Doubtful Mercy

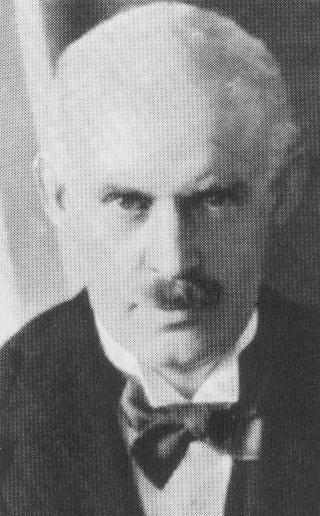

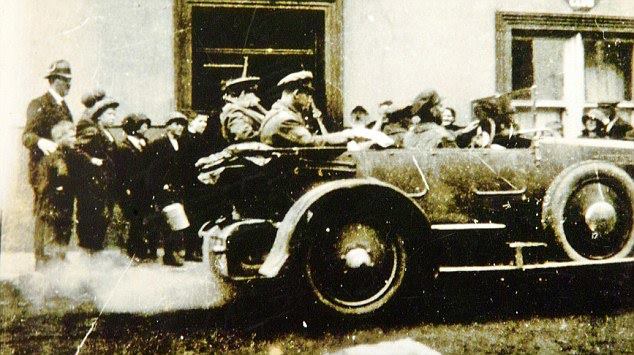

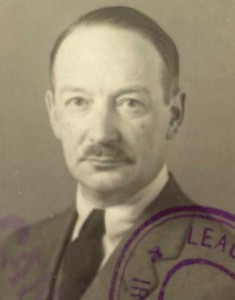

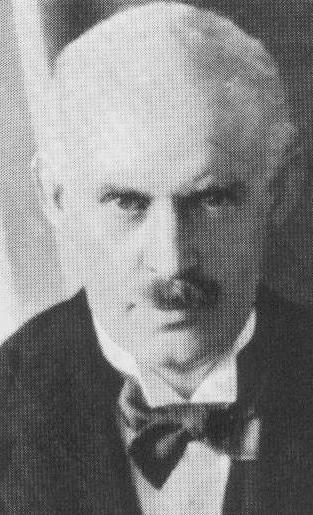

Life in Ireland turned a little more perilous on the 19th December 1919, courtesy of a hail of bullets and bombs cast at the convoy of three cars approaching the Ashtown Gate of Phoenix Park, Dublin. On board the first was Lord French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who was returning from a brief visit to the West and had arrived at Ashtown Station on the morning train. From there, the trio of cars picked him up, providing an armed police and military escort back to the Viceregal Lodge in a journey that normally would have taken no more than five uneventful minutes.

The engagement was a brief one – “those who heard it are agreed that its duration would be about one minute,” reported the Irish Times – but fierce all the same. Detective Sergeant Hally, seated next to the chauffeur of the first vehicle, was struck in the hand, either by a bullet or bomb fragments, mangling his thumb and two fingers. The man at the wheel kept his nerve, however, and sped forward, passing out of range of their assailants. That the car received minimal damage – one hole to the rear and another through the driver’s window – attested to the wisdom of the decision not to stop and fight it out.

The second car, in contrast, was badly mauled, losing all its windows and taking over a dozen bullet shots to its body. Had there been anyone other than its driver inside, they would almost certainly have been similarly battered; as it was, the sole occupant escaped injury.[1]

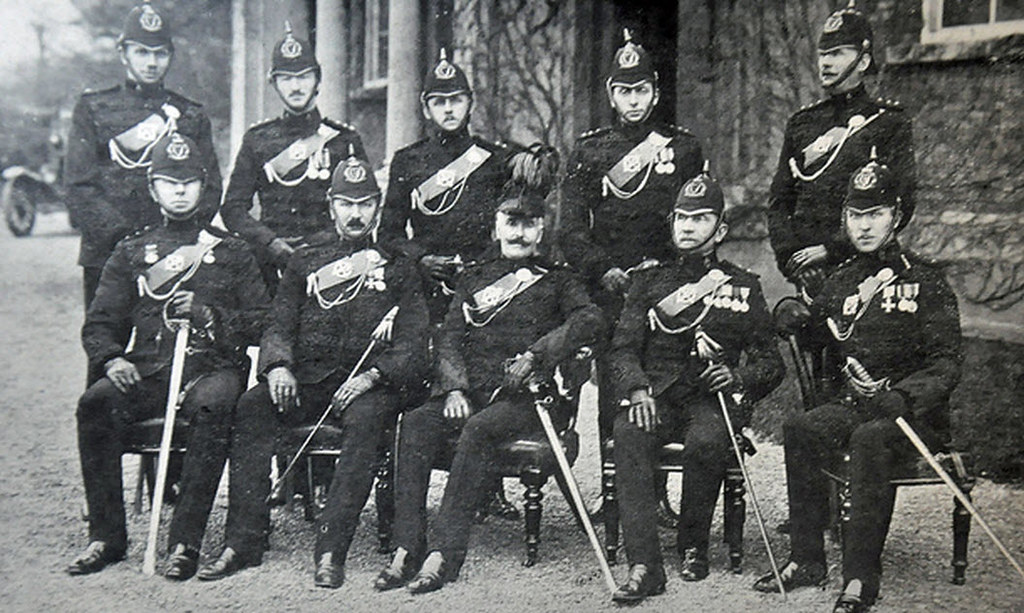

It was the third car that turned the tide when it caught up with the scene: open-topped, with six soldiers who opened fire at once, killing one of the assailants. Sergeant George Rumble later testified at the inquiry into the deceased about how he had pulled his firearm out at three of the ambushers who were behind a two-wheeled cart by the road.

Coroner: You aimed at one man?

Rumble: Yes, he was aiming at me with a revolver.

Coroner: What was the result?

Rumble: My shot made the gravel on the road at the man’s feet to fly around him. At the same time, he jumped and made out of sight. The other man (the second) was in the act of pulling the pin out of a bomb with his left hand, he having the bomb in his right.

Coroner: What did you do?

Rumble: I fired at him.

Coroner: What was the result?

Rumble: The man put up his arms and fell straight on his back.

Coroner: During this time, were there bullets flying around?

Rumble: Yes.

Coroner: Did one bullet pass close to your face?

Rumble: Yes, it burned my lip and smashed the windscreen.[2]

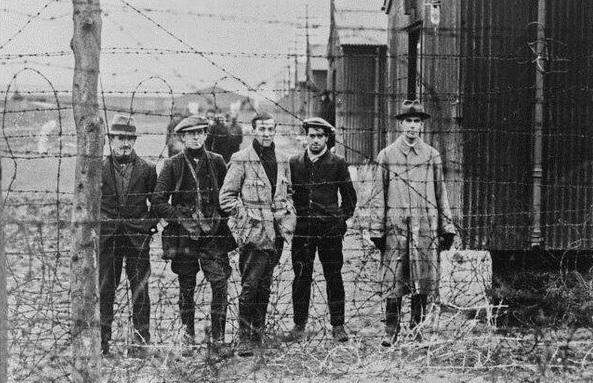

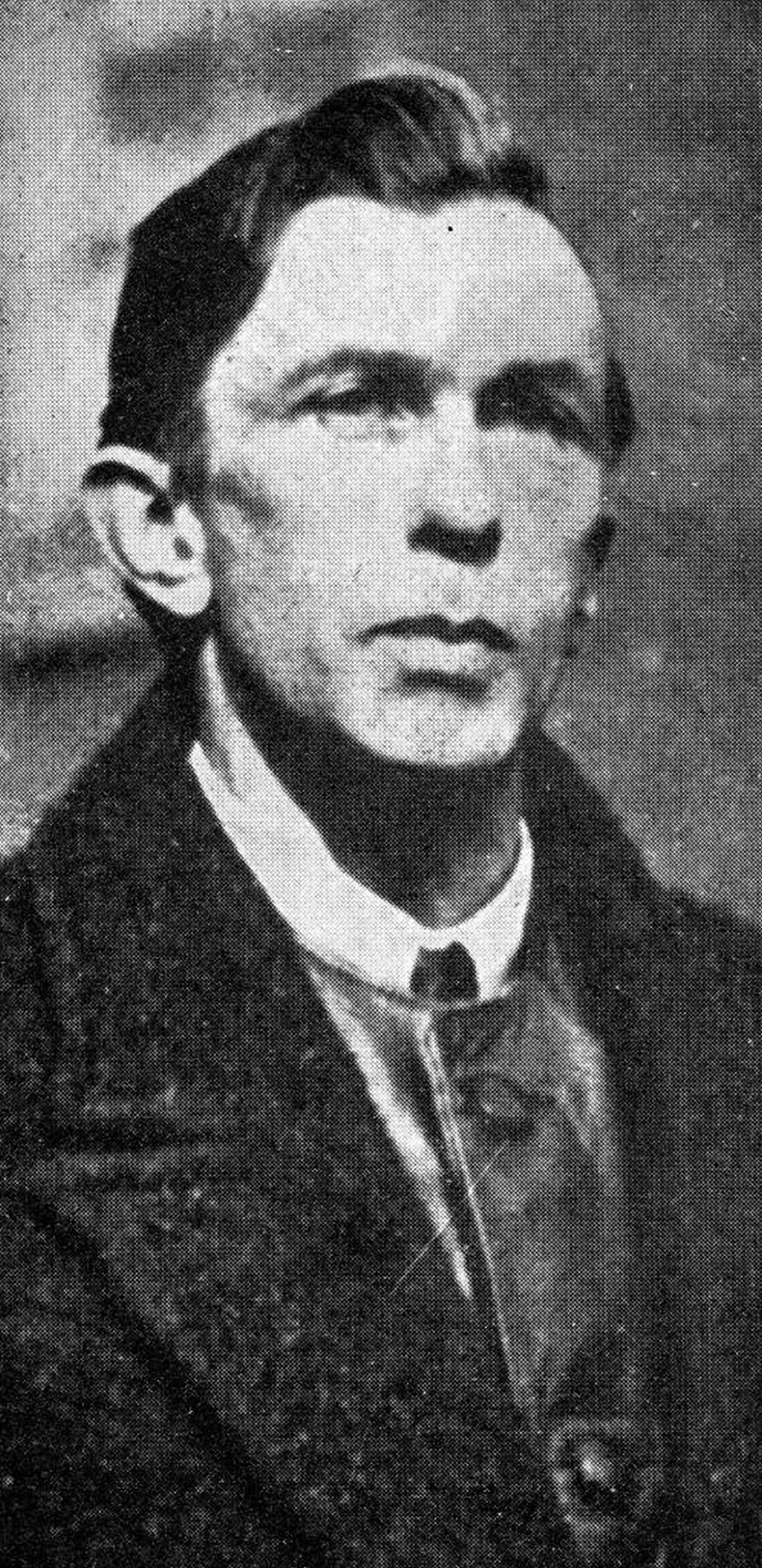

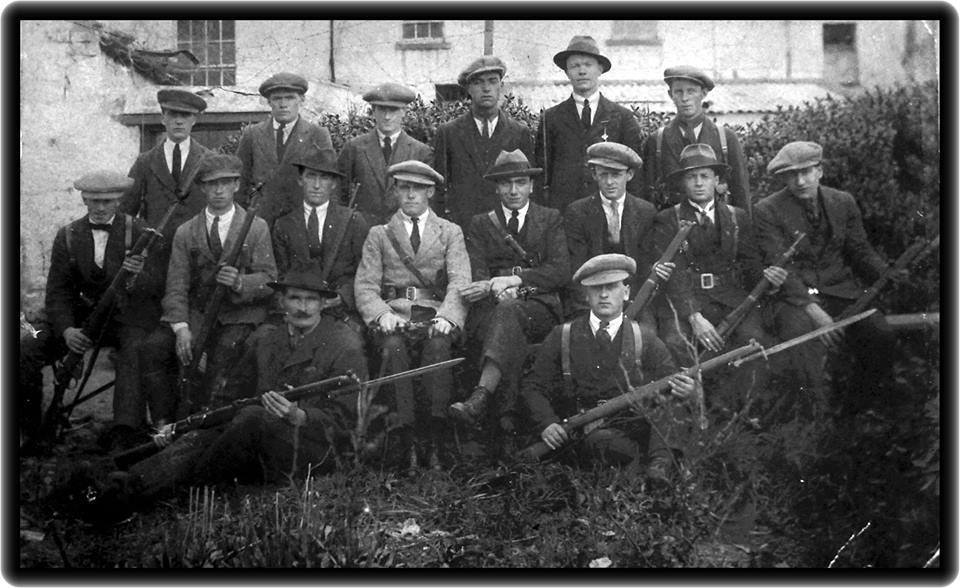

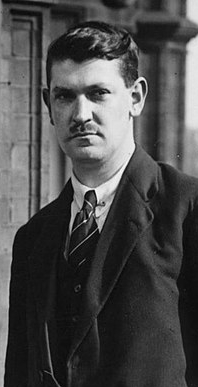

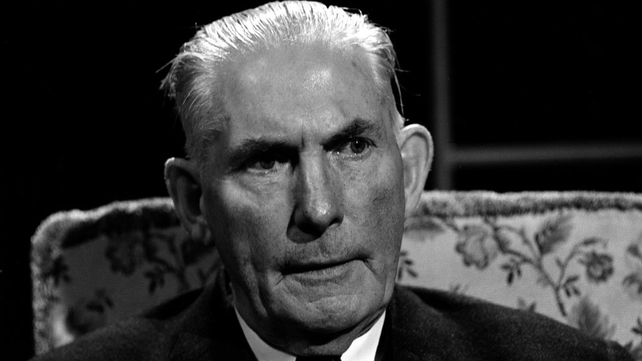

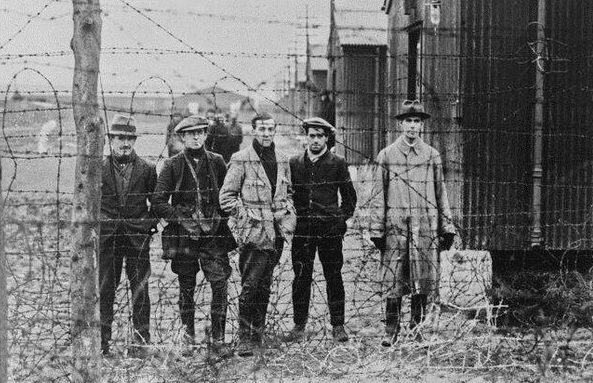

The dead man was later identified as Martin Savage, a former resident of Knutsford Detention Barracks, imprisoned there due to his involvement in the 1916 Rising, three and a half years previously. The attacking party soon fled, some on bicycles down Navan Road, in the direction of the city, others running through a field, all the while hotly pursued by soldiers – at least, that is how it was reported. According to Dan Breen, reading this in the newspapers was enough to send him into fits of laughter as the soldiers in the third car had actually driven on to the cover of the Phoenix Park wall after their initial exchange of shots. And Breen would have been in a position to know, having been one of the three men positioned by the cart with Savage, during which he had also been hit – though in the leg, making him luckier than Savage at least.

What is certain is that Breen and the rest did not stick around, having disappeared by the time more soldiers and policemen from the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) arrived. They found, in addition to the slain man, a wounded Constable Michael O’Loughlin. Whatever happened to him had occurred before the ambush was sprung. He was immediately placed in the second of the cars which, as damaged as it was, remained intact enough to drive the constable to Steevens’ Hospital, Kilmainham.

Also of interest was the farmer’s cart Rumble had seen three of the assailants sheltering behind. It would appear that its intended use was to be pushed into the middle of the thoroughfare, only for Constable O’Loughlin to chance upon the party and their cart while on patrol, as unexpectedly for him as it was for them. Which was just as well for Lord French, for, as the Irish Times darkly noted, “had they blocked the road and stopped the cars, they would have had them virtually at their mercy.”[3]

‘The Head of an Alien Government’

Which almost certainly would have meant the end of the Lord Lieutenant. Whether the War of Independence had started earlier that year, at the Soloheadbeg ambush on the 21st January 1919, or if it was just the latest stage in a process triggered by the Easter Week of 1916 – Savage, after all, had been a participant – is a matter of debate; what is clear is that the Volunteers of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) had been looking at ways to escalate their armed campaign against British rule in Ireland for quite some time.

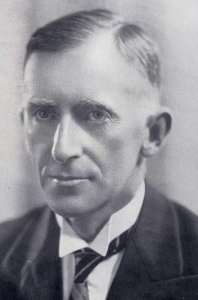

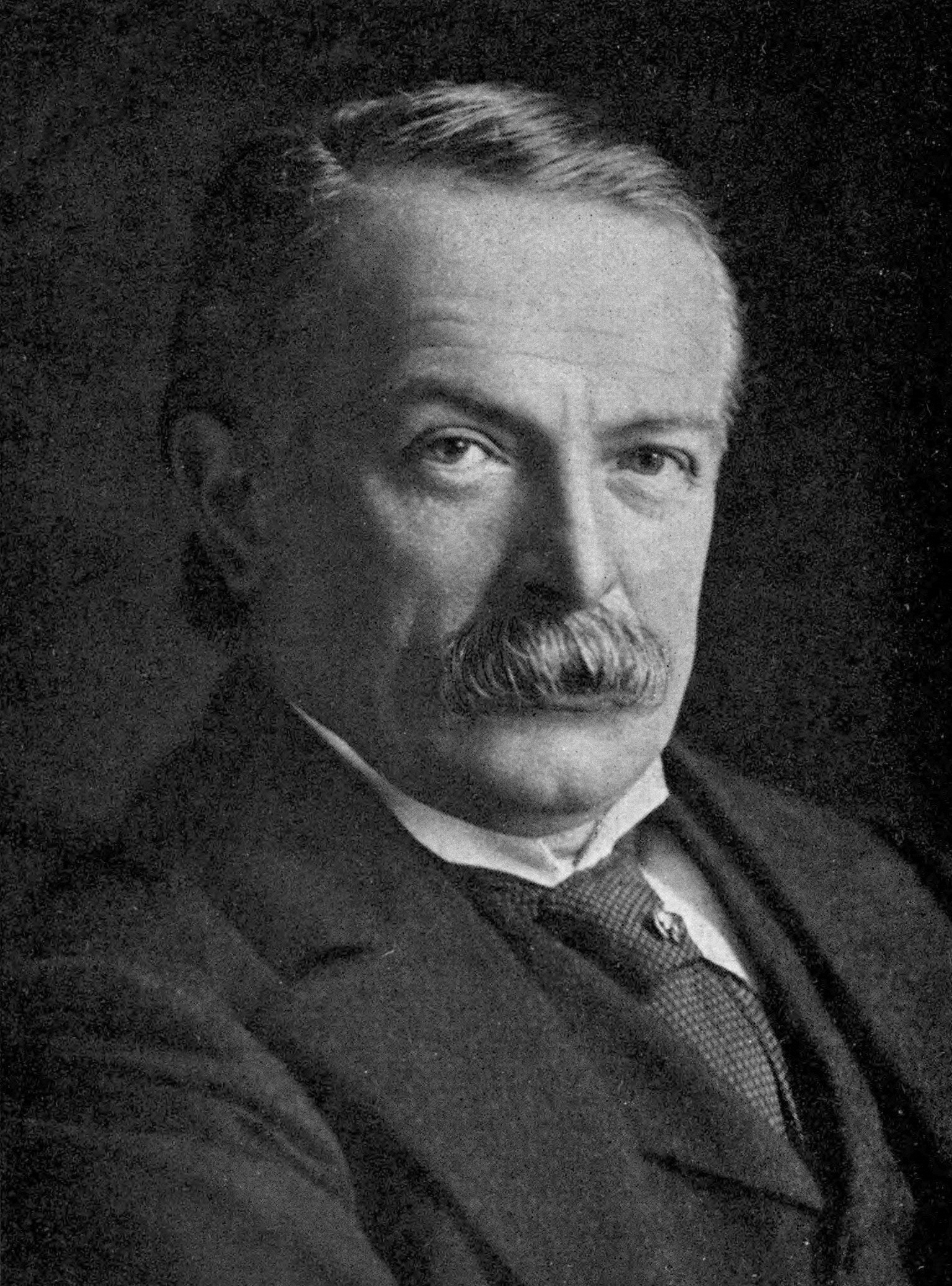

Mick McDonnell had been in London in the autumn to assess the feasibility of wiping out the British Cabinet and any other targets of note (a strategy first mooted during the Conscription Crisis of the year before and which would later be revived in 1921 as the insurgency was reaching its zenith). After two weeks in the enemy capital, McDonnell returned to Dublin to report to Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Cathal Brugha and other members of the IRA command. He recommended against the initiative as, other than the unlikelihood of catching the entire hit-list at once, anyone sent on the mission would not be coming back (though Brugha still seemed eager, that particular plan was quietly dropped). That was the same rationale against the next big idea, in November 1919: shooting Lord French while the Lord Lieutenant was taking the salute for the special victory parade in College Green, marking the one-year anniversary of the Armistice; meanwhile, IRA teams would be simultaneously striking the procession at different points.

When Dick McKee, while discussing this with McDonnell, asked for a choice of assassin – who, in theory, would snipe Lord French from a window in the adjacent Bank of Ireland, as if this was Dallas in 1963 – McDonnell could not provide one: the job was just too big. He eventually offered himself, despite knowing full well, as did McKee, that the mission would be a suicide one. “If I went down I would go down in glory,” was how McDonnell explained his thinking at the time. To his surprise – and probably relief – the scheme was cancelled the night before the parade as Brugha, a man not otherwise known for his moderation, “said the people would not stand for it” – civilian casualties, after all, would be hard to avoid.[4]

Regardless, from that point, the Lord Lieutenant became the IRA’s number one target – “GHQ wanted Lord French executed at any cost,” as McDonnell put it.[5]

It was, Breen stressed, nothing personal: “Against the old soldier himself we had no personal spite, but he was the head of an alien Government that held our country in bondage.” Besides, there was the potentially priceless publicity to consider:

We knew that his death would arouse the world to take notice of our fight for freedom. His name was known throughout the civilised world. The Phoenix Park was as famous as Hyde Park. Think of the sensation that would be created when this man, a Field-Marshal in the British Army, head of the Irish Government, was shot dead at the gate of the Phoenix Park, in the capital of the country he was supposed to rule…The citizens of every country would sit up and say: ‘The men who have done this are no cowards. Ireland must have a grievance. What is it?’ That is the result on which we reckoned.[6]

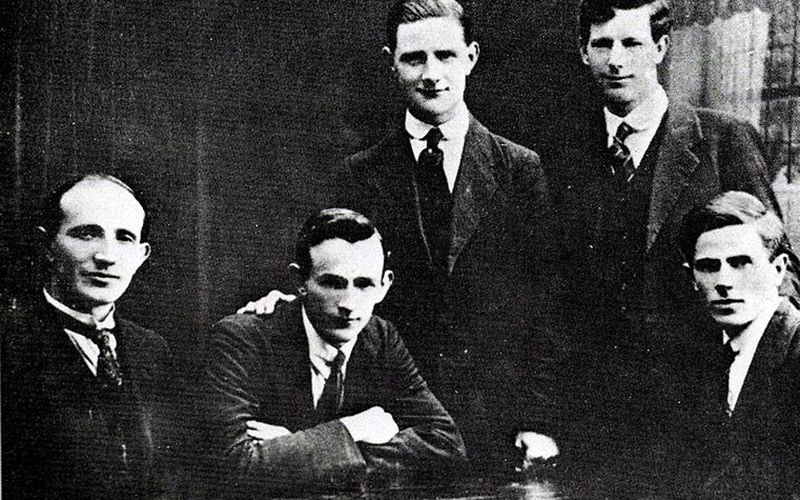

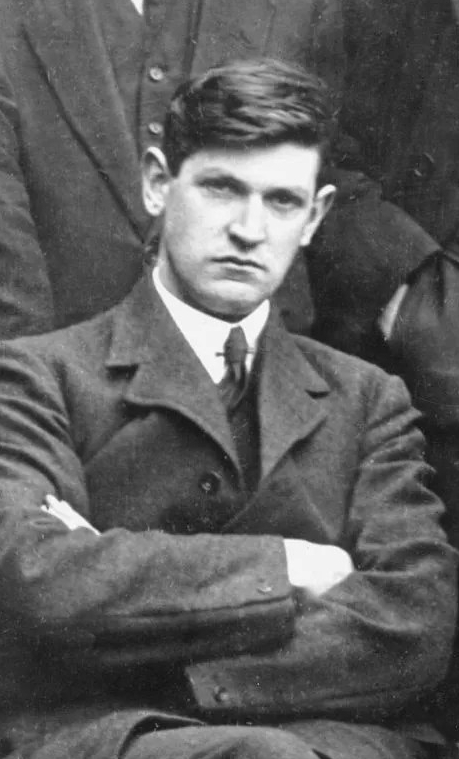

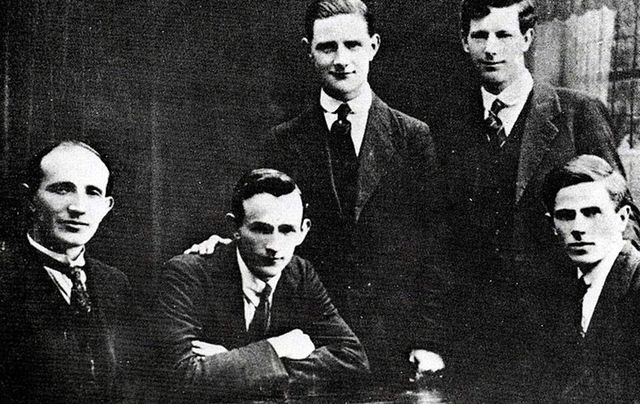

In truth, Breen was more concerned about the inhabitants of his own country, finding them, to his dismay, to be ambivalent about the IRA’s recourse to violence. Soloheadbeg had been as much to kick-start the overdue war as about robbing gelignite when Breen, Seán Treacy and other Tipperary Volunteers waylaid the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) escort and shot dead the two constables present. That was what Breen and Treacy, as Quartermaster and Vice-Commandant of the South Tipperary IRA Brigade respectively, had agreed between them. Both were spending too much time behind bars on one charge or another for their liking; it was time, Treacy remarked, to stop being pushed around and do a bit of pushing back.[7]

Instead of the ‘risen people’ Breen had hoped for after Soloheadbeg, “many people, even former friends, branded us as murderers,” a fact that still rankled by the time he put pen to paper for his reminiscences. An otherwise sympathetic priest compared from the pulpit the Soloheadbeg culprits to the Biblical Cain, while a farmer who allowed Breen and some others into his house ordered them back out into the cold night as soon as he learned they were armed. Such was the pressure that Breen and Treacy, along with Séumas Robinson and Seán Hogan who had also been at Soloheadbeg, decided to chance the big city together.[8]

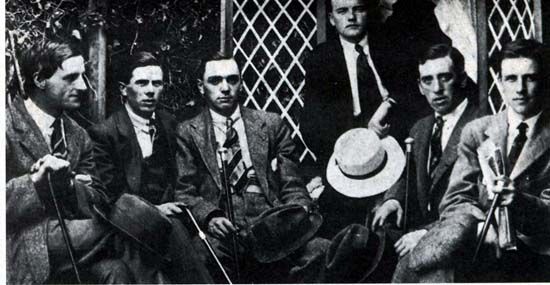

Their proven willingness to risk their lives and liberty for the cause was co-opted into the cadre of gunmen that was forming in Dublin – what would become known as the Squad – and assigned to the task of assassinating the Lord Lieutenant. Which was easier ordered than done: the experienced soldier that he was, Lord French proved an elusive quarry, often changing his plans at the last moment to thwart his enemy’s, such as when Breen was assigned with others to Grattan Bridge one chilly November night, a grenade in hand to hurl at the Lord Lieutenant’s car when it passed on the way to a banquet in Trinity College.

As Lord French failed to appear, all Breen and his companions got for their troubles was wasted time and frigid fingers. The same nothing happened a fortnight later on the same bridge which Lord French was again supposed to cross and again did not. As they stood in the snow, pacing the length of the bridge, the Volunteers realised how they stood out like a sore (and cold) thumb and hastily departed – just in time to avoid the lorry-loads of British soldiers who descended on the scene, stopping and searching everyone in sight. It was an unpleasant reminder that, while the IRA was gradually winning the streets, via the murder of selected DMP officials, Dublin remained dangerously unpredictable – for everyone.[9]

Misleading Statements?

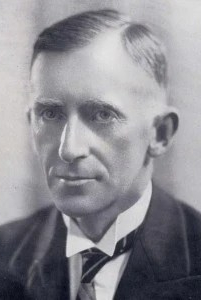

However readable Breen’s My Fight for Irish Freedom is, it must, like any autobiography, be treated with a certain caution. Not all contemporaries were overly impressed by it; Breen’s suggestion that the quest to kill the Lord Lieutenant originated from discussions between him and his three Tipperary comrades, with the Dublin Volunteers following their lead, prompted Piaras Béaslaí to inform readers of his own work:

In view of misleading statements, made in a recent publication [Breen’s book was published in 1924, two years before Béaslaí’s in 1926], it is necessary to emphasis the fact that the projected attack on Lord French was the unanimous decision of G.H.Q., and that reports as to his plans and activities in the matter were regularly submitted by Collins to meetings of Headquarters.[10]

Another divergence is how the IRA learned of Lord French’s arrival in Ashtown Station on the 19th December 1919. According to Breen, “our information had come from a trusted agent inside Dublin Castle” – one of the several DMP moles Collins had working for him, such as Eamon Broy, who was to identify himself (if indirectly) as the source in question:

Several times, amongst the items I gave Tommy Gay [his link with Collins] were particulars as to where Lord French would be the following day, but nothing ever happened. One night, meeting Tommy in the usual way, and having told him a few things, I mentioned casually that Lord French would be arriving at Ashtown Station at 1 p.m. on the following day. I thought no more about it.[11]

McDonnell and Vincent Byrne, both of whom were present at the ambush, told a different story, albeit with variations between them (each as part of their Bureau of Military History [BMH] Statements, composed decades afterwards, so such discrepancies are to be expected). According to Byrne, he was in a Sinn Féin club at North Summer Street when Paddy Sharkey, who was part of the same Dublin IRA company as he, casually mentioned his need to leave early that night: his father, as a railway guard, was due to go down to Roscommon “to bring ould French back to Dublin” the next morning, with Sharkey needed to prepare his lunch for then.

“Oh, is that so?” Byrne replied, and went to McDonnell’s house as soon as he could to report this inside scoop.

McDonnell was to tell a similar story, except that it was Tom Ennis, not Byrne, who overheard the railway guard’s son and that the original information was when Lord French would be leaving Dublin, not returning to it. “We organised a squad, went to Ashtown Cross, waiting there all night, and French did not turn up,” McDonnell recalled. “When dawn started to break in the morning we went home tired, sleepy and hungry, disgusted and disappointed.”

The information had been correct, it seems only that Lord French had enjoyed the party he was at in Frenchpark, Co. Roscommon, so much that he stayed the night. McDonnell resolved to get their target on the return journey instead, and obtained the new schedule from the railway guard’s son (that the young man may have been putting his father in harm’s way did not seem to have occurred to him). When McDonnell received the phone-call from Tom Ennis on the morning of the 19th December that the train due to carry the Lord Lieutenant was leaving Broadstone Station, he knew it was time to gather the men and get them into position at the chosen site of Ashtown Cross, between Ashtown Station and the Phoenix Park gate.

“I was in charge of that ambush,” he wrote, a claim supported by Byrne, who was told by McDonnell, in the front-room of the latter’s home where the handpicked team assembled that day, to go out and bring back any grenades he could find in the nearest weapons’ dump.[12]

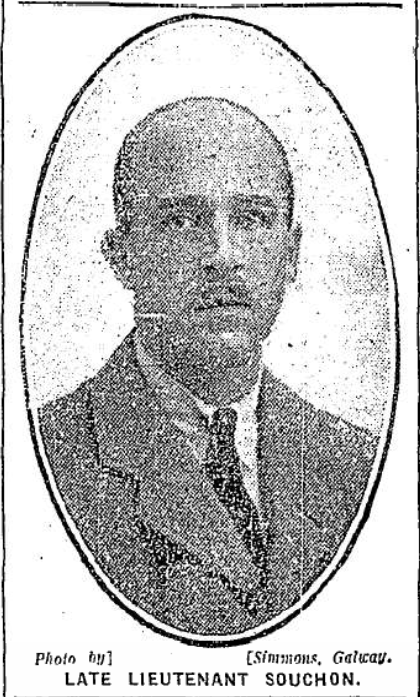

Constable O’Loughlin

Breen did not specify who was in charge, preferring instead to focus on his own experiences during the ambush. Historian Diarmaid Ferriter commented on how his memoirs “seemed more to popularise him than to provide any real insight or detached analysis.” A harsh critique, perhaps, but Séumas Robinson, for one, came to resent Breen’s glory-hound tendencies, using his BMH Statement to accuse the other man of inflating his war record and IRA rank. As O/C of the South Tipperary Brigade, Robinson had been Breen’s commanding officer – but one would never guess from My Fight for Irish Freedom that Breen had had any such thing.[13]

Similarly bold, or brash, was his assertion that they could have taken the train to Frenchpark, overpowered its military guard and killed the Lord Lieutenant then and there, before escaping with similar ease. Considering the difficulties Breen would encounter during the actual attempt, this claim should perhaps not be looked into too closely (in contrast, Byrne said he was “no Robert Emmet”, as in suicidal, when an earlier plan to catch Lord French on the grounds of the Viceregal Lodge was broached to him).[14]

The first complication arose when Constable O’Loughlin chanced upon Breen, Savage and Keogh as they waited by the road, cart at the ready to push out. In a sign that the IRA insurgency was still in its fledgling stage, the policeman tried moving them along rather than assume any malign intent; to Breen’s exasperation, O’Loughlin somehow failed to notice the two revolvers he was carrying. The constable would be found injured at the scene, though not from any action of Breen’s; besides having “no desire to kill the unfortunate man”, a gunshot would almost certainly blow their cover.

Instead, it was a fourth Volunteer – unnamed in Breen’s book – who left the spot he had been assigned to and threw a grenade at Constable O’Loughlin. As this meant endangering Breen’s life as well, it can be assumed this was done in a fit of pique:

The policeman was struck on the head with the bomb which burst at my side without inflicting injury; but the force of the explosion threw us violently to the ground. The policeman was not seriously injured. We quickly recovered from the shock and had no time to bother about the policeman.

The Lord Lieutenant’s convoy was almost upon them. Had Breen, Savage and Keogh got the cart in place, instead of being delayed by O’Loughlin, they could have prevented the first of the cars – the one, as it turned out, Lord French was inside – from speeding past with only a few strikes able to be made against it.[15]

The interfering constable appeared in McDonnell’s and Byrne’s BMH Statements as well, though not with any great explanation as to what happened to him. “We thought of taking him but thought again it would hamper our positon or maybe give the alarm, then decided to leave him alone,” wrote McDonnell, attributing instead the failure of the cart strategy to Breen and the other two pushing it shaft-first, not the easier way of body-first McDonnell told them to do.[16]

In Byrne’s version, it was Breen, Keogh and McDonnell – not Breen, Keogh and Savage as Breen told it – who were moving the cart, only for it to become stuck in a dip by the side of the road. Constable O’Loughlin appeared and disappeared in Byrne’s narration just as mysteriously as in McDonnell’s, with the former saying only: “The policeman stood in the centre of the crossroads, as a traffic man. I suppose he was there to see that his Excellency would have a clear passage.”[17]

Clearly, the ambush was a less-than-professional affair, and its various players had ample reason to omit or downplay certain aspects. As if Breen being almost killed by a ‘friendly’ bomb was not farcical enough, Seán Hogan fumbled one of his own, covering himself and Paddy O’Daly with dirt when it detonated between them. Had Hogan and O’Daly not thrown themselves to the ground in time, worse might have been inflicted. Michael Lynch was to blame the failure to kill the Lord Lieutenant on the grenades having overly long five-second fuses, when shorter ones for a second and a half would have been deadlier. Given the narrow escapes Breen, Hogan and O’Daly did have, however, the likeliest causalities would have been themselves.[18]

Exchanging Shots

Although too injured to appear at the subsequent inquiry, Constable O’Loughlin was able to make his side of the story known via a friend who repeated what the other man told him to the Irish Independent. According to O’Loughlin, he had been on duty at the crossroads, minding his own business, when a bomb passed over his shoulder, narrowly missing his head. “I did not know who threw, or if it was thrown at myself, because it was flung from behind,” the policeman said. “I had not noticed any suspicious-looking people around there. Everything appeared just as usual.”

Almost as if the first was a signal, more grenades were flung from a hedge on the roadside, while O’Loughlin heard the sound of several guns being fired; meanwhile, the first of the convoy cars was coming up the road. The constable was drawing his own weapon when the first bomb went off in front of him, albeit not to any great effect – to judge from all the accounts, IRA munitions-making skills was decidedly in the beginner’s stage – for O’Loughlin was still standing when he saw three men – described by the constable as being “all respectably dressed…not like labourers or in working clothes” – running towards him, guns in hand:

Before I could bring my revolver into action I got shot in the left foot. I was staggered and fell, and was just falling on the side of the road…The wound in my foot and the whole commotion of the shots and explosions all coming at once, must have stunned me, and I was dazed.[19]

The man who was to drive O’Loughlin to hospital, Corporal Appleton, had his own brush with death. As the man behind the wheel of the second car, as well as its sole occupant, he bore the brunt of the ambush. Two bullets struck the windscreen, followed by a bomb through the left-hand window, scattering fragments inside but leaving Appleton unscathed. As the Corporal stopped his car and looked out, he saw one of the attackers pointing a revolver at him with a cry of ‘hands up!’

Mr H.O. Holmes (Crown representative at inquiry): What did you do?

Appleton: I immediately fired a shot at him with my revolver. The escort car went by as I ducked down.

Holmes: How many shots did you fire at this man?

Appleton: About twelve. The revolver has six rounds, and I reloaded once.

Holmes: Did he fire back at you?

Appleton: Yes.

Holmes: How many shots did he fire?

Appleton: I could not say. We were exchanging shots, firing shot for shot till my ammunition was exhausted.

Holmes: What happened [to] him?

Appleton: He went clear round the corner [of a nearby building]. After my ammunition went, I had no more to defend myself with.[20]

This was a somewhat more heroic version than the one later provided by Byrne, in which Appleton – misnamed as ‘Applesby’ here – waved a white handkerchief in surrender. “Blown to bits in his car,” he said when questioned about the Lord Lieutenant, which the Volunteers took at face value. Someone then suggested Appleton be killed, to which another replied: “Oh, it’s not him we wanted,” thus saving the Corporal’s life.[21]

McDonnell corroborates this somewhat, in that they captured the second car and its driver, finding to their disappointment only luggage inside, with no Lord French. The debate on Appleton’s life is not included, however. Breen is briefer, writing only that “we left the constable [O’Loughlin] and the driver [incorrectly named ‘McEvoy’] on the field of battle,” while the version provided by another participant, Joe Leonard, matches the initial newspaper reports of the would-be assassins fleeing after being confronted with the soldiers in the third car: “We had not much time to spare, remembering the fifty [actually six] soldiers advancing on us, so all we could do for Martin Savage was to whisper a prayer” and leave the scene.[22]

Aftermath

Other than Savage’s death, there were three main consequences to the attack on Lord French:

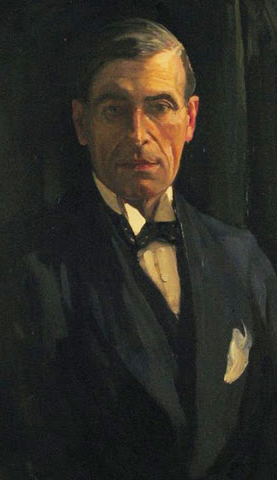

One – New measures to stamp out the nascent rebellion were accelerated by the authorities. Throughout his military career, Lord French’s “touch had never been light or deft when matters of internal security was concerned,” as even a sympathetic biographer admits, and “his deep own sense of Irishness did nothing to help him see the Irish problem in anything but the starkest of blacks and whites”; his appointment to Lord Lieutenant being a sign in itself at how the British Government “was fast running out of options” in its handling of an increasingly turbulent country.[23]

As Dublin Castle hesitated between applying the carrot or the stick, Lord French was very much of the latter option, successfully urging the Cabinet to proscribe Sinn Féin in July 1919, though London balked at his request for the right to impose martial law – that is, until the failed attempt on his life convinced enough wavering minds in government. A month later, in January 1920, the British Army began assuming greater responsibility in Ireland, turning a policing matter into a more military one, and with Lord French taking the chance to sign as many internment warrants as he could get.[24]

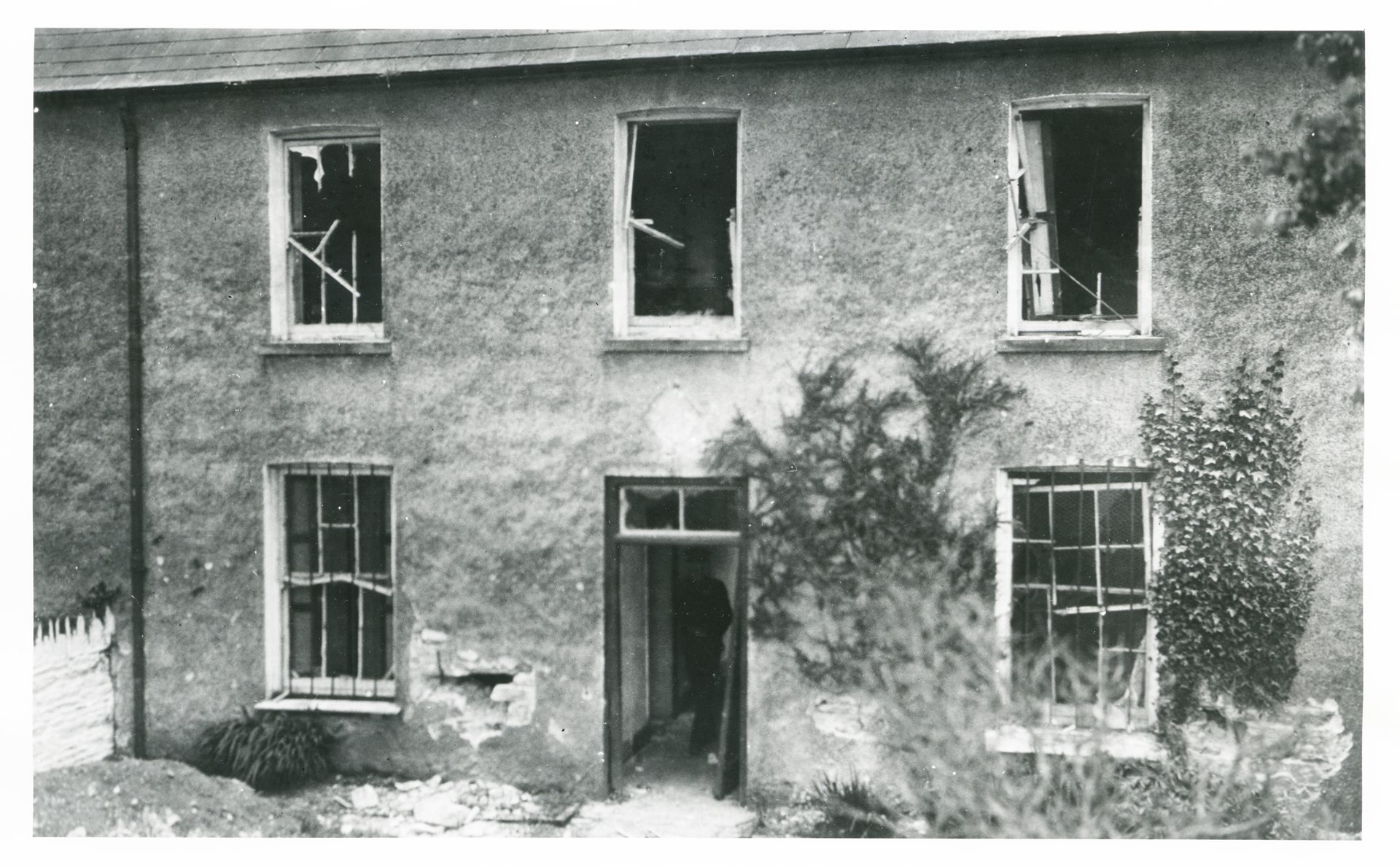

Two – Sufficiently offended were the Dublin Volunteers at the coverage of the Irish Independent, with phrases such as “this dastardly attack”, that it was agreed by Richard Mulcahy, the IRA Chief of Staff, that action could be taken against it. Guided by the advice of one of their number, who worked in the linotype room of the newspaper, an IRA raiding party entered the Irish Independent’s building and dismantled its printing machinery, enough to lose it a day of sales. Worse could have occurred: some of the Volunteers were on their way to murder the editor when stopped near Parnell Square by one of their officers, Michael Lynch, who insisted on them waiting for orders from GHA before doing anything.[25]

Mulcahy was to refer to this almost three years later, in April 1922, before Dáil Éireann. Ireland was by then a very different place, politically speaking, with the Lord Lieutenant and the rest of Dublin Castle out and the formerly underground body of Irish representatives in – and wrestling with a very similar set of challenges. Instead of the Irish Independent, it was the Freeman’s Journal’s turn to be wrecked by the IRA – except, rather than having ordered it as before, Mulcahy was obliged to explain why brutalising a media outlet was not okay now when it had been permissible then.

“As far as any action against the Independent is concerned,” he told the Dáil, “that was taken in order to save life purely and simply.” Had Mulcahy not permitted the Volunteers that outlet, their anger might instead have been taken out on the newspaper staff, fatally so. The opposition in the Dáil scoffed at this but, going by Lynch’s account, Mulcahy was speaking the truth.[26]

Three – As with Easter Week of 1916, the Ashtown Ambush was in execution a flop. While praising the “small handful of very brave men” behind it, Michael Lynch lamented how the operation had been “rushed into without proper military planning” and was to wonder what could have been done differently to save Savage’s life. However, again like Rising, the deed did much to publicise the policy of armed resistance to British rule – and showed there was a receptive audience.[27]

This was demonstrated at the inquiry into Savage’s death. After outlining the facts of the case, the Coroner urged the jury to find that the fatal shooting of Savage, in the act of pulling the pin out of a grenade he would then throw, was justifiable homicide on the part of the soldier responsible. Instead, after consulting among themselves for an hour, the jury members delivered a verdict coolly indifferent to the Coroner’s request, finding only “that Martin Savage met his death as a result of a bullet fired by a military escort at Ashtown Cross on the 19th December.” What was more: “The jury beg to tender their sympathy to the relatives of the deceased.”[28]

A turning-point had been reached, Breen crowed:

The people were beginning to appraise the situation. In private many defended our standpoint. The great majority of our countrymen were taking their bearings. Some of them were shocked at the daring force-tactics but it was becoming obvious to all that we meant business and that it was their duty to stand by us.[29]

And while there is much in Breen’s book to put a question-mark over, on that particular point, when read alongside the jury’s verdict, he was probably more correct than not.

References

[1] Irish Times, 20/12/1919

[2] Ibid, 23/12/1919

[3] Ibid, 20/12/1919 ; Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), p. 95

[4] McDonnell, Michael (BMH / WS 225), pp. 3-5

[5] Ibid, p. 5

[6] Breen, p. 84

[7] Ibid, pp. 31, 34

[8] Ibid, pp. 40-1

[9] Ibid, pp. 82-3

[10] Ibid, p. 81 ; Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland, Volume I (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008), p. 248

[11] Breen, p. 85 ; Broy, Eamon (BMH / WS 1280), p. 103

[12] Byrne, Vincent (BMH / WS 423), p. 16 ; McDonnell, p. 5

[13] Ferriter, Diarmaid. A Nation and Not a Rabble: The Irish Revolution 1913-1923 (London: Profile Books Ltd., 2015), p. 30 ; Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), pp. 127-9 (for more on Robinson’s and Breen’s chilly relationship, see A Bitter Brotherhood: The War of Words of Séumas Robinson

[14] Breen, p. 84 ; Byrne, p. 15

[15] Breen, pp. 87-8

[16] McDonnell, p. 6

[17] Byrne, pp. 17-8

[18] O’Daly, Paddy (BMH / WS 387), p. 21 ; Lynch, Michael (BMH / WS 511), p. 84

[19] Irish Independent, 22/12/1919

[20] Irish Times, 23/12/1919

[21] Byrne, pp. 189-9

[22] McDonnell, p. 7 ; Breen, p. 90 ; Leonard, Joe (BMH / WS 547), p. 7

[23] Holmes, Richard. The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2004), p. 337

[24] Ibid, pp. 350, 354

[25] Lynch, pp. 87-8

[26] Dáil Éireann. Official Report (Dublin: Published by the Stationery Office, [1922]), p. 322

[27] Lynch, p. 84

[28] Irish Times, 23/12/1919

[29] Breen, p. 93

Bibliography

Newspapers

Irish Independent

Irish Times

Books

Béaslaí, Piaras. Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland (Dublin: Edmund Burke Publisher, 2008)

Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010)

Dáil Éireann: Official Report (Dublin: Published by the Stationery Office, [1922?])

Ferriter, Diarmaid. A Nation and Not a Rabble: The Irish Revolution 1913-1923 (London: Profile Books Ltd., 2015)

Holmes, Richard. The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2004)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Broy, Eamon, WS 1280

Byrne, Vincent, WS 423

Leonard, Joe, WS 547

Lynch, Michael, WS 511

McDonnell, Michael, WS 225

O’Daly, Patrick, WS 387

Robinson, Séumas, WS 1721

Undeterred by this unpromising start:

Undeterred by this unpromising start:

As an historic source, his book has its flaws. No one who suggests that it was the IRA who murdered Tomás Mac Curtain for his supposed wavering or that Dick McKee, Peadar Clancy and Conor Clune were killed while assaulting their guards inside Dublin Castle (with a smuggled grenade, no less) can be read without the slightest raising of the brow. But Winter does clearly convey how the British counter-insurgency was not working on any sort of pre-approved system or formula, being instead an ad hoc, whatever-works-works process.

As an historic source, his book has its flaws. No one who suggests that it was the IRA who murdered Tomás Mac Curtain for his supposed wavering or that Dick McKee, Peadar Clancy and Conor Clune were killed while assaulting their guards inside Dublin Castle (with a smuggled grenade, no less) can be read without the slightest raising of the brow. But Winter does clearly convey how the British counter-insurgency was not working on any sort of pre-approved system or formula, being instead an ad hoc, whatever-works-works process. Too Many Cooks over a Broth

Too Many Cooks over a Broth

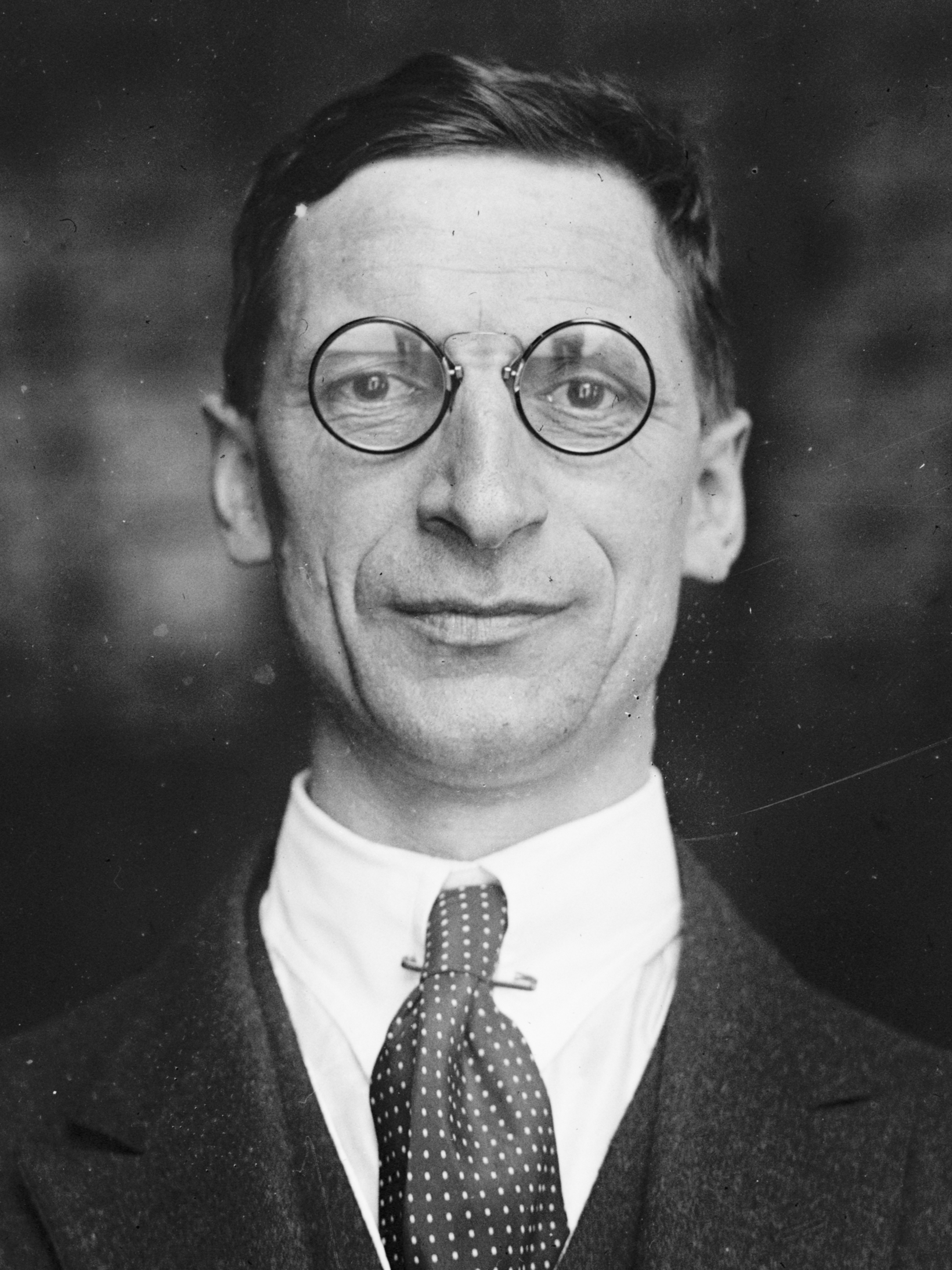

Another ambush that stirred post hoc controversy was Kilmichael on the 28th November 1920, when a force of eighteen Auxiliaries was nearly annihilated by the flying column of the West Cork IRA Brigade. Deasy was on familiar terms with the column and its commander, Tom Barry, accompanying it when not called away on staff work as Brigade Adjutant. It was while performing such duties in Crossbarry that Deasy missed the ambush, though he was able to use the testimony of one participant, Paddy O’Brien, in his narrative of the War of Independence, Towards Ireland Free.

Another ambush that stirred post hoc controversy was Kilmichael on the 28th November 1920, when a force of eighteen Auxiliaries was nearly annihilated by the flying column of the West Cork IRA Brigade. Deasy was on familiar terms with the column and its commander, Tom Barry, accompanying it when not called away on staff work as Brigade Adjutant. It was while performing such duties in Crossbarry that Deasy missed the ambush, though he was able to use the testimony of one participant, Paddy O’Brien, in his narrative of the War of Independence, Towards Ireland Free. That assumes, of course, that these feelings had been bubbling away all this time. Yet the evidence otherwise suggests that, until Towards Ireland Free, the two men had been on good terms. After all, Deasy praised Barry lavishly in his memoir, as had Barry with Deasy in his own, Guerrilla Days in Ireland, printed twenty-four years earlier in 1949. Which was hardly surprising, given how extensively the pair worked together in the West Cork Brigade. Barry had found Deasy to be “a tower of strength” and not only “the best Brigade Adjutant in Ireland” but “one of the best Brigade O/Cs” when promoted to that position. For Deasy’s part, he extolled Barry’s “enthusiasm and dynamism that were astonishing”, combined with “a remarkable grasp of military psychology” and culminating in “something greater still: he was a leader of unsurpassed bravery.”

That assumes, of course, that these feelings had been bubbling away all this time. Yet the evidence otherwise suggests that, until Towards Ireland Free, the two men had been on good terms. After all, Deasy praised Barry lavishly in his memoir, as had Barry with Deasy in his own, Guerrilla Days in Ireland, printed twenty-four years earlier in 1949. Which was hardly surprising, given how extensively the pair worked together in the West Cork Brigade. Barry had found Deasy to be “a tower of strength” and not only “the best Brigade Adjutant in Ireland” but “one of the best Brigade O/Cs” when promoted to that position. For Deasy’s part, he extolled Barry’s “enthusiasm and dynamism that were astonishing”, combined with “a remarkable grasp of military psychology” and culminating in “something greater still: he was a leader of unsurpassed bravery.”

Barry’s public vitriol at Deasy’s perceived slight was thus very personal, the anger of a betrayed friendship, and that feeling spilled out into the booklet he published as a sequel to his letter to the media. Titled The Reality of the Anglo-Irish War 1920-1921 in West Cork, with the pointed subtitle Refutations, Corrections and Comments on Liam Deasy’s Towards Ireland Free, the work went beyond the professional – one historical record set against another – to the personal with such spitefully worded phrases as ‘This disposes of one part of Deasy’s fairy tale’, ‘Deasy’s other hysterical statements’, ‘Deasy had the impertinence’ and ‘Deasy’s final chapter is equally incorrect’.

Barry’s public vitriol at Deasy’s perceived slight was thus very personal, the anger of a betrayed friendship, and that feeling spilled out into the booklet he published as a sequel to his letter to the media. Titled The Reality of the Anglo-Irish War 1920-1921 in West Cork, with the pointed subtitle Refutations, Corrections and Comments on Liam Deasy’s Towards Ireland Free, the work went beyond the professional – one historical record set against another – to the personal with such spitefully worded phrases as ‘This disposes of one part of Deasy’s fairy tale’, ‘Deasy’s other hysterical statements’, ‘Deasy had the impertinence’ and ‘Deasy’s final chapter is equally incorrect’.

But that had been then, and this was now, and the sundering they hoped to avoid had come after all. Which should not be Labour’s concern, said O’Shannon, as he urged his audience:

But that had been then, and this was now, and the sundering they hoped to avoid had come after all. Which should not be Labour’s concern, said O’Shannon, as he urged his audience:

“When the present issue was decided between Free Staters versus Republicans, then the time would come to launch their policy,” but, until then, Keyes:

“When the present issue was decided between Free Staters versus Republicans, then the time would come to launch their policy,” but, until then, Keyes:

Irish Times, 4th March 1921:

Irish Times, 4th March 1921: