Power Games

James O’Neill and money mixed perhaps a little too well together; at least, that was the verdict of Frank Robbins. Despite a shared membership in the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), which had seen both men ‘out’ during the Easter Week of 1916, Robbins did not spare his former colleague his pen when it came to writing his memoirs, years later. Replacing James Connolly as Commandant of the ICA was going to be a tough sell for anyone but, in Robbins’ view, O’Neill bore particular responsibility for the post-Rising lethargy that afflicted the once-proud organisation:

His failure was entirely due to his lack of desire or ability to pursue the Connolly philosophy. When questions of policy arose O’Neill’s attitude was to procrastinate rather than take the line which would have been laid down by Connolly or [Michael] Mallin, were either there to lead.

Robbins did his best to push the ‘Connolly philosophy’ during his time on the ICA Army Council in 1918, which for him meant closer contact with the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in the latter’s insurgency against British rule in Ireland. This prospect alarmed other members of the Army Council, who feared cooperation would result in the assimilation and subordination of the ICA to the larger body. Though Robbins privately conceded there were some reasonable grounds for this concern, he pushed on regardless and managed to obtain the official sanction of the Army Council.

Robbins accordingly arranged a get-together in Liberty Hall, Dublin, between Séumas Robinson, Archie Heron and Frank McCabe, representing the IRA, and the ICA in the form of himself, Michael Donnelly (the then Secretary to the Army Council) and Michael Kelly. This meeting of minds went well enough, in Robbins’ view, as did subsequent others, but, before a deal could be reached, another election was held for the Army Council, in which Robbins lost his seat. That effectively cut the outreach effort off at the knees.

Too late did Robbins realise he had been undermined the whole time: “It was subtly suggested that…Michael Donnelly and a few others, including myself, were ‘sore-heads’” or troublesome malcontents.

A Cold Dish

As for the Iago behind these smears, Robbins knew who to blame, for they bore the hallmarks of his own Commandant. O’Neill’s “methods of controlling power were remarkably subtle,” aided by a smooth and persuasive manner:

He had an answer for every question raised and was a most convincing talker. A whispering campaign was a favourite device – you were a “very decent fellow” but “off balance in thought” – and so with a glib tongue he always went his way. When challenged at the many meetings held from time to time on matters affecting his authority he would deny that the allegations were correct and his denial would be buttressed by evidence purporting to come from “a high officer in the Volunteers [IRA] to whom he had spoken only a day or two before.[1]

When it was O’Neill’s turn to fall from grace, Robbins made sure to record it in merciless detail. He had been speaking with Seán Russell, an old acquaintance from their shared days in prison and now a member of the IRA GHQ. Russell was thus in a position to correct Robbins on a couple of misconceptions: that (1) O’Neill was also on the IRA Headquarters Staff when, in fact, he was not, and (2) twelve rifles supposedly gifted to the South Tipperary IRA Brigade on behalf of the ICA had really been bought from O’Neill.

Taken aback by these discoveries – and, one suspects, sensing an opportunity for some payback – Robbins had Russell obtain for him a written statement from the IRA Quartermaster-General, Seán McMahon, confirming the sale of the twelve rifles. Armed with this proof of financial impropriety, Robbins arranged for a special session of the ICA Army Council, where O’Neill, his way of words evidently failing him, was stripped of his rank as Commandant.

“So my labour on this very distasteful subject ended,” Robbins wrote.

But he could not resist a final kick at O’Neill’s prone reputation. A court-martial was set up to try O’Neill – demotion not being enough – during which he was also hit with charges of a criminal nature by the Dublin civil authorities and imprisoned, sometime after the Truce in July 1921. Plans from within the ICA to free their former Commandant were thwarted by Robbins, with the help of Michael Collins. When Collins wanted to go further and arrest everyone involved in the stymied rescue effort, Robbins intervened on their behalf, arguing that they had simply been acting out of misplaced loyalty to O’Neill. Collins acquiesced and Robbins left satisfied, having had his way on both accounts.

“Need I say that O’Neill was not rescued the next day,” he wrote – revenge truly is a dish best served cold.[2]

An Act with a Political Purpose?

Which is not to say that everything Robbins told should be taken at face value; his, after all, is just one voice among many from the era. Furthermore, he was “a controversial figure within the [Labour] movement,” according to his entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, who “wrote many provocative articles for the press and was known for his obstinacy at meetings” – a man, it seems, who could nurse a grudge.[3]

Fortunately, then, we are not dependent on his word for the abrupt end of O’Neill’s time as ICA Commandant. Robbins was unspecific about the nature of the criminal charges against O’Neill but contemporary newspapers and internal IRA documents do shed more light on the matter. O’Neill’s arrest in mid-1921 and subsequent detainment presented an awkward situation and not just for the man himself, touching as it did unresolved issues between the ICA and the IRA.

Though Robbins was to depict O’Neill as having no interest in contributing to the wider revolutionary movement in Ireland – indeed, being quite resistant to the idea – that is not quite the full picture. O’Neill, according to Catherine Rooney, was behind some smuggling she did of gelignite from Glasgow to Dublin, via Belfast, in 1918. “Years afterwards, I heard that that was an arrangement between James O’Neill and Joe O’Reilly,” Rooney recounted of her time in Cumann na mBan. Since O’Reilly was a top aide to Collins, it is reasonable to believe that at least some of the gelignite went to the IRA.[4]

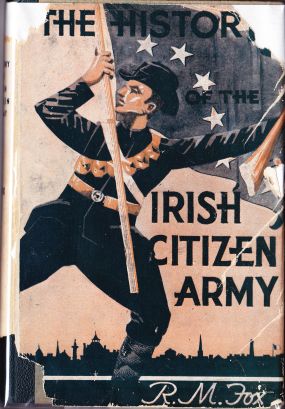

Furthermore, O’Neill and another ICA man, Michael McCormack, had on at least one occasion met Collins and Cathal Brugha in person, during which both parties agreed to assist each other, while keeping their respective armies separate and distinct. This is, at least, according to historian R.M. Fox, who had the advantages of access to ICA members and original records for his research. The image Fox provides is admittedly on the sanitised side, saying only that “O’Neill retained the position of Commandant from 1917 to 1921” without comment or expansion on how it ended, but he does present a counterbalance to Robbins’ unrelentingly hostile depiction of the ICA leader.[5]

The main thrust of Robbins’ account and allegations are, however, corroborated by contemporary correspondence – to an extent.

Sometime in mid-June 1921, the ICA Army Council received word about “a quantity of stuff from abroad” – quite likely gelignite again – that could be purchased. Request for funds from the IRA GHQ fell through due to poor communication, as did an appointment by O’Neill to meet the Minister of Finance to Dáil Éireann – Collins, it seems, did not turn up. With time a-wasting, “we had to raise the money immediately and on our own,” explained John Byrne, the Honorary Secretary of the Army Council, in a letter to Brugha, the Minister of Defence. This was by done with a robbery at Bolands Mill on the Grand Canal Dock, Dublin, on the night of the 25th June 1921.

No violence was performed in the course of this act, at least to hear Byrne tell it; indeed, it sounded like an almost civilised affair, with the cashier pointing out which box to take. When asked if the money was to be paid back, the participants assured the cashier that this would indeed be the case. Around £700 was netted, two hundred of which being put aside to pay for the ‘stuff’.

“We trust that this statement will prove to your satisfaction that this was an act with a political purpose,” wrote Byrne. O’Neill found himself arrested at his home two months later, on the 23rd August, by ten or twelve plainclothes policemen from the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), who searched the premise and removed, as well as O’Neill, two bicycles left there by the IRA, a bicycle belonging to the ICA, and a British Army motorcycle that had been commandeered by the ICA. “The police were warned that they were seizing political stuff and breaking the truce” – in reference to the ceasefire in July 1921 between the Irish insurgency and the British authorities – but “the detective stated that this was merely a civil and not a political case”; in other words, under terms not covered by the Truce.

Worse, after O’Neill was taken to Bridewell Station, the sergeant in charge stated that:

…the police were working in “conjunction” with the IRA and that the Commandant [O’Neill] had not been connected with politics for several months or words to that effect.”

Which was something the rest of the ICA Army Council was refusing to let be. “We are determined not to stand idly by while the Commandant” – by then a resident of Mountjoy Prison – “suffers for what was an act of the whole Council,” Byrne warned Brugha.[6]

Acts of War or Profit?

During the course of the previous two and a half years, in the conflict to be known as the War of Independence, the Anglo-Irish War or the Tan War, the IRA had been fighting tooth and nail against the British state in Ireland. The ICA had played its part in this – a supportive role, perhaps, but a part all the same; now it appeared that the IRA had aided the DMP in arresting the commanding officer of its ally. A similarly convoluted picture emerged at a meeting of the ICA Army Council in August 1921, where O’Neill’s predicament was the main topic of discussion.

In attendance were six members of the Council, with Countess Markievicz as the acting commander in O’Neill’s absence, as well as Gearóid O’Sullivan, representing the IRA GHQ as its Adjutant-General. “They all spoke together for some time and subsequently they told me they came to talk to me about the accusations against their Commandant Jim O’Neill,” wrote O’Sullivan in his typed report to the rest of GHQ.

The Bolands robbery, the ICA leaders asserted, was:

- Done under their auspices.

- For the purpose of obtaining money to buy arms.

- An “an act of war”, making it perfectly legitimate.

As O’Neill should not thus have been arrested, the rest of the Army Council “wished to discuss his position as a prisoner in the hands of the enemy and to arrange for his release by peaceable or other means” – the latter, they presumably meant, by armed force. Furthermore, O’Sullivan relayed, “they asserted that they understood that there was a working arrangement between Jim O’Neill” and the IRA, as well repeating the earlier claim that the IRA had assisted in O’Neill’s arrest and were “now co-operating with the enemy police with a view to his conviction.”

It was a claim O’Sullivan did not confirm or deny to the Council, only asking for proof. Sergeant O’Shea responded by providing three such points: (1) the Station Sergeant at Bridewell Station had said as much to O’Neill’s wife when she was there, (2) Jerry Murray, a van-driver for Bolands who also belonged to the local IRA battalion, had his house surrounded and guarded by other IRA members, who instructed him to give evidence against O’Neill, (3) other witnesses had apparently also been told by IRA intelligence officers “to go ahead.”

O’Sullivan did not comment on any of this in his report – it is possible that he was unsure as to the full picture. Of more immediate interest to the Adjutant-General was the money stolen in the heist: £1,300 altogether had been taken from Bolands, yet only £700 was passed on to the ICA Army Council. “There is no information of the remaining £600,” he noted.

‘A Certain Amount of Consternation’

The ICA had gone into the meeting as the aggrieved party. Now O’Sullivan turned the tables, revealing to the Army Council, causing in the process “a certain amount of consternation,” that:

O’Neill had no official connection with us [the IRA GHQ], and when I produced a list of goods passed by O’Neill to our Q.M.G. [Quartermaster-General] and for which O’Neill received £112. The Council believed that these guns were being passed to the Army [that is, the IRA] on loan and had never heard of any sum of money having been received by O’Neill with the transaction.

It seems O’Neill had not been keeping his ICA colleagues entirely apprised in his dealings on their behalf (which supports the accusations Robbins was to make in his memoirs). Although not explicitly stated by O’Sullivan, his readers could have presumed that the money made by O’Neill on his sales to the IRA Quartermaster-General had – like the unaccounted-for £600 from the Bolands robbery – not been passed on to the rest of the ICA. As if that was not damaging enough to O’Neill’s standing, O’Sullivan next read out a list of a dozen or so other robberies linked to O’Neill and some associates of his.

Instead of liberating their Commandant, the Army Council members now had something a little different in mind: they still wanted O’Neill free but so they could deal with him themselves. O’Sullivan, however, was distinctly cool on the idea of entrusting the ICA with anything:

I think it is better that O’Neill should remain in prison and I think it is a good opportunity of clearing up this matter of the Citizen Army. At the moment I believe the whole Council should be placed under arrest in connection with the robbery of Bolands, but as this would entail the arrest of a Minister of Dail Eireann I should like to have special instructions.

The person in question was Countess Markievicz, serving, among the many hats she wore in her revolutionary career, as the Minister of Labour. As arresting someone in such a public and political role would create consideration complications, O’Sullivan was wise to hold off, pending further instructions. He did add that Markievicz was the only one on the ICA Council not implicated in the theft of money, to buy arms or otherwise. She had, after all, been in prison at the time.[7]

‘Under the Cover of Political Warfare’

O’Neill would thus not be leaving his cell in Mountjoy anytime soon. There seems to have been little doubt among contemporaries as to his culpability. O’Sullivan did admit, in another report, that “we have no evidence against O’Neill,” but even this was used as evidence for the prosecution: “I am sure this fact only proves O’Neills [sic] cleverness.”[8]

The man himself stoutly held to his innocence, at least when before the court at the City Commission, Green Street, Dublin, on the 1st November 1921. He knew no more about the theft at Bolands than any of the jurors before him, O’Neill told the assembled body; indeed, he was glad, he continued, of not being out on bail the previous week due to another bakery firm having been similarly robbed and he would not want to be a suspect in that one as well.

According to the court, £1,334 had been stolen from Bolands – which matches the sum O’Sullivan cited, and not the smaller amount the ICA Army Council initially believed had been taken on its behalf. Another contradiction is that of the rosy view of the robbery as a quick, quiet affair, as initially depicted by Byrne – employees at Bolands were reportedly put “in bodily fear and danger of their lives” at gunpoint. Overseeing the City Commission, Mr Justice Samuels summed up the allegation as “of a very grave and serious character,” and that “recently in Dublin robberies had taken place that had no authorisation from any power whatever, except an organised band of well-skilled thieves.”

Indecision by the jury caused the case to be postponed until later in the month, on the 18th November, and the accused – described by newspapers as “a young man of powerful build” and “a respectable-looking young man” – was removed from the court. At his next trial, O’Neill once more pleaded ‘not guilty’ before conducting his own defence. The line – if there was one – between the political and the criminal was again addressed, this time by the prosecutor, Mr William Carrigan.

“These crimes,” he said, “had hitherto been carried on under the cover of political warfare, but the fact that these crimes had no political connection was shown from the circumstances that, since the cessation of strife in June last [due to the Truce], the number of these raids had increased in frequency.”[9]

The unsettled state of Dublin was illustrated in a report by the IRA GHQ, composed as part of its own investigation. Fourteen separate incidents were listed, carried out, it was believed, by members of the ICA. These included, along with Bolands, two bank heists on Camden Street, the holding-up of bread van drivers on Howth Road, an attempted robbery of the Dolphins Barn Post Office and two stick-ups of men from the Jewish community.

The ICA Army Council at least took responsibility for Bolands at its second meeting with O’Sullivan a month after the initial one, on the 5th September 1921. That particular deed had been “an official thing”, sanctioned by the Council for the purposes of fundraising (the missing £600, however, remained unaccounted for). O’Sullivan was unimpressed. He believed that two of the Council members, Captain Kelly and Sergeant O’Shea, had done more than merely permit the crimes, being themselves “active members of the Robber Gang” along with O’Neill.

A Final Verdict?

“Something must be done with the ICA,” wrote the IRA Adjutant-General, disgust and frustration palpable in his report:

There is [sic] some honest fellows in it…I would suggest their being disbanded; of course we must secure their arms. They are a danger now and will always be such no matter what way the War [with Britain] goes.[10]

As it turned out, no such move was made against the Irish Citizen Army. Byrne, the then ICA Honorary Secretary, believed that it had been decided instead that “it was better to put the man away,” as in leaving O’Neill behind bars, out of sight and hopefully out of mind, rather than risk the potential clash. After all, O’Neill’s treatment was not unanimously accepted by the rest of the ICA, there being “at the time…disagreement over O’Neill’s case,” for which Byrne was among those blamed. Things were awkward enough, even years later, for Byrne to put off applying for a military pension as it would involve contacting former comrades on the Army Pensions Committee.[11]

In his own pension application, O’Neill was notably coy on the issue. When asked if his imprisonment had been due to his role in the revolution, all he said was: “Yes, certainly, but I was not arrested as a result of having participated.” By the time of his next trial, on the 10th February 1922, O’Neill had already been acquitted of the Bolands’ robbery, only to be left with more charges of theft, these ones relating to the bicycles and the motorcycle found on his property. Pleading not guilty again, O’Neill played the ‘political card’: he had only been holding the items in question as per his orders from the IRA. This was flatly contradicted by the body in question, via its liaison officer, making it clear that the defendant was on his own.

“There was something very misleading about the case,” O’Neill remarked, to laughter in the chamber. He was one to talk. An attempt to evade the court had been made on his behalf when a letter signed ‘James Byrne’ was received, in which the author, describing himself as an ‘Adjutant’, repeated the defence that O’Neill’s actions had been sanctioned by the IRA. Not only did the IRA liaison officer refute this claim as well, he denied there was any such adjutant in the IRA by that name. The Judge commented only that the new Irish Powers-That-Be had washed their hands of the affair – and then passed a sentence of three years.

And so “a remarkable series of trials came to a close,” wrote the Irish Times, which paid tribute to the story’s protagonist in his display of “remarkable intelligence in the conduct of his own defence.”

That was not quite the end of the drama, however. O’Neill was rearrested later in 1922, on the eve of the Civil War, this time by the pro-Treaty faction of the IRA – “purely on my reputation,” O’Neill explained, as he was no longer involved in the ICA. Since he had just returned to Dublin from a visit to the countryside, he must have been freed before then, probably due to the amnesty of POWs and other political prisoners.

If so, then O’Neill was lucky, being considered “a discredited Republican at that time,” according to Oscar Traynor, a Dublin IRA commandant, who gave evidence regarding O’Neill’s pension bid. “He had to go before a court; he was in a little trouble,” Traynor said, which is something of an understatement. By the time of the revolutionary pension applications, in 1936, O’Neill appears to have been in charge of the ones for ICA members. Traynor expressed surprise as this, since “I thought he had been ostracised” – a tribute, perhaps, to the silver tongue of O’Neill’s that Robbins so resentfully recalled and the Irish Times fulsomely praised?

Traynor did not hide his contempt for the ICA before the pension board, dismissing its members as having been hopelessly disorganised during the War of Independence. He did concede that O’Neill had been a senior officer in it, from whom the Dublin IRA purchased munitions such as gelignite, rifles and ammunition. Traynor did not go into the whole murky matter in quite as much detail as others would do, but he noted that, of the sales O’Neill made, the money “apparently…never reached the Citizen Army.”[12]

References

[1] Robbins, Frank. Under the Starry Plough: Recollections of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: The Academy Press, 1977), pp. 202-4

[2] Ibid, pp. 215-6

[3] Murphy, Angela, ‘Robbins, Frank’, Dictionary of Irish Biography (Accessed on 07/11/2023)

[4] Rooney, Catherine (BMH / WS 648), pp. 16, 28

[5] Fox, R.M. The History of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: James Duffy and Co. Ltd., 1943), p. 205 ; O’Riordan, Turlough ‘Fox, Richard Michael’, Dictionary of Irish Biography (Accessed on 17/11/2023)

[6] Military Archives – Cathal Brugha Barracks, Michael Collins Papers, ‘Correspondence and statements connected to a robbery at Bolands Mill, 25 June 1921 which was carried out by the Irish Citizen Army’, IE_MA_CP_05_02_50, pp. 2-4

[7] Ibid, pp. 5-6

[8] Ibid, p. 16

[9] Irish Times, 02/11/1921 ; Evening Herald, 18/11/1921

[10] Military Archives, ‘Correspondence and statements…’, p. 16

[11] Military Pensions Service Collection, ‘Byrne, John’ (MSP34REF17897), pp. 38-9

[12] Irish Times, 10/02/1922 ; Irish Independent, 10/02/1922 ; Military Pensions Service Collection, ‘O’Neill, James’ (MSP34REF8368), pp. 33-4, 38-40

Bibliography

Books

Fox, R.M. The History of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: James Duffy and Co. Ltd., 1943)

Robbins, Frank. Under the Starry Plough: Recollections of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: The Academy Press, 1977)

Dictionary of Irish Biography

Murphy, Angela, ‘Robbins, Frank’

O’Riordan, Turlough ‘Fox, Richard Michael’

Bureau of Military History Statement

Rooney, Catherine, WS 648

Military Archives – Cathal Brugha Barracks

Michael Collins Papers, ‘Correspondence and statements connected to a robbery at Bolands Mill, 25 June 1921 which was carried out by the Irish Citizen Army’, IE_MA_CP_05_02_50

Newspapers

Evening Herald

Irish Independent

Irish Times

Military Service Pensions Collection

Byrne, John, MSP34REF17897

O’Neill, James, MSP34REF8368

“If you or anybody else expect that I’m going to waste my time talking ‘bosh’ to the crowds,” James Connolly was heard to say, “for the sake of hearing shouts, you’ll be sadly disappointed.” He preferred instead to “give my message to four serious men at any crossroads in Ireland and know that they carry it back to the places they came from.”

“If you or anybody else expect that I’m going to waste my time talking ‘bosh’ to the crowds,” James Connolly was heard to say, “for the sake of hearing shouts, you’ll be sadly disappointed.” He preferred instead to “give my message to four serious men at any crossroads in Ireland and know that they carry it back to the places they came from.”