War and Peace?

While not exactly unwelcome, the Armistice on the 11th November 1918, that finally put an end to four years of war, complicated an already tense situation in Ireland. “The defeat of the German Army which they believed to be impossible was an embarrassing surprise” for Sinn Féin, wrote Sir Joseph Byrne, the Inspector-General of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in his monthly report to Dublin Castle. Such feelings could go beyond mere awkwardness. According to Ernest Blythe, then a political prisoner in Dundalk Jail, so convinced were many of his fellow Sinn Féiners of a German win that the news to the contrary plunged them into a state of gloom.[1]

All of which was less to do with a desire for a German win and more for a British loss. But what really rubbed Sinn Féin activists like Liam de Róiste and Kevin O’Shiel the wrong way was having to watch some of their fellow countrymen revel in the victory. “Soldiers and their ‘women’ paraded [through] some of our [Cork] city streets last night, jeering, shouting, ‘singing’,” wrote the former in his diary on the 12th. Still, after a few scuffles and a baton-charge by the RIC, “things passed more quietly than might have been expected, with the flush of victory strong in the blood of the pro-English.” O’Shiel was similarly aggrieved at the sights and sounds of the “rejoicing pro-British crowds” and “Rathmines Jingoes” as they marched through Dublin, waving Union Jacks and singing wartime songs such as It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.[2]

Unlike Cork, things in Dublin did not pass quite so quietly. By coincidence, Sinn Féin was having a big event of its own that evening, at the Mansion House, presided over by Alderman Thomas Kelly. The agenda was originally intended to be the start of the party’s campaign for the forthcoming general election, Kelly told the packed hall, but, given the news of the day, something more was now to be announced: the declaration of Ireland’s independence as a separate and distinct nation.

So full was the venue that some of the attendees had to stand outside in the street, where they passed the time by singing The Soldier’s Song and other rebel tunes in vogue. This caught the notice of travellers on the passing trams, who either waved Union Jacks and Stars-and-Stripes in provocation or shouted ‘Up the Rebels’ and ‘Up de Valera’ in support. After two hours of this, the crowd, numbering in the hundreds, decided to take a more proactive approach and marched in processional order, still singing, away from the Mansion House, over O’Connell Bridge and into Sackville (now O’Connell) Street.

“The crowd through which they passed was thoroughly good-humoured,” reported the Irish Times, “and no collision occurred.” The only flickers of trouble was when a British officer grabbed the tricoloured flag at the head of the procession, leading to a fracas on the corner of Grafton Street and, later, when the marchers attempted to return by Westmoreland Street, only to be blocked by police. Instead of pressing ahead, the Sinn Féiners dispersed. Similarly civilised was when the meeting at the Mansion House drew to a close and those inside departed, “singing and cheering, along the same route, but no untoward incident occurred.”[3]

The Order of the Day

Given the tempers of the time, this ‘live and let live’ attitude could not last long. On the following evening, as the celebrations continued in Dublin, incidents of a more serious nature were reported in different parts of the city centre, as Sinn Féiners clashed with British soldiers, prompting on one such occasion a police charge in Grafton Street (among the injuries of the day was a constable struck on the head with a bottle). But it was the day after that, on the 13th November, that the city practically became a warzone.[4]

“The streets of Dublin were almost in their normal state yesterday,” reported the Irish Times on the 14th, “but after nightfall crowds assembled in the principal thoroughfares, though not on a scale approaching the dimensions of the gatherings of the two previous nights.”[5]

Smaller, perhaps, but no less volatile. By the end of the night, no less than four places in particular had borne the brunt of the crowd’s wrath:

- The Mansion House, Dawson Street.

- Sinn Féin headquarters, 6 Harcourt Street.

- Liberty Hall, Beresford place, headquarters of the Transport Workers’ Union.

- Emmet Hall, Inchicore, meeting place of the Irish Transport Union.

That each were associated in some way, either with Sinn Féin in particular or, in the case of the last two, the current rise in radicalism, makes it hard to believe that their targeting was by chance or a coincidence. “I was sitting in my study about 7:45 [pm],” Laurence O’Neill, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, told the press later about the assault on the Mansion House:

Looking out, I noticed a __ __ __, numbering two or three hundred, waving sticks and Union Jacks, and making use of language certainly not very polite towards me.

Rough speech was soon to be the least of the Lord Mayor’s concerns:

Some came to the door and made use of hatchets, with the object of forcing it in. They broke the windows with stones and used sticks to break the lamps outside. Things looked very dangerous, when a bluejacket got on the steps and exhorted the crowd to move off.

After one final indignity, an attempt to set fire to the door of the Mansion House that mercifully fizzled out, the mob did indeed move off, singing, according to O’Neill, God Save the King as they did so.

Emmet Hall in Inchicore had it the easiest that night, ‘only’ enduring stones thrown at it by soldiers who otherwise did not approach the building, and even then the fusillade lasted for no more than six minutes. Over at Liberty Hall, clerks and union officials huddled inside as a crowd consisting of “noisy young soldiers, accompanied by sailors, members of the WAAC [Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps], and several males and female civilians” smashed the lower windows and the glass panes in the door with sticks and trench tools. When the sounds of several gunshots were heard, seemingly from the roof of the building, the assailants decided they had had their fun and hastily scattered.

As for the Sinn Féin offices on Harcourt Street, they “presented a strange appearance” the following morning, almost every window being broken and an iron railing left lying by the front entrance. But visiting journalists found the party officials, far from being downcast or defeated, in a jubilant mood over how they had heroically held their own:

At about 7:40, practically the same hour as the raid on the Mansion House, a crowd of soldiers and civilians…proceeded to attack the headquarters of the Sinn Fein Organisation. There were about 30 Sinn Feiners inside the premises…The defenders with sticks and bare knuckles beat back the attackers, and although the latter reached the steps of the house, they never succeeded in gaining an entrance.[6]

“This was primitive warfare at its best,” recalled Simon Donnelly with some gusto. Stones through the window had alerted him and the other Irish Volunteers stationed inside to the onset of the anticipated attack. At a given signal, other Volunteers, waiting on standby outside, rushed into the fray and soon “skull-cracking was the order of the day” on the street. One combatant in particular made an impression on Donnelly: Harry Boland, “a man of fine physique” who “did trogan [sic – Trojan] work, as everytime he hit an enemy went down.” Soon the battle of Harcourt Street was done and won, and “the mob eventually retired, sadder but wiser people.”[7]

Perhaps de Róiste summed it up best. “True, peace is in being,” he wrote in his diary. “But an armistice is only a temporary cessation of hostilities” – at least, where Ireland was concerned.[8]

Intemperate Language

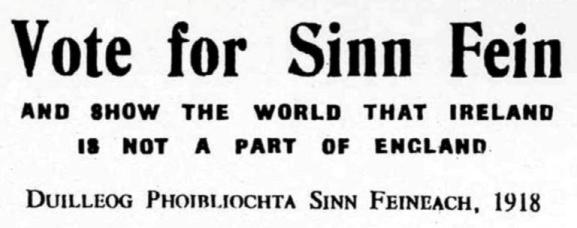

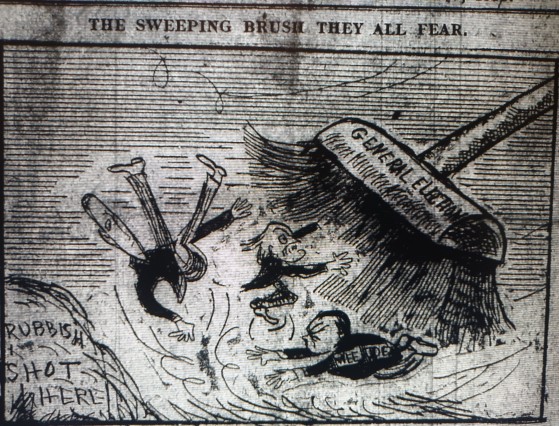

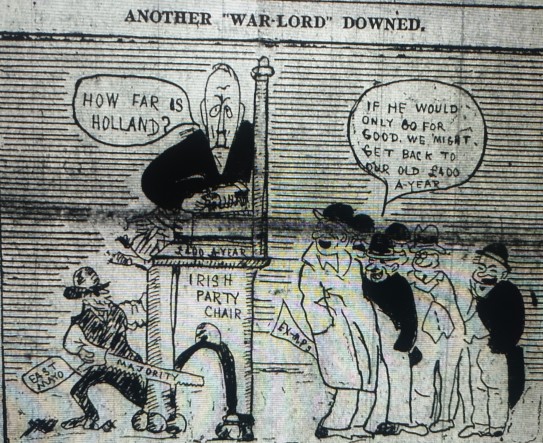

Amidst this turmoil was the General Election to be conducted the following month, in December. The only certainty, it seemed, was that Sinn Féin would win and the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) was on its way out. When reviewing the month of November for Dublin Castle, Sir Joseph Byrne gave the IPP only a single paragraph. It was all the former party of Parnell and Redmond, and the standard-bearer for Irish national aspiration for decades, warranted, it seemed.

“For some time past it has been obvious that the Irish Parliamentary Party had outlived her popularity, even with the R.C. [Roman Catholic] clergy,” the RIC Inspector-General noted:

The chief complaint now urged against them is that they failed to obtain from Government satisfactory guarantees with regards to Home Rule. Their organization has been similarly apathetic with regard to the new register of voters. Thirty-two members of the Party did not seek re-election, allowing twenty-five Sinn Feiners to be elected on nomination day unopposed, and it is not improbable that many more Nationalist seats will be lost.

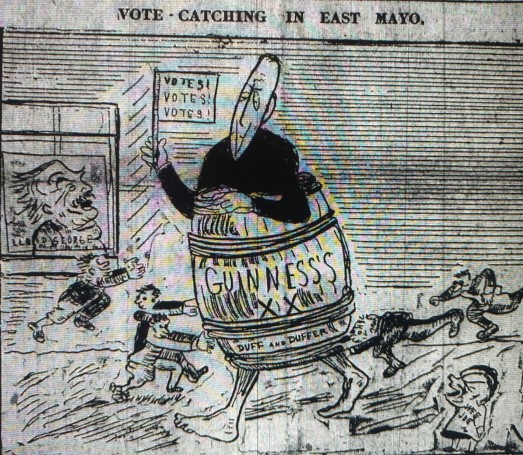

Against such a backdrop, it is unsurprising that Sinn Féin would merit far more attention in Byrne’s report. In contrast to the flaccid defeatism of the IPP, “the Sinn Fein party was most active and nominated candidates for 102 of the total 105 constituencies.” Despite this, public meetings for the party remained small and “none of them could be described as enthusiastic,” which the Inspector-General attributed to the mass arrest of its leadership, including its president Éamon de Valera, who were now sitting behind prison bars for their supposed role in the so-called ‘German Plot’ earlier in the year, in May 1918.

Not that the absence of its head had tamed the Sinn Féin body, whose speakers at meetings “made the usual demand for separation from England and complete independence,” but “making allowance for the heated atmosphere of an election contest the language used, though disloyal and bitterly anti-English, was, on the whole, not worse than might be anticipated.” Still, what was being said was ‘disloyal’ enough, particularly for the party’s clerical supporters, who “were more intemperate in their language than the lay men.”

An example of the kind of speech being typically used at Sinn Féin rallies, and from two men of the cloth no less, was at Kilfinane, Co. Limerick, on the 24th November 1918. There, the Rev. Father Hayes read out the oath of allegiance taken by Members of Parliament (MPs), and then asked how any man could take that oath and be faithful to Ireland. Any and all past concessions had not been earned by sending men to Westminster, quite the contrary in fact: Catholic emancipation was won by British fear of Irish rebellion, Church of Ireland disestablishment by the sacrifice of Fenians, and land acts by farmers barricading their houses.

Next to speak was the Rev. Father Wall. The policy of Sinn Féin, he told his audience, was that of Ireland as a nation:

In the course of his speech he said that they had more than one string to their bow. They did not depend entirely on the [post-war] Peace Conference. Sinn Féin would establish a constituent assembly which would use moral force, and perhaps other force, in furtherance of the cause of their country, and that later they would if necessary use physical force. He added that they intended to send envoys to the United States and other countries to stir up enmity against England.

Not everyone in Sinn Féin was quite so committed, at least according to one police informant who had spent time in the Dublin offices on Harcourt Street. “Most of the extremists do not expect a republic and would be satisfied with colonial home rule,” this anonymous source told their handlers – that is, if it was Sinn Féin who could claim responsibility.

Otherwise, what the spy reported chimed in with what Father Wall said at Kilfinane: that Sinn Féin (1) was willing to set up for Ireland a parliament of its own, “a constitutional assembly to replace British rule”, (2) was looking overseas for support, particularly at the Peace Conference, “to lay out the Sinn Fein cause before the nations”, (3) had a willingness to employ violence for its ends due to “an extreme section which in time of excitement might plunge the country into serious trouble.”

‘This Branch of Sinn Féin’

Sinn Féin was indeed a broad church or, as Father Wall had put it, a string with many bows. Making up its prospective candidates for the election were a mix of doctors, solicitors, farmers, shopkeepers, clerks, students and even a humble labourer, their only requirement being “rebel antecedents” as none had ever sat in Parliament before, a far cry from the decades of service many of the MPs in the IPP could point to.

Less easy for the RIC to evaluate were the Irish Volunteers as, since the recent ban on political gatherings without a permit and a general clampdown on the part of the authorities, “the Irish Volunteers have become practically a Secret Society.” Information on that paramilitary body was thus hard to come by, save from documents found on suspects or in their homes during searches; even the source of their newspaper, An tÓglach (spelt ‘An Toglach’ in Byrne’s report) was largely unknown.

Still, the RIC had observed enough about the Volunteers to know that they and Sinn Féin were very much joined at the hip. An example of this alliance was how the number of companies nearly corresponds to the number of Sinn Fein clubs reported by the police.” Elsewhere in his summary, the Inspector-General referred to the Volunteers as “this branch of Sinn Fein” as if they were one and the same, which was not, strictly speaking, true, but also not entirely inaccurate at the same time.

A more pressing question for Dublin Castle about the Volunteers was their capacity for another uprising. For this, Byrne presented a mixed picture. At first glance, the Volunteers did not appear to be a great threat, being insufficiently armed and equipped for conflict with soldiers, and fear of the troops restrains them from rebellion.”

In the long run, however:

Unless a counter movement of the responsible citizens should arise, of which at present there is no indication, [the Volunteers] are sufficiently organized with the weapons at their disposal, and supported in every direction by numbers of turbulent young men who if not actually in thier [sic] ranks are in close sympathy with them, to be unmanageable and to make government impossible in the event of the Military Force in the country being reduced.

Sinn Féin likewise looked immune to the apprehension of ‘responsible citizens’ and other respectable types, being “too strong to be affected by adverse opinions or warnings from any quarter” come polling day. And if the Irish Volunteers could indeed make Ireland ungovernable for Britain, then their political partner was already “keeping the whole country in a state of unrest by its republican pretensions.”[9]

Plenty of Punch

Which is not to say Sinn Féin was having everything its own way, nor that the IPP had completely given up the will to live. The former, to quote O’Shiel:

…fought the General Election of 1918 under very great handicaps. Most of its leaders and, indeed, its candidates, were imprisoned or interned, most of its newspapers and journals were suppressed and what was permitted of them so severely censored that they were of little propaganda value.[10]

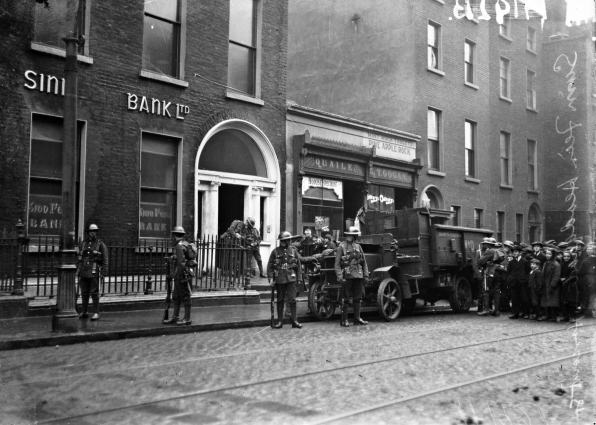

Sinn Féin was forced accordingly to rely on whoever it had on hand for help. P.S. O’Hegarty walked in on Harry Boland in their Harcourt Street offices reading through a list of names and picking who was to stand and who would not, a slightly disconcerting sight which O’Hegarty found to be “an illuminating insight into democracy” (‘skull-cracking’ being only one of Boland’s many duties). Compounding the difficulties was the arrest of Robert Brennan on the 20th November 1918 at the Sinn Féin headquarters, the fourth such raid on the premises in the past six months. Given the thirty armed policemen and half a dozen detectives in attendance, the authorities were clearly taking no chances and Brennan was driven away in a military motor van, along with six hundred confiscated copies of the party manifesto.[11]

That made him the third Director of Elections for Sinn Féin to be so removed (his predecessors, Seán Milroy and Dan MacCarthy, having both been deported earlier that year). Luckily, Brennan had had the foresight to leave for party workers like Máire Comerford:

…very precise instructions as to our duties before and during the campaign. These were observed in scrupulous detail. With patience and devotion we copied every name on the [electoral] register into three different notebooks for each townland in every constituency. The attitude of voters, after each of the three canvasses, was recorded and sent to the constituency director. Absolutely no effort was spared to win the contest.

After all, more than an election hung in the balance as far as Comerford was concerned: “The responsibility to vindicate the men of Easter Week was on our shoulders.[12]

Even if the Irish Party could not match that sort of crusading zeal, it was to display a dogged, never-say-never determination of its own. Many had been writing it off as early as 1917, when the first of its by-election defeats began, yet still the IPP struggled on, making its would-be successor fight for every inch of political ground, sometimes in more than a figurative sense. “The Redmondites in the city had plenty of punch, and I mean punch, in that election,” Frank Edwards said wryly of Waterford. He was referring to the by-election earlier in 1918, one of the few wins the IPP could claim and which, for a time, looked set to reverse the tide back in its favour.[13]

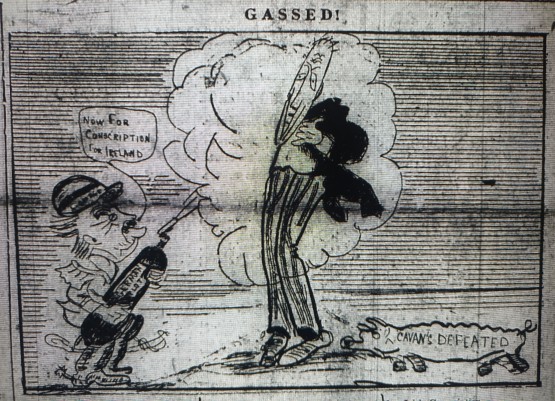

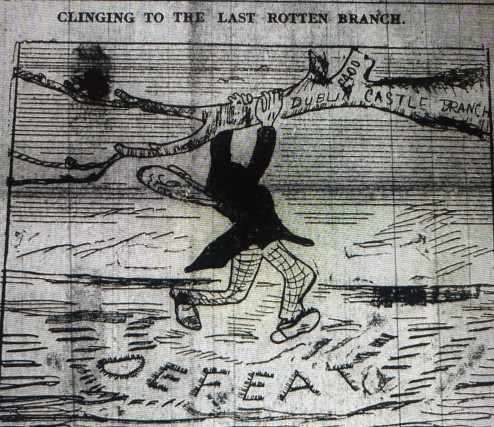

That hope soon dissipated, yet, even so, Dillon refused to give up, being, in the words of one biographer, “a man fully committed to what he knew to be a mortal combat, and watching every move and sign of the enemy to snatch what advantage he might from a desperate situation.” If victory was no longer plausible, then a rear-guard action would have to do. “It is quite conceivable that in six months,” the IPP Chairman told T.P. O’Connor in June 1918, “Ireland may have sobered down so much that we shall emerge from [the general] election with say 40 seats.” But this was before the results of the East Cavan by-election were in; when they were, and it was known that Sinn Féin had triumphed by over a thousand votes, forty seats suddenly seemed less than attainable.[14]

Disappearing to Reappear?

Some long-time allies were wanting the Irish Party to quit altogether: John Horgan in Cork City proposed in October that its MPs withdraw from Parliament to better present a united front with Sinn Féin together at the Peace Conference, while Dr Patrick O’Donnell, the Bishop of Raphoe, similarly urged the IPP to stand down its candidates for the general election that month, to “disappear to reappear”, as His Eminence put it. Dillon firmly declined both suggestions, taking the time to explain to each man in detail his reasons why.

Abandoning Westminster would hand the Irish pulpit entirely to the Unionists, he told Horgan, an act which “is to me an absolutely insane one.” As for the Peace Conference, “there is not the slightest chance of representatives of Ireland being allowed to enter such” an event and, even if they were, the Irish envoys would receive a reception “of a very painful, and to them, surprising character,” thanks to Sinn Féin’s unsubtle favouritism towards Germany – the wrong horse, it turned out, to have backed.

Regarding Dr O’Donnell, Dillon had given his advice “the most careful consideration,” he assured the Bishop. But:

You speak of ‘disappearing to reappear’ – could a political leader guilty of such conduct ever reappear, or show his face, in public life? Could he reasonably expect the people to trust him or place any reliance on what he said?

Clearly not, in Dillon’s opinion:

If there is one thing more than another which the Irish people cannot tolerate in a political leader it is cowardice, and failure to stand and fight for the principles which he says he believes in. And in this I must say I heartily agree with the people.[15]

With that said, there was nothing left for the IPP Chairman to do but gird his loins in defence of the East Mayo seat he had held for thirty years. Not all his colleagues were joining him: as noted in the RIC report for November, some constituencies were being left wide open for Sinn Féin to claim as their previous MPs stood down in the face of almost certain electoral annihilation.

In South Meath, for example, David Sheehy seems to have decided that three general elections were enough for one career and that a younger candidate should to try his luck. Lorcan Sherlock was asked by telegram to stand instead for the IPP, despite his current duties as City Sheriff in Dublin, a place he had far more connection with as a former lord mayor than he did with Meath; besides, Sherlock had not been notified in advance and so unsurprisingly turned the invite down. It was not much of an offer anyway. So desperate by then were the IPP supporters in South Meath for someone that they resorted to asking Dillon to provide a name.

The one they eventually got, Thomas Peter O’Donoghue, also lacked a background in the constituency, being a Kerryman, and while he proved an active enough campaigner in the short amount of time left, the contrast with the Sinn Féin campaign, which selected its candidate, Eamon Duggan, early on and began canvassing at once, could not have been starker.[16]

In the years to come, Monsignor M. Curran, secretary to the Archbishop of Dublin and a keen political observer, would read the obituaries of former Irish Party stalwarts and remark along the lines of ‘I thought that man was dead long ago.’ David Sheehy exemplified that decline into shabby obscurity, living with a daughter who, as his wits wandered in his old age, “was inclined to bully him,” remembered his grandson, Conor Cruise O’Brien (who was to walk a political path of his own). “Was she unconsciously punishing him for having lost his parliamentary seat in 1918, and for our dynasty’s decline?”[17]

‘Not as Rebels, but as Insurrectionists’

Those still standing worked hard at giving as good as they got. In South Roscommon, John Patrick Hayden dismissed his rival, the ubiquitous Harry Boland, as “only a tramp tailor”, the Sinn Féin policy of an Irish Republic as “impossible to realise, unless it could be enforced by an army and navy equal to that of Great Britain,” and the other main Sinn Féin platform, that of abstentionism, in a tone of incredulity: “How were social reforms to be won? How were Irish interests to be safeguarded?”

As Hayden was the proprietor of a local newspaper, he could at least expect a certain amount of good coverage. One poem submitted to the Roscommon Messenger just happened to chime with Hayden’s stated sentiments – assuming, that is, Hayden was not its author:

I would ask you, Mr Boland, will you stay

From attending to our business in the Commons o’er the way?

Where our taxes will be trebled by Lloyd George and Bonar Law,

Who, for all your bogus risings, do not give a single straw.

“Friend,” he says. “the House of Commons is no fitting place for me,

I’m too advanced a rebel for that quarter, don’t you see;

But to South Roscommon’s business I’ll attend without a stint,

When we form our new Republic and our Irish Parliament.

Boland, for his part, generally avoided that type of personal attack, preferring – for the most part, anyway – to argue in favour of his cause rather than against the opposition’s. “We are not looking for prolonged power,” he told a Sinn Féin rally in Roscommon town on the 24th November 1918. “We believe in new times, new men and new ideas.” He did not so much counter Hayden’s accusation of abstentionism leaving Ireland open to taxation as dismiss its importance altogether: “I do not like to discuss these questions from a material point of view. I, for one, would rather see Ireland with a crust in her mouth standing erect, proud and free, than fat and sleek and prosperous, a beggar and a slave” – which, judging from the resulting cheers, shows Boland had read his audience well.

During the Rising, he and his comrades had gone out “not as rebels, but as Insurrectionists, for we spoke for a Nation”; he contrasted them with those Irishmen who had fought in the Great War “now lying in unhallowed graves in France and Flanders and every other battle front.” Boland could not resist another dig, this time at the IPP’s expense: “The Party complained that the people had deserted them. Well, no; the Party had deserted Ireland and the people had remained true.”

As with many Irish elections of this period, the exchanges could go beyond the verbal. IPP partisans tore down republican tricolours at one booth in Castlerea on polling day, the 14th December, and stamped on them until driven off by Irish Volunteers; more Volunteers, armed with hurleys and ashplants, surrounded the polling booths in Roscommon town and had to be dispersed by the returning officer. Despite the RIC Inspector-General’s description of them as a ‘secret society’, the Volunteers remained a visible presence throughout the country, to the point of escorting the ballot boxes being taken to the Roscommon courthouse for counting in blatant defiance of the RIC constables on duty.

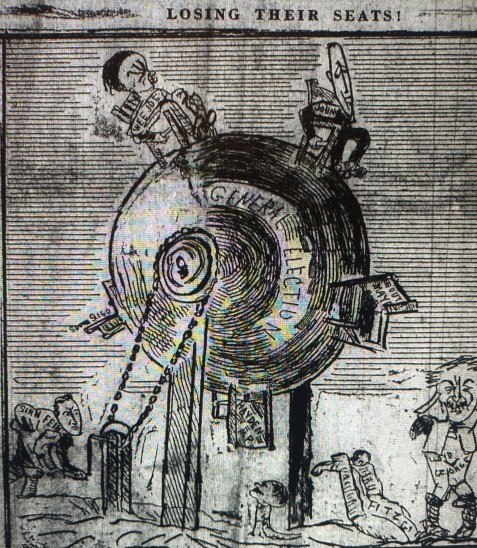

Boland later emerged from that same courthouse to be carried shoulder-high to his party’s headquarters in town, where speeches, bands, a torchlight procession and house illuminations marked his electoral triumph – a mighty 10,685 votes to Hayden’s pittance of 4,233. It was but one victory among many.[18]

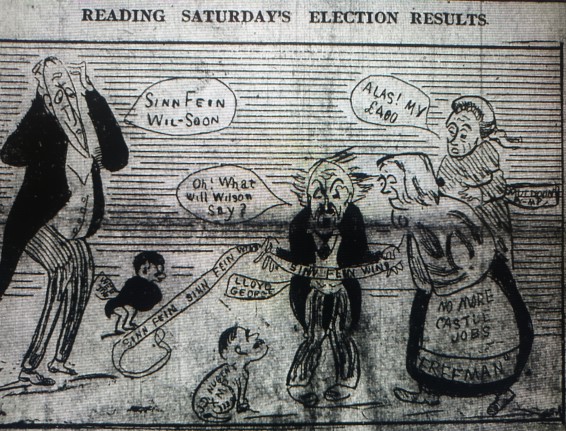

Landslide

Dillon had been bracing himself for the worst; even so, “the landslide is a good deal greater than I had expected from my reports, and I confess some of the results have surprised me very much,” he wrote to T.P. O’Connor in December after the votes had been tallied.

Actually, it was an impossibility and everyone but Dillon knew it. “We finished Redmond and everything he stood for, and whatever the future may hold for Ireland, Republicanism will always hold sway here,” wrote Nora Connolly, daughter of the 1916 martyr. She was writing sometime after, but one does not have to look very far for contemporary reports on the finality of the result. “The defeat of the Nationalist Party is crushing and final,” intoned the Irish Times, as little as that most conservative of newspapers must have liked it. “Sinn Féin has swept the board, but we do not know – does itself know? – what it intends to do with its victory.”[20]

Good questions: no less a prominent figure in the newly ascendant power than Father Michael O’Flanagan, one of its two vice-presidents, was heard to say that, since the people had voted Sinn Féin, “what we have to do now is to explain to them what Sinn Féin is.”[21]

In other words: what next?

References

[1] Police reports from Dublin Castle records (National Library of Ireland – NLI), POS 8547 ; Blythe, Ernest (BMH / WS 939), p. 98

[2] ‘25 October – 17 November 1918’, Liam de Róiste Diaries Online, Cork City Council (Accessed on 15/05/2023), p. 71 ; O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770, Part 6), p. 41

[3] Irish Times, 12/11/1918

[4] Ibid, 13/11/1918

[5] Ibid, 14/11/1918

[6] Evening Herald, 14/11/1918

[7] Donnelly, Simon (BMH / WS 481), p. 11

[8] De Róiste, p. 71

[9] NLI, POS 8547

[10] O’Shiel, p. 45

[11] O’Hegarty, P. S. The Victory of Sinn Féin (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2010), p. 53 ; Evening Herald, 20/11/1018

[12] Comerford, Máire (ed. by Dully, Hilary) On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2021), p. 94

[13] MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), p. 2

[14] Lyons, F.S.L. John Dillon: A Biography (Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., 1968), pp. 440-1

[15] Ibid, pp. 446-8, 450

[16] Bruton, John. ‘The 1918 Election and its Relevance to Modern Irish Politics’, An Irish Quarterly Review (Spring 2019, Volume 108, No. 429), pp. 94-5

[17] Curran, M. (BMH / WS 687, Section 1), p. 345 ; O’Brien, Conor Cruise. States of Ireland (London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974), p. 104

[18] Fitzpatrick, David. Harry Boland’s Irish Revolution (Cork: Cork University Press, 2003), pp. 110-2

[19] Lyons, pp. 453-4

[20] MacEoin, p. 209 ; Irish Times, 30/12/1918

[21] O’Hegarty, p. 21

Bibliography

Newspapers

Evening Herald

Irish Times

Roscommon Herald (cartoons)

Books

Comerford, Máire (ed. by Dully, Hilary) On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2021)

Fitzpatrick, David. Harry Boland’s Irish Revolution (Cork: Cork University Press, 2003)

Lyons, F.S.L. John Dillon: A Biography (Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., 1968)

MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

O’Brien, Conor Cruise. States of Ireland (London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1974)

O’Hegarty, P.S. The Victory of Sinn Féin (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2010)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Blythe, Ernest, WS 939

Curran, M., WS 687

Donnelly, Simon, WS 481

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

National Library of Ireland Collections

Police Report from Dublin Castle Records

Online Source

Liam de Róiste Diaries

Article

Bruton, John. ‘The 1918 Election and its Relevance to Modern Irish Politics’, An Irish Quarterly Review (Spring 2019, Volume 108, No. 429)

excellent, well-researched review of the 1918 election and the fall of the IPP

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent piece, I really enjoyed reading it

LikeLiked by 1 person