superiors, a state of stalemate would be inevitable unless war was begun before the Dáil could take over responsibility. Who could, for example, expect a government situated as the Dáil would be ever to make a formal declaration of war?

If a war was not to be formally declared, then the trick would be for someone like Robinson to make one happen anyway.

News in late December 1918 of the gelignite due for transportation to Soloheadbeg thus provided him and the rest of the South Tipperary Brigade with the perfect opportunity. As he prepared for the ambush in the preceding weeks, Robinson refrained from reading newspapers or any official dispatches from the Volunteer Headquarters in Dublin, lest he learn of the Dáil’s announcement and thus lose any chance at plausible deniability, a strategic ignorance he compared to Horatio Nelson’s famous holding of the telescope to his blind eye. That the gelignite set forth on the same day as the Dáil’s opening was to Robinson mere chance, not to mention a narrow dodge – “just in time,” as he put it.

Though both Robinson and Breen were to omit the other’s responsibility in the decision to rob the gelignite and, if necessary, kill the police escort, the fundamentals in each man’s account were the same: the ambush was envisioned as the start of something bigger, and the political movement that Dáil Éireann represented seen not so much of a complement as a competitor to their efforts.[20]

“The military mind is the same in every country,” Arthur Griffith ruefully remarked when P.S. O’Hegarty told him of a planned operation by the Volunteers that was, in the latter’s opinion (and evidently the former’s as well), “fiendish and devilish and inadvisable from any point of view.” Breen, on the other hand, came to resent how “neither then [Soloheadbeg] nor at any later stage did Dáil Éireann accept responsibility for the war against the British,” leaving him and his comrades to risk their lives and liberty on the streets and fields of Ireland with scarcely an acknowledgement. Two different viewpoints, two sides in the same cause, and they could not have been further apart.[21]

References

[1] Irish Times, 22/12/1919

[2] Comerford, Máire (ed. by Dully, Hilary) On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2021), pp. 94, 98

[3] O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770, Part 6), p. 92

[4] Irish Times, 22/12/1919

[5] Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland, Volume I (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008), pp. 165-6

[6] Irish Times, 22/12/1919

[7] Béaslaí, p. 166

[8] O’Shiel, p. 94

[9] Mulhall, Daniel, ‘Blog by Ambassador Mulhall on the First Dáil, 21st January 1919’, Department of Foreign Affairs (Accessed on 15th August 2023)

[10] Figgis, Darrell. Recollections of the Irish War (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1927]), pp. 231, 235-6 ; O’Hegarty, P.S. A History of Ireland under the Union: 1801-1922 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1952), pp. 729-30

[11] Irish Press, 26/07/1961

[12] Comerford, p. 101

[13] Irish Times, 22/12/1919

[14] Irish Press, 27/07/1961

[15] O’Shiel, p. 94 ; Béaslaí, p. 167

[16] Irish Times, 22/12/1919

[17] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), pp. 29, 72 ; Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), pp. 32, 34

[18] Robinson, p. 28 ; Breen, pp. 21-2

[19] Breen, pp. 29, 31

[20] Robinson, pp. 70-2

[21] O’Hegarty, P. S. The Victory of Sinn Féin (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2010), p. 32 ; Breen, p. 94

Bibliography

Newspapers

Irish Press

Irish Times

Books

Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008)

Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010)

Comerford, Máire (ed. by Dully, Hilary) On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2021)

Figgis, Darrell. Recollections of the Irish War (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1927)

O’Hegarty, P.S. A History of Ireland under the Union: 1801-1922 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1952)

O’Hegarty, P.S. The Victory of Sinn Féin (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2010)

Bureau of Military History Statements

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

Robinson, Séumas, WS 1721

Online Article

Mulhall, Daniel, ‘Blog by Ambassador Mulhall on the First Dáil, 21st January 1919’, Department of Foreign Affairs