“It is a true fact that the greatest swordsman in Italy would not fear the second greatest but would fear the worst, for that one would be unpredictable” – The Masque of Red Death (1964)

A Simple Soul

Towards noon on Easter Monday 1916, Monsignor Michael J. Curran received word that Count George Plunkett was waiting outside his office. Guessing that this would be about some new development in the unfolding, but so far still uncertain, situation in Dublin, Monsignor Curran agreed to see him.

Five minutes later, Curran was sitting with the Count, grey-haired and bearded. His caller asked to see the Archbishop of Dublin, Dr William Walsh, to whom Curran was secretary. Curran replied that His Grace was ill in bed and not to receive anyone except his doctor.

Which was not entirely true but the Monsignor’s duties included acting as gatekeeper to his master. Things were tense enough as it was, what with the news of Roger Casement’s arrest in Kerry, the planned mobilisation of the Irish Volunteers and the abrupt countermanding orders by their Chief of Staff, Eoin MacNeill.

“Well,” said the Count, according to Curran’s recollections, “it is not necessary that I see him personally but, if you would tell him, it would be alright.”

Plunkett proceeded to inform Curran that there was going to be an uprising in Ireland and that he had already visited Pope Benedict XV in Rome to inform him of such. His Holiness had been asked not to be shocked or alarmed as the rebellion was to be purely in pursuit of the same independence that every country was entitled to. The Count had then asked for the Pontiff’s blessing for the endeavour.

Monsignor Curran was still listening to the story when the telephone rang in his office. Curran answered it to learn that the General Post Office (GPO) had just been seized and occupied by the Irish Volunteers. He returned to inform his visitor that the uprising the latter had warned about was already underway. Curran would later consider it noteworthy that Plunkett had come to him on the day the rebellion began and not before, presumably to leave no window of opportunity for the Archbishop to change anyone’s mind.

Once his visitor had left, Curran hurried to relay what had occurred to his superior. Even after being told the Count’s message, Walsh was more concerned about what MacNeill, rather than Plunkett, might do, looking upon the Count as less of a leader and more “as a simple soul and [he] could not conceive a man like him being at the head of a revolution.”[1]

A Conservative Catholic Gentleman

The Archbishop’s scepticism was understandable, considering how the Count had never shown a radical bone in his body. As far as many were concerned, he was simply:

…a conservative Catholic gentleman with harmless literary and cultural tastes which his job as Director of the National Gallery (bestowed on him by the Liberal Government) gave him ample time and opportunity to indulge in.[2]

This, at least, was the view of the political activist Kevin O’Shiel. It was not an altogether wrong one, though O’Shiel was incorrect about the Gallery. According to Geraldine Plunkett, her father had been offered its directorship by Dublin Castle in the spring of 1916 on the condition that his family stay out of politics but he defiantly turned it down (being already the director of the National Museum, which was probably what O’Shiel meant).[3]

Similar sentiments were expressed by William O’Brien, a trade unionist who had been closely involved in the planning of the Rising. O’Brien knew very little about Plunkett by the time the latter grew in prominence in early 1917, only that he had previously only seen his name “in connection with various projects supported by people of the Unionist type.” Whatever else about the Count, O’Brien certainly did not think of him as much of a Nationalist.[4]

In fact, the Count had had a reasonably active time in politics as a Nationalist, and an honourable one at that. This tended to be overlooked, much like how Walsh, O’Shiel and O’Brien were content to discount the man in general. And yet, for a while, it looked as if the post-Rising upheaval would be regarded as the Plunkett Revolution.

Early Years

Born in 1851 as a privileged scion of an illustrious name (the 17th century St. Oliver Plunkett was an ancestor), George Noble Plunkett was sent abroad to a Jesuit school in Nice at the age of six. The reason for this was to protect his health and, as he was the only one of his three siblings to survive to adulthood, this may have been a wise precaution.

Recently ceded to France by Italy, Nice was at a cultural crossroads, and there young George grew up fluent in French, Italian and Niçoise. George, according to a flattering write-up in the Catholic Bulletin, was sufficiently immersed in such a cosmopolitan environment to temporarily forget English but he remained, nonetheless, “in feeling intensely Irish.”[5]

This may be a slight exaggeration as he was not to return to Ireland until 1862, aged eleven. Afterwards, though, he would have ample opportunity to show the intensity of these Irish feelings of his.

Even at an early age, his passion for art, literature and other forms of high culture was evident. He became a regular visitor to various art galleries in Europe, and collected a string of presidencies or vice-presidencies at societies such as the Academy of Christian Science, the Royal Irish Academy and the Society of Catholic Poetry.[6]

George soon developed a system on how best to explore a gallery: (1) a visit should never last more than two hours, for past that and mental fatigue sets in, (2) always focus on the best pieces even to the exclusion of the rest (advice he was happy to pass on to anyone interested).[7]

George made his mark on the literary scene when he published a collection of his poetry, God’s Chosen Festival (A Christmas Song) and Other Poems in 1877. Many of the poem titles – such as ‘Ave Maria’, ‘The Sleep of the Infant Jesus’ and ‘An Orphan’s Prayer to the Blessed Virgin’ – display a distinctly Catholic sensibility, with the occasional foray into Irish nationalism, such as in ‘To Ireland’, where he laments the subject’s history:

Woe! Woe! That we cannot blot

The records of countless crimes!

For the blood and tears you shed

Leave their strains to the latest times.

But worst of the heartless foes

That his hand hath deep imbed

In the warm hearts-blood of our Nationhood,

Is that monster, Ingratitude.[8]

Another, ‘Erinn’, both celebrates his homeland while hinting at the poet’s status as a world traveller:

Fair is God’s world!

I have wondered it tho’:

Fancy’s unfurled

His best scenes to my view;

When seems the fairest,

Of all the bright earth –

The dearest, the rarest?

The land of my birth!

Golden expanse

Poetized by the Rhine,

Gay land of France,

Repose of wit and of wine,

But one can claim –

Though it hath not the smile

Of Italy – the name

Of the Emerald Isle![9]

Upon reviewing some later poems of Plunkett’s in 1921, the novelist Katherine Tynan summed up the main themes as “two strains – God and Ireland, sometimes single, oftener intermingled.” As Plunkett was then prominently involved in Irish politics, Tyan could not resist making the connection: “In a sense, such poetry…bears witness for Sinn Fein. That the singer of these noble numbers should be of the movement is eloquent.”[10]

One could debate the quality of the poems and perhaps compare them unfavourably to that of his eldest son’s, Joseph Mary Plunkett, whose works, such as ‘I See His Blood Upon the Rose’ and ‘I Saw the Sun at Midnight’, are still recited today. George Plunkett’s efforts, on the other hand, have almost entirely receded from public consciousness. As a literary man, his legacy can perhaps be felt through that of Joseph’s, who followed in his father’s footsteps in his ambition to be a poet.

Taste and Scholarship

George did not hoard his talents to himself. From 1883 to 1884, he was editor of the Hibernia, a literary journal with a good deal of, in Tynan’s opinion, “taste and scholarship.” As a budding writer herself, Tynan had contributed a couple of her poems. That the Hibernia, alas, did not last long, Tynan attributed to it being “too bookish” for the philistines of Dublin (she remained friends with Plunkett, with him donating a few books for her shelves, and later sent a cheque for copies of her first publication).[11]

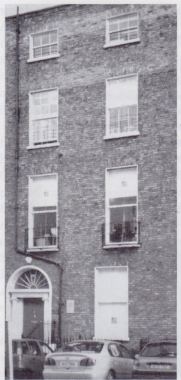

He had by then married his second cousin, Mary Josephine Cranny (who went by her middle name), in 1884. A fruitful union, the couple went on to produce seven children – four girls and three boys. Their two families had worked closely for years, becoming rich in property together. As a sign of how little money was a concern, George and Josephine were set up a year after their wedding in 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin, the residence having been bought, furnished and decorated by the former’s father.[12]

George could be equally generous with others. The nuns of the Little Company of Mary had been asked by Pope Leo XIII in 1883 to set up a centre in Rome. George happened to be there at the time and in a position to assist with the purchasing and refurbishment of the new convent.

He was rewarded a year later with the title of Papal Count. It was, apparently, something of a “source of great embarrassment and annoyance to him… as an ardent Nationalist he did not like being mistaken for some kind of English or Continental aristocrat” (Josephine, on the other hand, was delighted to be addressed as Countess by friends and servants alike). It was not until he was requested by the Vatican to use the title, and from then on, he was Count Plunkett to the world.[13]

That is, at least, according to his daughter Geraldine, who left a memoir that is revealing in its depiction of the Plunkett home life but also problematic due to her naked prejudices. She adored her father and loathed her mother, and it is thus not surprising that her reminisces frequently leaned in favour of one parent at the expense of the other.

For one, Geraldine overlooked how her father was capable of stubborn streaks throughout his life, and it is unlikely that even the Holy Father could have forced him into bearing a title he did not want (he was not above using it for political point-scoring, though – when a rival Nationalist sneered at the title, Plunkett retorted that since it had been awarded by the Pope, any slight on the title was thus a slur against the Vicar of Christ[14]).

Secondly, Geraldine’s depiction of her mother as an insufferable, tight-fisted harridan does not necessarily chime with that of others’. The future Fianna Fáil minister, Todd Andrews, was a regular visitor to the family house after the Civil War, and found the Countess to be “a kind and humorous woman who could laugh at her own oddities.”[15]

But then, Andrews did not have to live with her. George came out of his study one time to find his wife beating their daughter Moya mercilessly with her fists in the hallway, the crime of the wretched girl being to ask her miserly mother to buy her sister Fiona a coat for the winter.

As told by Geraldine, ‘Pa’ Plunkett somehow interpreted the scene as Moya attacking the Countess instead of vice versa, and began thrashing Moya with his walking-stick. Joseph intervened to snatch the stick away and break it over his knee:

Ma took this as a personal insult and redoubled her screaming. Joe comforted Moya while Pa, realising his mistake, stood helplessly patting her on the head to show he was sorry. By the time I came in, Pa had retreated to the study, Ma to the dining-room, and Joe was still trying to comfort poor Moya.[16]

At least Fiona ended up with a new winter-coat after all that.

“You must remember that Mammy is only a little girl,” Plunkett told Geraldine by way of explanation after the latest fight with her mother.[17] An indulgent parent, more a friend than an authority figure to his children, Count Plunkett preferred to avoid household drama – Jane Austen’s Mr Bennett would have understood.

One Missing Plank

One source of drama which Count Plunkett did display an interest in was politics; unfortunately, those already in politics did not reciprocate with an interest in him. He wrote to T.D. Sullivan, the Nationalist Member of Parliament (MP), in 1885, asking to be proposed for the Irish National League of Charles Stewart Parnell, whose words Plunkett quoted about how the national platform lacked but “one plank” – with himself presumably being that missing plank.

If Plunkett had been hoping to ingratiate himself with Parnell’s colleagues, then he was in for a rude awakening. Sullivan’s reply could not have been more condescending. Plunkett, he wrote back, must have taken the line about the plank too literally. “It seems to me,” Sullivan continued, “that if that be so, your joining the League might possibly some day bring disappointment to you, and I would not like to be party thereto.”

The main barrier to Plunkett was his hostility towards the Land League, by then supressed and to which the National League was intended to replace, focusing this time on the issue of Home Rule rather than of land distribution like before. Plunkett’s attitude towards the Land League still rankled with Sullivan: “I can well remember how bitterly opposed you were.”

Academic debates, Sullivan warned, were not enough to win Home Rule – which sums up what he thought of the other man’s style. Also, Home Rule would not be the sole focus of the new League. With the issues of land unresolved and requiring their full attention for the moment, Sullivan took “the liberty of suggesting that you should very well consider your course before ‘casting your lot,’ as the saying is, with the leaders of the National League.”[18]

Although stonewalled from politics, Plunkett could not avoid being affected by the ‘Divorce Crisis’ in 1890, which saw Parnell exposed as an adulterer and a political liability. Most of his allies deserted him, including the caustic T.D. Sullivan; one who did not was George Plunkett.

That the Count would stand by the stricken statesman surprised even the former’s friend, Tynan, who saw him as “one of those trusted Catholic laymen who represented the best and most orthodox Catholic feeling of Dublin” – in other words, a very conventional man. Yet he was prepared to go against the tide when he felt it necessary, a fact that impressed Tynan. Together, they endured the “obloquy, the unjust condemnation, the wrongs”, as she put it, from the Anti-Parnellites (while such words may strike the modern reader as excessively dramatic, events in Mid-Tyrone would show them to be, if anything, understated).[19]

Such unjust obloquy did much to toughen up the Count. In a letter to John Redmond in 1895, Plunkett advised his fellow Parnellite on the best ways to deal with power-brokering clerics such as Dr William Walsh. Redmond was feuding with the Archbishop over stories unflattering to the Church that had appeared in newspapers controlled by the politician. Due to past experience teaching him to “neither fear nor despise the clergy,” Plunkett advised Redmond to moderate such stories, which would hopefully persuade the Archbishop to side with them against their Anti-Parnell rivals.[20]

Such talk sat oddly with his public proofs of piety – in addition to the papal counthood, he amassed an impressive set of papal medals: the Cross of Commander of the Holy Sepulchre, the Grand Cross of Saints Cyril and Methodius, the Cross of the Order of the Advocates of St Peter, and two medals of the Cross of St John of Lateran for him and his wife.[21]

But then, as indicated by his earlier defence of Parnell in the teeth of clerical condemnation – and how his visit to Rome on the eve of the Easter Rising would show – Count Plunkett was quite capable of following his own mind, even where Holy Mother Church was concerned.

Political Pursuits

Plunkett stayed loyal to Parnell to the end, the latter dropping in to see him before leaving for England in 1891. Unfortunately, the Count was out of the house at the time. After waiting for a long while, Parnell left, saying only as he departed: “Perhaps it is just as well.” He died shortly afterwards. Plunkett, who was already upset at having missed Parnell, mourned him deeply.[22]

From then on, the Count took a more active role in politics, albeit with mixed results. In the 1892 general election, he stood as the Parnellite candidate for Mid-Tyrone, the sundered Irish National League no longer able to be quite so fussy in who it took.

That the Parnellite faction could put forward a candidate at all was a surprise. When the news was announced on posters around the town of Omagh, many Anti-Parnellites were inclined to regard it as a joke. It was not until a delegation of Parnellites left Omagh on the evening of the 18th June to greet their incoming candidate that the matter was confirmed.

The Count arrived in town, with a torchlight procession and the sounds of band music, through streets filled with knots of curious onlookers. Plunkett – “who spoke under difficulties,” according to a local newspaper – explained to the crowd his Party’s stance, which was that of the late Parnell, “the policy which his followers over his grave at Glasnevin had pledged themselves to carry out.” Though an outsider, Plunkett busied himself with paying personal visits around the constituency.[23]

The election was to be a three-way contest. According to Geraldine, her father withdrew in order to support his Anti-Parnellite counterpart, Matthew Joseph Kenny, lest he split the Nationalist vote and allow in a Unionist. However, that is untrue, as the parliamentary records show that he continued to stand and received 123 votes, compared to Kenny’s 3,667 and the Unionist candidate’s 2,590. The best that could be said of such a result is that at least Plunkett’s share was too small to have threatened the other Nationalist.[24]

There was nothing that could be said against Plunkett’s courage, however. While making the electioneering rounds by wagon, his party was attacked upon stopping at the Catholic churchyard of Carrickmore by its Anti-Parnellite congregation when their parish priest recognised the rival candidate (it is unclear if the padre had incited the crowd or merely made his hostility known to them). Plunkett was punched in the mouth and, bleeding heavily, hurried back with his companions to their wagon, on which they narrowly escaped amidst a hail of stones.

Little wonder, then, that after the election results were read out on the 8th July, Plunkett praised his fellow loser, the Unionist candidate, as having behaved honourably, while pointedly omitting Kenny and the conduct of his followers.[25]

At least his time there was not to be a complete waste. Three years later, the poet Alice Milligan asked him for the names of Tyrone Nationalists to help gather interest for her politically-themed publications. Literature, art and culture were always there as consolations for Count Plunkett when politics failed.[26]

St Stephen’s Ward

Plunkett picked himself up from this loss to stand again for Parliament in 1895, this time for the St Stephen’s Green Ward, Dublin, which was at least a more plausible seat than faraway Tyrone. He was also better prepared this time, taking care to announce and explain his candidacy in an open letter to the newspapers:

Fellow-Citizens,

Having been selected by a National Convention to contest your division, I gladly accept the task imposed on me.

I am in complete accord with the Independent [Parnellite] Party. I have always held the Policy of Independence of English Parties to be Ireland’s only hope in the Imperial Parliament.

As I do not seek a seat in Parliament as a stepping-stone to office, I will not subordinate the interests of Ireland to any other interest whatsoever.

As a Catholic, I am in favour of Denominational Education.

I am in favour of Peasant Proprietary for Ireland.

I sympathise warmly with the movement for the release of political prisoners,

I will do all in my power for the welfare of the Irish working man, and for the promotion and protection of Irish industries.

It is now our duty to wrest the St Stephen’s Green Division from the Unionist, and to show by our energy and enthusiasm that Ireland is solid for Home Rule.

To secure the result, upon which such vital interests may depend, EVERY HOME RULE VOTE MUST BE POLLED.

Trusting in your tried fidelity to the Old Cause,

I remain, Fellow-Citizens,

Your faithful servant,

GEORGE NOBLE COUNT PLUNKETT[27]

His support for peasant landownership may have come as a surprise to those who had known his aversion towards the Land League. Everything else was standard Nationalist aspiration, particularly the appeal to Home Rule, even if that was very much dead in the water for the while.

This time Count Plunkett was the sole Nationalist candidate, standing against a Unionist, William Kenny (who, by a strange coincidence, shared the same surname as Plunkett’s archenemy in Mid-Tyrone three years ago, although there was no relation). Still, the election was a tense one, with the Irish Times noting that on polling day:

The aspect of Dublin yesterday was unusual. The air was fully charged with political electricity, and for years past the city has not seen busier or more anxious hours than those of the intervals during which the polling booth remained open.[28]

Plunkett and Kenny were seen putting in their fair shares of electioneering work as they drove around to the various polling stations and encouraged their respective adherents throughout the day. Despite the Count’s efforts, Kenny was to be announced as the victor, beating his Nationalist foe by 3,661 votes to 3,205.[29]

Further Attempts

Opportunity knocked again for Plunkett the aspiring politician when, three years later, Kenny was appointed a judge, prompting a by-election for St Stephen’s Ward. Once more, Plunkett was defeated by a Unionist candidate, though the results were closer this time – 3,525 to 3,387.[30]

The cause for this second defeat was attributed by Nationalist critics to a system whereby “lodgers” – the sons of local Unionists – who normally lived in England could stay in their families’ homes in Dublin for a minimum of twelve months to count as lodgers and thus vote in the elections.

Polling day had been notably skittish. Even before the results were known, Plunkettite canvassers were handing out cards objecting to the unfair odds against them. “Notice to Lodger voters take notice,” they read, “That the vote of every person who is registered as a lodger, and who has not signed his claim himself, is objected to, and if necessary, will be objected to on a petition.”

Large placards to the same effect were put up around the constituency. The rebellious mood spread to the polling booths. In Pembroke, a polling clerk made himself conspicuous by pestering ‘lodger’ voters with questions like “What rent do you pay?” Another clerk of Nationalist sympathies attempted to stop a voter on the grounds that he had already left the house for which his name was on the register. The voter, however, insisted on his rights and his contribution to the ballot was duly noted.

The military authorities had caught wind of the tension. To avoid the risk of further unrest, they confined their troops stationed nearby to their barracks for the duration of the poll. Those soldiers entitled to vote were allowed passes to leave on condition that they return at once when done.[31]

Stymied yet again, Plunkett at least had found a cause to work on, and he campaigned for two years to change these rigged electoral procedures. His efforts bore fruit by 1900 when a Nationalist candidate finally took St Stephen’s Ward at 3,429 votes to the Unionist’s 2,873.[32]

The Count had not stood that time. Geraldine attributed his withdrawal from politics to the mutual dislike between him and John Redmond, leader of the reunited Irish Party, not to mention the opposition of his hard-headed wife (who held the purse-strings) to any more expensive elections.[33]

Corroborating this explanation are letters by John Redmond, one from 1896 in which he regretfully – but nonetheless quite firmly – declined to pay for the expenses incurred by Plunkett as part of the unsuccessful election for St Stephen’s Ward the previous year. The Count made one last push for reimbursement in 1902, but received the same rebuff from Redmond, who pleaded money shortages – “It is not a fact I am sorry to say that the National Organisations are well provided with funds” – and ended with how he saw “great difficulty in dealing with the matter satisfactorily to you.”[34]

For all his hard work and money spent, Plunkett had not progressed in the Irish Party from anything higher than a hanger-on. The professional politicians who the Count had aspired to join had had a use for him before, and now, with the Party reunited, they did not.

Cultural Pursuits

Frustrated, Plunkett threw himself into his studies, in particular the writing of a scholarly work on Sandro Botticelli, the Renaissance painter about whom he felt strongly enough to name one of his dogs after. The Renaissance in general was a topic close to his heart; his favourite reading material being, besides the Bible, Dante’s Divine Comedy. When Todd Andrews was invited to inspect the Count’s considerable library, he was too distracted by the “splendid collection” of books on Renaissance art to investigate the rest of the shelves.[35]

Published in 1900, Sandro Botticelli was a success, and earned its author a string of honorary memberships at the Academy of St Luke in Rome, the Academy of the Fine Arts in Florence, and the Pontifical Academy of Fine Arts and Letters of the Virtuosi al Pantheon.[36]

Plunkett went from strength to strength in 1907 when he was made Director of the National Museum. He would regard it as much a calling as a job, and as work in service to the nation. “To my mind a museum is more than a system,” he told a conference of the Museums’ Association in 1912. “It is a part of the national life, it is an expression of the national life and of the higher qualities of the people to whom it belongs.”

One cause for development was that, while the Museum had many ancient objects from Ireland – “We are fortunate in having the greatest collection of Celtic antiquities in Europe,” as he put it – the exhibitions were lacking in later items: “There is the long period during the occupation of Ireland by the English, which is hardly represented at all. We have works of extraordinary beauty extending down as far as the thirteenth century, but then occurs this gap which we have hitherto been unable to fill.” And it was important that this gap in question be filled, “so that our people may be in a position to realise vividly the elements of their own past.”[37]

Equipped with this vision and passion, Plunkett thrived, as did the Museum, such as when he succeeded in dramatically increasing attendance levels from a hundred students in one year to three thousand in another. A theatre room was built, where the Director took the opportunity to mix pleasure with business, and used the venue to deliver lectures of his own.

“To have had lessons on art history from a master such as Count Plunkett does not fall to the lot of many,” was how an appreciative Andrews described his time with him.[38]

He was to remain in that happy role for nine years until the Easter Week of 1916 threw the country into turmoil and uprooted his quiet, orderly life. It was an upset he had had some small hand in.

A Family Affair

By the time of the Rising, the Plunkett family had already been steeped in the sort of politics that Dublin Castle had tried to tempt the Count out of with its National Gallery offer. The clan patriarch was preoccupied with the demands of running his museum (there was no doubt that it was ‘his’), and so it was the new generation who led the charge.

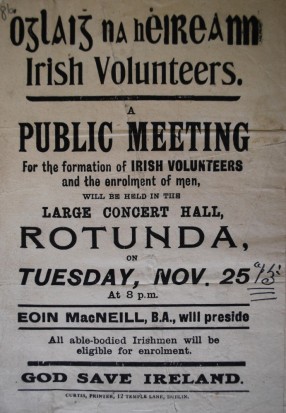

In November 1913, Joseph, saw a notice in certain newspapers, calling a meeting to organise an Irish Volunteer force in order to ensure and, if necessary, fight for the passing of the Home Rule Bill The notice was signed by Eoin MacNeill, co-founder of the Gaelic League.

Joseph was intrigued but, stricken with tuberculosis as he was, not think much of his chances of being accepted, plaintively asking his sister Geraldine: “Do you think I could be of any use? I’m afraid I won’t be able to do very much.”

Geraldine encouraged him to try anyway. After an encouraging talk with MacNeill, Joseph attended the meeting, held on the 25th in a skating rink at the back of the Rotunda Rooms on Parnell Square. Much to his surprise, Joseph found himself on the platform and nominated to the Provisional Committee of the newly-founded Irish Volunteers, under the chairmanship of MacNeill and in the company of other soon-to-be celebrated men such as Patrick Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh.

Joseph returned home excited and not a little confused by his sudden elevation, which Geraldine attributed to his friendships with insiders in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), some of whom were also on the committee. In time, he would be inducted into that oath-bound secret society and, later, its Military Council (which also included Pearse and MacDonagh).

This was despite not being, as his brother Jack admitted, the most practical of people (few in the family were, their mother notwithstanding), his talents instead lying with the suggestion of ideas that others could then implement.[39]

Personal connections also played a role. Joseph had met MacDonagh when the latter was hired in 1909 to tutor him for exams. His resultant low marks did not stop the two from developing a friendship. Both shared literary and poetic tastes, and the pair worked together on the Irish Review magazine, of which MacDonagh was editor. MacDonagh might also have been the one to introduce Joseph to fellow poet Pearse, possibly in 1910 or 1911, making the Military Council sometimes seem like the continuation of the same social circle.[40]

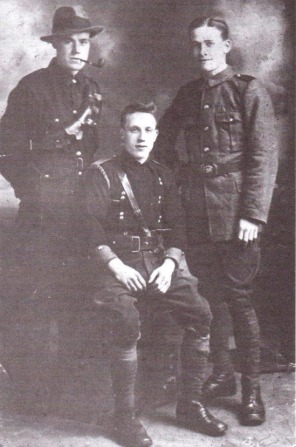

The other Plunkett siblings were not to be left out. Though still a schoolboy, Jack also joined the Volunteers, later working full-time on Joseph’s staff. His main duties were the rigging of wireless radios, at which he admitted to being largely unsuccessful (Jack was still the most technically-minded Plunkett, and in later years would indulge in his hobby of tinkering with motor-car engines).[41]

For her part, Geraldine made to join Cumann na mBan, but was dissuaded by Joseph. Unwilling to risk letters or telephones, her older brother wanted her to relay messengers on his behalf to his co-conspirators, a role which would be easier to perform without attracting the notice of Dublin Castle detectives if she was unknown to them.[42]

Secrecy became the watchword of the day. Jack only learnt years later that he and the third Plunkett brother, George Oliver, had worked on the same project – he could not remember which – despite the two of them living under the same roof. It was not until Easter Week, when the brothers were holed up together in the GPO, that Joseph felt comfortable enough to talk to Jack about certain, previously hush-hush matters.[43]

Larkfield

The family property at Larkfield in Kimmage, south of Dublin, was utilised into a base for the younger Plunketts as they became more involved in radical politics. Consisting of twelve acres of land, with yards, paddocks, an old farm and a mill, complete with a “beautiful middle-sized house…and a garden full of roses,” Larkfield had originally been purchased by the Countess for the family (one of the few times Geraldine was prepared to concede when her mother had not been a complete ogress).

Given the poor state of Joseph’s health, it was easier for his IRB partners to visit him in Larkfield as he had taken to living there along with the rest of the family. Their paterfamilias was the last to join them, and 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street was left to store his books, receive mail but otherwise gather dust. The Count soon settled into a pleasant routine of heading off to the Museum for a day’s work before walking back to Kimmage from the tram at Harold’s Cross.[44]

He was presumably unconcerned about the growing number of young men on the Larkfield property. Unsettled by the threat of conscription, these newcomers had departed from Britain, intending to fight at home for their country rather than in France for another.

“Suddenly one morning about forty young men descended on us,” was how Geraldine remembered the beginning of the ‘Kimmage Garrison’, as they became known by. The numbers of this impromptu company swelled to approximately ninety members, fresh off the boat from cities such as London, Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow.

They were kept busy with military drills in between the manufacture of munitions, namely shotgun pellets and cast-iron grenades. One member proudly recounted how, on a peak night, they could produce up to five thousand lead pellets and twenty grenades, sometimes working twenty-four hour shifts.[45]

Joseph’s work on the Military Council intensified. After Christmas 1915, he told Geraldine that he was off to Germany, which she assumed was for the purpose of procuring weapons. He entrusted his sister with the cipher he would use in any letters sent, to be passed on to her via a cousin and then forwarded to Pearse or another of the conspirators.

He did not trust his mother as much, telling her only that he was leaving for the Continent. In an insight into the complicated dynamics of the household, Joseph changed his mind and informed the Countess that he was going on Volunteer business that might take him to Germany. When Geraldine asked him why “on God’s earth he had done such a thing,” he replied that their mother, adept at prying as she was, would have found out anyway.[46]

Count Plunkett’s involvement, if any, goes unstated in Geraldine’s memoir until early April 1916, when the reader learns of him being sworn into the IRB by Joseph. Geraldine did not record her father’s thoughts on the matter, only that “he was very pleased that his son was now his superior officer.”[47]

But Pa Plunkett was not to be just another ordinary member, for his son had a very particular mission in mind for his new subordinate.

His Holiness

On Easter Sunday, W.J. Brennan-Whitmore was preparing for the start of the uprising in Dublin when he was informed by his commanding officer, Thomas MacDonagh, that Count Plunkett had just returned from Rome, bringing with him the blessing of the Pope for their venture. While pleased to hear such news, Brennan-Whitmore could not help but wonder, just a little, for “it seemed unusual,” and he was still not wholly convinced by the time he penned his memoirs years later.[48]

Brennan-Whitmore was not the only one uncertain, and it was to answer such doubts that Count Plunkett told his side of the story in a brief article for the Irish Press newspaper in 1933:

I have heard that it is denied that I went to Rome immediately before the Rising of 1916 to communicate with His Holiness, Pope Benedict XV. I had no desire to publish information that at the time was not intended for the Press; but now I must disclose certain facts in the interest of truth.

Why he had waited so long before revealing all was left unstated. A need for secrecy seems unlikely, given the length of time that had passed, not to mention how participation in the Rising rapidly became a badge of honour (and political asset) in the months that followed. That the Count had managed for seventeen years to refrain from publicising his role in the most celebrated rebellion in national history – despite the advantages it would have brought to his subsequent career as a Republican firebrand – was an impressive act of restraint in itself.

About three weeks before the Rising, I was, through my son Joseph, commissioned by the Executive of the Irish Volunteers (the Provisional Government) to act as their Envoy on the Continent.[49]

According to Geraldine (whose account fills in some of the gaps in her father’s), Joseph had heard news of the visit of the British Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, to the Vatican. Concerned that His Holiness might be pressured or persuaded to instruct his Irish bishops to condemn any rebellion, Joseph decided that his father would make the best emissary to plead their case. As a papal count, he was, after all, entitled to such an audience.[50]

One task given to me I needed not particular here. When it was carried out, I went onto Rome, according to my instructions.

The task in question was to send a communication to Germany where Sir Roger Casement was attempting to solicit aid for the rebels. The Count was to memorise the message (papers being too vulnerable to carry around) before sending it from neutral Switzerland en route to Italy. Again, it is unclear as to why he felt the need to omit this detail – perhaps he was simply concerned about the length of the article.[51]

Having arrived at his destination, the Count was granted his audience with Pope Benedict:

For nigh on two hours we discussed freely the question of the coming struggle for Irish independence. The Pope was much moved when I disclosed the fact that the date for the Rising was fixed and the reason for that decision. Finally, I stated that the Volunteer Executive pledged the Republic to fidelity to the Holy See and the interests of religion. Then the Pope conferred His Apostolic Benediction on the men who were facing death for Ireland’s liberty.

The wording makes it sound as if Plunkett was handing the country over on a silver platter. Most likely, he was reassuring the Pope that the insurgents had no distastefully left-leaning, anti-clerical or – God forbid – socialist tendencies.

(Such consideration for papal sensitivity was not untypical. Four years later, Sean T. O’Kelly stressed to the same pontiff that “as practising Catholics we have never allowed our national movement for independence to be contaminated by anti-religious or other dangerous movements condemned by the Church.”[52])

The article also gives the impression that the Pope took all of this in with serene acceptance. Plunkett gave a more dramatic version to Geraldine, in which the Vicar of Christ bestowed his blessing with tears of sympathy pouring down his face.[53]

Monsignor Curran’s record of what the Count had told him on Easter Monday was less striking but perhaps more likely. Here, Benedict XV comes across as noticeably circumspect upon being asked to approve of a venture that had just been sprung on him:

The Pope showed great perturbation and asked was there no peaceful way out of the difficulty…Count Plunkett answered every question, making it plain that it was the will of the leaders of the movement to act entirely with the good-will or approval – I forget which now – of the Pope and to give an assurance that they wished to act as Catholics. It was for that reason they came to inform his Holiness. All the Pope could do was express his profound anxiety.[54]

One consistent detail in the different versions is how Plunkett informed the Pope that the date of the uprising was fixed, leaving the latter with no chance at dissuasion. It was the same Machiavellian deference he would apply when dropping in to see Archbishop Walsh. The Count may have been a man of a lofty intellect and cultured tastes, but he was also capable of low cunning when it was called for.

The Rising

Count Plunkett finished his article with his return to Ireland, just in time for the big event:

Back in Dublin on Good Friday, 1916, I sent in my report on the results of my mission to the Provisional Government. In the General Post Office, when the fight began, I saw again the portion of that paper relating to my audience with His Holiness in 1916.

According to Geraldine, her father arrived back in Ireland on Holy Thursday and spent the remaining four days before the Rising travelling around the country to meet with various bishops to request that they also refrain from condemnation. Geraldine thought he visited five bishops altogether, but Monsignor Curran was not aware of any of this when he saw the Count on Easter Monday, and it is hard to believe that these other bishops would not have passed word to the Archbishop of Dublin beforehand.

Count Plunkett omitted his talk with Curran in his 1933 article and also how afterwards, according to Geraldine, he had made his way to the GPO, with the Rising unfolding all around, to ask Joseph to take him on as another Volunteer. Recognising that a 65-year old man did not make for an credible soldier, Joseph told his father that they had enough men inside already and instead sent him home.[55]

In the meantime, the members of the ‘Kimmage Garrison’ had been preparing themselves. Pearse had addressed them a week before, urging them to be ready. His enthusiasm was infectious and the men looked forward to Easter Sunday when they would finally see action.

When Sunday came, the ‘Garrison’ was assembled and armed when a car pulled up at Larkfield with the news that the operation was cancelled.

The following day saw the men in a sullen mood. Before, they had been early risers to a man but now they did nothing but lounge about. The only flicker of interest was in the talk of heading into town to start their own insurrection, orders and countermands be damned.

It was sometime before noon when a whistle blew, calling the ‘Garrison’ into line. George Oliver Plunkett, the 22-year old younger brother of Joseph, had been placed in charge – no one seemed perturbed by such nepotism – and was now wearing, according to one of his subordinates, “a broad, proud, confident smile.”[56]

George read out a dispatch, saying they were to parade at Liberty Hall. To the men, this could mean only one thing: they would have their Rising after all. Enthusiasm overrode discipline as they broke ranks and ran to gather their weapons.

Now prepared, the Volunteers marched to where they boarded a tram (their fares paid for by a considerate George) and were taken to the city centre, where they disembarked at O’Connell Street. Making their way to Liberty Hall, they saw Joseph waiting for them outside. He was, as one of them recalled, “beautifully dressed, having high tan boots, spurs, pince-nez and looked like any British brass hat staff officer.”[57]

Family Matters

It had been a turbulent few days for Joseph as he tried balancing the imminent rebellion with his love life. His fiancée, Grace Gifford, remembered him in high spirits the previous week. Things took a darker turn on the Saturday when Michael Collins visited her at home to deliver, on Joseph’s behalf, a revolver and money, one to fight with and the other to bribe a British soldier if needs be. Grace did not know of which to be more frightened.

When she saw her betrothed the next day, he was “wretched looking”, having skipped the nursing home he was due to check into. Afterwards, Grace could not recall what they had talked about, not even if it was about their wedding, for they were due at the altar the next day, alongside his sister Geraldine and her nuptials in the same church.

Grace and he had been discussing marriage dates for some time. Joseph had suggested Lent which Grace, as a newly converted Catholic, was against. She suggested Easter instead, but Joseph at first resisted on the grounds that “we may be having a revolution then.”[58]

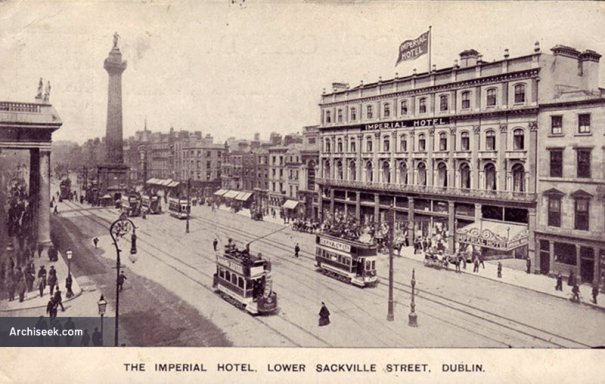

Though Grace and Joseph would not have their wedding until they were in a prison cell, hours before the latter was due to be executed, Geraldine plunged ahead with her own on Easter Sunday. The happy couple cycled to the Imperial Hotel on Sackville (now O’Connell) Street for the night.

The following morning, Geraldine watched from the hotel window with her new husband as uniformed Volunteers advanced up the street and halted in front of the GPO. She recognised her brothers, Joseph and George, the older accompanied by his aide-de-camp Michael Collins, as they and their men set to work constructing barricades.

One Volunteer tried to drive an abandoned tram into another but failed to pick up the necessary speed. Instead, Joseph threw a Larkfield-made bomb into the vehicle and shot it with his pistol from about thirty yards away – “a beautiful shot,” as Geraldine remembered. The shot detonated the bomb, mangling the tram and rendering it a perfect obstacle.

This was the last time Geraldine would see her brother. When she tried talking her way into the GPO, she was told on behalf of Joseph to go home as the building was already full up. It was the same line Joseph gave his father. He may have been willing to risk his own life but he drew a line at certain family members.[59]

Prison

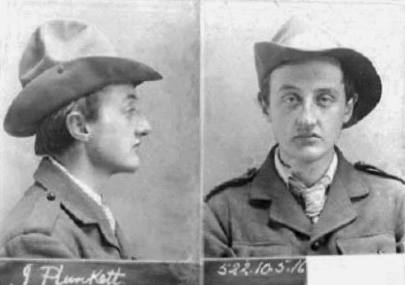

Count Plunkett was arrested on the 1st May, two days after the collapse of the Rising. His experiences were described in two short documents: a pencil manuscript in the Count’s hand in the first person, and a typescript in the third, possibly intended for publication.

The Count was in his Upper Fitzwilliam Street residence when a body of soldiers demanded admittance. Despite their lack of a warrant, Plunkett decided that compliance was the wisest course. The men searched the house, breaking open desks and spilling their contents onto the floor, while taking the opportunity to pocket a number of items, including the Count’s prized collection of papal medals.

Also seized were two historical dress-swords which the Count had labelled for loan to the Museum. Plunkett was unaware of these thefts at the time as the only item officially taken was a third ceremonial sword that came with his uniform as Director. The soldiers also tried to get him to admit to having guns in the house but he insisted there was none.

Their search complete, the soldiers arrested Plunkett and took him in an iron-sided van to Dublin Castle. There, he was brought to a small, dirty cell, occupied by twenty others, where they spent the night. His roommates were a mixed bunch, some being “men of education” like himself, others having been arrested for looting. A few were injured, indicating that they had played a part in the recent fighting.

“I cannot” – at this point, the manuscript broke off. The typescript continued the unhappy narration. After a breakfast of canned ‘bully beef’, stale biscuits and tea served in cans, the prisoners were ordered out and marched through the streets to Richmond Barracks, “being subject to insult by the military and the disreputable camp-followers on the way.”

Upon reaching the Barracks, they were again crammed, twenty-seven of them, into a space intended for eleven. As before, their confinements were filthy despite the presence of wounded men who received no special consideration (one fellow prisoner who shared the cell with Plunkett corroborated the crowded squalor of their confinement, and how the prisoners discovered that a pair of boots could make a much-welcomed pillow[60]).

For nearly a week, the prisoners were left to sleep on bare floorboards. Sometimes it was so cold that even the weariest were kept awake through the night. Mealtimes were a drudge of hard biscuits, ‘bully beef’ and black tea, assuaged only when the guards were bribed for food from outside. The Count – or least the document – made the claim that he broke three teeth on a biscuit, but as this is mentioned nowhere else, it was probably untrue.

Things improved somewhat when their treatment was publicised in the newspapers, and the medical staff warned of a fever outbreak should conditions remain as they were. The prisoners were first given rugs to lie on. Sanitary arrangements improved. Food became at least tolerable.

After a fortnight, the Count was finally granted a bed; a hard one, but better than the floorboards. He began receiving visits from his family except his wife, who had been arrested in turn two days after him, a fact he had been previously unaware of.

Twice he was taken to Kilmainham Jail and brought out to the grounds where a court-martial had been convened, apparently for a session, but each time he was sent back, still untried. At least such outings allowed him to see Joseph, George and Jack, also waiting as prisoners. A soldier later said within earshot that all three had been shot. Another clarified a few days later that George and Jack had ‘only’ been sentenced to ten years. All their father could glimpse of the pair was from a window before they were dispatched to Portland Prison in England.[61]

He had already witnessed his eldest son on the day of Joseph’s court-martial, standing in the square of Richmond Barracks, from a first storey window. The two looked at each other for a long while before Joseph was moved on, soon to be before a firing-squad. The Count was weeping as he told this to Geraldine: “Even after the executions, it was not thought right to weep openly, but Pa did, and it was one of the reasons I loved him.”[62]

Visitors’ Hours

For all the hardship, Count Plunkett did his best to stay in good humour. A friendly priest, Father Eugene Nevin, visited him in Kilmainham, finding the “dear old man in a small white-washed room, the only furniture of any kind being what looked like a large soap box on which he sat reading the last evening’s Mail.”

Not only could Plunkett greet his visitor with a smile, but he was soon laughing out loud, finding much merriment in the published correspondence between the Bishop of Limerick, Dr Edward O’Dwyer, and General Maxwell. Bishop O’Dwyer had replied to Maxwell’s requests for cooperation with a notably acerbic pen, and Plunkett could at least vicariously enjoy the Bishop’s defiance of the man who had overseen Joseph’s execution two weeks before.[63]

Another source of humour, albeit of a black kind, was a piece of pantomime by him and his fellow prisoners. Plunkett played the role of judge in a mock-trial of Éamon de Valera, awaiting his own court-martial in Kilmainham, who was ‘charged’ with conspiring to become King of the Periwinkles and Emperor of the Muglins.

Everyone present would have known of similar ‘trials’ performed by the imprisoned Young Irelanders after their own failed uprising almost seventy years before. Despite the intent of the charade to relieve some of the tension, de Valera could not help but be unsettled, particularly when the onlookers took the game a little too far by clapping their hands to imitate the sound of a firing squad.[64]

But such diversions could not hold off the reality of the situation indefinitely. When Geraldine was able to visit her father on the 8th May, a week after his arrest, she was shocked by what she saw:

We were taken upstairs to a guardroom where Pa was alone, sitting on the bed. I hardly recognised him. He had been arrested more than a fortnight before and was extremely dirty and miserable and more pleased to see the soap and towel than the food. His beard had practically all fallen off and although he was only sixty-five, he looked eighty-five, a poor tired old man.[65]

Under such conditions, it is unsurprising that his attempts at poetry, composed on scraps of paper and spare envelopes, should have a suitably anguished tone:

My foes are many, my friends are but few,

But who can measure my joy in my treasure,

My God, my Heaven, by baby Jesú,

O sleep, sleep deep, my joy, my treasure,

O sleep, my baby, my baby Jesú.[66]

The Countess was having it no better. Another woman imprisoned at Mountjoy in the cell next to Josephine’s remembered her being “in a terrible state about her son having been executed, and she used to get awfully lonely and upset at night.” Talking to each other through the wall brought at least a measure of comfort.[67]

Exile

Relief came for the pair when they were both notified on the 5th June that they could be released on condition of signing a form, agreeing to deportation to a place in England of their choice. Both signed, with Oxfordshire decided as their destination. They were reunited at Upper Fitzwilliam Street and spent four days there before leaving the country on the 9th, taking their daughter Fiona with them.

As part of their agreement, the couple promised to “abstain from making any speeches or attending or taking part, directly or indirectly, in any political or other demonstration or meeting before leaving Ireland.” They also agreed not to return home without written permission from the Home Secretary or the military authorities.[68]

Exactly why either of them had been arrested at all is unclear. Unlike their sons, they had not been arrested at the scene of an armed uprising. Neither had held leadership positions or any rank among the Irish Volunteers. The lack of a court-martial or trial means that whatever evidence the authorities had against the couple, as well the reasons for detaining two aging non-combatants in the first place, will remain unknown.

The exiles arrived in London on the morning of the 10th before pressing on to Oxford. Count Plunkett attended Mass the following day before getting down to business and writing to the Prime Minister and later the Home Secretary to ask for a meeting (there is no indication that either replied, however).

Always ready to balance politics with his craft, he sent copies of some verse to a number of Irish publications. Hinting at his state of mind was the title of one: ‘O Blessed Gift of Poverty’.[69]

While their Oxford lodgings were a far cry from the luxurious residence on Upper Fitzwilliam Street or the idyllic surroundings of Larkfield, materially the couple could have been worse. A natural entrepreneur, the Countess crafted furniture to sell and, though Geraldine snidely commented on their quality in her memoirs, she made enough to cover the rent and shopping (the latter task falling to Fiona). For home fires, the family made do with old newspapers and lumps of sugar.[70]

Still, the future looked bleak. They were to be dispossessed for an indefinite period, many of their belongings in Dublin had been stolen, and their eldest son was dead with the other two were about to embark on lengthy penal sentences. The National Museum lay over a burnt bridge, the Count having received notice of his suspension as its director. His position would “be determined upon the receipt of a Report from the Military Authorities,” which made any chance of reclamation an unlikely one.[71]

As if to rub salt into the wounds, Count Plunkett, who had chosen Oxford for access to its famous Bodleian Library, had his application for a library ticket refused.[72]

Continued in: Plunkett’s Turbulence: Count Plunkett and his Return to Ireland, 1917 (Part II)

References

[1] Curran, M. (BMH / WS 687), pp. 53-55

[2] O’Shiel, Kevin (BMH / WS 1770 – Part V) p. 7

[3] Plunkett Dillon, Geraldine (edited by O Brolchain, Honor) In the Blood: A Memoir of the Plunkett family, the 1916 Rising, and the War of Independence (Dublin: A. & A. Farmar Ltd, 2006), p. 210

[4] O’Brien, William (BMH / WS 1776), p. 108

[5] Catholic Bulletin, Vol. VII, No. 1, January 1917, p. 53

[6] Laffan, Moira. Count Plunkett and his Times (1992), p. 77

[7] Andrews, C.S. Man of No Property (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001), p. 43

[8] Plunkett, G.N. God’s Chosen Festival (A Christmas Song) and Other Poems (Dublin: John Mullany, 1877), p. 41

[9] Ibid, p. 55

[10] Studies: an Irish Quarterly Review (1921) Vol. X, No. 40, p. 662

[11] Tynan, Katharine. Twenty-Five Years: Reminisces (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1913), pp. 128, 167

[12] Laffan, pp. 7-9

[13] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 22, 30

[14] Tyrone Constitution, 08/07/1892

[15] Andrews, p. 49

[16] Plunkett Dillon, p. 125

[17] Ibid, 96

[18] Count Plunkett Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), MS 11,374/3/7

[19] Tynan, p. 383

[20] Count Plunkett Papers, National Library of Ireland (NLI), MS 11,376/1/9

[21] NLI, MS 11,381/4/2

[22] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 32-3

[23] Tyrone Constitution, 01/07/1892

[24] Plunkett Dillon, p. 33 ; Walker, Brian M. (ed.) Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, 1801-1922 (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1978), p. 149

[25] Tyrone Constitution, 15/07/1892

[26] NLI, MS 11,374/7/2

[27] Irish Times, 08/07/1895

[28] Ibid, 17/07/1895

[29] Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, p. 153

[30] Ibid, p. 157

[31] Irish Times, 22/01/1898

[32] Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, p. 160

[33] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 34-35

[34] NLI, MS 11,374/7/6, MS 11,374/9/4

[35] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 31, 60 ; Andrews, p. 42

[36] Catholic Bulletin, Vol. VII, No. 1, January 1917

[37] Irish Monthly, Vol. XL, pp. 608-12, November 1912

[38] Laffan, p. 13 ; Catholic Bulletin, Vol. VII, No. 1, January 1917, p. 56 ; Andrews, p. 43

[39] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 153-4 ; Plunkett, Jack (BMH / WS 488), pp. 2-3

[40] Plunkett, Jack, p. 2

[41] Plunkett, Jack, p. 12 ; Andrews, p. 42

[42] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 155-6

[43] Plunkett, Jack, pp. 20, 32

[44] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 151, 188, 201

[45] Ibid, p. 100 ; Good, Joseph (BMH / WS 388), pp. 5-6, 8

[46] Plunkett Dillon, p. 176

[47] Ibid, p. 211

[48] Brennan-Whitmore, W.J. (introduction and notes by Travers, Pauric) Dublin Burning: The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1996), p. 29

[49] Irish Press, 26/05/1933

[50] Plunkett Dillon, p. 211

[51] Ibid

[52] ‘Memorandum by Sean T. O’Ceallaigh to Pope Benedict XV’, 18/05/1920, Documents on Irish Foreign Policy, http://www.difp.ie/docs/1920/Appeal-to-Vatican/35.htm (Accessed 21/02/2017)

[53] Plunkett Dillon, p. 211

[54] Curran, p. 54

[55] Plunkett Dillon, p. 227

[56] Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 156), p. 14

[57] Good, pp. 7-8

[58] Plunkett, Grace, (BMH / WS 257, pp. 7-10

[59] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 222-3, 226

[60] Daly, Seamus (BMH / WS 360), p. 56

[61] NLI, MS 11,381/4/2, MS 11,381/4/3

[62] Plunkett Dillon, p. 238

[63] Nevin, Eugene (BMH / WS 1605), p. 53

[64] Coogan, Tim Pat. De Valera – Long Fellow, Long Shadow (London: Random House, 1993), p. 76

[65] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 237-8

[66] NLI, MS 11,399

[67] Ibid, MS 11,381/4/1 ; Lynn, Kathleen (BMH / WS 357), p. 11

[68] NLI, MS 11,381/6/1

[69] NLI, MS 11,381/4/3

[70] Plunkett Dillon, pp. 251-2

[71] NLI, MS 11,374/14/3

[72] Plunkett Dillion, pp. 246, 252

Bibliography

Bureau of Military Statements

Curran, M., WS 687

Daly, Seamus, WS 360

Good, Joseph, WS 388

Lynn, Kathleen, WS 357

Nevin, Eugene, WS 1605

O’Brien, William, WS 1776

O’Shiel, Kevin, WS 1770

Plunkett, Grace, WS 257

Plunkett, Jack, WS 488

Robinson, Séumas, WS 156

Books

Andrews, C.S. Man of No Property (Dublin: The Lilliput Press, 2001)

Brennan-Whitmore, W.J. (introduction and notes by Travers, Pauric) Dublin Burning: The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1996)

Coogan, Tim Pat. De Valera – Long Fellow, Long Shadow (London: Random House, 1993)

Laffan, Moira. Count Plunkett and his Times (1992)

Plunkett, G.N. God’s Chosen Festival (A Christmas Song) and Other Poems (Dublin: John Mullany, 1877)

Plunkett Dillon, Geraldine (edited by O Brolchain, Honor) In the Blood: A Memoir of the Plunkett family, the 1916 Rising, and the War of Independence (Dublin: A. & A. Farmar Ltd, 2006)

Tynan, Katharine. Twenty-Five Years: Reminisces (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1913)

Walker, Brian M. (ed.) Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, 1801-1922 (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1978)

National Library of Ireland Collection

Count Plunkett Papers

Newspapers

Freeman’s Journal

Irish Press

Irish Times

Tyrone Constitution

Journals

Catholic Bulletin

Irish Monthly

Studies: an Irish Quarterly Review

Online Source

Documents on Irish Foreign Policy