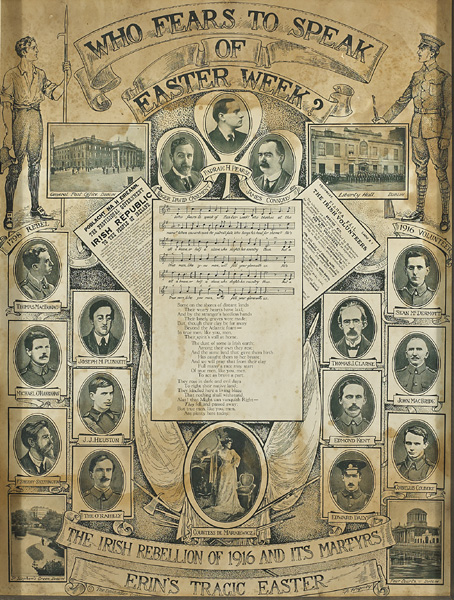

The Full Story?

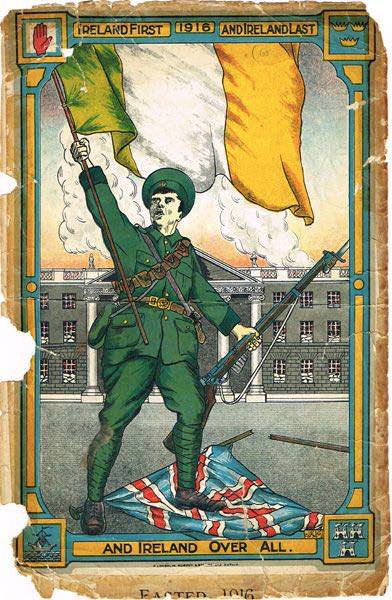

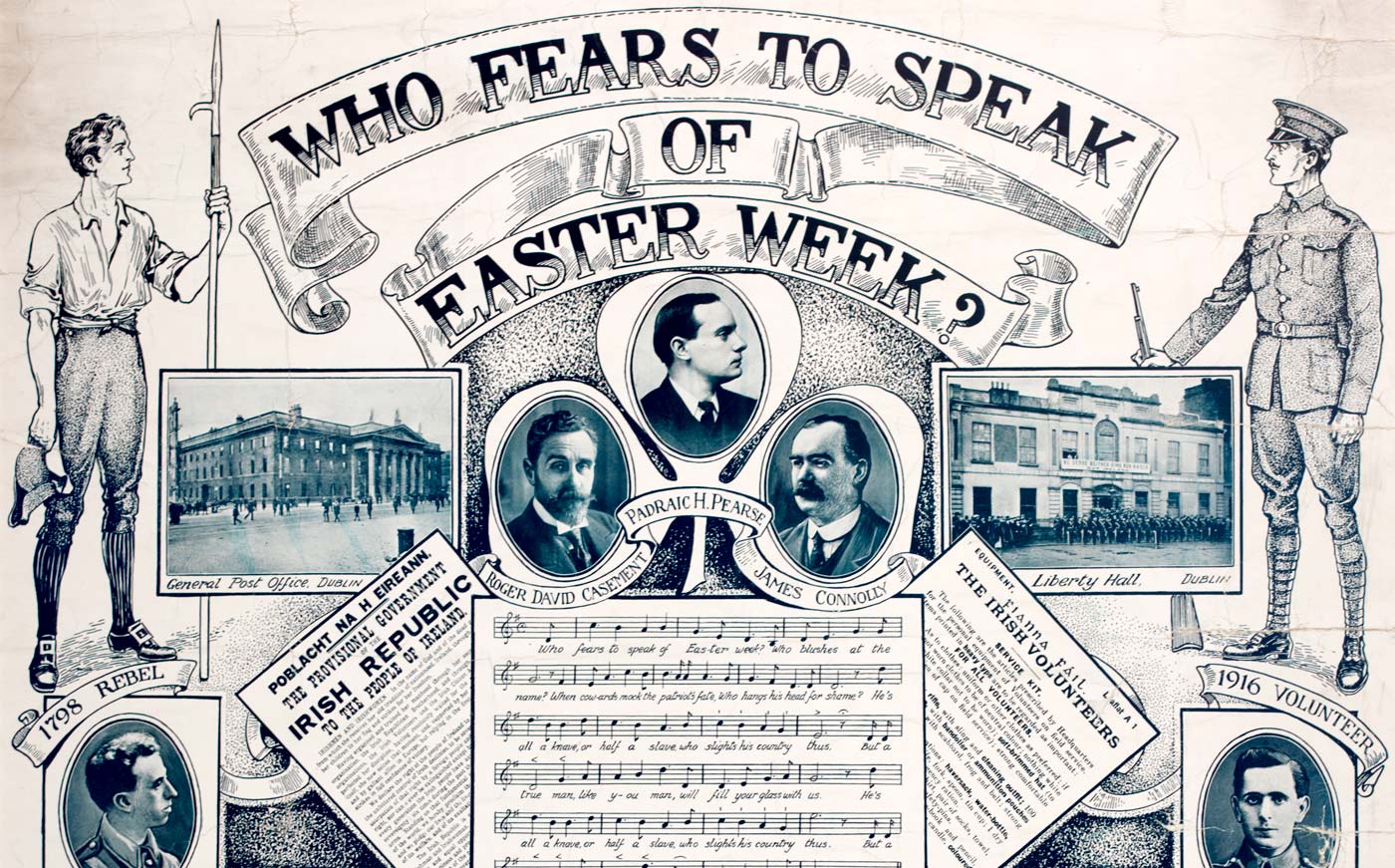

When Seán Doyle donated some items concerning the Easter Rising to the National Museum, he did so, as he explained in a letter, because he felt that “the interesting part played by Wexford has been not hitherto adequately represented.” He was writing in 1934 and it seems that his efforts made little headway as, eighty-one years later, another Doyle thought it necessary to offer “a gentle rebuke” to those historians “who promote the view that the 1916 Rising was confined to Dublin” at the expense of Co. Wexford and the overlooked “significant event” of its own during that momentous week.[1]

‘Significant’ may be too strong a word. Nonetheless, while it is true that the county had nothing compared to the slaughter on Mount Street, the naval bombardment from the Liffey or the final holdout in the General Post Office (GPO), it does provide an alternative version of the Rising, or how Easter Week could have gone.

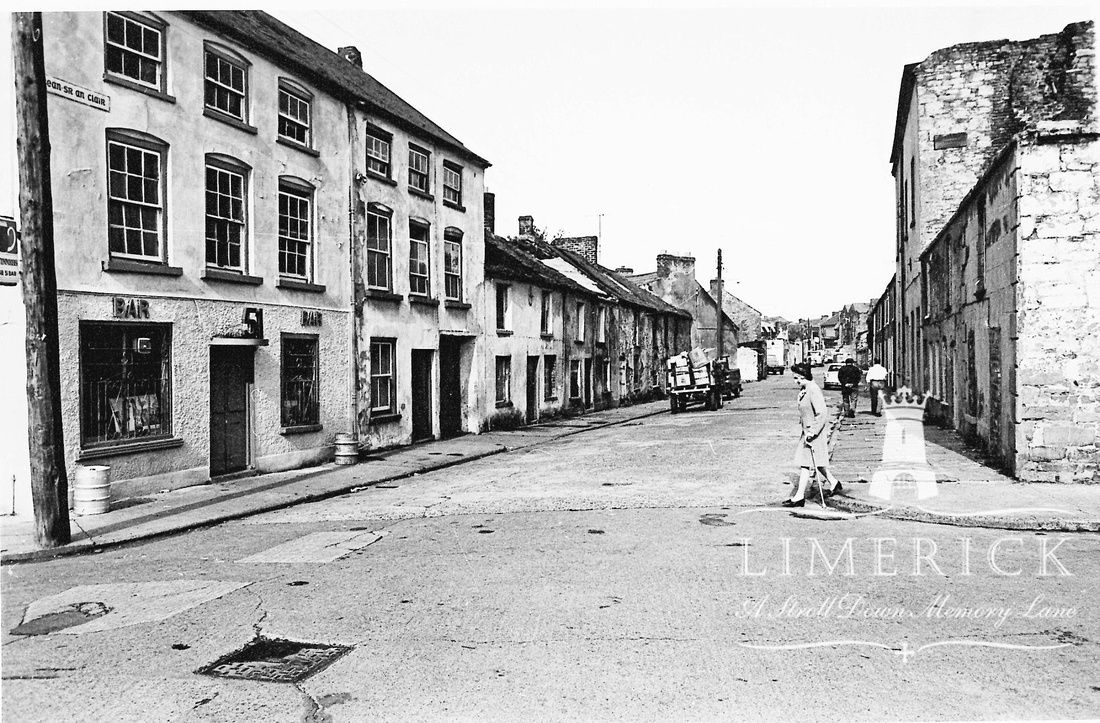

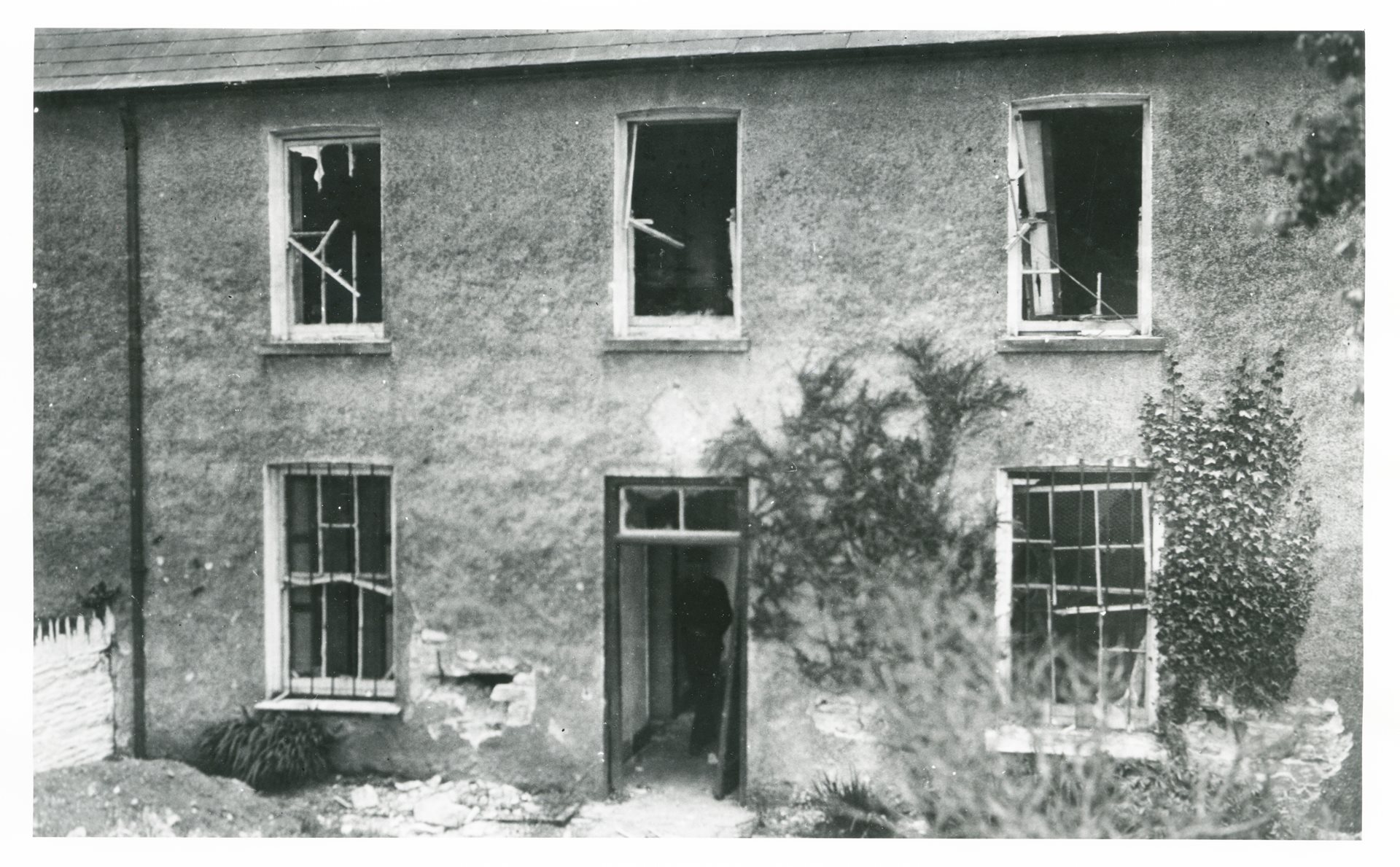

Certainly, at least one journalist, writing in the Irish Times at the end of April 1916, barely before the dust had settled and the embers cooled, believed that “when the full story of the rising at Enniscorthy comes to be written it will provide one of the most interesting chapters of the ill-fated rebellion of the Sinn Feiners.” While information was sketchy, it appeared that, at the start of Easter Week, the Irish Volunteers involved had not acted immediately, instead waiting for news of their compatriots in Dublin. When it was confirmed that the city was in rebel hands, the Wexford men swung into action, first seizing the business establishments of Enniscorthy, along with its railway station.

Whether to blow up the town bridge was debated but declined. Instead:

They then attempted to blow up the bridge at Scarawalsh, which crosses the River Slaney on the main road between Wexford and Enniscorthy. Before doing so they behaved with cruelty to the old and respected blacksmith, named Carton, who, with his family, live in a house close to the bridge. Carton and his family were ordered to leave the house, and had to wander about homeless for two days and two nights.

The Cartons were not the only ones inconvenienced. Factory workers on the train out of Wexford had been held up at Enniscorthy Station and forced to walk back along the railway line. And a class war seemed to have been waged as well as a national one: “While the revolution lasted employers were held up by their own workpeople.” Such societal reversals was something that the Men of Property, in the aftermath, were taking rather personally:

The greatest indignation prevails amongst the business people of the town and district, and the hope is expressed on all sides that the rebels will be hunted out to a man…There is a general feeling that, if the spirit of revolution is not ruthlessly stamped out, the trade and business of Enniscorthy will be ruined.

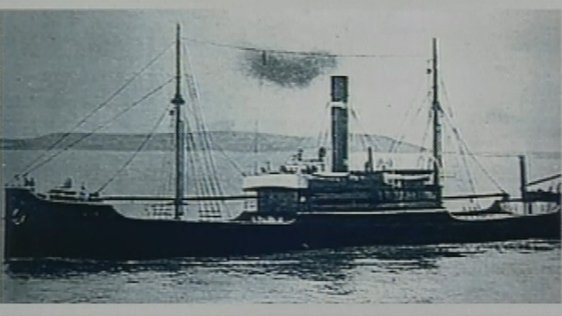

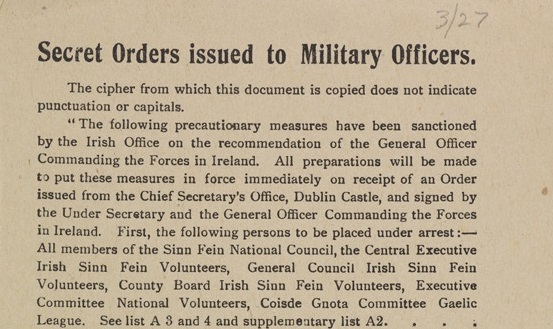

For a failure the Rising had been, in Enniscorthy and elsewhere in the country, and it was the Volunteers who were now at the mercy of others. One hundred and thirty-three suspects had already been rounded up by the authorities in Co. Wexford alone, with more to come. That these prisoners were being sent abroad by steamer to an unknown destination showed how seriously the Powers-That-Be took this latest threat.[2]

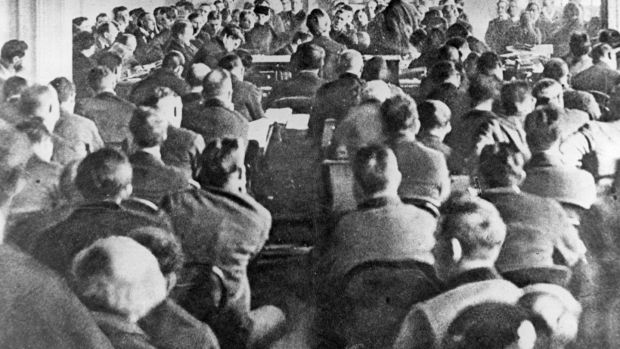

By the time the Royal Commission met a month later, on the 27th May 1916, at the Shelbourne Hotel in Dublin, to investigate the recent rebellion, three hundred and seventy-five altogether had been arrested in Co. Wexford. Out of these, three hundred and nineteen were transported to Dublin for later deportation, with fifty-two discharged and a pair taken to hospital. The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), meanwhile, had seized a total of:

- 45 rifles

- 66 shotguns

- 8 pistols

- 6 revolvers

- 1 bomb

- 21 ½ stone of blasting powder

- 667 rounds of sporting ammunition

- 4,067 rounds of rifle and revolver ammunition

- A quantity of gelignite and other explosives

“A regular arsenal,” exclaimed Lord Hardinge as Chairman.[3]

Laying the Plans

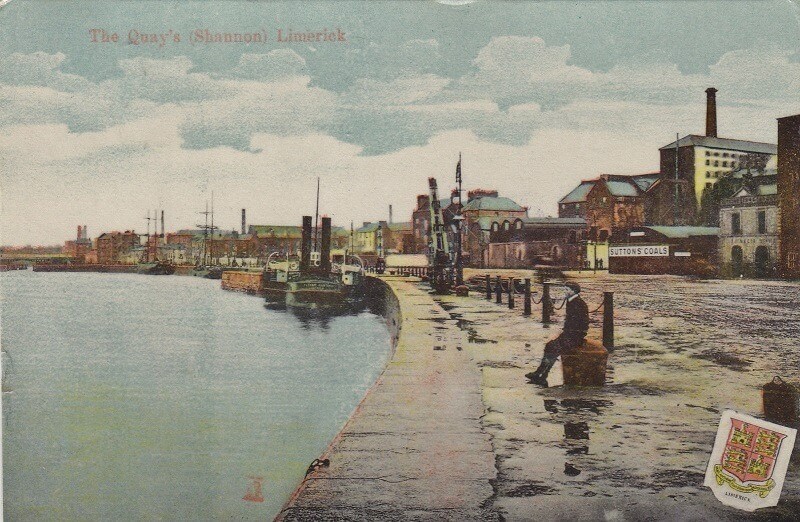

As Lord Hardinge grasped, the Volunteers in Wexford had been in complete earnest. So was the rebel leadership, which had had big plans for them. Given its position on the south-west coast of Ireland, the county was to serve two important tasks in the course of the Rising. Firstly, as explained by W.J. Brennan-Whitmore, they were to keep the line of communications open between the Irish Volunteer GHQ in Dublin and their units all the way to Cork. The second was more complicated, concerning Waterford city, “the really black spot” in Brennan-Whitmore’s (and the GHQ’s) view and a potential Achilles’ heel for their insurrection.

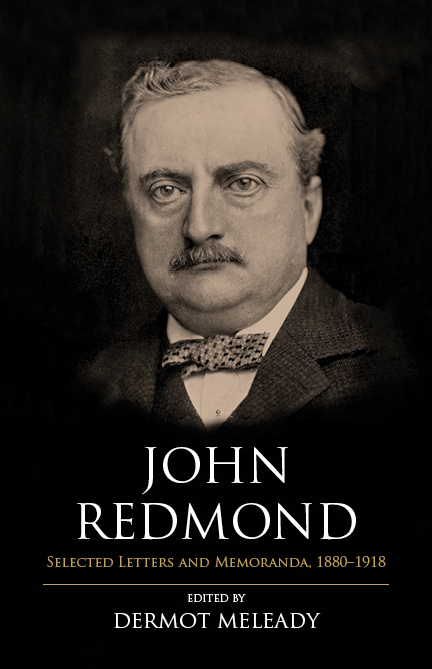

With its harbour, Waterford provided a natural entry point into Ireland, from which disembarking enemy reinforcements could quickly penetrate into the heartlands. Seizing the city outright did not seem feasible, considering the pro-Redmondite and anti-Republican sentiments there, so the next best counter-measure would be one of containment, with Volunteer guards positioned to the north of Waterford, and more on its western and eastern flanks.

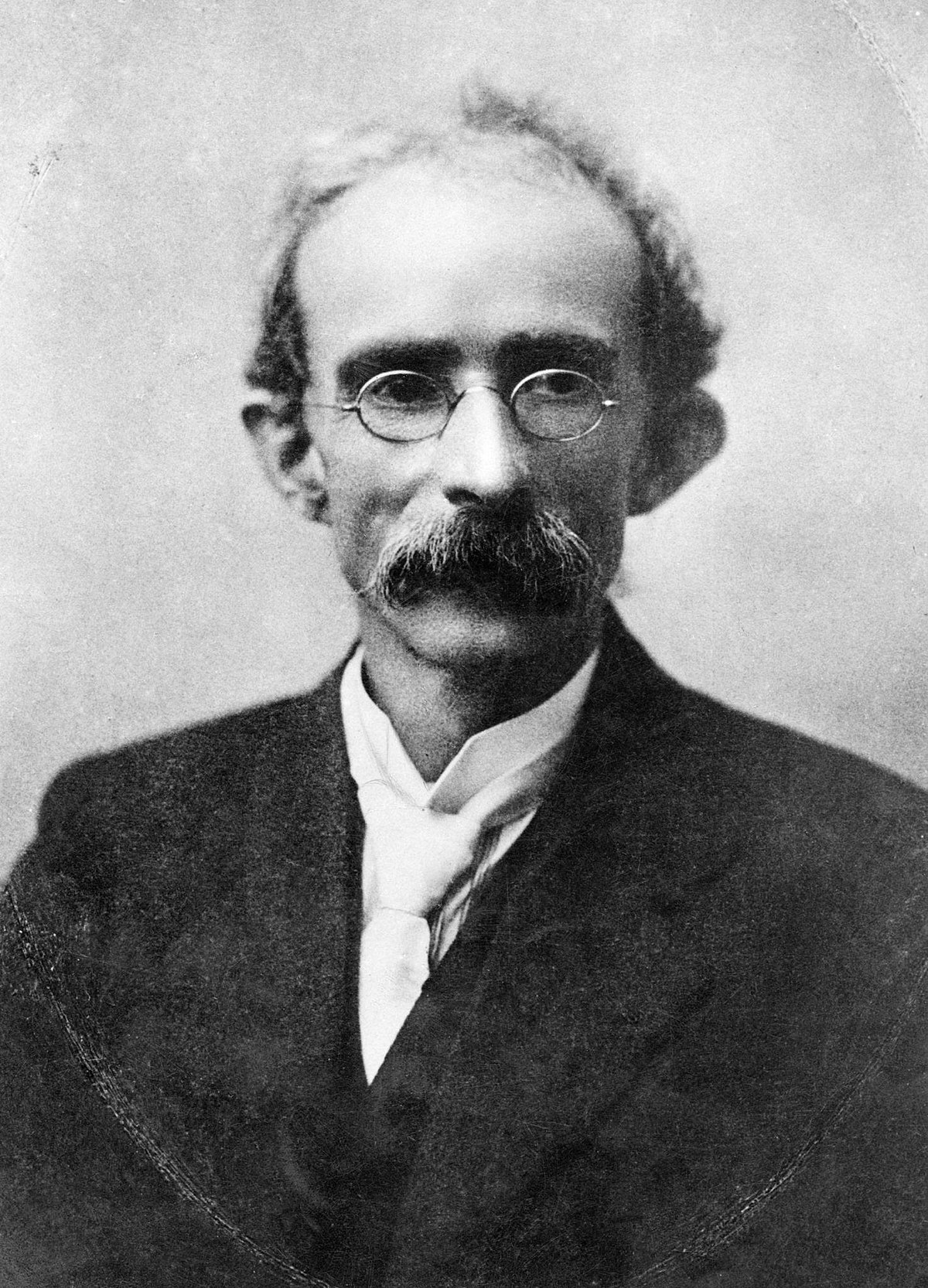

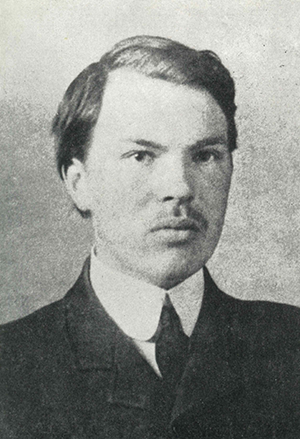

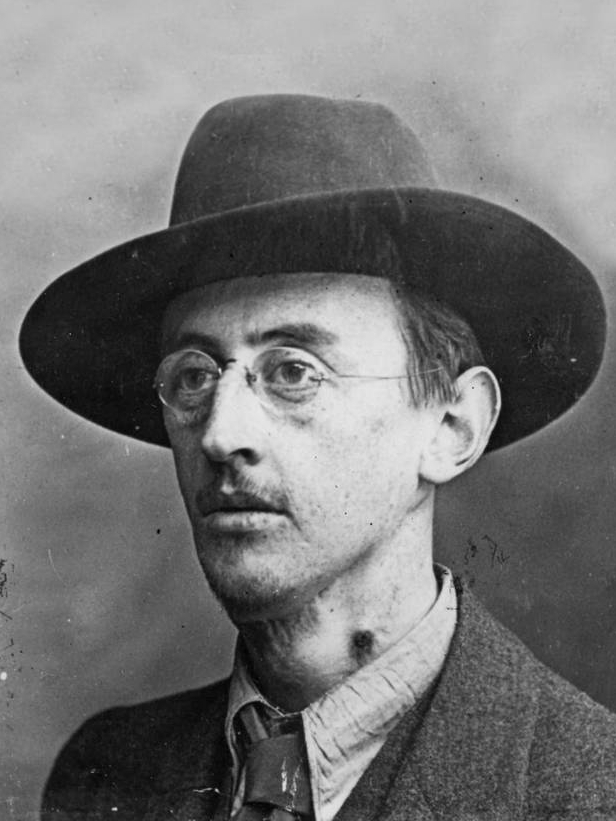

Brennan-Whitmore was one of the two GHQ operatives sent to explain to the Wexford Volunteers their part in all this. Along with Liam Mellows, he met the officers at the house of one of them in the town of Enniscorthy, sometime before Easter Week. “None of those present were told of any specific date for a rising,” Brennan-Whitmore, “but all were cautioned of the very confidential nature of the discussions; nor was anything committed to writing for obvious reasons.”

As soon as orders were received from Dublin, the Wexford men would mobilise at Enniscorthy, so chosen for its central position in the county:

Here there was to be a redistribution of arms, necessitated by the fact that while some of the corps were reasonably well armed, considering the circumstances, others were very poorly armed. A commissariat was to be set up for the provisioning of the men in the field. As soon as this task was done the local police barracks was to be invested. Every effort was to be made to achieve a quick surrender and the arms and ammunition taken at once and distributed to the corps. Meanwhile small detachments were to be sent at once to take the police barracks in outlying localities.

Once all this was done, the rebels would divide into two brigades. One was to go to Rosslare, another coastal village, in order to deny a British landing there. Since GHQ was well aware of how short of munitions the Volunteers were in general, “they were not to attempt a fight to the finish, but to retire when no longer able to maintain their positions effectively and to continue to harass the enemy in his progress inland,” as Brennan-Whitmore put it.

The second brigade was to attempt a similar role at Waterford, specifically at New Ross, north of the city, allowing them to guard against British advances via the River Barrow. Again, these men were not expected to make a last stand if things went wrong; in such an event, they would fall back to regroup at Enniscorthy and possibly try again, this time going through neighbouring Co. Wicklow and into Kildare in order to threaten the Curragh. But, whatever happened, “it was repeatedly emphasised that anything like a prolonged fight was to be avoided at all cost, and manoeuvre and harassing tactics mainly resorted to.”

It was all very ambitious and Brennan-Whitmore had his doubts as to how realistic any of it could be, considering the untrained state of the Volunteers and their paucity in weapons. As it turned out, the Wexford men never had a chance to put theory into practice, and almost lost out on having any role at all, thanks to circumstances beyond their control – the story of the Rising in a nutshell.[4]

‘An Air of Indecision’

When it finally occurred, Easter Week became less the execution of finely-honed strategies and more an exercise in improvisation.

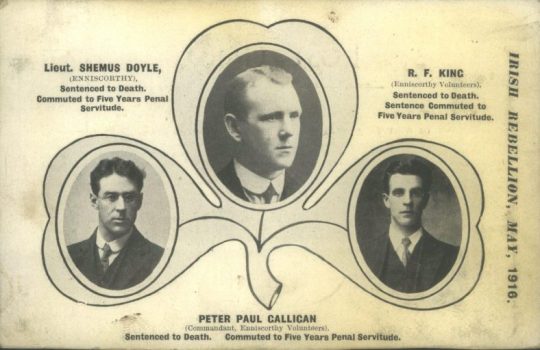

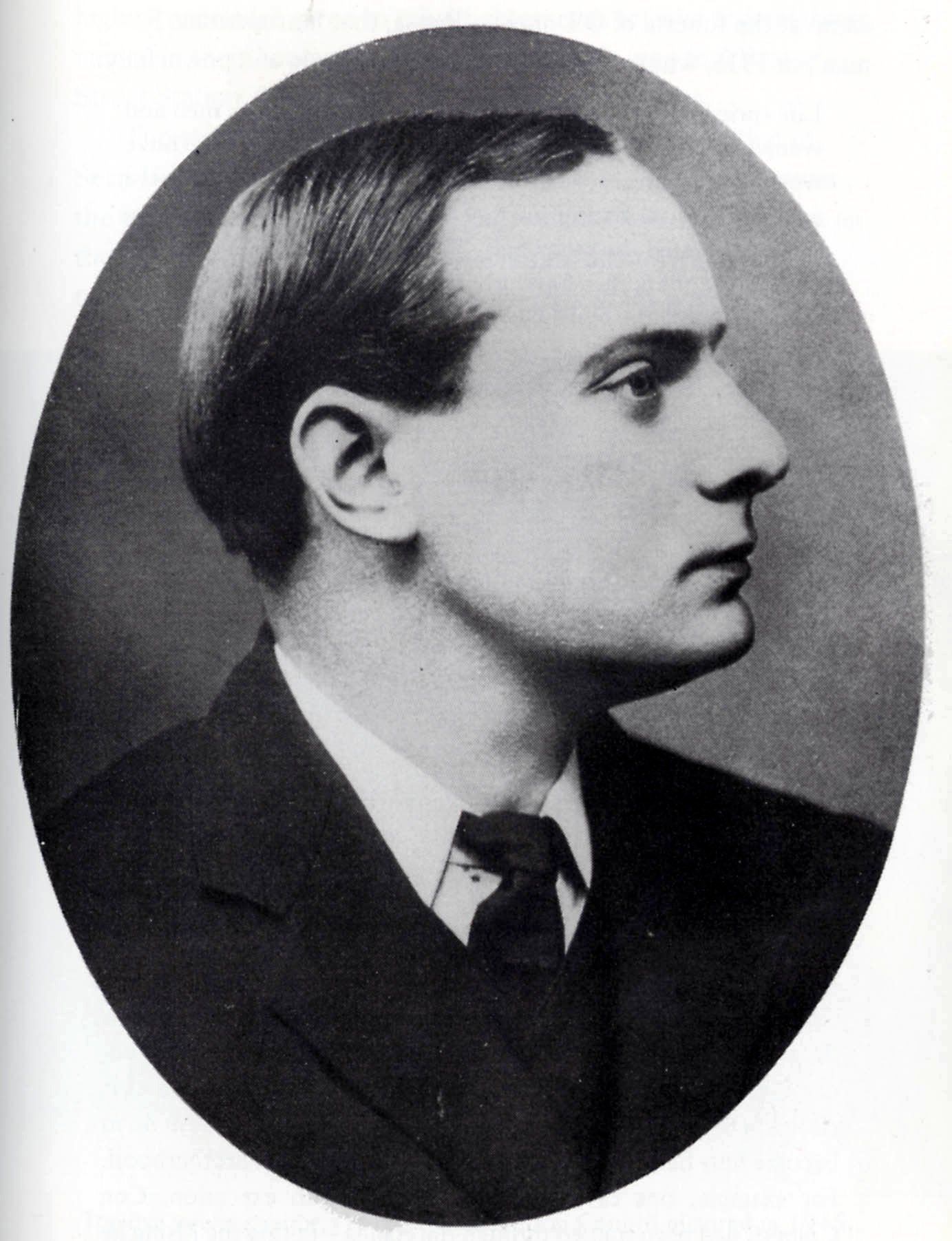

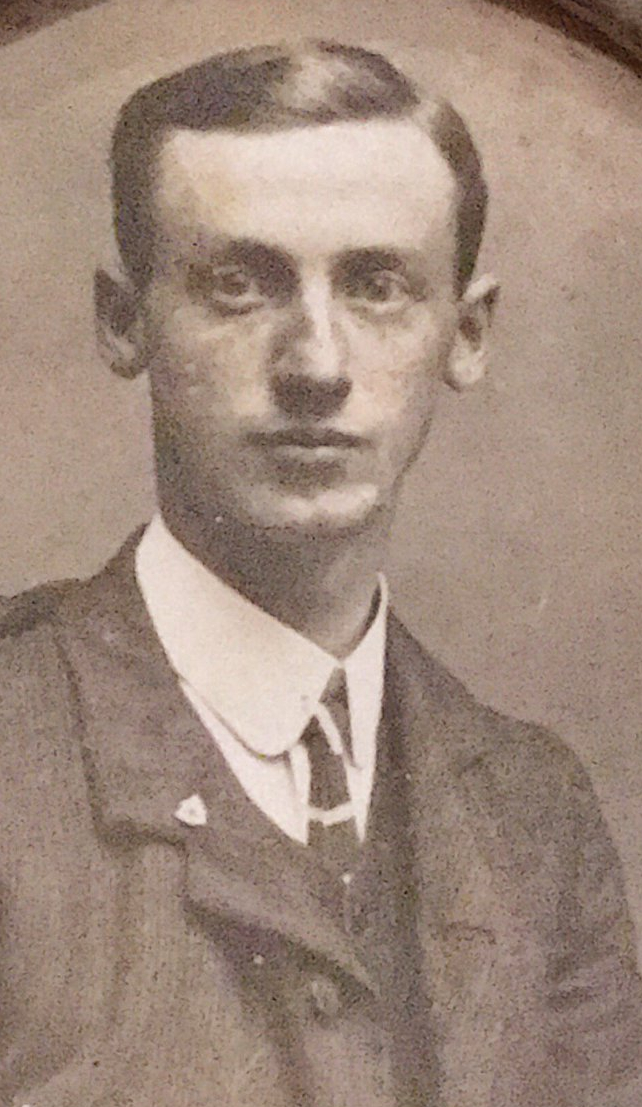

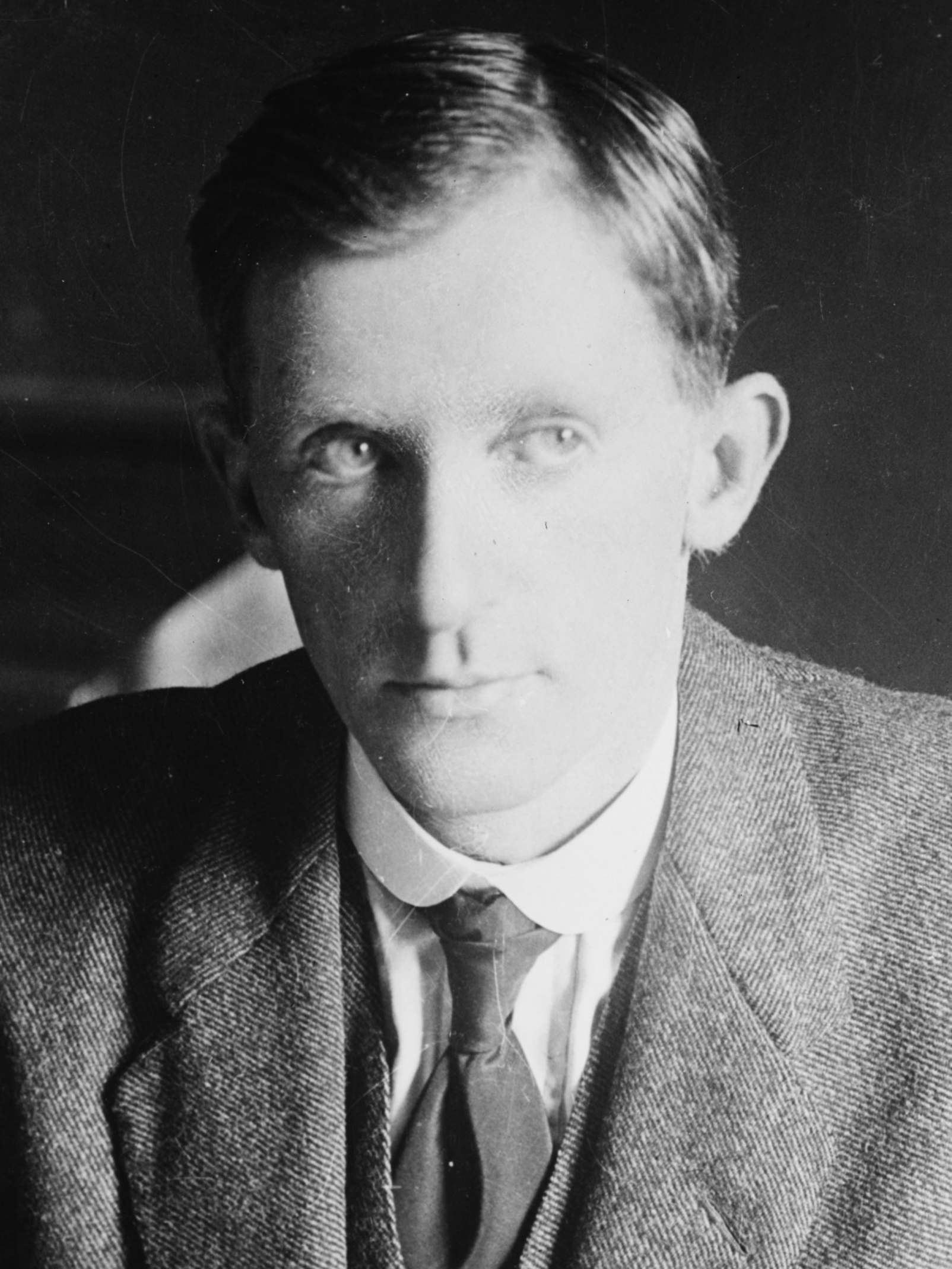

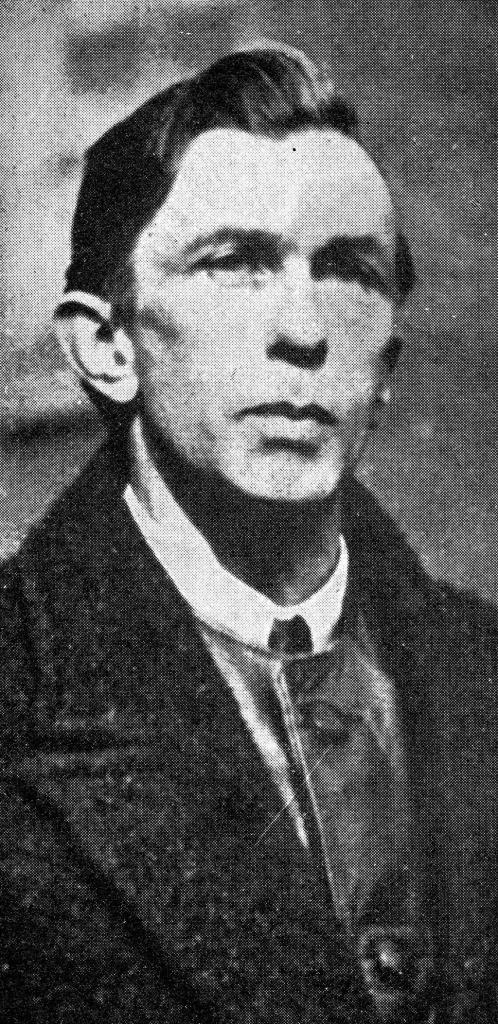

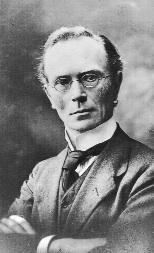

The first sign of trouble that Peter Paul Galligan saw was when Captain J.J. ‘Ginger’ O’Connell appeared in Enniscorthy on the Good Friday of Holy Week, the 21st April 1916. Galligan, as Vice-Commandant of the Enniscorthy Volunteer Battalion, was by then aware of the Rising planned in three days’ time, on Easter Sunday, a fact he had learnt from Seamus Doyle, the Battalion Adjutant. If Galligan had been surprised at this revelation, alarmed at its short notice or resentful at being informed by a colleague rather than from a superior, he gave no hint of it when it came to writing his reminiscences. A lecture the month before, in March, given by a visiting Patrick Pearse on Robert Emmet might have been a clue in itself: after all, what else was that ill-fated patriot known for besides rebellion?[5]

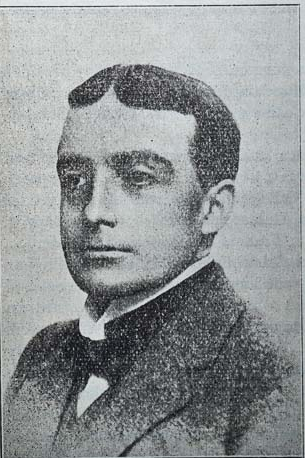

Doyle himself was aware of the incipient insurrection through his contacts in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), though he did not know the date until Pearse told him via a code he had left with him after the Robert Emmet talk. On the morning of Holy Thursday, Doyle received a message from Pearse ostensibly asking about some books available ‘on the 23rd July next. Remember 3 months earlier.’ By the dating of the 23rd July, and the ‘3 months earlier’ remark, Pearse was informing the other man that the day of action was to be the 23rd April, Easter Sunday.[6]

What was less clear was everything else. At a staff meeting attended by Galligan, Doyle and another officer, O’Connell, according to Galligan’s recollection:

…told us that he had been appointed by the Vol. Executive to take charge of Wicklow, Wexford, Carlow and Kilkenny areas, but that he refused to take over the command and would take no part in the forthcoming rising and, further, that it would be our own responsibility whatever action we took.

If O’Connell gave a reason for this startling information, Galligan did not record it. He then left Enniscorthy and that was the end of his involvement as far as the Rising was concerned. Which is perhaps just as well; all he had accomplished in his short time was disarray:

As a result of O’Connell’s action we were left without instructions and could take no further action and on Easter Sunday there was an air of indecision prevailing amongst the officers owing to this lack of instruction.[7]

Doyle was to tell the story a little differently, leaving out O’Connell for the most part, and instead it was a motorcyclist who arrived from Kilkenny “to state that as a result of the directive from GHQ that day they [the Volunteers] were not ‘rising’.” Doyle was sent by the other officers to Wexford town to discuss with their counterparts there, but “since they were also very confused about what to do,” that did not help matters.[8]

Coming to a Decision

Both Galligan and Doyle undertook journeys to Dublin to find out the facts for themselves. That they went separately and alone shows how ad hoc everything was becoming. Also indicative was that Doyle, when arriving at the Volunteer Headquarters on Dawson Street, did not bother asking Eoin MacNeill for clarification, despite the Chief of Staff being present. Instead he proceeded to the offices of the Irish Freedom newspaper in D’Olier Street to meet Seán Mac Diarmada, as one IRB initiate to another – Doyle clearly knew where the true power behind the revolution lay, or at least thought he did.

“He told me that MacNeill had consented to the Rising taking place on Easter Sunday,” in two days’ time. With this cleared up, “I travelled back to Enniscorthy that evening satisfied that everything was going well and sent this information around the other officers.”[9]

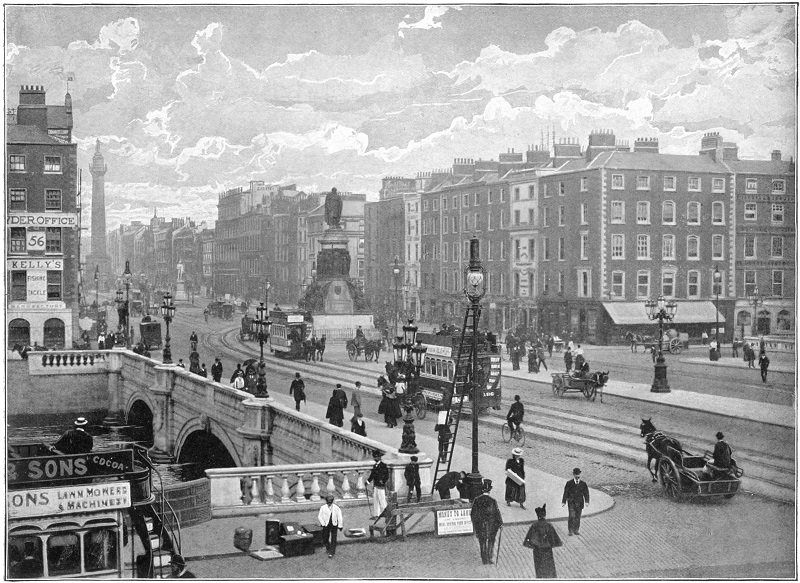

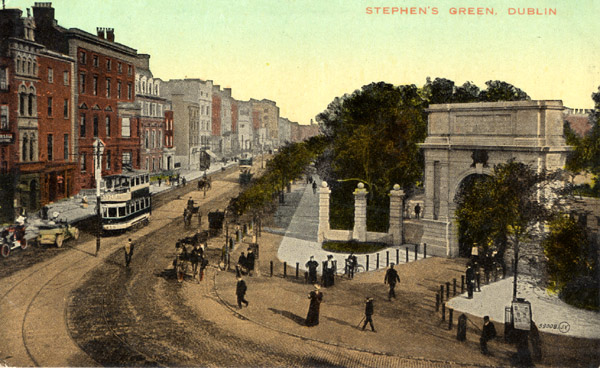

For his part, Galligan was told on the Sunday in Dublin by some acquaintances that the Rising was off for the foreseeable future. MacNeill’s countermanding order in the Irish Independent that same day confirmed it – or seemed to, as Galligan stayed in the area long enough to learn the next day that the big event was on after all.

Dublin was otherwise quiet and outwardly normal save for an overturned tramcar and a dead horse in O’Connell Street which Galligan passed on his way to the GPO. In the rebel base of operations, he reported to Pearse, along with Joe Plunkett and James Connolly. After some discussion amongst themselves, they assigned him back to his command in Enniscorthy. There, he and the rest of the Volunteers were:

…to hold the railway line to prevent [British] troops from coming through from Wexford as [Connolly] expected that they would be landed there. He said to reserve our ammunition and not to waste it on attacking barracks or such like. He instructed that I be supplied with a good bicycle.[10]

Galligan cycled home on Easter Wednesday, the 26th April, in time to give direction to an otherwise floundering battalion. The certainty of action that Doyle had brought back with him from his own trip evaporated with the publication of MacNeill’s countermanding order on the Sunday. Two contradictory messages from Pearse, the first cancelling the Rising, the next confirming it, only drove various Wexford officers to declare over the next three days their intent to do nothing. With Galligan’s return, however, came direct orders from Connolly and the rest of General Headquarters – and that finally settled the question.

“It was decided by all to start operations on Thursday morning,” Doyle recalled.[11]

Takeover

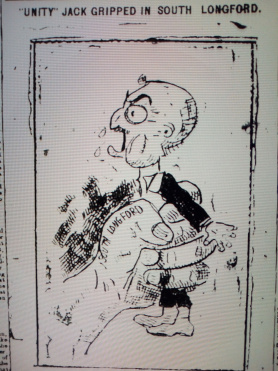

While reviewing the recent events, Mr Montague Shearman caught what looked like a discrepancy on the part of County Inspector Sharpe, one of the RIC officials testifying to the Royal Commission. The membership of the rebel movement in Wexford, Sharpe had stated, numbered at the time of the insurrection three hundred and twenty-five.

Shearman: You say there were about 325 in the county, and that 600 men turned out?

Sharpe: Yes, two hundred of them armed.

Shearman: That is about double the estimated number?

Sharpe: Oh, yes, but they terrorised the whole of the inhabitants into joining them.[12]

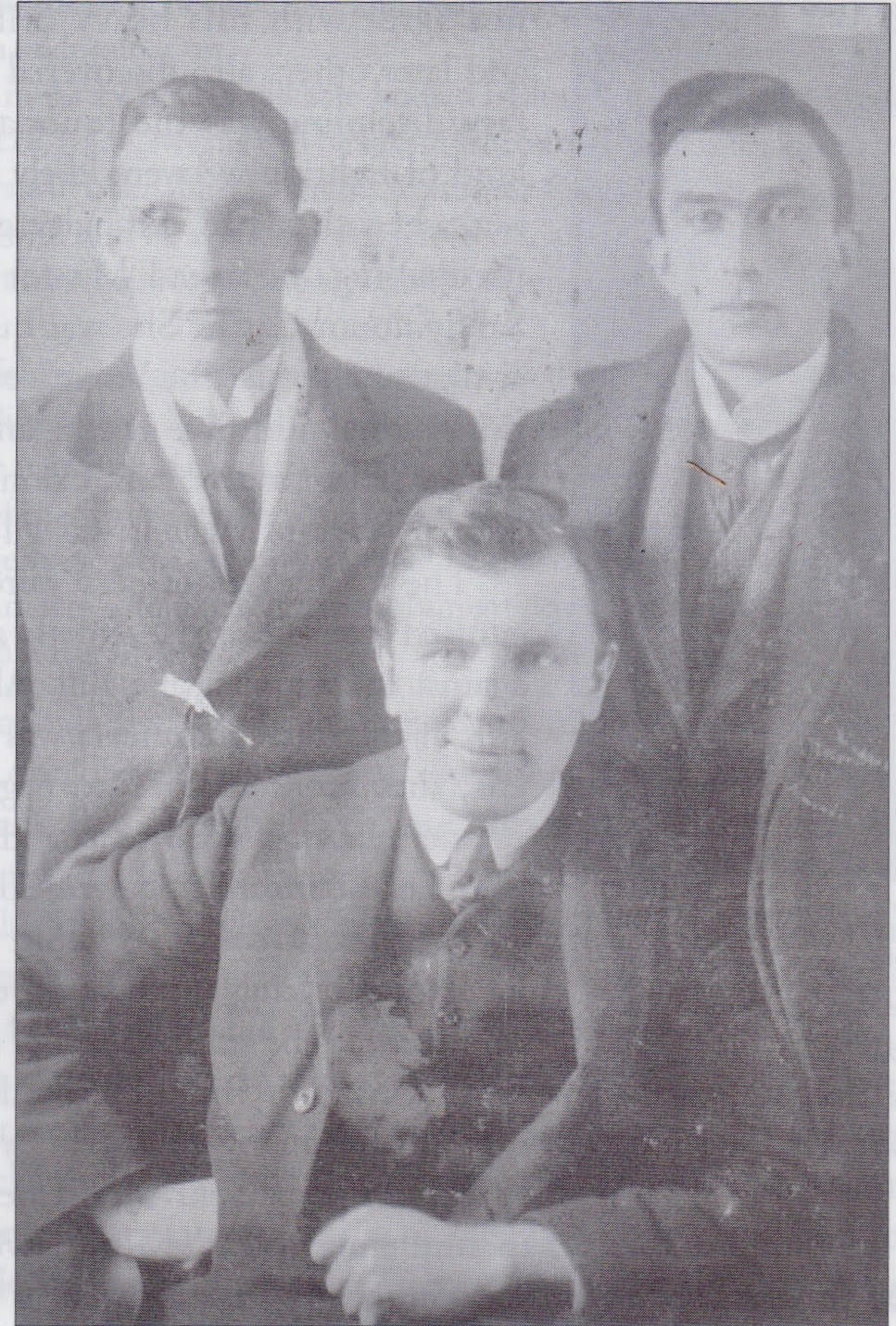

Numbers are notoriously hard for historical sources to agree upon, and personal intentions prone to contesting interpretations. Galligan put the strength of the Enniscorthy Battalion, when it was done mobilising on Thursday morning at 2 am, to about a hundred Volunteers, while Doyle had it at a hundred and fifty, at least in terms of who was armed and reliable. But both men, in their respective accounts, agreed that no one needed to be coerced; if anything, there was too much motivation and not too little.

“Large numbers were presenting themselves to join us and the feeding of these men was one of our biggest problems,” wrote Galligan, while Doyle remembered being “besieged by men wanting to join. They became a problem to feed and billet.”[13]

Another point of contention in the sources is how the Volunteers solved the aforementioned problem. County Inspector Sharpe’s report for the month of April has it that the rebels, after entering Enniscorthy, “commandeered provisions, motor cars, arms, Ammunition, etc. indiscriminately paying for nothing.” Galligan did not deny the taking of supplies from the town shops but that, as a mitigating factor:

A receipt was given in all cases for articles commandeered. It was admitted in all cases afterwards that there was no undue commandeering and no one was victimised on account of his political leaning.[14]

Another rebel officer, James Cullen, wrote in his own reminiscences of how “during the Rising the houses of nearly all the loyalists were visited by parties of Volunteers,” so the ‘no victimisation’ might not be entirely accurate. It should also be noted that Carton the blacksmith who was allegedly – according to a contemporary Irish Times report – cruelly evicted from his house near the bridge, along with his family, is not mentioned in either Volunteer or police accounts, casting the validity of that less-than-edifying episode into question.[15]

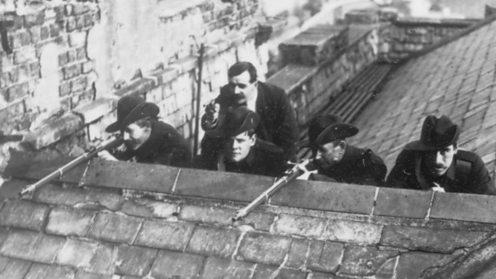

The only other ripple in the water was the small RIC force in Enniscorthy, centred in the police barracks, and consisting of six constables, a sergeant and a District Inspector. Grossly outnumbered, the policemen chose discretion as the better part of valour and withdrew to the safety of their barracks.[16]

Showing Fight

For one of them, however, the experience of Easter Thursday must have been harrowing enough, as described by a Volunteer:

At seven o’clock, Constable Grace was seen in Court St. Volunteer Mick Cahill was on duty at Mitchell’s corner, saw him crossing the road and fired at him, and only Grace took shelter in Pat Begley’s door in the corner, he would have got him. Constable Grace then made a run for the barracks…He was fired on again from the top of Castle Hill. There were a couple of Volunteers in the Convent of Msrcy [sic] field and, when he was just going into the barracks, one of them shot him in the leg. He was later brought to the hospital.[17]

A different version was provided by Father Patrick Murphy, a priest sympathetic to the uprising, in which Grace was hit and wounded while in bed, lying close to a window, rather than outside and actively participating. Another Volunteer, Thomas Sinnott, suggested that such violence was incidental rather than intentional; his commanding officer having previously told his charges “the police were not to be shot or fired at unless they themselves showed fight. He said it was against the British, we were,” and that Constable Grace had only been shot after opening fire first.

After holing up in their barracks, the remaining RIC garrison continued to be a thorn in the side of the rebels, who had to risk coming under fire when crossing the town bridge. Otherwise, the fighting in Enniscorthy was negligible, as Sinnott later explained in his interview before the Military Pensions Board:

Q: Was Thursday the only day in which there was any firing in this Period?

A: I think that would be right. There would be an occasional shot.

Q: There was no fighting or an attempt to fight?

A: No. The general opinion was, if it lasted, that the RIC would have to surrender. They were without food, tobacco, etc. – we left them the water supply though we could have cut it off.

Q: Your orders were not to attack but to defend? You were really making every effort to confine attack to the military, and regard the police as a police force, but if they attempted to use force –?

A: We would also use force.[18]

Force proved unnecessary since the RIC stayed in their stronghold until the end. No effort was made by the Volunteers to storm the building and perhaps they did not need to; for practical purposes, the Crown police force had ceased to be relevant in Enniscorthy – and, so it seemed, British governance in general.

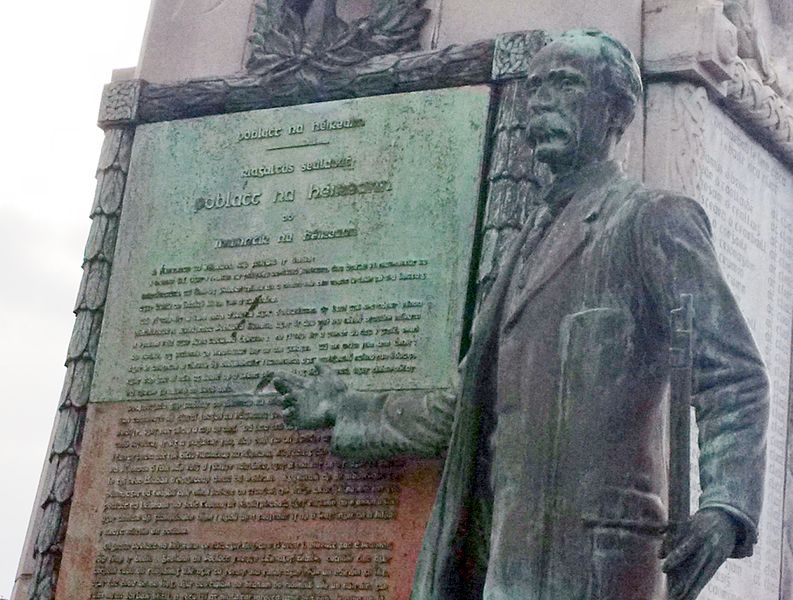

The Republic of Enniscorthy

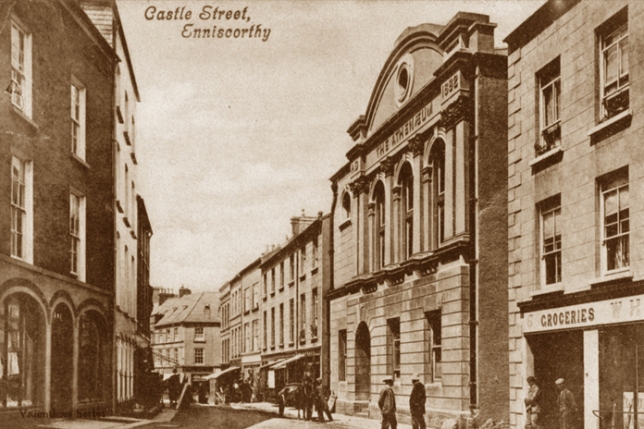

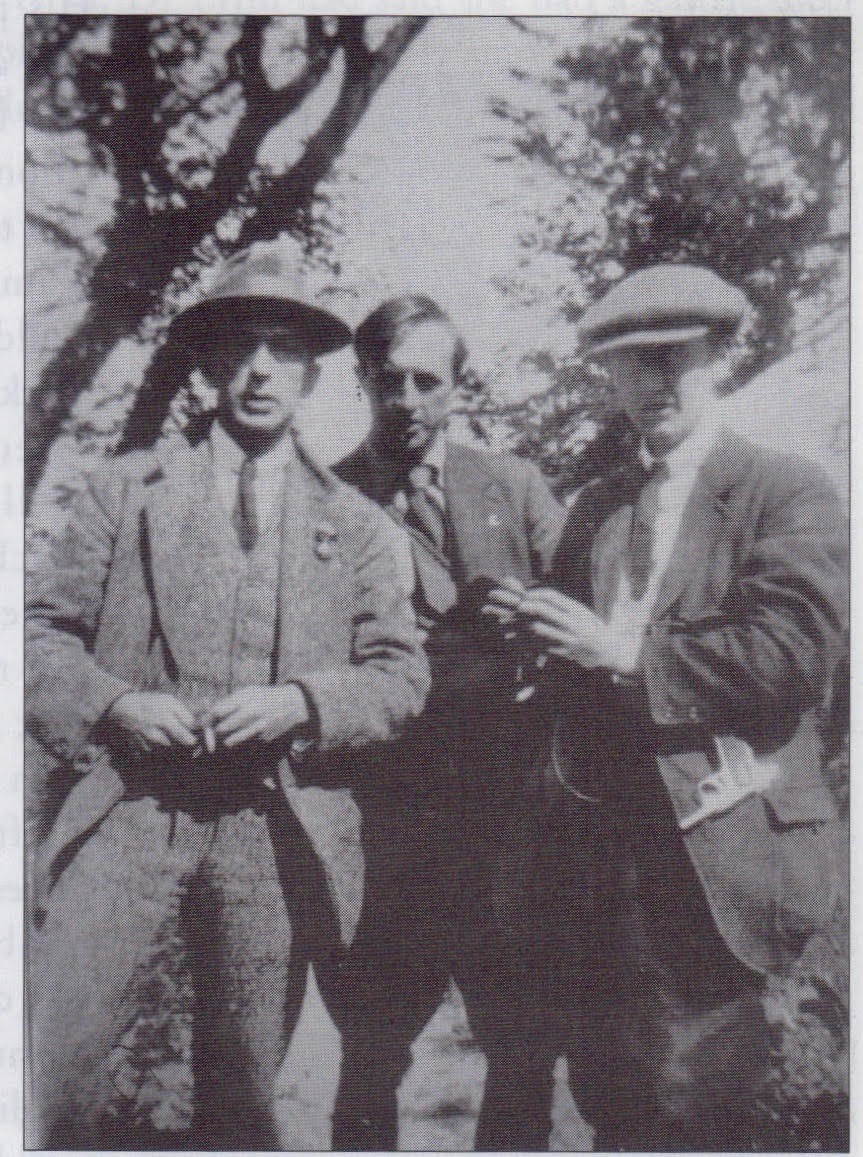

After the months of planning, almost undone by the agonising uncertainty in the eleventh hour, the takeover of Enniscorthy had proved startlingly straightforward: the Volunteers simply marched into the town and made it their own. “The Tricolour was hoisted on Headquarters with due ceremony, a Guard of Honour under Paul Galligan,” Doyle recalled. He, meanwhile, “issued a proclamation, proclaimed the Republic, and calling on the people to support it and defend” – whether he was consciously following the model set by Pearse outside the GPO on the Monday is unstated.

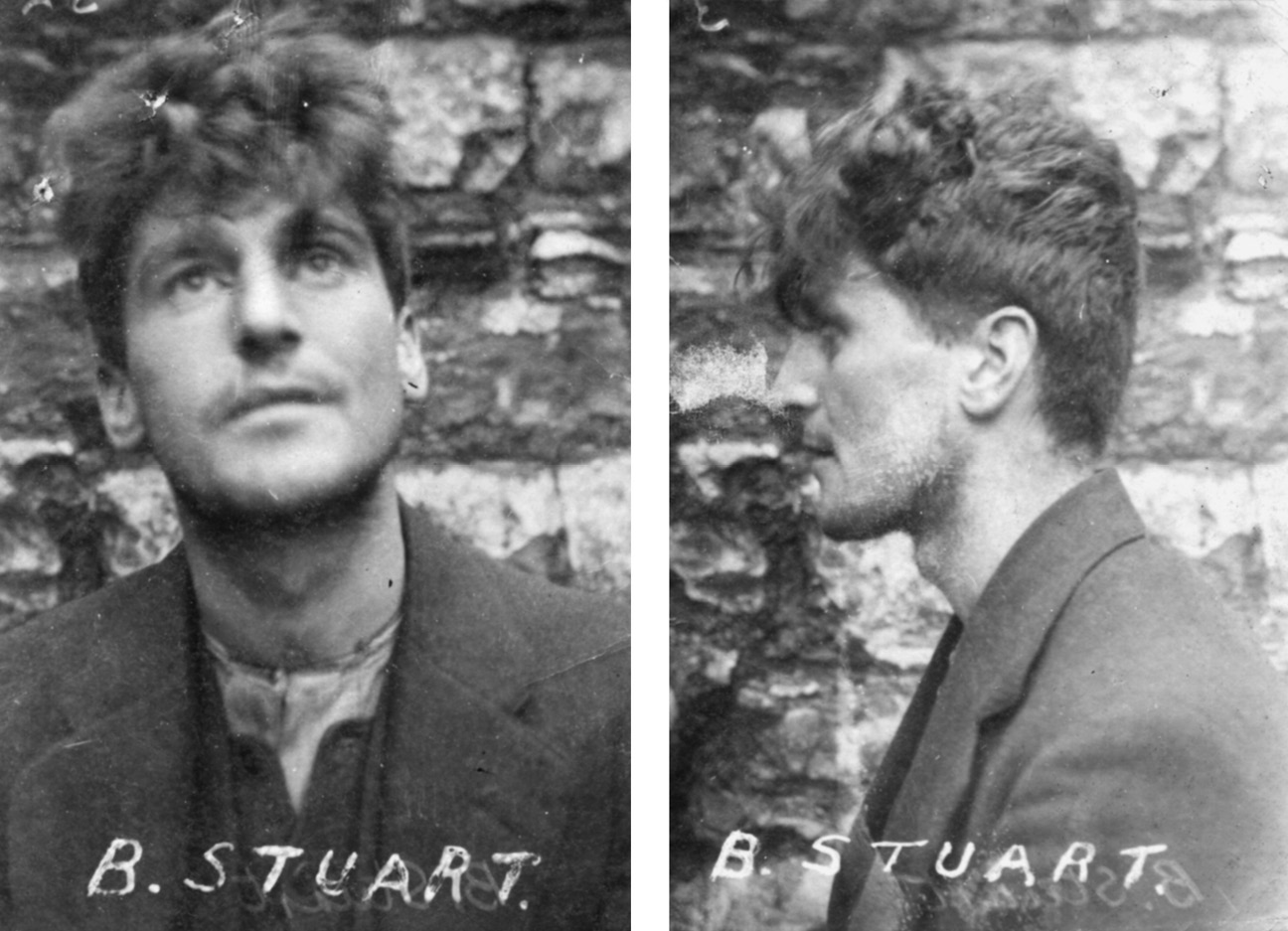

Using the Athenaeum clubhouse as their aforementioned headquarters, the officers present delegated duties, although who was doing precisely what depends on who one asks. In Doyle’s telling:

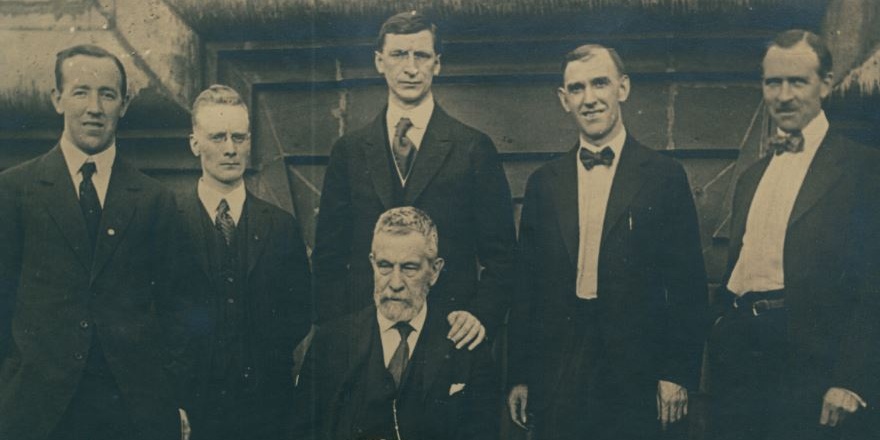

Bob Brennan took over the command. He was the senior Brigade officer. I was appointed Adjutant. Paul Galligan was appointed operations officer. Bob Brennan also acted as quartermaster. Pat Kegan looked after the armaments and Michael de Lacey looked after supplies. Phil Murphy tool charge of recruits and R.F. King was in charge of scouting operations.[19]

Galligan has Doyle as the overall O/C instead of Brennan, though he did describe the latter as “one of the driving forces during the period” [as in, the War of Independence afterwards]. Seán Etchingham was in charge of recruits, not Phil Murphy, and Michael de Lacey’s use lay in his typewriter, typing up the various orders that were to be issued. “All of our officers and most of the men were in uniform,” Galligan added. County Inspector Sharpe would later pooh-pooh the rebels as “all ne’er no wells” who had joined only having “failed in everything else” but it is clear the Enniscorthy Volunteers took their role as soldiers of the newly-found Republic very seriously; accordingly, law and order was upheld in the town by the placing of guards on the banks, along with the confiscation of keys to all pubs.[20]

“During the four days of Republican rule not a single person was under the influence of drink,” Father Murphy noted approvingly.[21]

Which was all very well, but there was still the rest of the county, and the country, to consider. Efforts were made to rouse the Volunteer units elsewhere in Co. Wexford, resulting in a mixed bag, as Galligan outlined:

A mobilisation order to mobilise his company was sent to Sean Kennedy at New Ross. He failed to do this and a second order was sent to him. Kennedy’s father met the man who carried the orders and told him that if he did not leave the town he would shoot him. New Ross never officially mobilised, but as far as I can remember a number of men reported to Enniscorthy. Ferns mobilised and sent in a full quota of men, small, of course. Wexford [town] also sent in some men.[22]

Regarding Wexford town, however, Thomas Doyle (no relation to Seamus, it seems) had nothing but scorn. Two men had been sent there on bicycles earlier in the week, on Easter Wednesday. The RIC were ready and waiting to arrest the pair as soon as they arrived. Worse almost followed. “All the loyalists turned out, which was nearly everyone in Wexford, to lynch them. Only for the police, they would have stormed the barracks,” he wrote. “We really only got one man from the Wexford Battalion. That was Wexford town for you in Easter Week!”[23]

Still, the Volunteers had enough men out in arms to attempt the primary strategy assigned to them by GHQ: the sabotage and harassment of enemy reinforcements. ‘Attempt’ proved the operative word: a mission to blow up a bridge on the railway line below Wexford town was foiled when the Volunteers so assigned were surprised by the RIC, with the loss of two taken prisoner. Another failure was the search for a trainload of ammunition from Waterford that the Volunteers heard – through friendly railway workers – was due for Arklow; despite looking through all stations between Wexford and Arklow, nothing of the sort was found. The Volunteers found smaller tasks more manageable, such as felling trees to block certain roads, and removing the railway line at various points through their control of Enniscorthy station.[24]

The Rebels of Today

The Rising was to last in Co. Wexford for four days altogether, from the belated start on Easter Thursday to its end on Monday, the 1st May 1916. A contemporary report attributed its ceasing and deceasing to a 15-pounder gun, dubbed ‘Enniscorthy Emily’, that the British military were apparently able to transport, via an armoured train, close enough to Enniscorthy to be in range of Vinegar Hill, site of the famed 1798 battle. There, the Volunteers had gathered “with the intention probably of emulating the deeds of their ancestors, but the rebels of to-day are of different stuff,” wrote the Irish Times:

A hurried council of war was held, but the deliberations were brought to an abrupt conclusion when a well planted shell which the gunner of ‘Enniscorthy Emily’ discharged at the hill. The shell, which, it is stated, was a blank one, landed plump amongst the rebels, and exploded with a prodigious and terrifying noise. When the rebels recovered somewhat from the terror-inspiring sound, they hoisted white flags all over the hill, as many as forty flags being counted, and about 200 of the ‘brave’ insurgents bolted for the hills. The others laid down their arms unconditionally, and the military have ever since been busily engaged in rounding up the stragglers.

“So began and ended the ‘war’ in the Enniscorthy district,” the newspaper concluded with a sniff and a sneer.[25]

Needless to say, at least one croppy was not going to lie down and take this. When it was time to pen his own version of events, Robert Brennan made a point of singling out “the fantastic account of this affair published at the time in the Irish Times and, later, repeated in every book I have seen on the Enniscorthy Rising,” determined as he was to set the record straight:

It is stated that the British advanced from Wexford under cover of an armoured train which had been christened “Enniscorthy Emily”, that the rebels, outfought in the town, retreated to Vinegar Hill where they finally surrendered. The fact was that the British did not enter the town until twelve hours subsequent to our decision to give up and that we never even heard of “Enniscorthy Emily”[26]

The truth was more prosaic: the Volunteers disbanded after it had been made clear to them that their insurrection was already over, without a single shot needed by either side. Peace moves had been tried before by Father McHenry, the administrator of the Enniscorthy Catholic parish – first, to the besieged policemen in their barracks on the 28th April (Day Two), and then a second try the day after, this time to Seamus Doyle. On both occasions, the would-be peacemaker failed: the RIC garrison refused Father McHenry’s call to surrender, and his argument that the rebel cause was a hopeless one “made no impression on me” as Doyle described.[27]

Well Satisfied?

What did make an impression was the news on Saturday morning of British forces moving towards them from Arklow. Galligan took personal charge of an advance guard of Volunteers posted in Ferns, the strategy being to delay the enemy there long enough for the rest to be ready in Enniscorthy. The RIC had vacated their barracks in Fens, allowing the rebels to occupy it, and to barricade the roads leading in and out of the town unmolested.[28]

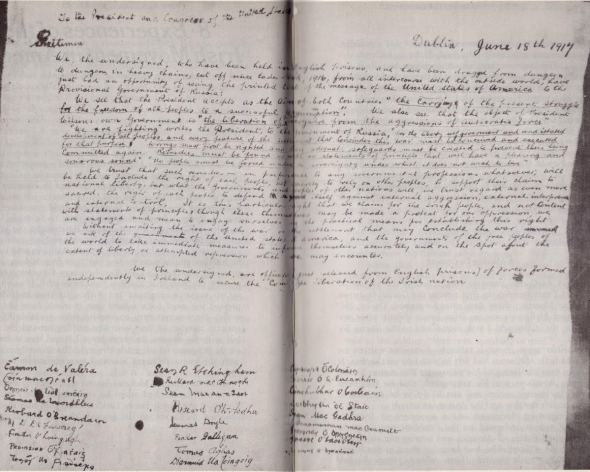

What came next was not the British attack but something quite unexpected: two RIC officials, a District Inspector and a sergeant, who had come under a flag of truce, bringing with them from Dublin a copy of Pearse’s order to surrender. Doyle had heard about this before, from a delegation of businessmen who had, like Father McHenry, been trying to broker a truce. The Enniscorthy O/C had not believed it then and did not believe it now, at least, not entirely. After consulting with the British commander in Wexford, Colonel French, it was agreed for Doyle and another officer, Seán Etchingham, to travel to Dublin under safe pass.

Once in the capital, the pair were escorted to Arbour Hill Prison, where Pearse was in his cell, lying on a mattress with his greatcoat as a blanket. “He rose quickly when the door was opened and came forward to meet us and shook hands with us,” Doyle wrote of their encounter. “He appeared to be physically exhausted but spiritually exultant.” Nonetheless, Pearse confirmed the surrender order, writing it out in a piece of paper upon Doyle’s request. He did not even know Wexford had been ‘out’, such was the speed of events and the Volunteers’ own tardiness, but he did not seem too dispirited, giving Doyle “the impression he was well satisfied with what had happened.”

The Wexford officers brought the written order back with them to Enniscorthy, allowing the rest, when called together, to see it for themselves. “The order was received with mixed opinions but finally it was decided to obey the order,” Doyle remembered. “We called in all our outposts and sentries and I read the order to the garrison. This was about midnight [on Sunday].” By 4 pm on Monday, the 1st May, Colonel French entered Enniscorthy with his soldiers and accepted the surrender. If Wexford had entered the Rising late, it at least could claim the distinction of being the last to leave.[29]

A month later, County Inspector Sharpe was pleased to report to his superiors that “the County is at present peaceable except Enn. [Enniscorthy] District and a small portion of the Gorey District which adjoins Enn.” Seditious sentiments seemed limited to “the relatives and associates of the rebels”; in the other areas, Sharpe estimated that three-quarters of the people were hostile to the recent upheaval. “There are rumours of another rising at Whitsuntide but there is no indications [sic] in the County that it will take place.”[30]

Even those committed to carrying on the struggle against British rule could not have disagreed with this self-confident appraisal. When Máire Comerford tried rousing a crowd in Main Street, Gorey, with what she had heard about North King Street in Dublin (where fifteen men had been shot or bayoneted to death by Crown forces) at least one listener was outraged – at Comerford for criticising British troops rather than at the massacre. The rest of her audience rapidly dispersed, the shock of such disloyal talk evidently too much for them. Come the same time the following year, in 1917, and Wexford did not even bother with a commemoration for the Rising. Comerford only learnt about the one in Dublin from reading about it in the newspapers – when the ceremony was already over.[31]

Still, it was too soon for the British state to be relaxing its guard quite yet. “Hide the arms,” Pearse had whispered to Doyle and Etchingham in his prison cell when the wardens were out of earshot. “They will be wanted later.” Some Wexford Volunteers chose to do just that, like Thomas Sinnott and the two rifles he buried before his arrest for his part in the Rising. “They were afterwards resurrected,” as he put it.[32]

See also:

Dysfunction Junction: The Rising That Wasn’t in Co. Kerry, April 1916

Still Waters Running Deep: The Tragedy at Ballykissane Pier, April 1916

Defeat From The Jaws of Victory: The Easter Rising in Co. Louth, 1916 (Part I)

Victory From The Jaws of Defeat: The Easter Rising in Co. Louth, 1916 (Part II)

References

[1] Gannon, Darragh. Proclaiming a Republic: Ireland, 1916 and the National Collection (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, 2016), p. 265 ; Doyle, Eamon, ‘Wexford 1916’, History Ireland, published in Issue 6 (November/December 2015) Letters, Volume 23

[2] Irish Times, 29/04/1916

[3] Ibid, 29/05/1916

[4] Brennan-Whitmore, W.J. Dublin Burning: The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2013), pp. 22-4

[5] Galligan, Peter Paul (BMH / WS 170), pp. 7-8

[6] Doyle, Seamus (BMH / WS 315), pp. 7-8

[7] Galligan, pp. 7-8

[8] Doyle, Seamus, pp. 8-9

[9] Ibid, pp. 9-10

[10] Galligan, p. 8

[11] Doyle, Seamus, pp. 10-2

[12] Irish Times, 29/05/1916

[13] Galligan, pp., 9-10 ; Doyle, Seamus, p. 12

[14] Police reports from Dublin Castle records (National Library of Ireland – NLI), POS 8540 ; Galligan, p. 10

[15] Cullen, James (BMH / WS 1343), p. 6 ; Irish Times, 29/04/1916 (Carton’s eviction)

[16] Irish Times, 29/05/1916 (makeup of police force)

[17] Doyle, Thomas (BMH / WS 1041), p. 22

[18] Murphy, Patrick (BMH / WS 1216), p. 4 ; Military Service Pensions Collection, ‘Sinnott, Thomas D.’ (WMSP34REF24701), pp. 24-5

[19] Doyle, Seamus, pp. 12-13

[20] Galligan, pp. 10, 12 ; Irish Times, 29/05/1916

[21] Murphy, p. 4

[22] Galligan, p. 11

[23] Doyle, Thomas, p. 20

[24] Galligan, pp. 10-1

[25] Irish Times, 29/04/1916

[26] Brennan, Robert (BMH / WS 779 – Part I), p. 147

[27] Irish Times, 29/05/1916 ; Doyle, Seamus, p. 13

[28] Galligan, p. 12

[29] Doyle, pp. 14-6

[30] NLI, POS 8541

[31] Comerford, Máire (ed. by Dully, Hilary) On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2021), pp. 60, 64-5

[32] Doyle, p. 15 ; Sinnott, p. 26

Bibliography

Newspaper

Irish Times

Books

Brennan-Whitmore, W.J. Dublin Burning: The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2013)

Comerford, Máire (ed. by Dully, Hilary) On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2021)

Gannon, Darragh. Proclaiming a Republic: Ireland, 1916 and the National Collection (Newbridge, Co. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, 2016)

Bureau of Military History Statements

Brennan, Robert, WS 779

Cullen, James, WS 1343

Doyle, Seamus, WS 315

Doyle, Thomas, WS 1041

Galligan, Peter Paul, WS 170

Murphy, Patrick, WS 1216

Military Service Pensions Collection

Sinnott, Thomas D., WMSP34REF24701

Magazine

Doyle, Eamon, ‘Wexford 1916’, History Ireland, published in Issue 6 (November/December 2015) Letters, Volume 23

National Library of Ireland Collection

Police Report from Dublin Castle Records

Three days later, on the 11th March, he believed he had his answer:

Three days later, on the 11th March, he believed he had his answer:

But that had been then, and this was now, and the sundering they hoped to avoid had come after all. Which should not be Labour’s concern, said O’Shannon, as he urged his audience:

But that had been then, and this was now, and the sundering they hoped to avoid had come after all. Which should not be Labour’s concern, said O’Shannon, as he urged his audience:

“When the present issue was decided between Free Staters versus Republicans, then the time would come to launch their policy,” but, until then, Keyes:

“When the present issue was decided between Free Staters versus Republicans, then the time would come to launch their policy,” but, until then, Keyes:

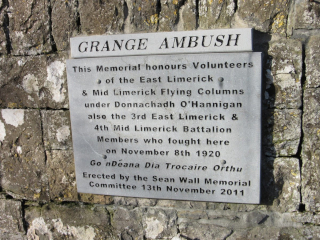

If this was mainstream opinion, then resisting this consensus were men like Thomas Hearty, a former Fenian, who McGuill saw on Easter Thursday, returning to Dundalk from Dunboyne, Co. Meath. The Louth Volunteers had reached it, though Commandant O’Hannigan ordered Hearty back on account of his advanced age and the poor state of the horse pulling his hackney carriage. Though denied his chance at glory with the rest of the Louth contingent and their Meath comrades, the two groups having joined up as planned, Hearty had at least witnessed a tricolour fluttering over the marching ranks.

If this was mainstream opinion, then resisting this consensus were men like Thomas Hearty, a former Fenian, who McGuill saw on Easter Thursday, returning to Dundalk from Dunboyne, Co. Meath. The Louth Volunteers had reached it, though Commandant O’Hannigan ordered Hearty back on account of his advanced age and the poor state of the horse pulling his hackney carriage. Though denied his chance at glory with the rest of the Louth contingent and their Meath comrades, the two groups having joined up as planned, Hearty had at least witnessed a tricolour fluttering over the marching ranks.

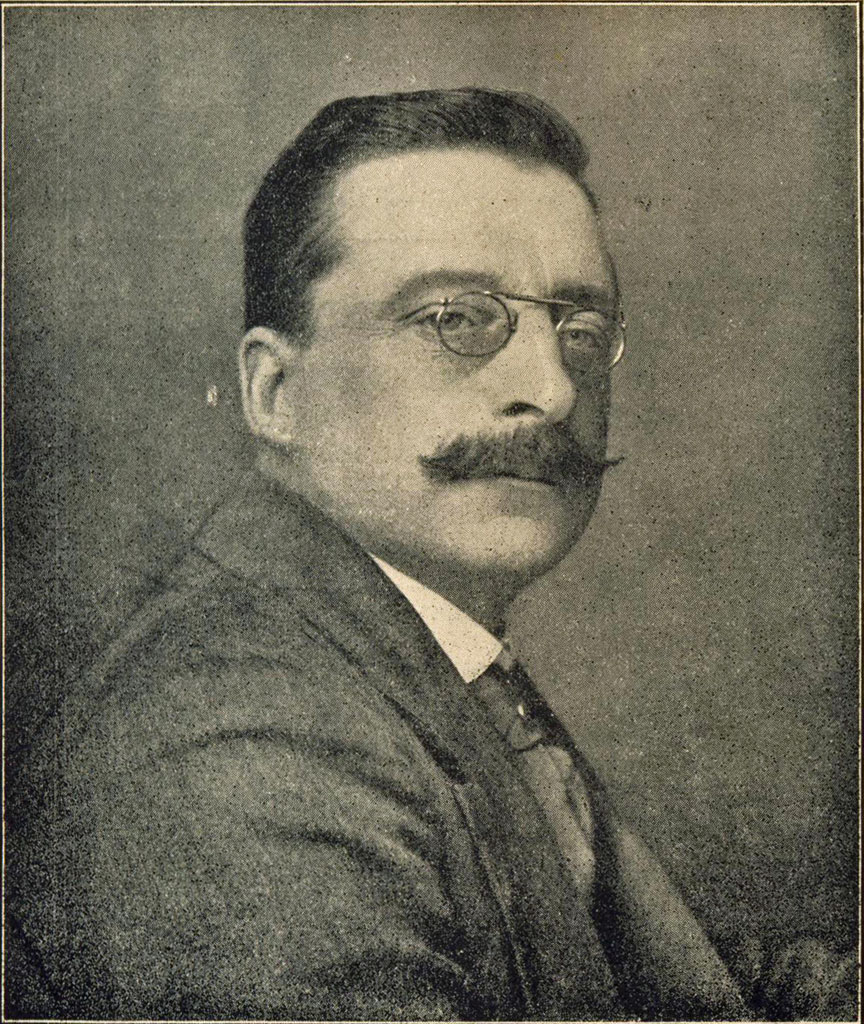

It was not the first step in what was to be a long and distinguished career for MacEntee – Easter Week could claim to be that start, for without the Rising, there would have been nothing and almost certainly a very different future for Ireland. But not everyone would have a future, a fact MacEntee was evidently aware of, for he took time out of his busy electioneering tour to visit Inishbofin and pay his condolences to the family of Constable McGee.

It was not the first step in what was to be a long and distinguished career for MacEntee – Easter Week could claim to be that start, for without the Rising, there would have been nothing and almost certainly a very different future for Ireland. But not everyone would have a future, a fact MacEntee was evidently aware of, for he took time out of his busy electioneering tour to visit Inishbofin and pay his condolences to the family of Constable McGee.

Which is a matter of opinion, perhaps, but keeping one hand ignorant of the other’s doings – the strategy the Easter Rising was built on – would certainly prove to have repercussions no less unfortunate.

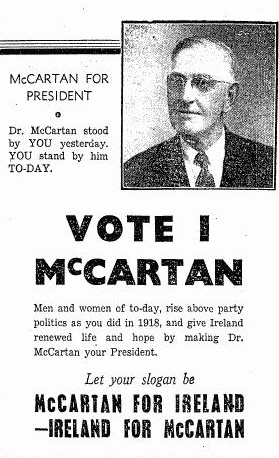

Which is a matter of opinion, perhaps, but keeping one hand ignorant of the other’s doings – the strategy the Easter Rising was built on – would certainly prove to have repercussions no less unfortunate. That McCartan was running at all was a surprise, considering he had only just about secured the minimal number of signatures on his nomination papers, these being from TDs and senators in the Farmers Party. This was despite McCartan not standing on their platform, or for any faction for that matter, as opposed to the blocs – and powerful ones at that – behind the other two contenders: Fianna Fáil for O’Kelly and Fine Gael for Mac Eoin.

That McCartan was running at all was a surprise, considering he had only just about secured the minimal number of signatures on his nomination papers, these being from TDs and senators in the Farmers Party. This was despite McCartan not standing on their platform, or for any faction for that matter, as opposed to the blocs – and powerful ones at that – behind the other two contenders: Fianna Fáil for O’Kelly and Fine Gael for Mac Eoin.

Making Sense of Things

Making Sense of Things

Contradictory Conflictions

Contradictory Conflictions

But patriotic productions were only part of the agenda for McCartan and his stateside peers. Whatever its faults as a military operation, the 1916 Rising had at least set the Irish revolution in motion, and McCartan, whatever his private views about the Easter Week of the year before, was eager to play his part. When Czira told him that a German friend of hers, Lucie Haslau, had bade farewell to some of her compatriots from the German Embassy who were homebound, given the state of war that now existed between their country and America, McCartan was surprised – and intrigued.

But patriotic productions were only part of the agenda for McCartan and his stateside peers. Whatever its faults as a military operation, the 1916 Rising had at least set the Irish revolution in motion, and McCartan, whatever his private views about the Easter Week of the year before, was eager to play his part. When Czira told him that a German friend of hers, Lucie Haslau, had bade farewell to some of her compatriots from the German Embassy who were homebound, given the state of war that now existed between their country and America, McCartan was surprised – and intrigued.

The subsequent meeting was at least well attended, with the entire Brigade and battalion staff present, as was the Divisional O/C. Despite the floundering of his own efforts, O’Malley was a particularly useful addition, having spent time in Limerick as an IRA operative, and was able to fill O’Duffy in on some of the local context:

The subsequent meeting was at least well attended, with the entire Brigade and battalion staff present, as was the Divisional O/C. Despite the floundering of his own efforts, O’Malley was a particularly useful addition, having spent time in Limerick as an IRA operative, and was able to fill O’Duffy in on some of the local context:

To his shock, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) dominated the streets in a way it had ceased to do elsewhere in Ireland, its blue-uniformed sergeants and constables swaggering about “with impunity, largely because of almost complete inactivity on the part of the Volunteers in Limerick City. Apart from two or three incidents of no great magnitude, this situation persisted up to the Truce.”

To his shock, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) dominated the streets in a way it had ceased to do elsewhere in Ireland, its blue-uniformed sergeants and constables swaggering about “with impunity, largely because of almost complete inactivity on the part of the Volunteers in Limerick City. Apart from two or three incidents of no great magnitude, this situation persisted up to the Truce.”

Stepping Up

Stepping Up

Nugent seems to have been equally blasé in his own way, for he continued on to his shop at 9 Lower Baggot Street. When Captain Cullen came in with another man who was – incongruously enough – carrying half a ham and some mutton, Nugent sent them upstairs, out of sight from his customers, for he recognised Cullen’s companion as Rory O’Connor, a leading figure in the Irish Volunteers.

Nugent seems to have been equally blasé in his own way, for he continued on to his shop at 9 Lower Baggot Street. When Captain Cullen came in with another man who was – incongruously enough – carrying half a ham and some mutton, Nugent sent them upstairs, out of sight from his customers, for he recognised Cullen’s companion as Rory O’Connor, a leading figure in the Irish Volunteers.

Patrick Little was one of his allies in this venture. If before Little had been dipping his toe in radical politics, now he threw himself in wholeheartedly, having had his offices in Eustace Street, where he did his work as a solicitor, trashed by British soldiers during Easter Week. When a rifle was found on the premises, the soldiers dragged out the son of the caretaker into the narrow lane at the back of the building, where they shot him.

Patrick Little was one of his allies in this venture. If before Little had been dipping his toe in radical politics, now he threw himself in wholeheartedly, having had his offices in Eustace Street, where he did his work as a solicitor, trashed by British soldiers during Easter Week. When a rifle was found on the premises, the soldiers dragged out the son of the caretaker into the narrow lane at the back of the building, where they shot him.

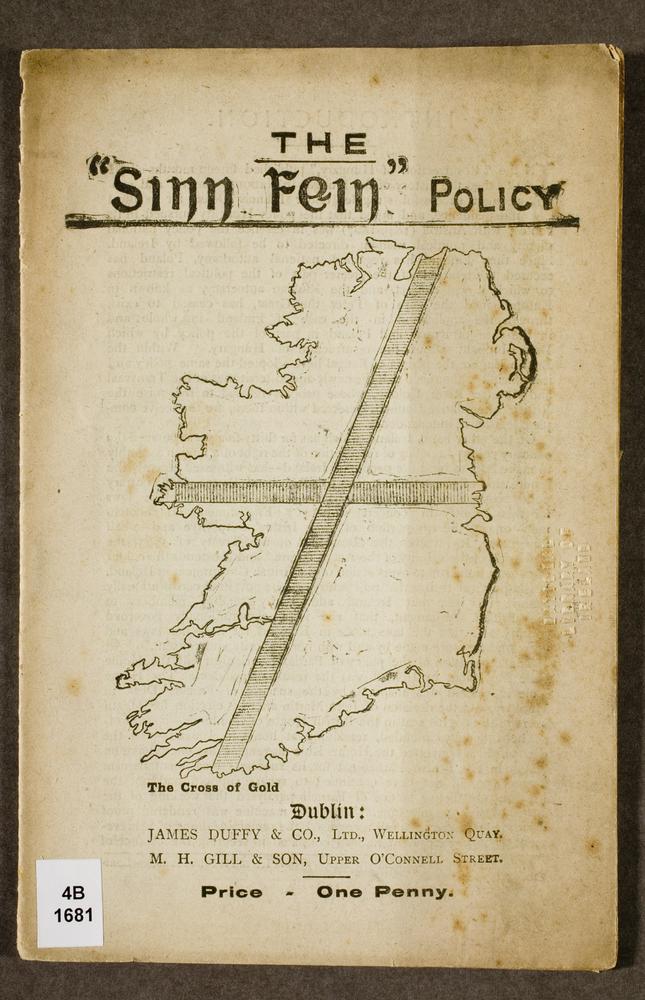

“As Ireland became pro-insurrection she became Sinn Féin, without knowing what Sinn Féin was,” was how one contemporary described the phenomenon, “except that it stood generally for Irish independence in the old complete way, the way in which the Irish Party had not stood for it.”

“As Ireland became pro-insurrection she became Sinn Féin, without knowing what Sinn Féin was,” was how one contemporary described the phenomenon, “except that it stood generally for Irish independence in the old complete way, the way in which the Irish Party had not stood for it.” Things went even worse for Smyth later that day. He was so angry that he refused to let Nugent come with him and Father Lavan in the car to Slatta Chapel, where the two representatives were due to appear next.

Things went even worse for Smyth later that day. He was so angry that he refused to let Nugent come with him and Father Lavan in the car to Slatta Chapel, where the two representatives were due to appear next.

To each of these dissenters, O’Connor would dispatch a letter, saying:

To each of these dissenters, O’Connor would dispatch a letter, saying:

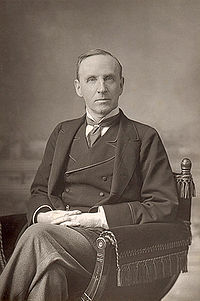

John Morley was a worried man despite his recent elevation. He had just been appointed as Irish Chief Secretary, a role he was regarding with considerable dubiety. This he sought to assuage by a talk, on the 17th October 1892, with a man who had his ear to the ground of that troubled – and, from the point of view of many in the British Government, troublesome – quarter of the United Kingdom.

John Morley was a worried man despite his recent elevation. He had just been appointed as Irish Chief Secretary, a role he was regarding with considerable dubiety. This he sought to assuage by a talk, on the 17th October 1892, with a man who had his ear to the ground of that troubled – and, from the point of view of many in the British Government, troublesome – quarter of the United Kingdom.