A continuation of: The Chains of Trust: Liam Lynch and the Slide into Civil War, 1922 (Part II)

‘This Pure-Souled Patriot’

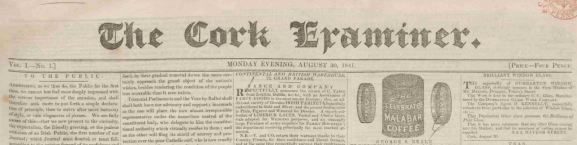

On the 8th July 1922, the Free State newspaper – the title of which left no ambiguity as to its allegiance – published a scathing account of Liam Lynch, Chief of Staff of the enemy forces, and his actions while leaving Dublin the month before. Under the provocative headline, THE HONOUR OF THE IRREGULARS – RELEASE OF MR. LIAM LYNCH, the article told how:

Mr Liam Lynch, on the outbreak of hostilities, did not join his command in the Four Courts. He was arrested by the National troops and taken to Wellington [now Griffith] Barracks. He was released on giving his word of honour that he disapproved of the policy of the Irregulars.

That was not the only promise he gave that day, according to the article: “Later he was again arrested at Castlecomer [Co. Kilkenny], and again released on giving a similar understanding.” And yet, almost immediately afterwards, Lynch resumed his post as Chief of Staff of the anti-Treaty Irish Republican Army (IRA), complete with a declaration of war against the Free State.

“Is further comment on this pure-souled patriot necessary?” the newspaper concluded with a metaphorical curl of the lip.[1]

Lynch did not take this affront lying down. Writing to the Cork Examiner four days later, he began by taking exception to being referred to as ‘Mr’ without the dignity of his military rank. As for repudiating the behaviour of his anti-Treaty compatriots, Lynch insisted that nothing could have been further from the truth.

Not only had he defended the actions of the Four Courts garrison, he wrote, he had told his captors in Wellington Barracks that he reserved the right to take whatever action he thought proper. That would be even if it meant defying the Provisional Government, the madness of which “would become even more evident when hundreds of more lives would be lost.”

Any supposed assurances given in Castlecomer were likewise fiction. Lynch blamed Eoin O’Duffy, his opposing counterpart as Chief of Staff of the National Army, for the spreading of these “contemptible inaccuracies”:

It would not be necessary to reply to this low propaganda were it not intended to hit the Republican Army command and undermine the confidence of the rank and file…It is horrifying and deplorable to find such despicable slander coming from those who betrayed not only their pledged word, but also the natural trust reposed in them.[2]

What exactly had been said in Wellington Barracks would remain a controversy. Liam Deasy would provide his own version of events, beginning with how he and Lynch were awoken in the Clarence Hotel by the pounding of the Free State artillery against the nearby Four Courts on the early morning of the 28th June 1922.

A Meeting…

Lynch quickly called a meeting in the Clarence with what colleagues of his were at hand, which included Éamon de Valera and Cathal Brugha. Given how he had been at loggerheads with the men in the Four Courts such as Liam Mellows and Rory O’Connor until the night before – when the two anti-Treaty factions agreed to bury the hatchet – it was necessary to affirm, after a brief discussion, that they would support their besieged IRA comrades.[3]

That this was discussed at all would indicate it had been no certainty. Those inside the Four Courts had also expressed their doubts. While discussing the best courses of action in the event of an increasingly plausible attack, Mellows had admitted that he did not know what their reappointed Chief of Staff would do. He believed Lynch would indeed fight but not necessarily in time to aid them.[4]

Todd Andrews was less convinced. As he hurried to Sackville (now O’Connell) Street to join the rest of the Dublin Brigade – unaware of the reconciliation on the evening prior to the attack – he thought it unlikely that Lynch would bestir himself to relieve the Four Courts, considering how he and his adherents “had been virtually expelled from the IRA Executive” following the acrimonious convention on the 18th June.[5]

But, according to Liam Deasy who knew Lynch well, this help was never in doubt. “I have always felt that his promise to support the Four Courts garrison if they were attacked remained a sacred trust,” he wrote later. “He was to the very end an idealist with the highest principles as his guide.”[6]

This did not mean, however, that Lynch would stay in Dublin to help. Even assuming he could make it past the siege lines of soldiers, barricades and artillery surrounding the Four Courts, he had no desire to be boxed in. Nor did it occur to him to contact the other anti-Treaty units in the city. Instead, he instructed each IRA man present to retire to their own command areas in the country and wage their share of the fighting from there.

It was a strategy in keeping with his instincts as a seasoned guerrilla: if in doubt, retreat and regroup. Besides, his powerbase had always been the First Southern Division and until he returned to it in Munster he would be unable to take the lead in the fight – and there was nowhere else he intended to be.

…An Interview…

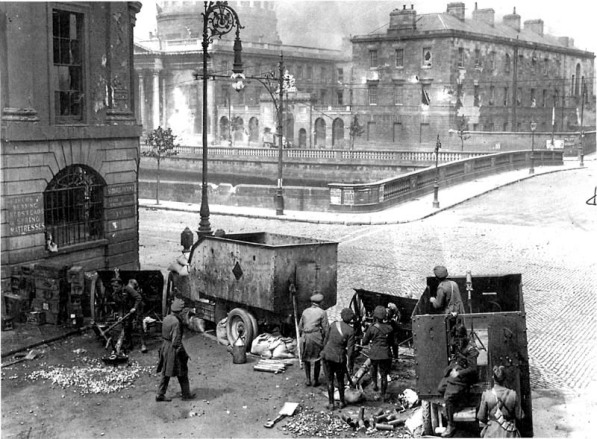

After a hasty breakfast, Lynch and Deasy set out with four others – Seán Moylan, Moss Twomey, Con Moylan and Seán Culhane – in two jaunting cars for Kingsbridge (now Heuston) Station. Passing by Parliament Street, they were spotted by Emmet Dalton, a Major-General in the National Army, from where he was directing the artillery against the Four Courts. Dalton instructed Liam Tobin, one of Michael Collins’ famous ‘Squad’, to overtake the vehicles and bring their passengers to Wellington Barracks.

Deasy had known Tobin from his many visits to Dublin during their mutual fight against the British. Reuniting with a brother-in-arms, now garbed in the uniform of the enemy, was an unpleasant reminder to Deasy of how much things had changed:

In later years I have often wondered on that meeting on the quays with a friend whom the fortunes of war had placed in a most invidious position. Being the soldier that he was he had no option but to do his duty as he saw it although I am sure his heart was not in it.

Meanwhile, there were those who were wondering as to where Lynch’s and Deasy’s own hearts were. Inside the Barracks, Lynch was removed from his companions and returned a few minutes later. Before he could say a word to Lynch, Deasy was taken in turn to a room where O’Duffy was waiting. The enemy Chief of Staff gestured for his ‘guest’ to take a seat.

What followed was one of the briefest interviews in Deasy’s life, recreated in his memoirs as such:

O’Duffy: This war is too bad, Liam.

Deasy: Yes, indeed it is.

O’Duffy: Where were you going when Liam Tobin met you?

Deasy: To get a train at Kingsbridge for Mallow [Co. Cork].

O’Duffy (standing up): Ah, you had better be on your way.

O’Duffy offered his hand. The two men shook and, with that, the six Anti-Treatyites were allowed to catch their train out of Dublin.[7]

…And a Meal

Lynch and the others reached the end of the train line at Newbridge, after which they commandeered a Buick motor – or stole, to be more prosaic, a common hazard of being a car owner during that period. Despite their caution in avoiding the main road in favour of a more circuitous route, they were held up yet again while driving into Castlecomer.

The officer in charge of the National Army patrol politely asked them where they were going. No mention was made of the war that had started less than a day ago. When the officer invited them to a meal at his barracks, Lynch demurred until Deasy reminded him that they had not had a bite since their rushed breakfast at the Clarence Hotel.

At the barracks, the visitors ate with their Free State hosts, both sides reminiscing freely with each other, speaking with nothing but regret at the current sorry situation. By midnight, the six Anti-Treatyites were in the process of leaving when one of the soldiers pulled out a sheet of ruled foolscap and asked for their autographs as a memento. Carried away by the feelings of goodwill, they agreed without hesitation. After a round of hearty handshakes, Lynch and his cohorts departed into the night and continued their journey westwards.

A few days later, Deasy was startled to read an official pronouncement from the Provisional Government, stating that he and Lynch had assured O’Duffy of their neutrality, with no intention of partaking in the fray. Their signatures – the same ones they had given at Castlecomer Barracks – were used as ‘proof’ of this agreement.

For Deasy, “this kind of vile misrepresentation” was made all the more painful by having been inflicted by fellow countrymen. The sickly realities of civil war, in which nothing was off-limits and the closest comrades made the bitterest foes, had yet to sink in.[8]

‘I Think Ye’re All Mad’

Despite having sat on the IRA Executive, Florence O’Donongue would abstain from the conflict. But he stayed on close terms with Lynch, and when it came to writing a biography of his former commander and old friend, he was determined to set the record straight. O’Donoghue was certain that such aspersions about Lynch’s conduct were no more than “bad examples of the regrettable propaganda material of the time.”

Still, no one disputed the fact that Lynch had been taken under duress to Wellington Barracks and then quickly released. The denial that Lynch would ever dissemble to escape a bind relied on the premise that O’Duffy would be negligent enough to turn loose a top-ranking adversary with no strings attached.

In trying to make sense of this peculiar turn of events, O’Donoghue ventured a guess that O’Duffy may have judged it prudent not to keep his unwilling guests detained, “believing that the confidence or goodwill thereby shown might have the effect of limiting the spread of civil war to the south.”

Deasy added nothing in his memoirs about what, if anything, Lynch had told him about his time in Wellington Barracks. It was left to O’Donoghue to try and fill in the blanks: apparently, Lynch had told Seán Moylan (who presumably passed this on to O’Donoghue) when they reached Kingsbridge Station that O’Duffy had merely asked him what he thought of the situation.

Lynch had replied: “I think ye’re all mad.”

The claim that he had broken his word may have been the result less of malicious slander and more a misunderstanding, with O’Duffy thinking erroneously that Lynch had been referring to the Four Courts garrison as the reckless ones.[9]

Emmet Dalton certainly thought O’Duffy had believed Lynch had assured him on his neutrality. Dalton was with Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy when O’Duffy “made it quite clear that Lynch had given an undertaking that he would not take up arms or take any active part against the Government forces.”[10]

Lynch had always been the man with whom the Pro-Treatyites could negotiate. Mulcahy had suggested enlisting his help during the Limerick stand-off in February/March earlier that year. O’Duffy had sat with him at the Mansion House in May to arrange a truce and the chance of further talks. In view of these precedents, the idea of Lynch continuing to exert a moderating influence was not an unbelievable one.[11]

Lynch’s subsequent declaration of war against the Provisional Government showed that any good will on O’Duffy’s part had been embarrassingly misplaced. Lynch might have deplored the ‘despicable slander’ but the other man’s sense of betrayal may equally have been genuine.

Instructions

Two days after leaving Dublin, Lynch made his intentions known in an open letter to IRA forces, published the following day in the Cork Examiner. The newspaper had been taken over by the local Anti-Treatyites for their own ends, prompting the editor to inform his readers that anything appearing under such headings as ‘Republican Army – Official Bulletin’ was not under his control and had nothing to do with him.[12]

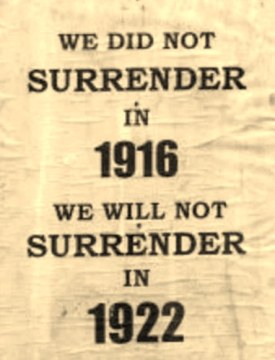

Lynch began with a notice that he was setting the record straight:

Owing to statements in some newspapers and general false rumours among the Army, I deem it necessary that all ranks should know at once the position of the Army Council.

He referred to how the IRA Executive had “recently differed in the matter of policy which was brought about by the final proposals of Minister for Defence [Mulcahy] for Army unification,” the first and only time he would publicly comment on the quarrel between him and the likes of Mellows and O’Connor that had briefly seen a split-within-a-split.

While he had stood down as Chief of Staff, the attack on the Four Courts had driven him into resuming his duties. A different leader may have couched his words to be more appealing to the general population, and not just as an address to his soldiers, but Lynch had never been overly concerned with matters outside of military ones.

Lynch expressed optimism that the trouble would soon be resolved in a way satisfactory to him and his fellow Anti-Treatyites:

By this evening we hope to have made rapid progress towards complete control of the West and Southern Ireland for the Republic. Latest reports from Dublin show that the Dublin Brigade have control of the situation, and reinforcements and supplies have been despatched to their assistance.

Lynch may have been misinformed. He might have been trying to brazen out a beleaguered situation. As it would turn out, Dublin was very far from being under control – complete or otherwise – as would be the West or South. Of course, military commanders tend not to admit to news detrimental to morale but, as would become apparent, Lynch was fully capable of believing even the most far-fetched prognosis as long as it chimed with his wants and desires.

Lynch ended on a note that would prove more hopeful than authoritative: “I appeal to all men to maintain the same discipline as in recent hostilities, and not interfere with civilian population except absolute military necessity requires it.”[13]

Peace and War

Lynch had made it clear who was in charge of the IRA. Not all of his subordinates were so sure. As he waited in the Four Courts, listening to the enemy guns pounding away, Peadar O’Donnell had hoped that the rest of the country would “rear up and smash the chain around us.” It did not. Things would have been different, O’Donnell was sure, “if the Army had been organised and properly led.”

It had not been. O’Donnell laid the blame for these failings on Lynch. While a good person, he did not, in O’Donnell’s view, possess a “revolutionary mind” and lacked the mental agility to “descend from the high ground of the Republic to the level of politics.” This obtuseness was shown in how, while making his way south from Dublin, “his only message to us was that he was not thinking of war, but of peace.”[14]

Lynch had been negotiating only a month before with Mulcahy for the possibility of a reunited Army. This had come to a crashing halt at the IRA Convention on the 18th June when a large chunk of attendees had walked out rather than accept such a compromise. But the possibility of a peaceful solution had been so tantalising close that it is perhaps unsurprising that Lynch would still hold out for bridges to be not yet burnt.

However admirable, this hesitant attitude of Lynch’s left his subordinates with no clear sense of direction. Confusion and helplessness would be the common threads in the stories of those Anti-Treatyites caught in the wake of the war’s outbreak.

Dan Gleeson was at home on leave in Co. Tipperary when he heard about the Four Courts. He hurried to Roscrea Barracks in time to find his company evacuating with orders to head to Nenagh, where fighting had broken out, and reinforce their allies there. By the time they reached Nenagh, its garrison was already in the process of withdrawing. With no further idea of what to do, the O/C of Gleeson’s unit simply gave up and took no further part in the war.[15]

Tomás Ó Maoileóin had witnessed with distaste how the Free Staters had moved to take key positions in Limerick. An agreement between Lynch and Mulcahy in March 1922 had prevented the escalation into violence, but the underlying tensions remained simmering. A prominent guerrilla against the British, Ó Maoileóin looked down his nose at the fondness of his pro-Treaty contemporaries for their smart green uniforms, Sam Browne belts and other professional trappings. To Ó Maoileóin, these were the vanities of a mercenary army, not one worthy of the nation.

He was in Cashel, Co. Tipperary, for a meeting of the Second Southern Division when the news from Dublin reached his ears. He wanted to call for an immediate response, certain that that victory was at hand if they acted swiftly. Imprisoned soon afterwards, Ó Maoileóin would brood on those missed opportunities for a long while to come.[16]

Dublin on Its Own

Séumas Robinson had first-hand experience of hitting the brick wall that was Liam Lynch. Not that the O/C of South Tipperary Brigade could claim to be particularly open-minded himself. A hardliner on the IRA Executive, Robinson had sided with those who barred Lynch and his coterie from the Four Courts immediately after the June Convention for refusing to renew the war with Britain (Lynch was not one to bear a grudge, as he would later promote Robinson to leadership of the Second Southern Division).

The inability of many on the anti-Treaty side to tolerate a different point of view struck again when Robinson criticised the foolishness of having them all holed up in the Four Courts like so many eggs in a basket. After a heated row with Rory O’Connor and Liam Mellows, Robinson stormed out the day before the shelling began, narrowly avoiding being trapped inside with the others (which illustrated his point, but he had no time for a ‘told you so’).

His command being in Tipperary, Robinson had little choice but to leave Dublin as soon as he could. He chanced upon Lynch on the train going out and was delighted to learn of the decision made in the Clarence Hotel to pick up the fight against the Free Staters.

That was to be one of the few points on which he and Lynch would agree. The two had never been particularly close even before the Convention fiasco, and Robinson was dismayed at the other man’s strategy of having each IRA unit remain rooted to its home patch, reacting only to whatever came their way. Robinson desperately wanted Lynch to muster their forces and advance on Dublin to stamp out the Free State for good, but Lynch would not budge from his chosen course of action.

Not wanting yet another split, Robinson instead offered his resignation. Lynch would not accept that either. The two were at a standstill. Robinson tried the sympathy card, telling how it had felt in the Easter Rising six years ago, left stranded in Dublin by the rest of the country. Still, Lynch remained unbending, fearing – Robinson thought – that the city would be too difficult to enter.

Robinson tried a compromise – a novelty within the Anti-Treatyites. He would send a hundred of his Tipperary men to Dublin to prove it could be reached. Robinson had not the slightest doubt in that regard and counted on Lynch being persuaded to switch to the more proactive approach that Robinson wanted.

Yielding a little, Lynch agreed for the aforementioned number to go. Robinson reciprocated by withdrawing his resignation. A hundred men were duly dispatched but Lynch was not to change direction as Robinson had hoped. No further support was issued and the Tipperary reinforcements eventually withdrew, leaving their Dublin colleagues to fend for themselves.

Years later, Robinson was still bitter. “For the second time in six years Dublin was let down at a critical moment by the rest of the country,” he lamented.[17]

Robert Brennan

Meanwhile, Lynch was seething over a complaint of his own. As the anti-Treaty leadership regrouped in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, Lynch griped to Robert Brennan: “I gave no promise of any kind. They wanted me to but I refused. How can they tell such lies?”

Brennan was surprised at how personally Lynch was taking it. Still, whatever resentment Lynch had with the Provisional Government, he did not hold it against its soldiers. To the contrary, he insisted the prisoners the IRA had taken be served the same food as them, while granting them the freedom of the barracks and even refusing to have them questioned for information. The idea that they would report on their colleagues offended him as much as the suggestion he had broken his word.

“They wouldn’t do it anyway,” he said, closing the topic.

“All very magnificent,” said an unimpressed Moss Twomey in a dry aside to Brennan, “but it’s not war. We’re losing because the fellows are not fighting. We’re firing at their legs.”

Brennan did not have much to contribute in that regards. While he had begun as a military man, commanding the Wexford Volunteers during the Easter Rising, afterwards he served in a more administrative capacity, first as the Sinn Féin Press Bureau and then Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs on behalf of the Dáil Éireann. As part of his role in the latter, he had been in Berlin to promote the cause of Irish independence until news of the Treaty caused him to resign in protest.

As with Lynch and Robinson, Brennan had fled Dublin upon hearing the pounding of the artillery. He found Lynch in Clonmel Barracks, putting the finishing touches to a map through which a line of flags from Limerick to Waterford had been inserted. South of the line were areas held by the Anti-Treatyites, while the north and east lay in Free State hands.

Also with him were Éamon de Valera and Erskine Childers. De Valera read enough in the map to be convinced on what must be done. He took Brennan and Childers to another room and told them that now was the time to make peace while they still had territory with which to negotiate.

As de Valera went through the list of possible peace terms he had been mentally compiling, Brennan could see from Childers’ expression that he thought little of such offers. Brennan was in silent agreement, thinking that the horse had already left the stable. The Pro-Treatyites were in the ascendant and would hardly bother with anything short of unconditional surrender.

None of them considered it worthwhile to ask the Chief of Staff what he thought. That de Valera had waited until out of Lynch’s presence was telling enough. With nothing else to do, Brennan and Childers strolled through the barracks, where they witnessed the predatory behaviour from many of the anti-Treaty troops there.

Men drove in on lorries with boxes labelled ‘shirts’, having been ordered to commandeer some. When opened, the boxes were found to contain women’s blouses. While disappointed, the soldiers were not overly concerned with returning them, since the shopkeepers, as one man sneered, “are all Free Staters anyway.”

Jumping at Shadows

After being told that there was no space for them in the barracks, Brennan and Childers retired for the night to a hotel in town, only to be awoken from their beds by the commotion of the military men making ready to depart. A report had come that the Pro-Treatyites stationed in nearby Thurles were on the move and threatening to surround Clonmel. As in Dublin, Lynch chose to wait for a more opportune time than risk a confrontation not of his choosing.

Cramped in the back of a lorry, shivering against the chill morning air, Brennan and Childers endured the ride. With them was Twomey, singing Sean O Duibhir an Gleanna, its melancholic refrain of ‘We were worsted in the game’ doing nothing for Brennan’s spirits.

After decamping in Fermoy, Co. Cork, they learnt over breakfast that there had been no danger after all. As it turned out, Lynch had previously dispatched a company of men to capture Thurles, only for them to be caught and overwhelmed in an ambush. News of the defeat came accompanied with the panicked warning that the victorious Free Staters were now advancing in turn. Once the confusion had been cleared up, Lynch was able to quietly send another force to reoccupy Clonmel.

For all the mishaps, crime and banality, Brennan could not help but be impressed by the man at the centre of it all:

[Lynch] was a strange young man to be at the head of a rebel army…He was handsome, in a boyish, innocent way. His large blue eyes and open countenance indicated his transparent honesty. His looks, bearing and presence might have belonged to a single-minded devoted priest.

He had come to be the chief warrior in the most turbulent section of the country through his fearlessness and daring and his ability to command respect…without any training or experience, he had discovered in himself wonderful military qualities. But his heart was not in this fight of brothers.[18]

Lynch dispatched Brennan to Cork to make the necessary propaganda additions to the Cork Examiner (he was later to be the IRA Director of Publicity). As the majority of newspapers were for the Treaty and the Provisional Government, the strong-armed Examiner was one of the few media outlets that Lynch could utilise.

“We are doing our utmost to get [the Cork] Examiner up along the East and if possible to Dublin,” Lynch wrote to Ernie O’Malley on the 13th July, the latter having been assigned to reorganise the IRA remnants in the capital. He advised O’Malley that “even one copy which will be sent daily should be copied for use in Dublin.”[19]

“We are doing our utmost to get [the Cork] Examiner up along the East and if possible to Dublin,” Lynch wrote to Ernie O’Malley on the 13th July, the latter having been assigned to reorganise the IRA remnants in the capital. He advised O’Malley that “even one copy which will be sent daily should be copied for use in Dublin.”[19]

The Power of Belief

While in Cork, Brennan stayed in the house of Mary MacSwiney. A diehard republican, she lambasted her guest when he faltered in confidence by suggesting that Cork might possibly fall. Brennan refrained from pointing out to her that Waterford had already been taken, with their side in no position to respond. The Anti-Treatyite defence across Ireland was looking as flimsy as the flags Lynch had stuck on his map.

Cork was still untouched by the conflict, giving the city the deceptive feel of an oasis of peace amongst the mayhem elsewhere in the country. But Brennan had seen on the faces of the people in Fermoy, Mallow and other towns a sullen resentment. The IRA was no more than another occupying army as far as they were concerned. Brennan guessed that de Valera had noticed it too, hence his urgency for some sort of settlement before things could spiral further out of control.[20]

But there was no point trying to tell that to the likes of Lynch or MacSwiney. An unshakeable self-belief to the point of delusion had crept into the anti-Treaty leadership, with doubters and dissenters helpless to intervene.

The Depths of Conviction

Perhaps Lynch did not notice the same hostility that Brennan saw. Maybe he simply did not care. He had not before about what the masses thought.

He had been infuriated by those fair-weather patriots who had made themselves heard only when the Truce had taken effect. “I don’t give a damn about those people when it comes to praise or notoriety, and they are making the hell of a mistake if they think I forget their actions during the war,” he wrote resentfully to his brother Tom. “I remember at one time in the best areas where it was next to impossible to find a bed to lie on.”[21]

(He may have gone further in his sentiments – or not. In July 1922, he was quoted as telling a Free State officer during a parley in Limerick that: “The people are simply a flock of sheep, to be driven any way you choose.” However, as the source for this line was O’Duffy, who had shown himself to be not above spreading pernicious stories, this has to be taken with a pinch of salt.[22])

Only with the military did Lynch seem content. Perhaps, thought O’Donoghue, “because there he had tested the sincerity of men’s faith and the depths of their convictions. He had not found them wanting.”[23]

Worldly Wisdom

Another friend, Todd Andrews, came to a similar conclusion. He would serve as Lynch’s adjutant, allowing him to study his Chief of Staff up close. As Andrews saw it, Lynch had dedicated his life to the IRA and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), and those two organisations had in turn defined him. “It was within the confines of these organisations, their objectives, their methods, their traditions, their personalities that Liam Lynch’s character developed,” Andrews wrote, and this was perhaps to Lynch’s detriment:

The formative influence exerted by the IRA and IRB was capable of creating very strong characters but these bodies were not capable of supplying the worldly wisdom so necessary to leadership in either politics or in war.[24]

Andrews thought of Lynch as not only without guile but being too innocent to see it in others. Of course, Lynch would not have succeeded as a guerrilla leader during the War of Independence had he been a complete babe in the woods. It might be truer to say that complacency, rather than naivety, was his chief flaw.

A Munster man to the core, Lynch was content to bide his time and manage his forces on home territory. Perhaps he had not intended to abandon Dublin and the Anti-Treatyites still fighting there but that was what he had done all the same. Instead, he preferred to regroup in the parts of the country where he was most comfortable, showing little signs of haste or urgency as he stuck his pins on the map before a silent, sceptical audience.

Before, Lynch had rebuffed Ernie O’Malley’s attempts to reorganise the IRA positions in Dublin on more defensible lines. The ongoing talks would resolve the tensions, he assured the other man. Precautions in case of failure were unnecessary because failure was not going to happen.[25]

Events had cruelly exposed the pitfalls of such myopic thinking, yet Lynch had learnt nothing and, as the war progressed and the situation tightened like a noose, he would be even less inclined to do so.

To be continued: The Self-Deceit of Honour: Liam Lynch and the Civil War, 1922 (Part IV)

References

[1] Free State, 08/07/1922

[2] Cork Examiner, 12/07/1922

[3] Deasy, Liam, Brother Against Brother (Cork: Mercier Press, 1998), p. 48

[4] O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), p. 124

[5] Andrews, C.S., Dublin Made Me (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001), p. 247

[6] Deasy, p. 73

[7] Ibid, pp. 48-9 ; Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Fontana/Collins, 1970), p. 336

[8] Deasy, pp. 49-51

[9] O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin: Irish Press Ltd., 1954), p. 259

[10] Younger, p. 337

[11] Blythe, Ernest (BMH / WS 939), pp. 142-3 ; Irish Times, 05/05/1922

[12] Cork Examiner, 14/07/1922

[13] Ibid, 01/07/1922

[14] MacEoin, Uinseann. Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), p. 25

[15] Ibid, p. 269

[16] Ibid, pp. 98-9

[17] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), pp. 78-80

[18] Brennan, Robert (BMH / WS 779), Part III, pp. 191-2, 194-7

[19] O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007), p. 51

[20] Brennan, p. 197

[21] Liam Lynch Papers, National Library of Ireland, MS 36,251/24

[22] Irish Times, 24/07/1922

[23] O’Donoghue, p. 184

[24] Andrews, p. 268

[25] O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012), pp. 100-2

Bibliography

Books

Andrews, C.S. Dublin Made Me (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001)

Deasy, Liam. Brother Against Brother (Cork: Mercier Press, 1998)

MacEoin, Uinseann. Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin: Irish Press Ltd., 1954)

O’Malley, Ernie (edited by O’Malley, Cormac K.H. and Dolan, Anne, introduction by Lee, J.J.) ‘No Surrender Here!’ The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, 1922-1924 (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2007)

O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

O’Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame (Cork: Mercier Press, 2012)

Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Fontana/Collins, 1970)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Blythe, Ernest, WS 939

Brennan, Robert, WS 779

Robinson, Séumas, WS 1721

Newspapers

Cork Examiner

Free State

National Library of Ireland Collection

Liam Lynch Papers