Rights and Authority vs Hidden Forces

Michael Collins was a busy man in April 1921, but not too busy to respond to a letter from a Mr Meagher in Australia. Meagher was curious about the recent state of affairs in Ireland, fought over as it was by the British military authorities and the Volunteers of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and Collins, with an eye to PR and perhaps out of genuine helpfulness as well, took the time to answer his correspondence point by point.

To Meagher’s query – “Is there any truth in the report that Sinn Fein is controlled by the IRB?” – Collins was emphatic that “to make such a suggestion is to show an entire misconception not only of the relative positions of these separate organisations but of the whole Irish situation.” Since its inception sixty years ago, the policy of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) had been that of the current independence movement and, as such, “it may be called the parent of all present day Irish Ireland organisations.”

Nonetheless, despite this prestige, despite the venerability of the IRB:

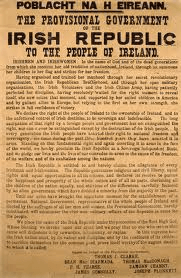

One body only has the right and authority to speak and it is the body brought into being by the freely exercised will of the Irish people. It is DAIL ÉIREANN. That is the Government of Ireland, and to it all national organisations within Ireland give allegiance.[1]

Spoken like a true democrat. Others, however, might have looked askance at this answer and wondered if its author was being entirely straightforward in his avowedly unambiguous response. Certainly, the O/C of the Sligo IRA Brigade felt he needed clarification when some of his subordinates committed a raid on a mail car, during “which some hundreds of pounds [in] letters were taken without the sanction or knowledge” of the rest of the Brigade.

Since there appeared to be “hidden forces at work that are not working for the greater efficiency of the Volunteers,” the O/C wrote to Collins, then the IRA Adjutant-General, in April 1920, asking about “the attitude of the Irish Volunteer organisation to the IRB,” to which the raiders had apparently belonged.[2]

Collins’ response a month later, as with his one to Meagher, was to dismiss any suggestion of a conflict of interests:

Arising out of your letter…re attitude of Irish Volunteers and another organisation, you will notice that there is no difference between the aims and methods of the Irish Volunteer Organisation and the other one you mention.

Noticeably, Collins did not refer to the ‘other one’ by name, as if too delicate an issue to touch directly. That was not to say that its members could act with impunity, as Collins instructed the Sligo commander to arrest the perpetrators of the mail car robbery and relieve them of their ill-gotten, and unauthorised, gains.[3]

Even so, questions continued, for Sligo was not the only IRA area uncomfortable with compromised authority. In May 1920, Collins received a letter from the Adjutant of the Leitrim Volunteers, asking him who among their ranks were in the IRB as well due to the suspicion that these Brotherhood insiders “seem to have power over us.”[4]

Elements of Consciousness

If Collins replied, then his answer has been lost to posterity, since most of the subsequent sheets in that particular batch – stored in the National Library of Ireland with the rest of his papers – are in tatters, rendering their words illegible. In any case, Richard Mulcahy was not impressed with how the Library was handling the memoranda of his old comrade. “They strike me as being the sweepings of some room,” he wrote with a sniff, “they in no way suggest the manner in which Collins kept his papers or that they were anything but crumbs indicating certain aspects of his varied work.”[5]

With his own eye on history, Mulcahy discussed the era with another former colleague, Peadar McMahon, in 1963. While Mulcahy had served as the IRA Chief of Staff during the War of Independence, McMahon worked as an IRA organiser, dispatched by GHQ to places deemed in need of assistance, one of which happened to be Leitrim. There, McMahon found a brigade not so much dominated by the IRB as oblivious to it:

Mulcahy: Did you ever on any of your moments on organisation work come across anybody who was consciously an IRB man as distinct from a Volunteer?

McMahon: No. In Leitrim, it was rather amusing; they pointed out ‘in such an area there is a man there who is a member of the IRB’. Otherwise you would never hear the IRB mentioned at all, simply GHQ, and because I was from GHQ they couldn’t do half enough for me.

Mulcahy: Was the fellow from the IRB an old man?

McMahon: I never met him. It was simply pointed out that he was there and I was interested enough to go and see him.

Mulcahy: Would he be from the Seán McDermott area – Kiltyclogher?

McMahon: He was. When I asked what age he was, I was told he was eighty-seven.[6]

Similarly underwhelming was McMahon’s own experiences, such as they were:

Mulcahy: When did you link up with the IRB or what contact had you with it?

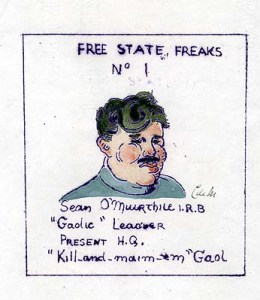

McMahon: In 1917. I was introduced to it by Seán Ó Muirthile and didn’t attend a meeting from the day he introduced me to it until that meeting – 1917 to 1922.

Mulcahy: So in these three years – 1917, ’18 and ’19 – you never attended an IRB circle and you never got instructions from anybody. Why was that? Was it that it satisfied the IRB requirements that you were a member of the Volunteers?

McMahon: I don’t know.[7]

Mulcahy concurred with that description. To him, the strength of the rank-and-file Volunteers had been their “air of comradeship, naturalness and understanding of the difficulties.” Loyalty was directed towards – in varying degrees – the IRA GHQ, Dáil Éireann and the underground Irish Government, but otherwise without any “element of consciousness of an IRB outlook or IRB organisation or IRB orders anywhere else.” As for policy: ‘Join the Volunteers and take your orders from your superior officer.’ Had McMahon, Mulcahy asked, ever been told anything different by anyone in the IRB?

“No, nothing else,” McMahon replied.[8]

A Disputed Dispute

Obviously, these are the conclusions of two men, speaking decades afterwards. At the time, the picture did not seem so simple; indeed, the Brotherhood was a sensitive spot for Mulcahy, considering how he had lost his military command, as did others in the Army Council, in no small part because of the secret society and its alleged role in the Army Mutiny of 1924. As with the subject of the IRB in general, much is open for debate, and little known for certain. Initial responsibility lay on the body of mutinous malcontents, the so-called IRA Organisation, wrote the Army Inquiry Committee in its report to the Dáil in June 1924.

However:

While we are completely satisfied that there would have been no mutiny but for the existence of this organisation [the IRA Organisation], we are equally satisfied that its activities were intensified by the revival or reorganisation of the IRB, with the encouragement of certain members of the Army Council.[9]

It had all been “a disastrous error in judgment,” concluded the Committee. According to Mulcahy, however, he and other ‘certain members’ in question had only the best of intentions in reforming the IRB:

[Mulcahy] suggested to the Dáil that there was in that organisation a force that required to be controlled and directed, and that he, as the Minister responsible, should take steps to have that force stabilised in the Army.[10]

Whatever the original motive, stability was the last thing achieved, least of all for Mulcahy’s career, as he was forced to step down as Minister of Defence. So did Seán Ó Muirthile as Quartermaster-General, Adjutant-General Gearóid O’Sullivan and the Chief of Staff, Seán MacMahon. Kevin O’Higgins was the chief winner of the debacle, out of which the Minister of Justice emerged as the defender of the civilian government, strongman of the state and vanquisher of troublesome cabals.

Assuming there had been an IRB left by that stage. McMahon found the whole affair puzzling and more than a little absurd because, as he told Mulcahy in August 1963, the Brotherhood had already been wrapped up by the time O’Higgins flexed his political muscles:

McMahon: [The] statement that Kevin O’Higgins supressed the IRB was ridiculous. Months before that, I was called to a meeting at the private secretary’s lodge in the Phoenix Park. Martin Conlon was there, Gearóid O’Sullivan, Seán Ó Muirthile, Dan Hogan, Eoin O’Duffy and I think that was the lot. The meeting was called to bring the IRB to an end. It was feared that some irresponsible people were trying to get control of it, and the funds, which at that time were in the hands of Eoin O’Duffy, were handed over to Martin Conlon. The statement that Kevin O’Higgins supressed the IRB came as a big surprise to me.

Mulcahy: Are you sure that that meeting was before the army episode?

McMahon: Yes. As a matter of fact, Gearóid O’Sullivan was Adj. General, Seán Ó Muirthile was Quarter Master General.

Mulcahy: Was that the end of the contact with that question that you had?

McMahon: Yes, that was the end.

Mulcahy: Do you remember any kind of meeting that was held in Portobello that I am supposed to have been at, at which the various O/Cs of the various divisions were pressed for the purpose of reorganising the IRB?

McMahon: No, I never heard of it even and I am sure I would have been there if there had been such a meeting. I didn’t hear the IRB discussed from that particular meeting until –

Mulcahy: Would you be able to get an approximate date for that?

McMahon: It would be difficult, but it must have been before it because I know that Gearóid O’Sullivan was Adj. General and Seán Ó Muirthile was Q.M.G.

Mulcahy: In what capacity in the IRB were you there?

McMahon: In no capacity.[11]

‘The Whole Caboose’

Which is the opinion of one man. Others would differ, pointing to the Brotherhood as not only active but ambitious, with an eye to the future as much as the present. Though the ‘IRB Constitution – 1923’ was tentatively labelled ‘Provisional’, its contents speak of an organisation determined to be anything but.

The Supreme Council was to be expanded to twenty-eight members: one from each of the sixteen IRB Divisions encompassing Ireland and Britain, four co-opted and the remaining eight – most significantly – out of the eleven Divisions in the National Army (in comparison, the earlier 1920 Constitution only anticipated a need for fifteen Supreme Councilmen). To accommodate military initiates, they were to form ‘Clubs’, each headed by a Centre who would report up the societal chain of command, and not exceeding ten-strong unless authorised by the Supreme Council – exactly like the civilian ‘Circles’ of before that were clearly intended to continue on, running parallel now with the new Clubs. These were no idle musings, either, for a note in the margins identified Mulcahy and Ó Muirthile, men at the very top of the National Army, as the ones presenting this proposed document to their peers.[12]

The future of the IRB had been under consideration for some time, as Ó Muirthile wrote in his memoirs. The Supreme Council, on which he sat, had not been active for a while, nor were local branches across Ireland as far as he knew, leaving the organisation in limbo and its adherents uncertain. After hearing of these concerns from others in the National Army, Ó Muirthile raised the issue with the remaining Supreme Council members and it was agreed, at a meeting in January 1923, that:

- The proud tradition of the IRB should be preserved and passed onto those loyal to the Free State government.

- This effort would fall upon the previous members of the Supreme Council.

- The Free State government must not be prejudiced or subverted in any way even if any members of its Executive Council were also in the IRB.[13]

Unlike Mulcahy and Collins, who had their roles in the IRA and government as well as the IRB, Ó Muirthile’s place in the Irish struggle was largely defined by the Brotherhood – and perhaps the IRB was defined in turn by him, considering the length and level of his involvement. It was he who chaired a special meeting in Dublin, in early 1917, for the purpose of reorganising the fellowship since the shock of the Easter Rising failure and the decimation of its leadership in the resultant executions. His ‘take charge’ attitude and garrulousness did not endear him to everyone in the room, with one delegate from Galway feeling that Ó Muirthile thought “that he was the head of the whole caboose.”[14]

Another acquaintance immune to his charms was Ernie O’Malley, who remembered Ó Muirthile as “a big, burly man with a thick moustache and a prosperous air, pudding rolls at the back of his neck.” While conceding that Ó Muirthile was a good speaker and “considered a man of weight…I did not like him from the first.”[15]

Civil War bitterness might have coloured these reminiscences, for the two men were to choose opposing sides in that internecinal conflict, during which O’Malley identified the Free State enemy so much with the Brotherhood that he wrote in April 1923, while under threat of execution in Mountjoy Prison, of his life resting “on the whims of an IRB clique.”[16]

Lingering memories of that unpleasant experience would be channelled into academic interest. When interviewing to his peers for posterity, O’Malley was wont to ask, as one other historian puts it:

…frequent questions about the functions of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), especially in regards to its impact on the Anglo-Irish Treaty split. O’Malley was not a member of the IRB, so he had little personal understanding of its internal working and seemed to want to educate himself as to the importance of the IRB in the division of the IRA over the Treaty.[17]

“Did IRB also think it would be IRB who would do as they were told in the case of the Treaty?” O’Malley asked himself in the margins of his notebook when discussing with an interviewee the dominance of the fraternity over the 1916 Rising.[18]

In another interview, he was sceptical about Joe Sweeney’s claim that the IRB had never tried to persuade him over the Treaty. O’Malley reminded him about a book in which the author, Piaras Béaslaí, revealed how the Supreme Council had informed IRB members who were also TDs of its decision to back the Treaty.

“Yes,” said Sweeney, “I remember that.”

“Yes,” said Sweeney, “I remember that.”

“Didn’t you think that was a lead?’ O’Malley said, with just a hint of a sting in his words.[19]

Leading and/or Deciding

O’Malley was not alone in his suspicions – or bitterness. Unsure as to which side to take in the looming schism, Seamus McKenna consulted Pat McCormack, a man greatly respected amongst Belfast republicans and who had sat on the IRB Supreme Council. McCormack’s advice was to stick with the IRA GHQ and choose, by default, the Treaty. Eight or months later, McCormack changed his mind but the damage, as McKenna was concerned, was done: “He had…already compromised, and led others along the same path.” Not that McCormack was alone in his perceived apostasy, McKenna being “sure that many other IRB men accepted the ill-fated Treaty on the advice of their officers in that organisation.”[20]

It is notable, however, that McCormack was giving solicited advice rather than orders. The grandiosity of its name aside, the Supreme Council had a tenacious hold on its followers, one that could be dropped, seemingly at will, such as when Tom Maguire chanced upon Michael Thornton in a hotel hallway during the Treaty crisis in early 1922. As part of the IRB Connaught Council, a halfway body between the Supreme Council and the Circles in that province, Thornton stood above Maguire in the IRB hierarchy.

Yet, when Thornton told of the Supreme Council’s siding with the Treaty, Maguire replied that meant nothing to him; he was a free agent and would do whatever he thought was right. Thornton left at that point, and Maguire, far from suffering consequences for his independence, continued in his rank as a Mayo IRA commander, leading his troops against the Free State in the subsequent Civil War.[21]

Even those who went the other way could do so not because of the IRB but despite it. Joe Sweeney would be one of the Free State’s most active generals in the Civil War; this despite him not wanting anything to do with the Treaty when he first read of its signing in the newspapers. A cautious man, Sweeney nonetheless travelled to Dublin from Donegal, where he led its IRA Brigade, to consult with the President of the Supreme Council.

Seeing a depressed and worn Collins in the Wicklow Hotel, Sweeney decided against bothering a man already under visible strain. Instead, Sweeney found O’Duffy in the hotel and took him aside. Regardless of O’Duffy’s own high placement in the IRB, he could offer nothing more definite than how it was up to Sweeney to decide for himself. It was only after Sweeney returned to Donegal and discussed with local Sinn Féin acquittances that he threw his lot in with the Treaty.[22]

O’Malley would privately doubt all this, thinking that “Sweeney prevaricated about his attitude to the Treaty.” Who had decided him? he jotted to himself in his interview notebook.[23]

‘This Splendid Historic Organisation’

O’Malley’s snide cynicism aside, there is no reason to think Sweeney was any more an unthinking drone than Liam Lynch, who did not let his own membership – not just of the IRB but of the Supreme Council itself – stop him from directing the anti-Treaty forces in the Civil War. Indeed, in November 1922, five months into the conflict, Lynch was thinking up ways to reclaim the Brotherhood for his cause and thus redeem “the honour of this splendid historic organisation,” as he put it in a letter to his right-hand man, Liam Deasy.

Lynch was by then the last Supreme Council member who opposed the Treaty still alive – Harry Boland had been killed in August 1922 – and at liberty, unlike Joe McKelvey and Charlie Daly. With responsibility now solely on his shoulders, Lynch outlined to Deasy how he would go about things: an adjourned meeting from before would be reopened, in which his Supreme Council colleagues who had voted for the Treaty were to be held to account, suitably castigated by the middle-ranking IRB officials in attendance and then cast out, allowing the ruling body to be filled with more Republican-minded replacements. In the event of this meeting being refused, then Lynch would dispense with formalities and drop the pro-Treaty dissenters from his reformed Supreme Council all the same.[24]

Was this plan plausible? Not just Lynch thought so. Boland had previously outlined, in a letter on March 1922, that he and his allies in the IRB “were not anxious to force a division until such time as we were satisfied of securing a majority vote.” By April, Boland believed that majority vote was his for the taking:

The organisation holds a Convention next week, at which I am certain the proposed Free State will be condemned and all those favouring it will be asked to resign. The new S.C. will, I hope, throw all its strength behind the Army.[25]

Both Lynch and Boland were angling for the Supreme Council as the prize, while believing it vulnerable to a putsch from below. Giving credence to this thinking was how – going by its 1920 Constitution, the then most up-to-date version – the IRB was, if not quite democratic, then at least reasonably representative: those in its Circles, the basic unit of the organisation, would elect a Centre, who would in turn vote in Centres for County Circles and the District Boards (each Irish county being divided into two or three Districts, with cities counting as a District in themselves).

County Circles and the District Boards were grouped into the eleven Divisions encompassing the IRB’s sphere of influence: eight Divisions for Ireland, two for the south and north halves of England, and one for Scotland. Centres for the County and District Circles in each Division met to select by ballot a five-strong committee, which in turn would appoint someone to represent the Division on the Supreme Council. These eleven men, one for each Division, would co-opt four additional members, leading to a total membership of fifteen for the ruling body.

Putting Up and Shutting Up

Which meant that the Supreme Council could not be completely indifferent to lower-tier feelings, and while it claimed in the IRB Constitution that its “authority…shall be unquestioned,” reality sometimes fell short of this totalitarian assumption. The Treaty divisions of 1922 may have pushed fraternal feelings to breaking point but, even as early as 1917, the leadership could not count on unconditional loyalty.[26]

A case in point was when the Galway University Circle received an envoy from the Supreme Council, Patrick Callaghan, as part of the IRB’s resurgence that Ó Muirthile had prompted in Dublin. Callaghan opened the session with a criticism of Éamon de Valera, the newly-minted political dynamo of the independence movement. Callaghan did not last two minutes before Dr Pat Mullins, as the Circle Centre, shut him up with: “If that’s what you’ve come over for, you’d better get back to where you came from.”[27]

A case in point was when the Galway University Circle received an envoy from the Supreme Council, Patrick Callaghan, as part of the IRB’s resurgence that Ó Muirthile had prompted in Dublin. Callaghan opened the session with a criticism of Éamon de Valera, the newly-minted political dynamo of the independence movement. Callaghan did not last two minutes before Dr Pat Mullins, as the Circle Centre, shut him up with: “If that’s what you’ve come over for, you’d better get back to where you came from.”[27]

Another Mullins, Billy Mullins from Kerry, also had a snippy exchange with an IRB superior, this time during the Truce of late 1921. After meeting with Liam Deasy and Ó Muirthile, Mullins was asked by Deasy about continuing the work of their Brotherhood.

Mullins: I’ll ask you a question first. Who is responsible for carrying on the activities of the IRB now?

Deasy: I’ll answer you now. Seán Ó Muirthile.

Mullins: If that’s the case, you can count me out.[28]

(Ó Muirthile evidently had that effect on people.)

Mullins stayed with the Brotherhood long enough to attend a meeting in Tralee in January 1922. Twenty-five had come, an unusually high turnout according to Mullins, who was clearly used to smaller, more secretive gatherings. After a discussion on the Big Question of the Day, “the meeting finished with a motion that further inquiries be made, but the result was that nothing happened, as it never seemed to come to anything.” Still, Mullins felt that “the majority there present…were in favour of the Republic” and against the Treaty – so much, then, for the Supreme Council controlling its underlings like obedient puppets.[29]

Also present at this Tralee conclave was Dinny Daly, who came away thinking that “more or less left it was to everyone to do what they liked.” Personal connections seemed to count for more than direction from above: “When the officers went one way, the men followed them.”[30]

Paying the Piper and Calling the Tune

This is not to say that the Brotherhood simply ceased to function: perhaps to the alarm of the Supreme Council’s pro-Treaty majority, the IRB provided a convenient framework for county or provisional representatives to vent their feelings. An example of this was on the 18th of February 1922, when a passed resolution in Cork expressed approval of how the Cork County Centre and Division Boards had withdrawn their support from the IRB upper echelons over the Treaty. Meanwhile, a report from Co. Kerry proudly told of how the Supreme Council’s decision had practically no effect on its Circles there, with pro-Treaty numbers remaining negligible.[31]

In Dublin, Circles expressed a range of reactions, as summarised in a notebook in April 1922, from wary reserve – “that a meeting of all Dublin centres be called to discuss the circumstances of the present crisis and that a member of SC be deputed to attend and explain position” – to anger and threats to withhold subscriptions “until such time as S.C. cease to consider us as Kindergarten Kids.”[32]

Little wonder, then, that Lynch and Boland had assumed they would have the numbers to retake control of the Supreme Council. James McArdle caught the complex, even ‘love-hate’, nature of the relationship between the top and lower ends of the Brotherhood in a letter to Martin Conlon, a member of the Supreme Council. McArdle apologised in advance for his absence and that of his like-minded colleagues at an upcoming IRB session, though he hoped that Conlon:

…will be both able and willing to defend us here from any attacks that may possibly be made on us during our absence there, or any insinuation against our sincerity for the cause, for which we are now stronger than ever, now that it has again fallen to the minority to uphold.

McArdle had evidently been expecting an unfriendly reception; regardless, he was sure that:

If our own members, the C.B. [County Board] or the S.C. require any explanation from us, for our attitudes or actions in the present conflict we will be able to give them, and vindicate ourselves before any impartial [underlined in text] tribunal of the organisation still loyal to its principles.

It was a loyalty McArdle doubted was shared by the majority of the IRB. Undeterred by the numbers against him and emboldened by the righteousness of his defiance, McArdle demanded from Conlon:

…the right to know what steps – if any – that the S.C. takes from now onward as we, the rank and file of the organisation have always to pay the piper, we claim the right to call the tune, or at least be consulted as to what tune is to be called.

Not that McArdle was likely to be consulted on much by the Supreme Council, not anymore. His letter was dated to the 29th August 1922, two months and a day into the Civil War, with the address given as Kilmainham Gaol, where McArdle was an unwilling resident and POW.[33]

A High Sense of Duty

“Only a high sense of duty could have driven a group of disciplined officers in such open conflict with their superiors,” wrote Florence O’Donoghue when describing the turbulence within the IRB:

They acted against a discipline all the more precious to them because it was voluntary and respected, against that almost mystical loyalty which bound them to the organisation in good times and bad.[34]

O’Donoghue could relate. After wrestling with his dual loyalties to the Brotherhood and the Cork IRA Brigade, he chose the former and went to his commanding IRA officer to resign as Brigade Adjutant. This, Tómas Mac Curtain refused to accept, insisting that O’Donoghue remain and saying nothing subsequently about the other man’s continued membership of a society he was increasingly at odds with.

Mac Curtain had walked out of prison in 1917, believing, as did many other “responsible leaders” in the independence movement that “there was no further need for a secret movement, that the IRB should be allowed to lapse, and the whole future struggle should be based on the open political and military organisations” like Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers (later the IRA) respectively, as O’Donoghue put it. O’Donoghue, on the other hand, respected the IRB’s singular purpose and determination to fight for Irish freedom, in contrast to the vacillating strands of thought he found in the Volunteers, many of whom believed in physical force only as a last resort – to his dismay – and sometimes not even that.

Complicating things further was how the Vice-Commandant to the Cork Brigade, Seán O’Hegarty, was also the IRB County Centre, an additional authority that he was not afraid to wield. While Mac Curtain made no move to restrict the parallel command within his ranks, tensions came to a head with the unauthorised shooting and wounding of a policeman, in April 1919, by a Volunteer who claimed that the right to carry arms had been granted to him by O’Hegarty. This challenge to the Brigade chain of command could not go unanswered, though O’Donoghue was to claim the controversy had been blown “out of all proportions to its importance.”

In any case, O’Hegarty resigned as Vice-Commandant, “not a complete solution, but it was a gesture to the authority of Tómas, and it left Seán’s IRB position intact.” And it was a position jealously guarded:

Seán would not and could not be expected to abate anything of his IRB authority, but was quite willing to work on co-operation with the Volunteers provided they were on his road.

O’Donoghue was able to stay on amicable terms with both Mac Curtain and O’Hegarty even as he kept a foot in each of their camps. Perhaps out of memory for his friends, O’Donoghue – in his later career as a historian – was to characterise the trouble between them as a gentlemanly dispute over honourable principle. It is possible, however, that Mac Curtain’s murder at the hands of policemen saved relations in Cork from worsening irreconcilably – and allowed the IRB to completely dominate the IRA there.[35]

By the Easter Sunday of 1921, the Brotherhood could claim a good number of leading Cork officers, many of whom met other South Munster IRB leading lights in a house at Palmerstown Park, Dublin. Presiding over it, in more ways than one, was Collins – the President of the Supreme Council – who set the agenda: the delegates were to return to their areas and expand their Circles with fresh blood of proven worth.[36]

His audience took note. “After that we put any man of importance in West Cork into the IRB,” recalled Liam Deasy.[37]

He was by then Adjutant to the West Cork IRA Brigade, having joined in 1917 while part of the Bandon Company. Tom Hales soon swore him into the IRB after convincing him of the importance of the fraternity in the upcoming struggle. From there, Deasy rose steadily in the two parallel organisations, seeing no clash of interests between attending an IRB conclave one day and an IRA GHQ strategy meeting the next.[38]

Only Silent Men

In keeping with a body concerned with gathering influence, the IRB was interested primarily in those with clout of their own to share. Elitism was the attitude as well as an objective unashamedly pursued. “Only Bn [Battalion] and Bde [Brigade] officers sworn,” recalled Tom O’Connor from Tralee, Co. Kerry. Mere company officers or below were apparently not to be bothered with.[39]

When Patrick McDonnell wanted to induct the entirety of his East Clare Flying Column, he was dissuaded by Ernest Blythe, who advised him to be selective: “Only the very select few you want in the IRB.” It was a case of quality over quantity, and the virtue that Blythe prized most of all was taciturnity – he wanted “only silent men.” But reticence could have its drawbacks; McDonnell never informed his colleague in Clare, Michael Brennan, that he was in the IRB, and neither did Brennan let McDonnell know of his own membership. Perhaps this state of one hand not knowing what the other was up to was why, in McDonnell’s estimation, “the IRB never developed much in Clare.”[40]

Others would remember the Brotherhood in almost comical terms. When John Joe Rice met its adherents in Kenmare, Co. Kerry, in 1917, he found them gagged with “the old idea that nobody was to be trusted with anything. They were good fellows but that idea had been drummed into them for years.” It took some time, but “as soon as they got over their initial fright of things being spoken about,” a working relationship was possible. Elsewhere in Kerry, Dinny Daly considered many of his Circle in Cahirciveen to be “a queer crowd…some of them I never thought should be in the IRB.” Of particular annoyance was how they approached Daly for recruitment after his release from prison, not knowing he was already a member: “I hauled them over the coals for being slipshod about it.”

Such ineptitude, however, did not prevent the Brotherhood from being “very strong in Kerry,” in Daly’s view. “I expect that all the officers in Kerry were IRB.”[41]

The underground nature of the IRB, even by the standards of the Irish revolution, and the insularity of its insiders, even among each other, makes its power hard to gauge – even to its members. John McCoy’s promotion to Belfast IRA Brigade Adjutant prompted Paddy Rankin, the IRB Centre for Newry, to hurriedly attempt to recruit him, seemingly “afraid that if I refused to join the IRB, headquarters might not sanction my appointment as Brigade Adjutant.” Due to McCoy’s “certain moral scruples” and belief that the IRA had rendered secret societies obsolete, he declined.[42]

Contrary to Rankin’s fears, McCoy remained as Adjutant. That he suffered no adverse effects to his IRA position made a mockery – in Seamus McKenna’s eyes, at least – of the IRB policy to seek only the best:

I understood at the time that the main function of the IRB was to control both the leadership and the activities of the Volunteer [IRA] movement from within by ensuring that senior officers were IRB men who would see that the fight for the Republic was relentlessly pursued.

However, “I cannot recall that this was effective in Belfast.”

Both the Belfast Brigade O/Cs, Seán O’Neill and his successor, Roger McCorley, kept aloof from the Brotherhood, apparently sharing McCoy’s ethical qualms; McCorley, in particular, earned McKenna’s respect as “one of the most daring and active Volunteer officers in Ireland.” In glaring contrast was Joe McKelvey, a fellow Belfast native, whose rise to O/C of the Third Northern Division, in 1921, McKenna attributed to IRB machinations despite his personal unsuitability for command. Two of the men in McKenna’s Circle made similarly poor examples by displaying “a lamentable lack of courage when the occasion for such arose.”

Of the group overall, though McKenna was a dutiful participant in its monthly get-togethers, he could not later “recall any useful purpose served by our particular Circle.” As convenient as the Brotherhood might have been before, “from 1918 onwards the organisation, in my opinion now [in 1954], did not justify its existence.”[43]

A Secondary Business?

Indeed, some struggled to remember the point at all. Boredom, even contempt, colours many a reminiscence of time inside the fraternity. “We had all been sworn in to the IRB, but we looked upon it as a kind of secondary business of no real importance,” said John Joe Rice of his fellow Kerry IRA officers. “It was, or would only be, of use if we had to go underground again. I don’t think we had circles or meetings even.”[44]

While many Volunteers highly placed in the Athlone Brigade – to choose an example – had been sworn into the IRB as well, they noticeably drew a blank about what the latter had actually done in the course of the War of Independence. Statements include:

Seumas O’Meara, O/C of the Athlone Brigade:

The organisation did not really serve any great purpose except to keep a strong backbone on the Volunteer movement. There was not, at any time, any attempt to direct Volunteer activities by the IRB in the area…When things were really hot and principally during the period of the Black and Tans, the IRB organisation became inactive and may be said to have practically ceased to exist.[45]

Henry O’Brien, Captain of the Coosan Company, First Battalion:

On the whole, the organisation did not seem any useful purpose, but it may have acted as a stiffener for the Volunteer force. When the military situation developed to the point when they became really hot and communications became impossible, the organisation kind of faded out and became inactive.[46]

David Daly, Commandant of the First Battalion:

It is hard to say what was really the objective of the organisation at this time in view of the policy of the Volunteers escept [sic] that it formed a hard core of resistance inside that organisation who would carry on the fight should the Volunteers weaken in their purpose.[47]

Frank O’Connor, Commandant of Second Battalion:

Business was of a routine nature and discussions on the existing situation in the area and the country in general took place and suggestions of what might be done to intensify the work were made. Such suggestions usually came to nothing. Looking back since, I cannot see that the organisation served any useful purpose, but the powers at headquarters seemed to think that it did.[48]

Reading all of this makes it easy to dismiss the IRB as largely a name and little else, a thing more theory than fact, or a Walter Mitty outfit compared to the IRA or Sinn Féin. A contemporary document, however, points to a more nuanced picture, one in which the Brotherhood was as capable of waxing as well as waning, and confident enough to prepare for its revival after lying dormant for months on end.

Judging an Elephant

Seán Murphy arrived in Co. Westmeath on behalf of the IRB central leadership, on the 22nd July 1921, in a tour of the Circles to be found there. He made contact with Thomas Costello and James Maguire, the Athlone and Mullingar O/Cs at the time, who were able to guide him to their societal grassroots. Meeting each cell was delayed by bad weather and sketchy communications – the latter in particular a common problem in the Irish insurgency – but, by the end, Murphy was able to draw up for his superiors a detailed breakdown of the Circles’ personnel:

Summerhill –

On roll: 11

Present: 8

In jail: 2

Absent: 1

Last meeting: October 1920

Coosan –

On roll: 14

Present: 10

In jail: 3

Absent: 1

Last meeting: October 1920

Blyse –

On roll: 17

Present: 14

In jail: 1

Absent: 2

Last meeting: 1920

Drumsane –

On roll: 22

Present: 16

In jail: 3

Absent: 3

Last meeting: 11th July 1921

Gleridan –

On roll: 7

Present: 4

In jail: 3

Absent: 0

Last meeting: October 1920

Castlepollard –

On roll: 13

Present: 3

In jail: 8

Absent: 2 (sick)

Last meeting: September 1920

(As all officers were in jail, Murphy recommended temporary appointments until elections for the roles could be held)

Bishopstown –

On roll: 10

Present: 7

In jail: 0

Excd.: 3

Absent: 0

Last meeting: October 1920

Mullingar –

On roll: 12

Present: 2

In jail: 10

One hundred and six delegates met at the IRB County Board on the 29th July 1921, the first since October 1920. That gap of nine months was typical of Westmeath, where the various Circles had had their last proof of existence in the previous autumn before fading out of the picture – but not necessarily out of existence, for Murphy felt “confident of good results owing to the present constitution of the organisation in the county.” Arrangements were already afoot to form new cliques in Loughnavaly, Kinnegad, Killucan and Moyvose.

Longford told a similar story when Murphy travelled there next. Delays were again suffered, this time blamed on poor roads, but Murphy came away believing that the effort had again been worth it: “The condition of the organisation in the county is very favourable and ought to improve considerably in the near future.”[49]

In his heroic attempt to make sense of the times, historian John M. Regan writes of how “the lack of available documentary evidence” makes for “no easy answers to the interpretative and methodological problems the IRB presents.” And that is only part of the headache, for the sources we do have are so wildly contradictory.[50]

Was the Irish Republican Brotherhood a splendid historic organisation? A sinister and manipulative cabal? A barely-there relic? An elitist pursuit or a pastime for oddballs? A democratic movement or the subversion of one? All are viewpoints put forward by contemporaries, each in a position to have known, and each like the Indian analogy of the three blind men who encountered an elephant. One touches its huge bulk and describes it as a wall, another thinks it a snake from the feel of its snout, while the third judges it to be a spear by its tusk – valid interpretations that nonetheless only capture part of the peculiar whole.

See also:

To Not Fade Away: The Irish Republican Brotherhood, Post-1916

References

[1] Military Archives – Cathal Brugha Barracks, Michael Collins Papers, ‘Copy Letter from Michael Collins to Mr Meagher to Australia’, IE-MA-CP-06-02-06, p. 4

[2] Ibid, ‘Sligo Brigade’, IE-MA-CP-03-36, pp. 2-3

[3] Ibid, p. 9

[4] Ibid, ‘Leitrim Brigade’, IE-MA-CP-03-35, p. 18

[5] University College Dublin (UCD) Archives, Richard Mulcahy Papers, P7/b/181, p. 1

[6] Ibid, p. 61

[7] Ibid, p. 16

[8] Ibid, p. 60

[9] Irish Times, 21/07/1924

[10] Ibid, 27/07/1924

[11] Mulcahy Papers, P7/b/181, p. 15

[12] National Library of Ireland, Florence O’Donoghue Papers, MS 31,236; the 1920 Constitution at MS 31,233

[13] Mulcahy Papers, P7a/209, pp. 177, 229

[14] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Comhraí, Cormac) The Men Will Talk to Me: Galway Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013), pp. 210, 212

[15] O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013), p. 120

[16] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007), p. 367

[17] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Bielenberg, Andy; Borgonovo, John and Óg Ó Ruairc, Pádraig) The Men Will Talk to Me: West Cork Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2015), p. 28

[18] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Horgan, Tim) The Men Will Talk to Me: Kerry Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), p. 60

[19] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Aiken, Síobhra; Mac Bhloscaidh, Fearghal; Ó Duibhir, Liam and Ó Tuama Diarmuid) The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018), p. 32

[20] McKenna, Seamus, (BMH / WS 1016), p. 45

[21] O’Malley, Interviews with the Northern Divisions, p. 218

[22] Griffith, Kenneth and O’Grady, Timothy. Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1998), pp. 264-5

[23] O’Malley, Interviews with the Northern Divisions, p. 32

[24] O’Donoghue Papers, MS 31,240

[25] Fitzpatrick, David. Harry Boland’s Irish Revolution (Cork: Cork University Press, 2003)

[26] O’Donoghue Papers, MS 31,233

[27] O’Malley, Galway Interviews, p. 212

[28] Ibid, Kerry Interviews, p. 62

[29] Ibid, p. 64

[30] Ibid, p. 319

[31] O’Donoghue Papers, MS 31,237(2)

[32] UCD, Martin Conlon Papers, P97/16(1)

[33] Ibid, P97/11(i)

[34] O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin: Anvil Books, 1986), pp. 194-5

[35] O’Donoghue, Florence (edited by Borgonovo, John) Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence: A Destiny That Shapes Our Ends (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2006), pp. 58-60

[36] Deasy, Liam (edited by Chisholm, John E.) Towards Ireland Free: The West Cork Brigade in the War of Independence 1917-21 (Cork: Royal Carbery Books, 1973), pp. 258-9

[37] O’Malley, West Cork Interviews, p. 190

[38] Deasy, pp. 15, 258-9

[39] O’Malley, Kerry Interviews, p. 138

[40] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Óg Ó Ruairc, Pádraig) The Men Will Talk to Me: Clare Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2016), pp. 155-7

[41] O’Malley, Kerry Interviews, pp. 303, 305, 319

[42] O’Malley, Interviews with the Northern Divisions, p. 179

[43] McKenna, pp. 44-6

[44] O’Malley, Kerry Interviews, p. 281

[45] O’Meara, Seumas (BMH / WS 1504), p. 53

[46] O’Brien, Henry (BMH / WS 1308), pp. 23-4

[47] Daly, David (BMH / WS 1337), p. 28

[48] O’Connor, Frank (BMH / WS 1309), p. 28

[49] Conlon Papers, P97/18(ii)

[50] Regan, John M. Myth and the Irish State (Sallins, Co. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, 2013), p. 126

Bibliography

Newspaper

Irish Times

Books

Deasy, Liam (edited by Chisholm, John E.) Towards Ireland Free: The West Cork Brigade in the War of Independence 1917-21 (Cork: Royal Carbery Books, 1973)

Fitzpatrick, David. Harry Boland’s Irish Revolution (Cork: Cork University Press, 2003)

Griffith, Kenneth and O’Grady, Timothy. Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1998)

O’Donoghue, Florence (edited by Borgonovo, John) Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence: A Destiny That Shapes Our Ends (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2006)

O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin: Anvil Books, 1986)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Aiken, Síobhra; Mac Bhloscaidh, Fearghal; Ó Duibhir, Liam and Ó Tuama Diarmuid) The Men Will Talk to Me: Ernie O’Malley’s Interviews with the Northern Divisions (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Merrion Press, 2018)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Bielenberg, Andy; Borgonovo, John and Óg Ó Ruairc, Pádraig) The Men Will Talk to Me: West Cork Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2015)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by Óg Ó Ruairc, Pádraig) The Men Will Talk to Me: Clare Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2016)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Horgan, Tim) The Men Will Talk to Me: Kerry Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Comhraí, Cormac) The Men Will Talk to Me: Galway Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

Regan, John M., Myth and the Irish State (Sallins, Co. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, 2013)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Daly, David, WS 1337

McKenna, Seamus, WS 1016

O’Brien, Henry, WS 1308

O’Connor, Frank, WS 1309

O’Meara, Seumas, WS 1504

Military Archives – Cathal Brugha Barracks

Michael Collins Papers

University College Dublin Archives

Martin Conlon Papers

Richard Mulcahy Papers

National Library of Ireland

Florence O’Donoghue Papers

The first point is a peculiar one as there had been nothing in Barry’s letter about attempts among the Anti-Treatyites at forming a counter-IRB. It is possible that Mulcahy had heard about the musings of Liam Lynch, the IRA Chief of Staff, about reforming the IRB Supreme Council, and the Brotherhood in general, along Anti-Treatyite lines.

The first point is a peculiar one as there had been nothing in Barry’s letter about attempts among the Anti-Treatyites at forming a counter-IRB. It is possible that Mulcahy had heard about the musings of Liam Lynch, the IRA Chief of Staff, about reforming the IRB Supreme Council, and the Brotherhood in general, along Anti-Treatyite lines. This was more than mere thoughtless but part of a glass-ceiling policy. As he described later in his memoirs, Ó Muirthile did not think it wise to be indiscriminate in the shaping of the new Brotherhood. This cartel within a cabal soon led to resentment among those on the outside, a simmering discontent that would have ruinous consequences for all concerned.

This was more than mere thoughtless but part of a glass-ceiling policy. As he described later in his memoirs, Ó Muirthile did not think it wise to be indiscriminate in the shaping of the new Brotherhood. This cartel within a cabal soon led to resentment among those on the outside, a simmering discontent that would have ruinous consequences for all concerned.