A continuation of: Plunkett’s Gathering: Count Plunkett and His Mansion House Convention, 19th April 1917 (Part IV)

The Rift

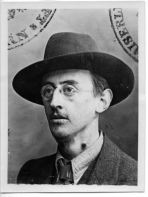

There was a pause in the hall as Arthur Griffith conferred with Count Plunkett on stage. Griffith then stepped forward to announce a troubling development.

Plunkett, he said, had denied him permission to speak. He had wanted to explain his reasons for seconding Seán Milroy’s proposal – which had called for a loose alliance between the various separatist groups, as opposed to the Count’s demand for a new, centralised organisation – but that was not going to happen now.

“I have nothing further to say than this,” Griffith told his audience, and proceeded to speak further. “Sinn Féin, for which we all stood when many of the men here today were our opponents, still stands. Sinn Féin will not give up its policy nor its constitution. Sinn Féin will work with every section in Ireland that works to destroy the corruption of Ireland.”

He finished on a note of J’accuse: “I am finished. Count Plunkett refused me permission to speak.”

To a mixed chorus of cheers and boos, Griffith told his audience of how for eighteen years he had been fighting for the cause of Irish freedom. If he lived for eighteen more, he would still be fighting. He warned that if they decided today not to hold an alliance against John Redmond and his Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), then Redmond would win as surely as he, Griffith, was standing before them.

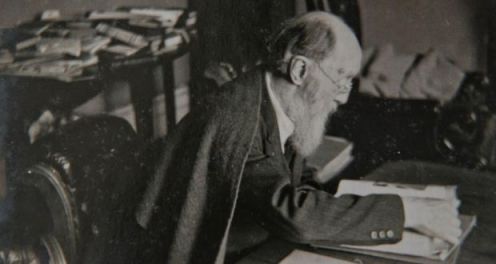

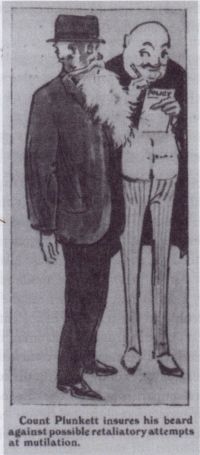

Adopting an air of being above it all, Count Plunkett said he had no intention of commenting on these accusations. He had never misrepresented Griffith, and he had heard no misrepresentations of him. Why Griffith felt the need to defend himself against nothing was rather puzzling, Plunkett added primly.

Pulling back somewhat from his previous hard-line stance, Plunkett said that there was no reason why, in the coming elections, men who did not see eye to eye on everything could not unite to pull down the common foe in the IPP. The nation was above personal quarrels and petty disputes.

It was a magnanimous line, one worthy of the statesman Plunkett clearly believed himself to be. Dissenting calls of “why did you refuse to hear Arthur Griffith” and “a good many of us here are not in favour of that at all” showed that for some, however, the Count’s munificence was not convincing.

A Way Out?

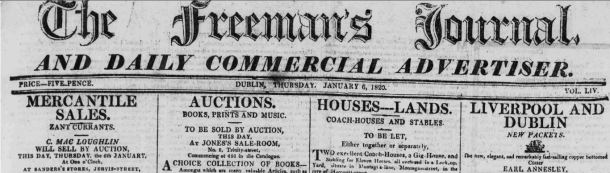

This turn of events, as reported in the Freeman’s Journal:

…led to much excitement, and those on the platform rose to their feet and conversed – in some cases very heatedly – in small groups, while murmurs of protest throughout the room testified that opinion was divided on the action taken.[1]

Attempting to gain some ground in the tug-of-war being played out, Milroy moved that his proposal be put to the convention, insisting that it did not clash with Count Plunkett’s own. It is questionable as to whether Milroy actually believed this. Count Plunkett certainly did not. He replied that, au contraire, Milroy’s resolution *did* clash with his.

At best, a stalemate seemed inevitable at this point; at worst, open hostilities and a split.[2]

William O’Brien, the Labour delegate from the Dublin Trades Council, was seated by the podium, having little input in the proceedings after delivering his speech (he had only attended in the first place to be polite, he later said). He belatedly realised there was a commotion between Plunkett and Griffith happening before him, though he was unclear as to its cause, and watched as Father Michael O’Flanagan moved across the platform to sit next to a “flushed and evidently upset” Griffith.[3]

The enmity between the two leaders had been festering for quite some time. According to Laurence Nugent, a close friend of Rory O’Connor – who Nugent accredited with most of the Convention’s organising – the Count had refused to send admission tickets to Griffith and Milroy, forcing Father O’Flanagan to take two spare tickets from the mantelpiece of Plunkett’s house.[4]

Plunkett’s daughter, Geraldine Dillon, told a different version. Her father had indeed invited Griffith who refused until Tommy Dillon, her husband and the Count’s son-in-law, persuaded him otherwise. Even then, Griffith had not endeavoured to make things easy, sitting sulkily at the back of the hall. When he made to leave after locking horns with the Count, it took the entreaties of O’Flanagan and another priest, Father William Ferris from Kerry, to convince him to stay.[5]

Coming to Heel

As a way out of the impasse, Father Ferris suggested that these questions be left in the hands of Father O’Flanagan and Griffith. This at least was met with general approval. If Plunkett felt to the contrary, he kept his opinion private for a change. He did, after all, owe a lot to O’Flanagan. “The old man came to heel,” sneered Kevin O’Shiel, as he remembered it.[6]

O’Flanagan announced that, after discussing with Griffith, it was agreed that an organising committee be formed. Those national groups pledged to Irish independence should get in touch with this committee and apply to be recognised. Likewise, all the new branches of these various groups that formed as a result of this convention should contact the committee.

The members of this committee were to be – besides the Count, Griffith and the ubiquitous Father O’Flanagan – Milroy, Dillon, Tom Kelly and Stephen O’Mara. O’Mara had already enjoyed a lengthy political career as the mayor of Limerick and a Parnellite MP in Co. Laois. Along with the rest of the Irish Nation League, of which he had been a founding member, he had disagreed with Plunkett’s decision to abstain from his Roscommon parliamentary seat.

Tom Kelly was one of the founders of ‘old’, pre-1916 Sinn Féin and had worked in a number of public positions, from an alderman in Dublin Corporation to campaigning in the 1880/90s on behalf of imprisoned Fenians. O’Mara, Kelly and Milroy could be expected to back Griffith, with Dillon and O’Flanagan more inclined towards the Count.[7]

According to O’Brien, O’Flanagan read out the names before asking Griffith to second them. Griffith said that while he had no objections, surely Labour should have a voice as well? For this, he slyly suggested O’Brien as another member, clearly considering him to be an ally.

Thinking quickly, the priest replied that he had no problem with O’Brien, whom he did not know but was sure to be a decent sort. But if Labour was to be included, then so should the women of Ireland. For this, he proposed Countess Plunkett, sitting by the stage near her husband.

Having stopped the tensions from escalating, Father O’Flanagan was taking no chances with the Committee numbers being stacked in Griffith’s favour. More than anyone, he had been responsible for bringing the new movement together, and he was determined to keep it that way.

O’Brien, for his part, was to plead ignorance of the manoeuvrings unfolding before him:

For a portion of the meeting I had no idea what was going on and a great many people couldn’t know and I thought the whole business was the nearest thing you could imagine to a break-up.[8]

There seems to have been some confusion in the sources over the exact composition of the committee. O’Brien neglected to mention Tom Kelly but included Cathal Brugha, as did Geraldine Dillon in her memoirs. On the other hand, the Freeman’s Journal – a contemporary and the most comprehensive account of the Convention – made no mention of Brugha.[9]

However, New Ireland, the organ of the Irish Nation League, named him as being on the committee in its 28th April edition, so it seemed that Brugha had made his way in at some point. A militant Republican and a combatant in the Rising, during which he had been seriously wounded, his inclusion was a boon to Plunkett, and he would come to take a leading role in the factional negotiations that were to come.[10]

(Another version was from Dillon’s account. Here, Helena Molony, the feminist and socialist, objected to the absence of a woman on the committee. Father O’Flanagan obliged by adding her and Countess Plunkett. No one else mentions Molony at this point, not even Molony herself, so this seems to be incorrect on Dillon’s part. Molony was later co-opted, along with three other women, onto the Sinn Féin Executive Committee in October 1917, which could explain Dillon’s confusion.[11])

The Plunkett Convention had been a lengthy, and for some gruelling, event, having taken most of the day. Much had been agreed upon, but the Plunkett-Griffith enmity was to be the most remembered aspect. One attendee was to describe it in suitably dramatic terms:

Almost from the moment that the meeting opened, antagonism to Griffith was shown by Count Plunkett…Such as Count Plunkett’s apparent anger that a serious disturbance arose on the platform. I think everyone at the meeting expected that those on the platform would be utterly divided…Griffith was regarded as a pacifist at that time, and Count Plunkett was obviously out of patience with him from the moment he saw him on the same platform.[12]

Which was not entirely correct – the Convention had managed for some time before the said disturbance arose. Still, there could be no hiding the unpalatable fact that the new movement was already poised to be at war with itself.

Somehow, the day managed to end on a cordial note when Count Plunkett announced the closing of the proceedings, with the reminder that they would be called again if needed. History was on the march, and there was no certainty as to where it would lead.[13]

Surveying the Aftermath

In the days afterwards, the Mansion House hosted a gift sale that was to raise funds for the families of those in the Rising. The choice of items on display, and the swiftness in which they sold, showed that the presence of 1916 was as keenly felt as ever:

- An ancient Irish costume, worn on one occasion before Pope Pius X by Éamonn Ceannt.

- A gold-mounted fountain pen, presented by Ceannt’s widow.

- A pair of gloves worn by James Connolly.

- An Irish pike-head which had belonged to Michael Joseph ‘The O’Rahilly’, slain during the fighting in Dublin.

- A pocket flask belonging to Éamon de Valera, presented by his wife.

- A first edition of poems by W.B. Yeats, with an autograph by Joseph Plunkett.

- The sword which had fatally wounded Lord Edward FitzGerald in 1803, formerly owned by Patrick Pearse.

- A handbill of the ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’.[14]

As someone who prided himself on keeping his ears close to the ground, Monsignor Michael Curran lingered around the Mansion House. From the talk he picked up on, reactions to the Convention had definitely been positive, as he later described:

While Plunkett was not regarded as a suitable leader or director, it was felt that the new organisation would bring the groups together and that the general body of public opinion would follow Arthur Griffith and that Griffith’s policy of working with the less advanced Nationalist sections was correct.[15]

The situation, however, was a good deal more complicated than that, as not everyone believed that Griffith’s approach was the right one.

Another attendee, Liam de Róiste, had come as a delegate for the Cork Sinn Féin Executive. He found that while Count Plunkett lacked general support, Griffith’s policy of passive resistance to British rule was not sufficiently exciting for the more impatient types in the audience. That Griffith was rumoured to have been opposed to the Rising at the time, for all his subsequent reaping of the benefits, also counted as a black mark against him.[16]

Count Plunkett had succeeded in getting his motion passed for a new, centralised organisation. He had also managed to shut Griffith up, at least for a while. But, outside the convention, this did not mean very much. At the end of the day, neither man had scored a definite victory over the other. Their feud, and its potential for damage, remained unabated.

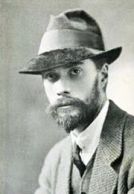

To Griffith, Count Plunkett was a hot-headed upstart who was trying to both usurp and wreck the Sinn Féin party to which he had dedicated his life. To Plunkett, and the hard-liners who backed him, Griffith was a has-been who blew neither hot nor cold but unacceptably lukewarm.

Committee Politics

The forming of the Mansion House Committee, as timely as it had been in preventing an irreversible rupture, could be little more than a stopgap. Much to his displeasure, O’Brien was to find himself on the frontlines of the feud. In keeping with his reluctance to become embroiled in Nationalist politics at the possible expense of Labour, he tried talking himself out his new duties. Even a lengthy chat with Griffith, who pleaded with him to remain, was not enough to change his mind.

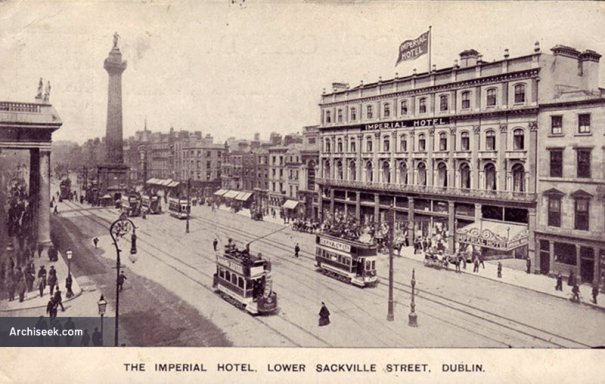

When O’Brien was asked by Milroy to attend the first meeting of the new committee at the Gresham Hotel on the 3rd May, O’Brien declined. When Milroy pressed O’Brien to come and explain his reasons in person, at least as a courtesy to Griffith, the trade unionist reluctantly submitted.

And so O’Brien arrived at the Gresham with Milroy, finding the rest of the committee already present. As they went upstairs, Griffith gave O’Brien a nudge:

Griffith: We want you to preside at this meeting.

O’Brien: Oh, that is quite impossible. I can’t act on the committee.

Griffith: Oh. You ought to act for the present anyhow. There is no way out. Stephen O’Mara will propose you.

When they were in the allocated room, O’Flangan said: “Now, we want a chairman.”

Plunkett appeared taken aback by this. Before anyone else could speak, O’Mara proposed O’Brien, right on cue, and O’Brien found himself as the chair. Even if Griffith had no interest in power for himself, he was still determined to deny it to his bitter rival.[17]

The Liberty Clubs

Count Plunkett had called for a new organisation, one that would be primed to advance the cause of Irish freedom – on his own terms, that is. Others would answer that call throughout the country, with Co. Cork providing a microcosm of the new political enterprise and its budding grassroots.

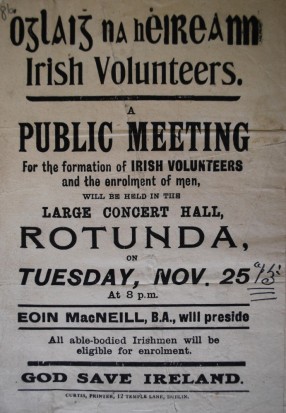

On the 11th May, Hugh Thornton wrote from Bandon, Co. Cork, about the interest he had received from like-minded individuals. He had formerly been of the ‘Kimmage Garrison’ at the Rising that had been under the command of the Count’s son, George. Thornton explained that he had only been in Bandon for a fortnight but had nonetheless impressed the “right men” of the importance of forming a branch of the Liberty Clubs, which was what Plunkett’s brainchild would become known as.

Thornton had attended the conference the month before and knew the main objectives. Nonetheless, he pressed upon the Count the importance of receiving the necessary paperwork to put before the respective recruits before he could convene a first meeting.[18]

Six days later, on the 21st May, Thornton wrote back to confirm that he had received the copies of the rules and constitution of the Liberty Clubs as requested. A Club had been formed accordingly in Bandon, encompassing fifteen members and with more expected.[19]

Thornton had spoken truly, for by the 26th, he felt it necessary to write again, asking for fifty more membership cards and a hundred copies of the constitution. The success of the Club in Bandon had stimulated interest in nearby Castlelake, where there were plans to start one of its own.[20]

Later, a letter from the committee of the new Liberty Club in Castlelake was received on the 4th June, asking for thirty membership cards. It was addressed to Count Plunkett as president, with a question mark at the end of the title, suggesting an uncertainty as to how the organisation was structured.[21]

The Clubs Take Root

Thornton wrote to ask Plunkett if they could have a talk when the latter visited Cork on the 19th June, specifically so he could report on the local conditions. He also asked more mundane questions such as whether duplicate membership cards should go to Plunkett or if the Club secretaries (which Thornton was for his own group) should hold onto them. It was the sort of nuts-and-bolts decisions that make up the growth of every fledgling movement.[22]

Others expressed similar interest. Cornelius O’Mahony wrote from Ahio Hill, Co. Cork, to say that while there were no clubs around due to the isolated nature of the area, he was optimistic that any organisers sent out there would have an impact, if only because the sight of a stranger was a novelty in itself.[23]

John Linehan from Tullybase, Co. Cork, told Plunkett that he would be all too happy to render assistance. He shrewdly suggested that if the parish priest was also to help, then the Club would be a success. Tullybase was fertile ground, Linehan assured the Count, as “the great majority of the people here are all Sinn Feiners, and followers of the Irish Party were always few.”[24]

Linehan clearly did not think that a Liberty Club would be incompatible with Sinn Féin. Others were not so sure. P. Casey felt the need to ask the Count if there was any difference between the two organisations. He added that he was in a “splendid position for collecting names of the right-type of men” due to his position as a barber in Cork City.[25]

Linehan clearly did not think that a Liberty Club would be incompatible with Sinn Féin. Others were not so sure. P. Casey felt the need to ask the Count if there was any difference between the two organisations. He added that he was in a “splendid position for collecting names of the right-type of men” due to his position as a barber in Cork City.[25]

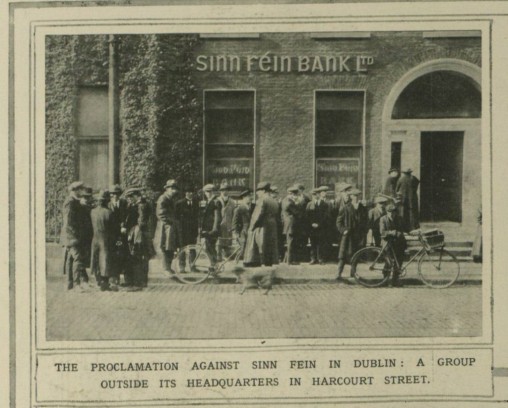

Elsewhere in the country, the existence of Sinn Féin was a stumbling block for the Clubs. Timothy Flanagan told of how there was no Liberty Club in Killinaboy, Co. Clare, as everyone there was already part of the older organisation.[26]

Likewise, James Connaughton believed that since Sinn Féin was already established in Limerick, attempts to form a Club would risk a clash. However, Connaughton had not given up hope that a Club could be set up and suggested that the process might be eased if some joint plan of action was arranged between the two separatist groups.[27]

Others were not so optimistic. The Cork Sinn Féin Executive delivered a warning on the 22nd May that “if our forces are split up into possible rival organisations it will have a disastrous effect upon the whole movement.” In order to prevent this fracturing, the Executive claimed the right to direct matters in its city without outside interference.[28]

Teething Troubles

Hugh Thornton would never get a chance to talk with Plunkett, for the latter was to cancel his planned visit to Cork. In a letter to the Cork Examiner, the Count explained that his reasons for doing so were because the situation was not yet right:

The purpose of the gathering was not for a mere personal compliment, but to thoroughly organise the city and county of Cork – to move Munster and bring it to the front in Ireland’s struggle for complete independence.

I defer meeting the people of Cork for the present, because the workers at the head of the advanced movement are at this moment considering the means of welding the strong national bodies into one organisation, with one administration. Irish opinion cannot become the power it should be until its combined forces are wielded as one instrument to a common end.

I am certain that the formation of Liberty Clubs and other clubs differing in name, but working equally for the advanced cause, will be actively promoted at once, so that Cork may take its share in our united effort to open the road to freedom.[29]

The Cork Examiner took a less sanguine view, reporting that:

It is now admitted but there is a split in the Sinn Fein camp between those who favour Count Plunkett and those whose allegiance goes to Mr Griffiths resenting Count Plunkett’s visit to Cork put pressure on headquarters, and Count Plunkett has now cancelled his visit.[30]

The newspaper was far from an unbiased source, being a supporter of the IPP and thus hostile to its patron’s rivals. But Laurence Nugent, by now a full time organiser for Sinn Féin, suspected that Plunkett’s refusal to attend Cork was due to the Sinn Féin people there being of the old, pro-Griffith adherents who did not want him.

Nugent would remember an exasperated Father O’Flanagan complaining privately to him about how the Mansion House Committee could never agree on anything. At least the general public took it for granted that progress was being made, even if uncomfortable rumours were circulating within Sinn Féin circles of how just hollow the public façade of unity really was.[31]

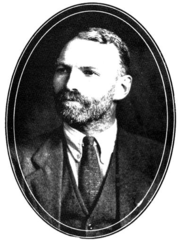

William O’Brien

The situation was such that, on the 5th June, O’Brien was called on by a delegation from the Cork Volunteers. They explained to him that there was dissatisfaction back home regarding the confused situation with the Liberty Clubs and where they stood with Sinn Féin. In an attempt to clarify matters, they had been dispatched to Dublin to interview a number of individuals, who had suggested that they talk to O’Brien.

He had by then resigned from the Mansion House Committee, whose membership he had never wanted in the first place. Still, as an avowed Republican, he was seen as a sympathetic ear by the Volunteers. O’Brien was friendly with both Plunkett and Griffith, but told the Corkonians that, in his opinion, neither man counted for much.

The Irish Volunteers, O’Brien told his guests, were the only body in the country which could see the ideals of the Easter Rising realised. If they wished to accomplish this, then they should make their views known to both the Count and Griffith. O’Brien added that if the two men refused to come around to their point of view, then the Volunteers should simply brush both aside and act on their own.

Efforts towards public unity had been made in May, when the by-election in South Longford provided the chance for Plunkettites, Volunteers and Sinn Féiners to campaign together on behalf of their candidate, Joseph McGuinness, against the IPP selection. However much they distrusted each other, they could at least agree to dislike the Irish Party even more.

McGuinness’ success on an absentionist ticket – the second such win that year after Plunkett’s in North Roscommon – was satisfying but did nothing to assuage the tensions. Shortly afterwards, the election committee met to consider whether it should be established as a permanent organisation under the title of ‘The Irish Freedom Election Committee’.

Although Griffith did not say so openly, it seemed clear to O’Brien – who still attended such meetings despite his resignation – that Griffith was opposed to this proposition, stealing as it would the attention away from Sinn Féin. However, he departed early, allowing the others in his absence to agree to this latest development – not the best way, perhaps, for an already fragile group to make decisions.

A further meeting of the election committee was held on 30th May at which Griffith again questioned its necessity. Another lengthy discussion followed, punctuated by a sharp exchange between him and Count Plunkett.

Meanwhile, a public rally at Beresford Place, Dublin, was set for the 10th June to protest at the conditions in which the Rising prisoners were held in English jails. When the authorities proscribed the meeting, its organisers agreed for it to be postponed.

Agreed by all, but one. O’Brien was very much surprised upon learning that Plunkett was going ahead with the meeting, regardless of what the others had decided.[32]

Trouble at Beresford Place

Perhaps Plunkett’s contrariness was motivated by the reports of the treatment of his sons, George and Jack, in prison, from the scanty amounts of poor quality food to homosexual rape, which their sister Geraldine “knew afterwards from Jack’s nightmares, did happen.”[33]

Or maybe it was out of desire to buck both the British authorities and his ‘colleagues’. Either way, people in the streets of Dublin on the morning of the 10th June were handed leaflets on their way from church by a number of young men and women. Headed ‘Strike in Lewes Jail’, the handbills notified their readers of the time and place of the meeting: 7:30 pm at Beresford Place.

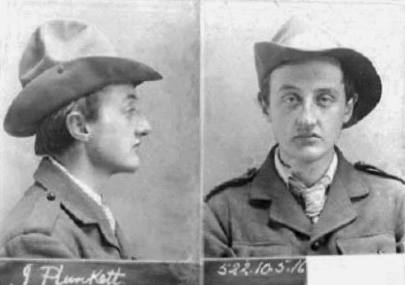

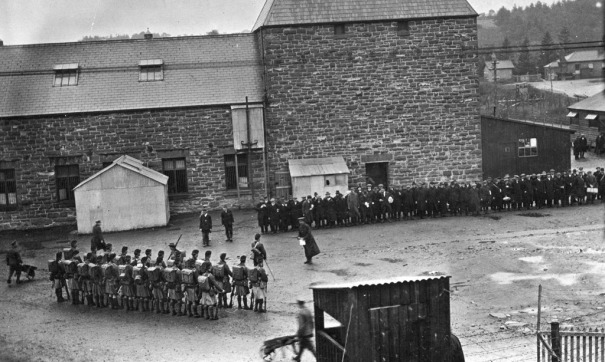

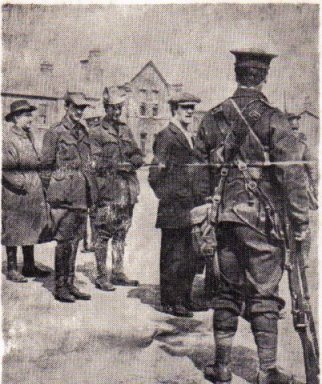

Such brazen publicity also alerted the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) were also alerted, a squad of which was being present at Beresford Place by the advertised time. Meanwhile, a 200-strong crowd made its way across Butt Bridge from the south side of the Liffey River. At the back of the procession was a hackney car with Plunkett and Brugha inside.

When the crowd reached Beresford Place, the car pulled up in front of Liberty Hall. Inspector John Mills pushed his way at the head of a police party through the press of bodies and ordered Brugha to get down from the top of the car on which he was addressing the crowd. When Brugha persisted in speaking, Mills pulled him down while, on the other side of the car, Plunkett was likewise arrested.

The mood of the onlookers turned ugly at the sight of their heroes being manhandled, and the policemen found themselves being followed as they led their prisoners away. The DMP sergeant with Plunkett advised him to hurry along for fear of trouble. Seeing the milling, agitated people all around, with the potential for violence heavy in the air, the Count agreed by quickening his pace.

Arrested

As the police passed underneath the railway arch at Beresford Place, a young man stepped forward. Without warning, he struck Inspector Mills on the back of the head with what witnesses described as a hurling stick.

Constable John Dooley grabbed the assailant by the collar as the latter turned to escape. The crowd closed in on them and Dooley received a blow to the head in turn, driving him to his knees as he doggedly held on. The culprit finally wriggled free and ran down Lower Abbey Street, turning at one point to brandish a revolver at Dooley, before disappearing out of sight.

Meanwhile, Superintendent Brennan was leading another police party in pushing the unruly mob back by Eden Quay. When he heard a shout of “The Inspector is killed”, he ran to find Mills on the ground, blood oozing from his left ear.

After casting some stones, the crowd dispersed, its energies spent. In addition to Plunkett and Brugha, three more had been arrested: the cabdriver who had brought them, a youth for drawing a dagger and a stone-throwing man. The prisoners were taken to Sloane Street Station, before transferred to Arbour Hill the following night.

Mills had been driven to Jervis Street Hospital, where he died of shock and haemorrhaging from what the doctor described as the worst injury he had seen in his professional career. The 51-year-old native of Co. Westmeath left behind a widow and three children. According to Geraldine Plunkett, her father had said upon seeing Mills collapse: “Oh, the poor man! I hope he’s not hurt.”

It says much about the relative obscurity of Brugha at the time that he was “a man named Burgess” and “a man who gave his name as Cathal Burgess” when the Irish Times reported him alongside the far better known Count Plunkett.[34]

Despite talk of those arrested being tried for the murder of Inspector Mills, they were released from Arbour Hill on the 18th June as part of the general amnesty for political prisoners. This include the remaining inmates from the Rising, and the Count’s two sons were discharged accordingly, finally returning home after almost a year of imprisonment.[35]

‘Hot and Strong’

The British authorities were not the only ones attempting a diplomatic solution. It was clear that the divide between Sinn Féin and the Liberty Clubs, rapidly deepening into a split, could not continue.

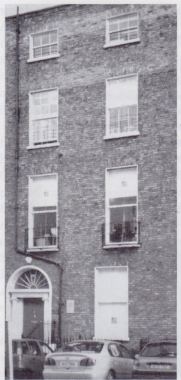

So far, the upper hand was held by Sinn Féin. The Liberty Clubs were hampered by the lack of public association with the Rising which Sinn Féin possessed, however undeservedly, and the absence of a central office to which to send the all-important affiliation fees – another advantage Griffith enjoyed. Instead, correspondence for the Liberty Clubs were sent to and from the Count’s residence at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street, creating a slightly ramshackle feel, as if the man who was one of the country’s best-known political figures could manage no better.

Despite these drawbacks, Dillon could observe how the Liberty Clubs were:

…making progress and stories began to reach us of Sinn Féin Clubs and Liberty Clubs in the same parish. They were by no means on friendly terms with one another. The Royal Irish Constabulary [RIC] were quick to take advantage of the reputation of Sinn Féin to stir up trouble. ‘So ye’re afraid to call yourselves Sinn Foeners’, they would say to members of Liberty Clubs.[36]

Trouble was astir, indeed. The monthly report of the RIC Inspector General in May speculated on how the movement:

…may divide into two sections, a revolutionary party under the leadership of Count Plunkett, and another and perhaps more numerous party, who realising the futility of armed insurrection, will try to achieve their aim by more passive measures.[37]

Before matters could get to that point, an attempt at resolution was held in Brugha’s house in Upper Rathmines Road, a courtesy made on account of his still-healing leg wound from the Rising. Despite his slightly debilitated state, Brugha would take up the role of advocate for hard-line Republicanism, proving in the process to be a far more forceful character than Count Plunkett.

Dillon could not remember precisely who was in Brugha’s house that evening, though the conclave included his father-in-law, Griffith, Michael Collins and Rory O’Connor, as well as some other members of the Mansion House Committee. Nor could Dillon recall the resulting conversation exactly – it was not until 1967 that he put his account to paper – other than it had been “hot and strong, without being too acrimonious.”

Griffith was asked, or rather told, to hand over control of Sinn Féin to the Irish Volunteers. He held his ground, insisting that Sinn Féin would not surrender the name he had spent years toiling to build. Furthermore, he added, he had been elected president by a Sinn Féin convention and so could only hand over the role to someone elected at another such convention.

Walking the Plank

As it was getting late and the last trams home were due, Dillon summed up their options: to found a new organisation – as had been proposed at his father-in-law’s convention – or to reform Sinn Féin on conditions to which Griffith and the Plunkettites would find acceptable. Dillon added that the second was the simplest.

Sensing the support for this in the room, Griffith changed tact. He agreed to put before the Sinn Fein National Council the proposal that half of them would retire to make room for six representatives of the Liberty Clubs and the Mansion House Committee. Dillon would be joint honorary secretary along with the current one, with the president and his paid officials remaining unchanged until the next party Ard Fheis, set for October. Soon after, Dillon received a note to say that the National Council had agreed to these terms.[38]

It was a gracious retreat on Griffith’s part, though perhaps he had had little choice.

O’Brien learnt from Brugha, with whom he had grown close, of the compromise arrangements decided upon in the latter’s house. When O’Brien was told that the new constitution for Sinn Féin would include the recognition of the Republic as proclaimed in the Rising, O’Brien was surprised. He did not think Griffith – a cautious man by nature – would go so far on such a charged point.

“Do you mean that Griffith has accepted the Republic?” O’Brien asked.

“He had to or walk the plank,” answered Brugha grimly.[39]

Hard Truths

Even Griffith’s allies had accepted that a surrender on his part was inevitable. From listening to the Sinn Féin branch meetings, Seán T. O’Kelly came to the conclusion that the ‘military’ men in the movement – those who had taken part in the Rising – would never accept Griffith as their leader. But Griffith still had his friends and admirers, even among said ‘military’ men, who disliked the idea of deposing a man who had done such sterling work for the country over the past twenty years.

With this conundrum in mind, O’Kelly was one of several men who went to Alderman Walter Cole’s home in 3 Mountjoy Square on the 24th October, the night before the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis was due. Cole told them that he had taken the liberty of asking Griffith to come along as well.

By the time Griffith arrived, the others had arrived at an unhappy but inescapable conclusion: should he run again as Sinn Féin president, he would be defeated. It would thus be best to retire gracefully. It fell to Cole to inform Griffith of this collective opinion.

Griffith took it in good stead. After talking it out with the others for half an hour with what O’Kelly considered to be admirable dispassion, Griffith told them that he would give their advice serious consideration. His decision would be announced the next day. It was the most Griffith was prepared to concede at that point, and his friends did not press it.

Such talks and manoeuvrings had been largely kept hidden from the majority of delegates who lined up outside the Mansion House to have their passes checked by the Irish Volunteers posted on the doors. It was soon apparent that the Ard Fheis would be a packed one. Half an hour before the opening and the Round Room inside was already crowded, with more guests continuing to stream in at a steady pace.

It was stated by party officials that 1,700 delegates, representing 1,009 Sinn Féin clubs throughout the country, were present. But in the opinion of the Freeman’s Journal – no friend of radical politics otherwise – the actual numbers far exceeded this estimate.[40]

‘A Soldier and a Statesman’

Count Plunkett and his wife were among the early arrivals. As the proceedings began, Éamon de Valera and W.T. Cosgrave, the Members of Parliament (MPs) for East Clare and Kilkenny City respectively, stepped on the platform, followed by Griffith. Beneath the applause that greeted each man, the excitement and anxiety were acutely felt by all.

The Plunkett Convention six months ago, held in that very same hall, had showed that even in the heart of the movement’s power and display, a split was not impossible. Given the simmering tensions since then, it was not even implausible.

This time, the risk centred on the three candidates for the presidency. In the opinion of Kevin O’Shiel, Griffith was the obvious choice. He was, after all, one of the founders of Sinn Féin as well as the current office holder. But his openness to an Ireland continuing under the British Crown as part of some dual monarchy idea of his, and his initial opposition to the Rising, made him anathema to many.

As for Count Plunkett, he was more distinguished by his sons than his own qualities. That had not stopped him from attempting to take central stage in the movement. Despite having canvassed for the Count in the momentous by-election earlier in the year, O’Shiel soon resented the sense of entitlement:

Since his big victory in [North] Roscommon, he and his supporters had come to regard him as the predestined leader of the Irish people on whom “the mantle of Elijah” had fallen, charged with the definite leadership of the country in the new struggle.

Whatever the doubts of O’Shiel, Griffith and others, Plunkett could rely on the Republican elements for support. But the Liberty Clubs, intended to be his powerbase, had not been able to replace Sinn Féin as Plunkett had hoped, largely due to their failure to overtake Sinn Féin in the public mind as the originator of the Rising. It was on this critical factor that politics in the post-1916 Ireland would rise or crumble.

The third contender, de Valera, was the dark horse in the race. Despite the lack of fame as enjoyed by the other two, he did possess certain advantages. His record as a Rising participant, and a senior officer in the Irish Volunteers at that, bestowed credibility of the sort Griffith could never attain. At the same time, de Valera made it clear that he had arrived at his Republican position by his belief that that was what the Irish public wanted, an open-mindedness which reassured moderates that here was someone they could work with.

When the subject of the presidency came up, a hush fell over the room. Everyone tensed to see what would unfold. A minute ticked by, feeling like an hour. Then Griffith rose and, to the surprise of many, announced that he was not putting himself forward. He thereupon withdrew his nomination, declaring instead for de Valera, in whom, Griffith informed his audience, “we have a soldier and a statesman.”

The resulting applause went on for some minutes, due in no small part to the relief that a split had just been avoided. Obviously following the same script, Count Plunkett also withdrew, ensuring that de Valera’s election as the new President of Sinn Féin was a unanimous, not to mention mercifully uneventful, one.[41]

The New Leadership

Not that this had been entirely unexpected. The night before, de Valera had come to talk to Kathleen Lynn and Helena Molony, both as Labour representatives. After informing them he was being put forward as a compromise between Plunkett and Griffith, he asked if that would be acceptable. The two women agreed, and Molony was much satisfied with the arrangement. They had kept out Griffith, whom she despised for his moderation. While she had supported Plunkett, that had been for the sake of his martyred son, Joseph, and not so much for him. In terms of leadership quality, she found de Valera to be by far the better choice.[42]

The new Sinn Féin Executive that emerged from the Ard Fheis bore little resemblance to the ones of the past ten years. Those few ‘old’ party hands who remained on the twenty-four-strong body did so because they, like the rest, had some connection to the Rising. From then on, the course of the party would be guided by its militants.[43]

Seeing where the wind was blowing, both the Liberty Clubs and the Irish Nation League folded and amalgamated into Sinn Féin, ensuring that the party would be a ‘broad church’, reflecting both hard-line and moderate opinions. In truth, it was not now dissimilar to the IPP in the past, which had had room for constitutionalists like Charles Stewart Parnell and John Redmond, as well as former Fenians such as Michael Davitt and James J. O’Kelly, the late MP for North Roscommon who Count Plunkett had succeeded.

With Sinn Féin set to defeat IPP come the next election, the new had replaced the old in more ways than one, though few in the reformed Sinn Féin were inclined to appreciate the historical repetition. A line had been drawn in the sand, and a break made with the past. The days of compromise were over, or so those in the Ard Fheis told themselves.

The End

Both Griffith ad Plunkett were consoled for their self-denial of the presidency with the elections of the former as one of the dual Vice-Presidents (Father O’Flanagan being the other) and the latter to the twenty-four-strong Executive Council. This may have been the point in which the Count actually joined Sinn Féin. He had been content to have it campaign on his behalf in North Roscommon but at his April convention he had been markedly hostile, determined to have the party replaced with one more to his liking.

Not that this had stopped him from being a contender for the Sinn Féin presidency. It says much about the confusion and fluidity of the times that one action did not necessarily negate a contradictory other.

Many had gone into the Ard Fheis fearing a split between Griffith and Plunkett. Instead, Sinn Féin had been able to retain both men. Whether by accident or design, the top echelons of the party upheld a balance between the two opposing viewpoints in the movement – the constitutional and the militant – a difference which would be, if not conciliated, then at least pacified…for long enough, at least.

Not that the two men would ever completely bury the hatchet. Five years, in March 1922, Griffith was speaking to the Dáil when Count Plunkett made, according to the Irish Times, “an observation which was imperfectly heard.”

Whatever was said, Griffith did not assume it to be favourable towards him. He responded by saying that he had been campaigning for the rights of Ireland at a time when Plunkett was receiving the King of England and hanging out flags (which were presumably Union Jacks).

“I did not pull down the Irish flag,” said Plunkett, who seems to have misheard somewhat.

Griffith did not let up, insisting that the other man had received the King in Cork – a reference to the 1903 Exhibition, which Plunkett had helped supervise – when he had sworn allegiance to the visiting Edward VII.

“I never swore allegiance,” Plunkett protested.

“Maintain the dignity of the Dáil,” said Brugha, intervening in defence of his friend.

“Keep this man from interrupting,” Griffith retorted. “I will not be interrupted by a humbug.”

There were cries of ‘shame’ at this insult, forcing Griffith to withdraw it.[44]

Not that it mattered anyway. Their feud was already old news. So was Count Plunkett’s career as leader of the new national movement. Like his Liberty Clubs, his ascendancy would be a short-lived phenomenon, one swiftly forgotten.

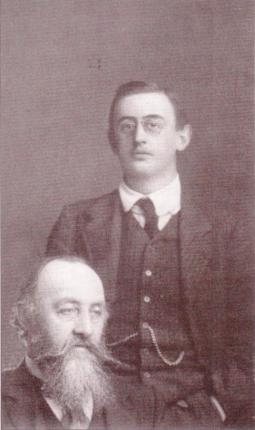

The Plunkett Convention, followed by the Clubs, had marked the peak of his influence. He would remain on the political scene, such as when he led in the very first elected Teachtaí Dálas (TDs) at the opening of Dáil Éireann on the 21st January 1919, while looking “very distinguished” as Geraldine remembered. There, he was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs, and later the Minister for Fine Arts at the second Dáil in August 1921, the latter post being well suited for the distinguished art scholar that was Count Plunkett.[45]

But never again would he enjoy such success as he had had, when his had been the name on the lips of friend and foe alike, and the future looked his to mould and command.

References

[1] Freeman’s Journal, 20/04/1917

[2] Ibid

[3] O’Brien, William. Forth the Banners go: Reminiscences of William O’Brien, as told to Edward MacLysaght (Dublin: The Three Candles Limited, 1969), p. 148

[4] Nugent, Laurence (BMH / WS), pp. 91-2

[5] Plunkett Dillon, Geraldine (edited by O Brolchain, Honor) In the Blood: A Memoir of the Plunkett family, the 1916 Rising, and the War of Independence (Dublin: A. & A. Farmar Ltd, 2006), p. 258

[6] O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770), Part V, p. 133

[7] O’Shiel, p. 32 ; O’Kelly, Seán T. (BMH / WS 1765), Part I, p. 63

[8] O’Brien, Forth the Banners go, p. 148

[9] FJ, 20/04/1917

[10] Dillon Plunkett, p. 258 ; FJ, 20/04/1917 ; New Ireland, 28/04/1917

[11] Dillon, Tommy, ‘Birth of the new Sinn Féin and the Ard Fheis 1917’, Capuchin Annual 1967, p. 394 ; Ceannt, Áine (BMH / WS 264), p. 53 ; Molony, Helena (BMH / WS 391)

[12] Good, Joseph (BMH / WS 388), pp. 30-1

[13] FJ, 20/04/1917

[14] IT, 28/04/1917

[15] Curran, M. (BMH / WS 687), p. 220

[16] De Róiste, Liam (BMH / WS 1698) Part II, p. 168

[17] O’Brien, Forth the Banners go, pp. 112-4

[18] Count Plunkett Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 11,383/6/12

[19] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/13

[20] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/14,16

[21] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/17

[22] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/16

[23] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/10

[24] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/07

[25] Ibid, MS 11, 383/6/8

[26] Ibid, MS 11,383/3/15

[27] Ibid, MS 11,383/11/5

[28] Ibid, MS 11,383/6/26

[29] Cork Examiner, 15/06/1917

[30] Ibid, 06/06/1917

[31] Nugent, pp. 93, 95

[32] O’Brien, pp. 130-133

[33] Plunkett Dillon, p. 260

[34] Ibid ; Irish Times, 11/06/1917, 12/06/1917, 17/11/1917

[35] Irish Times, 19/06/1917

[36] Dillon, p. 395

[37] Police reports from Dublin Castle records (National Library of Ireland), POS 8544

[38] Dillon, pp. 395-6

[39] O’Brien, pp. 136-7

[40] Freeman’s Journal, 26/10/1917

[41] O’Shiel, pp. 85-8 ; O’Brien, p. 102

[42] Molony, pp. 50-1

[43] Dillon, p. 399

[44] Irish Times, 03/03/1922

[45] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 268, 308

Bibliography

Newspapers

Cork Examiner

Freeman’s Journal

Irish Times

New Ireland

Books

O’Brien, William. Forth the Banners go: Reminiscences of William O’Brien, as told to Edward MacLysaght (Dublin: The Three Candles Limited, 1969)

Plunkett Dillon, Geraldine (edited by O Brolchain, Honor) In the Blood: A Memoir of the Plunkett family, the 1916 Rising, and the War of Independence (Dublin: A. & A. Farmar Ltd, 2006)

Bureau of Military Statements

Ceannt, Áine, WS 264

Curran, M., WS 687

De Róiste, Liam, WS 1698

Good, Joseph, WS 388

Molony, Helena, WS 391

Nugent, Laurence, WS 907

O’Kelly, Seán T., WS 1765

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

National Library of Ireland Collections

Count Plunkett Papers

Police Report from Dublin Castle Records

Article

Dillon, Tommy, ‘Birth of the new Sinn Féin and the Ard Fheis 1917’, Capuchin Annual 1967

Count Plunkett had weathered the storm. The identity of the ‘Socialist Party of Ireland’ would never be proven, but it had, perhaps fittingly, done the most harm to the Irish Party. That most people would assume it to be the work of the IPP, out to discredit a vexatious rival, showed how low the stock of the former party of Parnell had sunk.

Count Plunkett had weathered the storm. The identity of the ‘Socialist Party of Ireland’ would never be proven, but it had, perhaps fittingly, done the most harm to the Irish Party. That most people would assume it to be the work of the IPP, out to discredit a vexatious rival, showed how low the stock of the former party of Parnell had sunk. It did not seem like much, that small article on the fourth page in the Freeman’s Journal for the 15th January 1917, tucked away on the top right-hand corner as if the newspaper was faintly embarrassed by it. Under the headline ROYAL DUBLIN SOCIETY – COUNT PLUNKETT’S MEMBERSHIP, the Society announced its call on the member in question to consider his position:

It did not seem like much, that small article on the fourth page in the Freeman’s Journal for the 15th January 1917, tucked away on the top right-hand corner as if the newspaper was faintly embarrassed by it. Under the headline ROYAL DUBLIN SOCIETY – COUNT PLUNKETT’S MEMBERSHIP, the Society announced its call on the member in question to consider his position:

“Doubtless, too,” the Monsignor added wryly, “he was helped by his expulsion from the Royal Dublin Society.” Curran, like O’Brien, clearly did not attribute Plunkett’s victory to his own qualities. Perceptively, Curran also made note of how the issue of an Irish republic, as distinct from straightforward independence, was absent during the election.

“Doubtless, too,” the Monsignor added wryly, “he was helped by his expulsion from the Royal Dublin Society.” Curran, like O’Brien, clearly did not attribute Plunkett’s victory to his own qualities. Perceptively, Curran also made note of how the issue of an Irish republic, as distinct from straightforward independence, was absent during the election.