‘Up the Republic!’

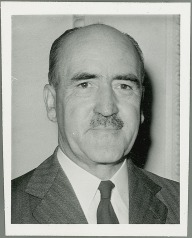

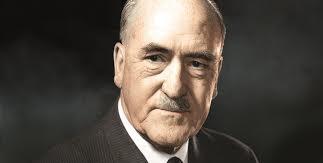

The annual ceilidhe organised in Dundalk by the local Fianna Fáil cumann branch, on the 13th May 1935, was a prominent enough event to merit the attendance of two of the party’s heavyweights: Vivion de Valera, son of the Taoiseach, and the Minister of Defence, Frank Aiken. When the latter prepared to speak, he was interrupted by a group of young men with cries of “Up the Republic!”, “Release the prisoners!”, and others of a distinctly Republican nature.

The Gardaí in attendance moved to eject the hecklers. Aiken, not one to back down from a fight, interceded with the police to “leave the boys alone” and let him have a word with them. With the attention back on him, the Minister addressed the youths and the hall in general.

Fianna Fáil, he said, had been elected by 99.9% of Republicans to lead the national fight and, with the help of God, they would do so. Quite how Aiken had come to that precise percentage was unclear but, in any case, no one in the hall queried him.

The party, Aiken continued, aimed to govern the country with the least possible force but they were nonetheless obliged to protect the public from those who were obstructing the elected government.

‘Up Tom Barry!’

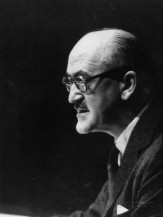

A voice called out: “We must fight!” Aiken replied that every member of the current Cabinet had been fighting for the Republic all their lives. Those now talking about fighting were those who only did so when there was no war on. Unconvinced, the young men resumed their heckling with “Remember the seventy-seven executions!” and “Up Tom Barry!”

If they were trying to impress or intimidate the Minister with a reference to his former comrade in the Irish Republican Army (IRA), then they had misjudged their man. Aiken initially tried to brush off the reminder by saying he did not wish to talk about Barry but, with the slogan being repeated, he had enough, retorting that those who were now shouting must not know anything about their idol. When the IRA was fighting and its members being executed, Aiken continued, Barry had been running around the country, trying to make peace.

With this somewhat cryptic putdown, the tide in the hall turned in the favour of the Minister. Counter-cries of “Up Dev!” were heard, prompting cheers from the audience. Beaten, but with their point already made, the hecklers departed from the hall, where the ceilidhe finally proceeded.[1]

Tom Barry on Trial

It took Barry several weeks to respond. He had, after all, the pressing concern of a trial, accused as he was of breaking into a house in Co. Cork with several others to assault a member of the local Blueshirts, John E. Barry (presumably no relation), and his wife in the November of the previous year.

The only one of the defendants at the hearing who was prepared to act as his own counsel, Barry showed that he had lost none of the pugnaciousness that had marked him out during his days as a guerrilla commander. The testimony of Mr. and Mrs. Barry, the two main witnesses against him, he declared, were contradictory and, in any case, they were the “heads of the Imperialist Party in the district.”

The hearing done, Barry was returned for trial. As he left the court for Cork Jail under police and military escort, he was cheered by a waiting crowd and then again as he was recognised passing through the area. It had been over a decade since the War of Independence but his renown as one of its most successful IRA leaders remained undimmed.[2]

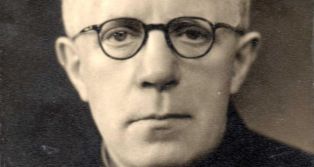

In the meantime, Father Thomas F. Duggan had intervened on Barry’s behalf. He had been closely acquainted with Barry, having attended his wedding, along with Michael Collins and Éamon de Valera in friendlier times. His letter to the newspapers was more in sorry than in anger. It had been unnecessary for Aiken to stir up past controversies, Duggan wrote, particularly in regard to a man of such soldierly achievement, whatever one happened to think of his present course of action (an indication that Duggan did not think too much of it).[3]

‘Of the Meanest Kind’

When Barry did find the time to write to the papers – three of which, Irish Press, Irish Independent and Cork Examiner, would publish the correspondence of the unfolding feud – it was in a very different tone to Duggan’s. Barry denounced the “vicious and lying attack on me….This statement of Mr. Aiken is of the meanest kind, as he merely suggests to the audience, without definitely stating so, that I was guilty of some dishonourable conduct.”

It was the vagueness of Aiken’s public statements that particularly infuriated Barry. Going where Aiken had not, Barry proceeded to put meat on the bones of the accusations he believed the other man had alluded to:

- That he had not fought in the Civil War.

- That he had been running about the country attempting to make peace instead of aiding his comrades while they were facing death in battle or by execution.

- That his conduct during the Civil War had, in general, been dishonourable and cowardly.

Having set up the points against himself, Barry went on to tick them off:

- He would leave the question as to whether or not he had fought in the Civil War to those Volunteers who had accompanied him on active service.

- At no point had he attempted to make peace.

Barry did not deign to address his own third point, presumably leaving his record to speak for itself. As for the second, he conceded that he had been involved in a couple of attempts but only in passing: the ‘Archbishop Harty Proposals’ and the ‘Cease Fire and Dump Arms Policy’.

The first effort had involved Father Duggan – the same man who would come to Barry’s defence – acting as a courier in February 1923 with copies of proposals addressed to individual members of the IRA Executive, including Barry. These proposals were unanimously rejected.

In March, Duggan again forwarded proposals, this time backed by Archbishop Harty of Cashel. Barry agreed to circulate them among the Executive and, once more, the proposals were uniformly turned down. As for the second peace effort, the ‘Cease Fire and Dump Arms Policy’ of May 1923 had been unanimously adopted by the IRA Executive, including both Barry and Aiken.

At no point had Barry acted with any other motive than the saving of Republican lives in the face of the Free State’s overwhelming superiority. Laying the onus on Aiken to explain his remarks in Dundalk or else publicly withdraw them, Barry ended his letter with some pointed innuendo of his own:

Mr Aiken’s attack now – 12 years afterwards – does not arise out of the Civil War period, but out of present day circumstances.[4]

‘His New Campaign of Vilification’

Irish Press readers were not given the last sentence of Barry’s letter, which was left in by the Irish Independent and Cork Examiner:

And I tell Mr Aiken that his new campaign of vilification against Republicans will fail to stop the Republican advance just as surely as his coercion campaign has already failed.[5]

There was a reason for the Irish Press editors to be so coy. After all, Fianna Fáil, whose party line the Irish Press was there to follow, was conscious of its own Republican heritage. An article on the 4th June stressed the contribution of ‘Old’ IRA men – those who had been members during the revolutionary years but not necessarily afterwards – to the campaign of the Fianna Fáil candidate in a Galway by-election (by contrast, the Opposition-leaning Cork Examiner focused more on the voter apathy during the same election).[6]

Accusations of turning on one’s own were perhaps best left unread.

Nonetheless, Aiken felt obliged to respond to Barry’s letter with one of his own. His tone was one of embarrassment, perhaps by the unseemliness of the whole affair, but he was also unapologetic. He pointed out that he had had no intention of mentioning Barry in Dundalk, and that only after provocation had Barry’s name been drawn from him. But after all that, what Aiken had said was true and he would not be taking it back.

As for Barry’s insistence that he had sought to make peace during the Civil War, Aiken retorted that the former’s activities had not been quite as innocent as he was making out. Indeed, Barry’s extracurricular activities had been a source of great concern to the then IRA Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch.

‘Doing His Worst’

A letter of Lynch’s from the 19th February 1923 was quoted: “I have already done my utmost to keep you informed of peace moves here. You have also facts in the Press re Father Duggan. Barry is doing about his worst here.” Barry had apparently done his ‘worst’ earlier in the month, having made a personal offer through the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Free State Cork Command, according to Aiken.

Barry maintained his independent streak to the end of the Civil War. While he assented to the ‘Cease Fire and Dump Arms Policy’, he remained dissatisfied due to the arms in question not being put beyond use. On the 8th June, Barry wrote a memorandum urging the liquidation of the weapons, and followed that up on the 20th with a threat to restart the Civil War if the arms remained usable.

Unintentionally confirming Barry’s argument that Aiken’s attacks emanated from contemporary circumstances as much as past ones, Aiken pointed to the inconsistency of Barry now urging a course of action that could only lead to another civil war. While some might find this incomprehensible, those “who know Mr. Barry’s irresponsibility, however, are not surprised”:

Courage is not the only quality needed in a solder. A sense of discipline is also necessary, but Mr. Barry does not appreciate the fact.[7]

It was because of this indiscipline, according to Aiken, that he forced Barry to resign from the IRA Executive on the 11th July. Aiken archly posed a question to the same young hecklers in Dundalk: if they regarded Barry as a responsible leader, why did he postpone the resumption of military activities – an oblique reference to Barry’s re-entry to the IRA in 1932 – until Fianna Fáil went into government?[8]

Peace-ish Talks

Aiken sounded more aggrieved at any Republican violence happening on his party’s watch than with the violence per se. He was on firmer ground when talking about Lynch’s displeasure with Barry’s attempts at peace. The two had fallen out over the issue and badly so but Lynch had initially been open to the idea of a peaceful solution.

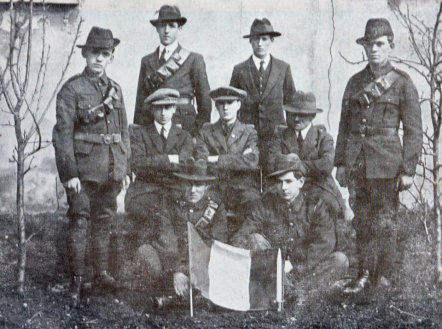

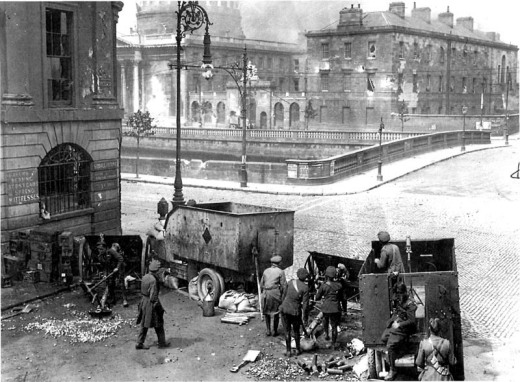

Sometime in mid-1922, Barry and Liam Deasy, a fellow Corkonian and the anti-Treatyite O/C of the First Southern Division, had met two officers in the Free State Army to iron out a possible peace proposal. Among the suggestions was that both sides would disband and be reformed under a fresh executive that would ensure the Government would reject the undesirable elements in the Treaty.

The men involved were sufficiently enthused about their proposal to consider taking it directly to General Richard Mulcahy. The results of the parley were included in the minutes of an IRA Executive meeting on the 16th-17th October 1920, showing that not only was Lynch aware of these peace efforts but that he made no move to stop them. The arrogance of the IRA Executive shined through in their presumption that any peace deals would be made largely on its terms, with compromises to be made primarily by the opposition, but the topic of peace had not yet become a poisonous one. [9]

By the start of 1923, it had.

Barry continued to pursue the possibility of peace through the efforts of Father Duggan. Well-liked and trusted by both sides, Duggan had been working ceaselessly to find a way to end the Civil War since its start. Intransigent in his belief that victory was still possible, Liam Lynch made it clear to Duggan that he was not about to compromise in the slightest.

To make sure Barry also understood, Lynch wrote him a “strongly worded letter,” in the words of the latter’s young aide Todd Andrews, ordering his subordinate to break off any further peace efforts.[10]

Pax Barry

Lynch perhaps assumed that that would be the end of it, until he and Andrews were abruptly awoken one night by someone kicking in their bedroom door. Holding a candle in one hand and waving a sheet of paper in the other, Barry demanded of Lynch whether he had written the letter.

When Lynch calmly affirmed, Barry ranted that he had fought more in a week than the Chief of Staff had done in his life. Andrews could not help but laugh after Barry had stormed off: “Barry’s dramatic entrance holding the candlestick with the lighted candle struck me as having something of a character of an Abbey Theatre farce.”[11]

To Father Duggan, Barry’s impeachable record as a guerrilla fighter had allowed him to say what others did not dare. Those same credentials, however, had also gone to his head.[12]

Lynch had stoically waited out Barry’s tirade but relations between the two had deteriorated past the point of repair. If Lynch was an inflexible militant, then Barry had become a militant peacenik, one willing to use whatever tool at his disposal to end the fratricidal conflict.

In May 1923, Barry tried the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). With the help of a go-between, he proposed unsuccessfully to Seán Ó Muirthile, a senior figure in both the IRB and the Free State Army, for the secret society to exert its influence in reuniting the two warring sides. As Barry made the offer in his own name, it is unlikely that Lynch or anyone else had authorised or even knew of it.[13]

Venom

The subsequent meeting between Barry and his commanding officer fared no better. Lynch had arranged to rendezvous with him and the equally tenacious Father Duggan in Ballingeary, Co. Cork. Although the date is uncertain, it occurred shortly after the Ballyseedy Massacre of the 6th March 1923.

Lynch and Andrews arrived in Ballingeary to find the other two already present and waiting with a group of several others on the opposite side of the street. To Andrews, the surreal scene resembled one from a Western film where rival posses would ride into town for a shootout.[14]

While no six-shooters were drawn, the talks ended as fruitlessly as before. Frustration turned to loathing; according to historian Meda Ryan in her 1982 book on Barry (not repeated in her 2003 edition), his friends “would say that Barry had venom in his voice when speaking” of Lynch.[15]

It is perhaps unsurprising then that it was Barry who proposed Aiken as the new Chief of Staff after Lynch’s death. Anyone would have to be more amenable than his predecessor. Barry would soon learn how wrong he was.[16]

Meet the New Boss…

On the 11th July 1923, Barry stepped down from the IRA Executive. In his resignation letter, he insisted that any suggestion of his had made had been entirely dependent on the majority of the leadership agreeing to it. Furthermore:

I also want to state that the rumours propagated in some cases by Republicans as to my negotiations for peace with the Free State, are absolutely false. Lies, suspicion and distrust are broadcasted, and I have no option but to remove myself from a position wherein I can be suspected of compromising the position. I have never entered into negotiations for peace by compromise with the Free State.[17]

Barry admitted to a technical breach of discipline in the sending of a signed communication with three other senior IRA men. In this, he had been motivated by a desire to save the lives of their men and did not regret anything. Despite the ignominious circumstances of his exit, he affirmed his willingness to take up arms again for an independent Ireland when called upon.[18]

Tension had been hinted at in the minutes of earlier Executive meetings, although not, on the surface at least, irreconcilably so. Aiken was elected the Chief of Staff on the 26th April 1923 after being put forward by Barry and seconded by Seán MacSwiney. A resolution, proposed by Aiken and again seconded by MacSwiney, empowered the Executive to make peace with the Free State on the basis of certain conditions.

That they felt the need to include quotation marks around the word ‘Government’ in regards to the Free State indicates that the twelve men present were finding even this mild climb-down a bitter pill to swallow.

It was at least a break with the late Lynch’s intractability but not enough of one for Barry. He proposed an amendment, seconded by Tom Crofts, that all armed resistance to the Free State be called off. With only Barry and Crofts voting for the amendment, one abstaining and the other nine against, the motion was defeated.

The vote for another motion – the recommendation to carry on fighting should the Free State reject peace overtures – was more evenly divided, with six for, including Aiken, and six against, including Barry and Crofts. Once again Barry had found himself to be the ‘moderate’ opposition against a hardliner Chief of Staff.[19]

‘Statement Prejudicial’

Barry was not one to do nothing when something was an option, and took the time until the next meeting on the 11th July to try and break the deadlock. However well-intentioned, he had finally gone too far.

When the Executive met again, Aiken read out a document he had received that had been signed by Barry and three other senior officers, two of whom – Crofts and Liam Pilkington – were present. The signatories had threatened in their circular to take unauthorised action. Though the nature of this threat was not included in the minutes, it was probably to restart the fighting if the IRA arms were not decommissioned.

With Barry running late, it was agreed to postpone further debate until he arrived. When he did, Aiken repeated what he had said before. The document contained a threat, Aiken said, and must be withdrawn. Cowed, Crofts and Pilkington agreed and withdrew their offending statement.

Barry was not so easily daunted. Aiken pressed him to withdraw as the others had done or else he would request his resignation. When Barry chose the second option, Aiken, perhaps taken aback, asked him to reconsider. Having decided he had already made his bed, Barry stuck to his decision and left the meeting. Seeing which way the wind was turning, Pilkington proposed that his former ally’s resignation be accepted. And so it was.[20]

Although he had made some effort to keep Barry on board, Aiken found the whole episode so distasteful that, in a letter on the 19th July 1923, he threatened the suspension and court-martial of anyone who attempted to “seduce Volunteers from their allegiance, or by doing any act or making any statement prejudicial to the maintenance of discipline.”[21]

Tom Barry’s Second Reply

Barry opened his follow-up letter on the 7th June 1935 with a complaint that the respective newspapers involved had not published his previous one in full. Due to the considerable publicity the matter had received, Barry asked that this message be published unabridged.

He did, after all, have a lot to say.

The only satisfactory way Barry could see of resolving the controversy would be the setting up of a committee of enquiry. This panel would investigate all the allegations, receive any evidence and then publish their findings. Barry did not think it would be hard to find three or five impartial men to serve on this proposed committee.[22]

For Barry, there could be no purer or more reliable methodology than that of a committee. When approached by the Bureau of Military History (BMH) in 1958, Barry not only refused to give a statement – anything of importance he had already said in his memoir – but questioned the BMH’s practice of receiving any and all statements without prior verification. Better instead, in his opinion, for a committee to go through every submitted statement and reject accordingly for absolute historical accuracy.[23]

‘From a Republican Point of View’

Obviously deciding that the best way of fighting fire was to pour on the gasoline and strike a match of his own, Barry drew up a list of his accusations against Aiken for the latter’s Civil War conduct:

- Aiken, despite his professions of being opposed to the Treaty, joined the Free State Army in 1922.

- He remained in the Army even when the Four Courts were attacked, after which he came to Dublin to draw his pay as a Free State officer before returning to Dundalk.

- He became neutral on his return to Dundalk, only throwing his lot in with the Anti-Treaty side after his arrest by the Free State and subsequent escape.

- Aiken avoided all fighting, except in Dundalk on one occasion.

- That he came unarmed to the IRA Executive meetings demoralised those who expected such a leader to be armed.

- Aiken was mainly responsible for the defeat in the Civil War due to his initial alliance with the Free State, his wobbling attitudes and his refusal to fight.

After these six points – which were actually five since the sixth was just a summary of the previous ones – Barry went on to discuss his ‘Leinster House Proposal’. He had made a passing reference to it in his previous letter with no details other than a claim that it could have turned defeat into victory.

Lest this ‘Leinster House Proposal’ be misconstrued as political in nature (clearly a dirty word in Barry’s dictionary), he explained that after the ‘Cease Fire and Dump Arms’ orders, he proposed leading a commando squad into Leinster House to catch the Free State Government inside.

Both Aiken and De Valera queried the feasibility of such a daring plan, with the former ultimately nixing what could have brought the War, in Barry’s view, to a “successful conclusion from a Republican point of view.”[24]

‘Coercion Campaign’

Aiken had lambasted the other man for the hypocrisy of urging peace before and a militant view now. Paying evil unto evil, Barry pointed out that he, unlike Aiken, had not issued orders during the Civil War forbidding IRA members to recognise Free State institutes and courts, and then, once in government, jailing Republicans for refusing to acknowledge these same institutions.[25]

Barry was not the only one with the belief that Fianna Fáil was giving its fellow ideological travellers a raw deal. In Co. Kerry, Listowel Urban Council passed a motion protesting against the suppression of An Phoblacht newspaper and the closing of Republican offices. Members of the Council called on the Taoiseach to end the coercion of the IRA since it had put him into office in the first place, something which the electorate might have been surprised to hear.

But the Council was not speaking idly on its other points. In Longford, Gardaí seized the latest issue of An Phoblacht as it was being printed. All copies were taken away, with detectives remaining on the premises. In Dublin, women from Cumann na mBan marched through Dublin to protest against the forced closure of their offices.[26]

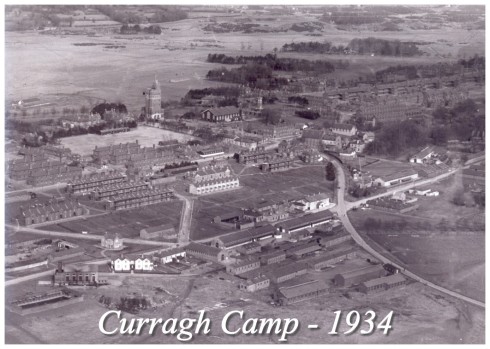

Even the victor of Kilmichael was not untouchable. Accompanied by his wife and large numbers of friends, Barry left Cork for the Curragh Camp. For the past fortnight he had been out on parole but with that ended, he was to complete a sentence of six months, courtesy of the Military Tribunal, for seditious utterance and unlawful associations.[27]

Frank Aiken’s Second Reply

Aiken dug in his heels in his subsequent letter to Barry a day later, the rapidity of each other’s replies revealing in itself how heated the exchange was. Aiken reiterated his accusations in a list of his own:

- Barry had carried out unauthorised peace negotiations with the Free State in the spring of 1923.

- Liam Lynch had been deeply worried about these activities.

- Barry had urged the destruction of weapons at the end of the Civil War.

- His resignation had been forced by Aiken due to insubordination.

These facts were true and beyond a shadow of doubt, according to Aiken. Indeed, Barry had not really tried to deny them. Aiken added that he would have no further dealings with his former comrade. After all, if those in Fianna Fáil replied to every false accusation thrown their way, they would never get anything done. It was only to prevent impressionable youths from being misled that Aiken continued to respond.

Nonetheless, it is clear that Barry had wounded him on a personal level as he denied that Barry had ever suggested anything like an attack on the Free State Government:

Even if Mr. Barry, to cover his confusion, were to prove that the I.R.A., after Liam Lynch was killed, had elected as their Chief of Staff the greatest coward in the world, and even if it were true (and it is not) that he proposed a stunt attack in Dublin in May, 1923, after hostilities had ceased…[28]

Aiken continued to goad at the inconsistency of Barry’s attitude at the end of the Civil War, in particular his adamance that the IRA arms be destroyed, with his more militant one in the present which only restarted when Fianna Fáil entered government.

Frank Aiken’s War

The rest of his letter was an explanation of actions during the Civil War prior to joining the anti-Treaty side, as well as a defence against Barry’s accusations. The only point of Barry’s he ignored was the one about demoralising the IRA Executive by turning up unarmed to meetings but that was a nonsensical one anyway.

Aiken explained that he had never made any secret of his horror at the thought of civil war and had done his best to prevent it. To head off the impending crisis, he had brought together Arthur Griffith, Éamon de Valera, Michael Collins, Lynch and others on both sides of the growing divide. From this meeting came the Collins-de Valera Pact of May 1922. While short-lived, the Pact had at least brought an end to the sporadic violence from before.

When the Four Courts were attacked in June 1922, Aiken made his way to Dublin and urged General Richard Mulcahy to call a truce. When that failed, Aiken travelled to Limerick in the hope of contacting Liam Lynch, the implication being he had been an Anti-Treatyite earlier than he had officially declared.

‘Wise, Loyal and Disciplined’

Having failed again, he returned to Dundalk where he was imprisoned by the Free State. Following his escape, “calculating and seeing clearly the cost, I deliberately took the decision to fight my best to resist the overthrow of the Republic by a coup d’etát,” by which he described the formation of the Free State.

Barry had tried to paint the other man as mercenary and insincere. Aiken had responded with a self-image of a man true to his principles even when sorely tested by circumstances beyond his control.

In case anyone continued to doubt his Republican credentials, Aiken told of how he had done his best to abolish the hated Oath of Allegiance since entering government. Having adopted the political path, Aiken remained determined to “oppose internecine strife and to do my utmost to unite all wise, loyal and disciplined citizens to secure a Republic.”[29]

‘Wise’, ‘loyal’ and ‘disciplined’ – these three adjectives were clearly synonymous in Aiken’s worldview, with the last in particular a favoured watchword.

An earlier letter to the press in 1933 allowed Aiken to expound on the dual subjects of discipline and the young. Sounding as much as a moral reformer as a politician on a soapbox, Aiken wrote of how: “The success of this generation in the achievement of national freedom…will be governed in no small measure by the extent to which the principle of national discipline is accepted…by the young men of to-day.”[30]

Letters of Aid

Barry’s return to jail seemed to have given him pause, for he did not reply at once. In the meantime, four of his comrades from the past stepped in and lent a helping hand. Three of them – James Donovan, Seán Goughlan and Seán MacSwiney – put their names to a letter on the 12th June, saying that Barry had been attached to their 1st Cork Brigade in the IRA since his return from abroad in 1927, as part of which he had carried out all his assigned duties (however, historian Brian Hanley says that Barry did not rejoin the IRA until 1932).[31]

This letter was in refutation to Aiken’s claim that Barry had not resumed his IRA activities until the advent of the Fianna Fáil Government in 1932. Considering how Barry was imprisoned partly as a result of these activities, it probably was not the most helpful of letters, however well meant.

Another Cork IRA member, Tom Crofts, wrote a second letter to the newspapers on the same day in regards to the controversy. As he had often been the only other member of the IRA Executive during the Civil War to side with Barry, it was only fitting that he should come in as support now.

Introducing himself as the O/C of the 1st Southern Division and a member of the IRA Executive during the Civil War, and thus in a position to know, Crofts addressed the claim by Aiken that Barry had made a personal peace offer on the 19th February 1923 to the GOC of the Free State Cork Command. That offer had actually been made by Father Duggan, who assured Crofts that he had not been authorised by Barry or any other IRA officer to act on their behalf.[32]

Charles F. Russell

Letters to the press seemed solidly behind Barry. The only dissenting pen was from a retired colonel in the Free State Army, Charles F. Russell. In response to Barry’s claim that he had never entered into negotiations with the enemy, Russell told of how he had met Barry and Liam Deasy in Cork for the purposes of a peace conference. The only detail Russell gives is that it was held in Father Duggan’s house but says nothing about what was discussed. Afterwards, Russell drove the two Anti-Treatyites past the Free State sentries.[33]

Russell dated the parley to 1923 but, as historian Meda Ryan points out, Deasy had been in jail since January, making his presence an implausible one.[34] Nonetheless, the meeting is mentioned in the minutes of the IRA Executive for October 1922, the same one in which Barry and Deasy had discussed with their counterparts the possibility of both armies disbanding and coming together in a fresh start.

Russell added that he had made a full report to GHQ afterwards, though it is doubtful that he included everything. The civilian Government, after all, would have been firmly under the thumb of the military under these new arrangements. The men at the meeting had been sufficiently enthused about their proposal to consider taking it directly to General Richard Mulcahy in Dublin but, failing that, they would appeal directly to officers in the Free State Army to defect.[35]

Russell emphasised in his letter how he had been acting under orders (however unlikely Mulcahy would have approved of all that was said). The same could be said of Barry. After all, Lynch had known of these negotiations and permitted them. But in the years afterwards, that was not what people wanted to hear. There was room only for black and white, for heroes of incorruptible purity or vile traitors, and none for the shades of grey.

Tom Barry’s Third Reply

Imprisonment may have slowed Barry but it had not stopped him. His second letter, dated the 13th June, began by noting Aiken’s refusal of the offer of an impartial committee to mediate on the matter. Which was not entirely correct. Aiken had not so much refused the offer as refused to acknowledge it. As for Aiken’s dismissal of any further dealings with Barry, Barry assured his readers that Aiken “will have further dealings with me or else withdraw his charges.”

For those readers failing to keep track, Barry reiterated the said charges: that he had made a personal offer of peace through the GOC of the Free State Cork Command on the 19th February 1923. As part of this, Aiken had quoted a dispatch, also dated the 19th February 1923, from Liam Lynch about Barry’s and Father Duggan’s activities appearing in the press.

Sounding very different to the man who had screamed at his superior about the deficiencies in the other’s fighting record, Barry denounced the use of Lynch’s “honoured name” as a new low. It was also factually wrong. According to Barry, the late general could not have written such a thing on the 19th as Father Duggan’s name had not appeared in the media in regards to the ‘Archbishop Harty proposals’ until the 9th of March.

As for the personal peace offer to the GOC, Barry flatly repudiated such a thing. Showing his willingness to press a point, Barry challenged Aiken to request Colonel David Reynolds, the GOC in Cork at the time, to state whether or not he had ever received such a proposal through him.

As to what Aiken had said about Barry’s disciplinarian problems, Barry fell back on his earlier stance; that by March 1923, the Anti-Treatyites had been militarily defeated. Barry had thus focused on saving as many Republican lives as he could, and he would do the same today if under similar circumstances.

‘Very, Very Serious Charges’

Disappointingly, Barry did not raise again the subject of his ‘Leinster House’ proposal which Aiken had denied ever being put forward. Indeed, Barry’s defence of his lack of martial spirit on pragmatic and humanitarian grounds is sharply at odds with his claim that he offered to decapitate the enemy government in a last throw-of-the-dice blitz.

Also lacking was the same zeal to attack Aiken’s Civil War conduct as before, saying merely that he had “made very, very serious charges against Mr. Aiken…which he has not denied.” Aiken had more defended than denied Barry’s charges but that distinction seemed lost on the other man.

Aiken, he continued, had “evaded and confused the issue” – something that could be said of both men. Barry wrapped up his third letter by once again challenging Aiken to either prove his charges or publicly withdraw them.[36]

Conclusion

Aiken was true to his word in refusing to have any further dealings with Barry. He sent no further replies and the debate petered out, leaving Barry with the satisfaction at least of having the last word.

Later, on the 21st June, Barry could claim another victory: he and the other four defendants were acquitted of the charges of assault against John E. Barry and his wife in a courtroom that had attracted so many onlookers that many could not be admitted for lack of space. It was a small respite as Barry was led away back to Cork Gaol and then returned to the Curragh Camp to finish the sentence imposed by the Military Tribunal.[37]

This had not been the first time Aiken had had to publicly defend his past record in a testy exchange of letters with former comrades. Two years ago in 1933, it had been him against Seán MacBride, the point of contention being his conduct during the IRA Convention of 1925 when, as Chief of Staff, he had opposed the Republican policy of abstentionism.

MacBride had mocked Aiken’s attempts to show his conduct as “logical and consistent…to reconcile his past with his present acts,” not something Aiken would have disagreed with, minus the sneer.[38] For him, his actions had been logical and consistent. But then, Barry could have argued the same. Both had done what they thought had been right at the time.

Barry was a loose cannon and Aiken a turncoat as far as the other man was concerned but, in their determination and willingness to bend, if not defy, the accepted norms of their contemporaries, the two had more in common than they cared to acknowledge. Perhaps they were simply too similar to be anything other than adversaries.

Both had been flexible enough to challenge the rigidity of their peers and to see alternative options to fruitless conflict: for Barry, the need for compromise regardless of what his superiors thought, and with Aiken, the possibility that politics might achieve what brute strength could not. But, however much they were capable of defying Republican orthodoxy, both men were believers enough to be embarrassed when others pointed out their heresies.

Historian Matthew Lewis describes the Aiken-Barry exchange as a “brief, if uneventful, public spat.”[39] More perceptively, Evan Bryce notes how the “republican ‘big men’ were still scrapping over ownership of the glorious past.”[40] But the dispute had been less about the glory and more about the ignominy, and the past not so much a treasured prize as an unclean scab that some could not help but pick at.

References

[1] Irish Independent 14/05/1935

[2] Irish Press, 09/05/1935

[3] Ibid, 15/05/1935 ; Parsons, Michael (27/06/2015) ‘Cork priest who served in two World Wars but was staunch nationalist’, The Irish Times (Last accessed on 06/04/2016)

[4] Irish Press, 03/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 04/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 03/06/1935

[5] Irish Independent, 04/06/1935

[6] Irish Press, 04/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 03/06/1935, 15/06/1935

[7] Irish Press, 06/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 06/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 06/06/1935

[8] Ibid

[9] Ernie O’Malley Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 10,973/15/4

[10] Andrews, Todd. Dublin Made Me (Dublin and Cork: Mercier Press, 1979), p. 279

[11] Ibid, p. 280

[12] Irish Press, 15/05/1935

[13] Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin, P7a/209

[14] Andrews, pp. 280-1

[15] Ryan, Meda. The Tom Barry Story (Dublin and Cork: Mercier Press, 1982), p. 124

[16] Frank Aiken Papers, University College Dublin, P104/1263

[17] Ernie O’Malley Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 10,973/15/20

[18] Ibid

[19] Frank Aiken Papers, University College Dublin, P104/1263

[20] Ibid, P104/1264

[21] Ernie O’Malley Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 10,973/15/21

[22] Irish Press, 07/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 07/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 07/06/1935

[23] Barry, Tom (BHM / WS 1743), p. 3

[24] Irish Press, 07/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 07/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 07/06/1935

[25] Ibid

[26] Irish Press, 06/06/1935, 07/06/1935

[27] Irish Press, 06/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 07/06/1935 ; Ryan, Meda. Tom Barry: IRA Freedom Fighter (Douglas Village, Co. Cork: Mercier Press, 2005), p. 288

[28] Irish Press, 08/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 08/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 08/06/1935

[29] Ibid

[30] Irish Press, 29/11/1933

[31] Hanley, Brian. The IRA: 1926-1936 (Dublin: The Four Courts, 2002), p. 191

[32] Irish Press, 12/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 12/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 12/06/1935

[33] Irish Independent, 17/06/1935

[34] Ryan (2005), p. 457

[35] Ernie O’Malley Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 10,973/15/4

[36] Irish Press, 15/06/1935 ; Irish Independent, 14/06/1935 ; Cork Examiner, 14/06/1935

[37] Cork Examiner, 22/06/1935

[38] Irish Press, 16,22,23,29/11/1933

[39] Lewis, Matthew. Frank Aiken’s War: The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923 (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2014), p. 196

[40] Evans, Bryce. ‘Frank Aiken: Nationalist’, Frank Aiken: Nationalist and Internationalist (eds. Evans, Bryce and Kelly, Stephen) (Sallins, Co. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, 2014), p. 12

Bibliography

Newspapers

Cork Examiner

Irish Independent

Irish Press

Bureau of Military History / Witness Statement

Barry, Tom, WS 1743

Books

Andrews, Todd. Dublin Made Me (Dublin and Cork: Mercier Press, 1979)

Evans, Bryce and Kelly, Stephen (eds.). Frank Aiken: Nationalist and Internationalist (Sallins, Co. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, 2014)

Hanley, Brian. The IRA: 1926-1936 (Dublin: The Four Courts, 2002)

Lewis, Matthew. Frank Aiken’s War: The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923 (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2014)

Ryan, Meda. Tom Barry: IRA Freedom Fighter (Douglas Village, Co. Cork: Mercier Press, 2005)

Ryan, Meda. The Tom Barry Story (Dublin and Cork: Mercier Press, 1982)

Online Article

Parsons, Michael (27/06/2015) ‘Cork priest who served in two World Wars but was staunch nationalist’, The Irish Times (Last accessed on 06/04/2016)

Document Collections

Ernie O’Malley Papers, National Library of Ireland

Frank Aiken Papers, University College Dublin

Richard Mulcahy Papers, University College Dublin