In the Interests of the Country

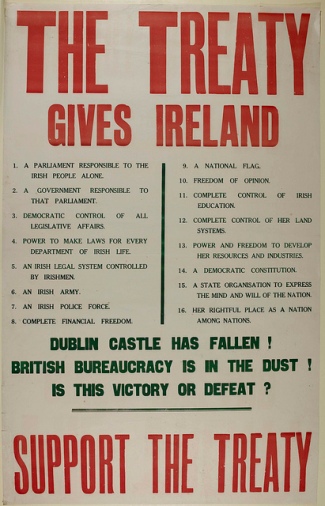

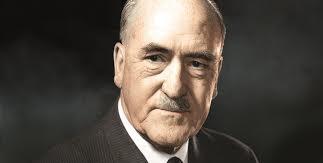

Seán Mac Eoin’s speech to the Dáil on the 19th December 1921 was notable in how brisk and business-like it was. The TD for Longford-Westmeath opened by seconding the motion by Arthur Griffith – the speaker proceeding him – that called for the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the item under discussion in the chamber.

As for the whys, Mac Eoin explained where his priorities lay:

I take this course because I know I am doing it in the interests of my country, which I love. To me symbols, recognitions, shadows, have very little meaning. What I want, what the people of Ireland want, is not shadows but substances, and I hold that this Treaty between the two nations gives us not shadows but real substances.[1]

As a soldier through and through, Mac Eoin focused on the military aspects of this substance. That he was not an orator was evident, as he halted more than once while talking, but he made an impression all the same to his viewers:

Clean-shaven, sturdily-built, wearing a soft collar, his pure, rich voice sounded like a whiff of fresh country air through the assembly. His hands were sunk into the pockets of his plain tweed suit.

For the first time in seven hundred years, Mac Eoin reminded his audience in his “pure, rich voice”, British forces were set to leave Ireland, making way for the formation of an Irish army, and a fully equipped one at that.[2]

This was what he and his comrades had been fighting for, to the extent that even if the Treaty was as bad as others said or worse, he would still accept it. After all, should England in the future prove not to be faithful to Ireland, then Ireland could still rely on its armed forces if nothing else (Mac Eoin was clearly a believer in the ‘good fences make good neighbours’ maxim).

An Extremist Speaks

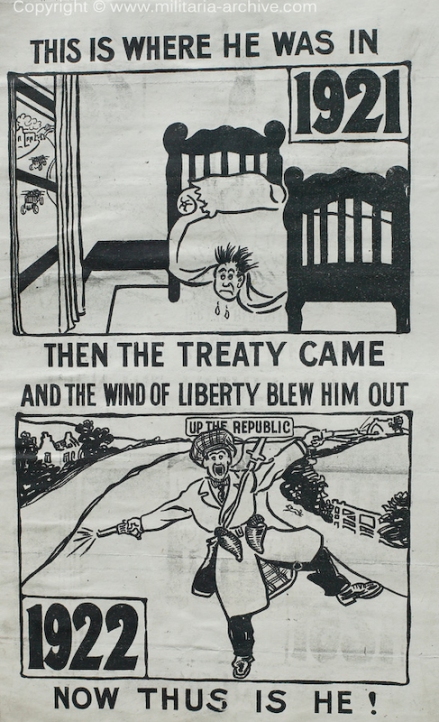

Mac Eoin acknowledged that it might appear strange that someone considered an extremist like him should be in favour of a compromise:

Yes, to the world and to Ireland I say I am an extremist, but it means that I have an extreme love of my country. It was love of my country that made me and every other Irishman take up arms to defend her. It was love of my country that made me ready, and every other Irishman ready, to die for her if necessary.[3]

Mac Eoin wrapped up his speech with what would become the rallying cry of the pro-Treaty side: the agreement meant the freedom to make Ireland free. It was not the most eloquent of oratory on display that day, perhaps showing the haste in which it had been written on the tramcar to the National University where the debates were held.[4]

Nonetheless, it got across the essential points, and some of his statements lingered on afterwards in the minds of his listeners.[5]

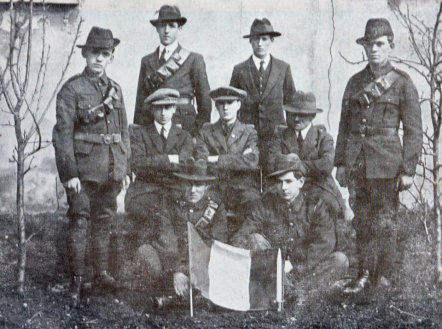

Besides, what he said was perhaps less important than who he was. The reporter for the Irish Times certainly thought so, remarking on his reputation as a fighter par excellence and how his support alone would have an impact on the younger, more martial-minded members of the Dáil. As an experienced combatant, having earned renown as O/C of the North Longford Flying Column, while still only twenty-eight years old, Mac Eoin was one of their own, after all.[6]

‘Red with Anger’

For the remainder of the debates, Mac Eoin kept his cool, refraining from the indulgence of interruptions, point-scoring and lengthy, out-of-turn discourses that characterised much of the subsequent exchanges.

When Seán T. O’Kelly, representing Dublin Mid, referred to “those who put Commandant Mac Eoin in the false position of seconding” the motion for the Treaty ratification, Mac Eoin asserted himself calmly: “Who did so? I wish to say that I seconded the motion of my own free will and according to my own free reason.”

“Well, I accept the correction with pleasure,” O’Kelly replied frostily.[7]

Still, there were moments when Mac Eoin could be roused, such as when Kathleen O’Callaghan, the TD for Limerick City-Limerick East, made a backhanded compliment about military discipline. Certain speakers, she noted, each with an Army background, had used the exact same three or four arguments with what were practically the same words.

Although O’Callaghan insisted (not wholly convincingly) this was meant as a compliment and not as an insult, Mac Eoin – clearly one of the speakers referred to – was tetchy enough to retort that since every officer in the army had the same facts before him, it was only natural that they would come to the same conclusions and make the same arguments.[8]

Another display of emotion was when Cathal Brugha, in one of the more memorable monologues of the debates, launched a vitriolic attack on the character and record of Michael Collins. Mac Eoin, “red with anger”, according to the Irish Times, was among those who sprang to their feet in outrage at the treatment of their beloved leader.[9]

That Gang of Mine

Those in the debating chambers were not the only critics with whom Mac Eoin had to contend. On the same day as his speech, he received a letter from Dan Breen, who had likewise achieved fame for his exploits in the past war. Breen took umbrage at the other man’s argument that the Treaty was bringing the freedom for which they and their comrades had fought. As one of his said comrades, Breen wrote with a snarl, he “would never have handled a gun, nor fired a shot, nor asked anyone else, living or dead, to do likewise if it meant the Treaty as a result.”

The word ‘dead’ had been underlined in the letter. In case Mac Eoin was wondering as to the significance of that, Breen pointedly reminded him that today was the second anniversary of the death of Martin Savage, killed in the attempted assassination of Lord French. Did Mac Eoin suppose, Breen asked sarcastically, that Savage had given his life trying to kill one Governor-General merely to make room for another?[10]

Breen warned that copies of this letter had been sent also to the press. He was to go as far as reprint it in his memoirs. Mac Eoin’s remarks had evidently cut very deeply indeed.[11]

Writing more in sorrow (and bewilderment) then in anger was Séamus Ó Seirdain. An old friend from Longford and a war comrade, he was writing from Wisconsin in the early months of 1922 for news from the Old Country, particularly in regards to the Treaty, over which he had the gravest of doubts. “A man may be a traitor and not know it,” he mused, though he hastened to add that he did not consider Mac Eoin a traitor any more than St. Patrick was a Black-and-Tan.

He was not writing for the purpose of hurting anyone, he assured Mac Eoin, only reaching out “to an old friend who has dared and suffered much for the cause and who may inform me as to what the mysterious present means.”

Only One Army

When Mac Eoin wrote back in April 1922, he assured Ó Seirdain that everything was righting itself by the day. True, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was still divided to some degree but it would pull itself together in the course of a few weeks. It had, after all, taken an oath, one to the Republic, and it would never take another, Mac Eoin wrote. There would be no Free State Army. There would only be the IRA until its ideal was achieved and then there would only be the Irish Army.

Arguing for the tangible benefits of the Treaty, Mac Eoin pointed out that there were now more arms in Ireland and more men being trained in the use of them than at any other point in the country’s history. All their posts and military positions once occupied by Britain were in Irish hands. Reiterating much of what he had told the Dáil, by developing the Army (as well as the economy – a rare acknowledgment by Mac Eoin of something non-military) Ireland would be in the position to tell Britain where to go if it came to it.

Although Mac Eoin did not feel the need to be ostentatiously hostile to all things political like some others, he dismissed opponents of the Treaty as “jealous minded politicians…nursing their wounded vanity” while shouting the loudest about patriotism and freedom. If he had anyone in mind specifically, he left that unstated.[12]

By September 1922, three months into the Civil War, it was an embittered Ó Seirdain who wrote to his old friend, denouncing the Free State and the “British-controlled” media in the United States that endorsed it. But if Ó Seirdain was unconvinced by Mac Eoin’s previous arguments in defence of the Treaty, he did not let it get personal, having said a Mass for both Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, both of whom he considered as tragic a loss as Harry Boland and Cathal Brugha on the other side.

As for Mac Eoin: “I know that you are in good faith, I know that your heart is true as ever, but I cannot understand why you are with the Free State. I may never hear from you again, and I want you to understand that no matter what you may think of me, I still stick to the old ideal, and I am still your friend.”[13]

Machinations

He may have castigated the oppositions as petty politicians but Mac Eoin, both publicly and behind the scenes, had helped spearhead much of the political manoeuvrings in the build-up to the fateful Treaty.

On the 26th August 1921, four months before the agreement was signed, Mac Eoin had been the one to propose to the Dáil the re-election of Éamon de Valera as President of the Irish Republic. Inside the Mansion House, Dublin, so packed with spectators that every available seat and standing room had been taken long before the Dáil opened, Mac Eoin praised de Valera as one who had already done so much for Irish freedom: “The honour and interests of the Nation were alike safe in his hands.”[14]

The Minister for Defence, Richard Mulcahy, seconded the motion right on cue, and de Valera was set to resume his presidency. This was, of course, a carefully choreographed performance, and Mac Eoin later wrote of how he had been acting on the direction of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).[15]

As a member of the IRB Supreme Council, Mac Eoin had boundless faith in the good intentions of the fraternity, which he defended long after it had ceased to exist. For Mac Eoin, the secret society had been the critical link between the days of revolution and the new dawn of a free, democratic country.

Not that everyone would have agreed with this glowing assessment, particularly about Mac Eoin’s later contentions that de Valera had merely been the ‘public’ head of the Republic, with the IRB remaining the true government of the Republic until February 1922, when the Supreme Council agreed to transfer its authority to the new state.[16]

The Army of the Republic

Before then, de Valera, as Mac Eoin saw – or, at least, chose to see it – had been no more than a convenient figurehead:

At the time of the Truce, Collins was President of the Supreme Council of the IRB and thus President of the Republic. After the Truce, de Valera had journeyed to London and spoke with Lloyd George and each day he sent a report back to Collins: that was because he knew that Collins was the real President, although that was still secret.[17]

The idea of the high and mighty de Valera answering to Collins like a dutiful servant may have been no more than a pleasing fantasy of Mac Eoin’s, who was never to entirely reconcile himself to how the Anti-Treatyites went on to dominate Irish politics in the form of Fianna Fáil. But, with the amount of genuine machinations going on behind the scenes, perhaps Seán T. O’Kelly and Kathleen O’Callaghan were not so unreasonable in their suspicions, after all.

Not so easily managed was the widening breach between the pro and anti-Treaty sides. When it came for the Dáil to count the votes on the 7th January 1922, it had been agreed by 64 to 57 to ratify the Treaty. Almost instantly, the issue was raised as to whether it would be a peacefully accepted decision.

“Do I understand that discipline is going to be maintained in Cork as well as everywhere else?” asked J.J. Walsh, the TD for the city in question, a trifle nervously.

“When has the Army in Cork ever shown lack of discipline?” responded Seán Moylan, the representative of North Cork, to general applause.

As Minister of Defence, Richard Mulcahy hastened to reassure the Dáil. “The Army will remain occupying the same position with regard to this Government of the Republic,” he said, adding confidently: “The Army will remain the Army of the Irish Republic.”[18]

This was met with applause, but Mac Eoin would criticise what he saw as Mulcahy’s presumption. “I don’t think that was a wise thing to say,” he told historian Calton Younger years afterwards. “It was not a Government decision. He was giving it as his own.”[19]

For Mac Eoin, keeping to such distinctions would be critical if the fledgling nation was to survive as old certainties collapsed and loyalties blurred.

Securing Athlone

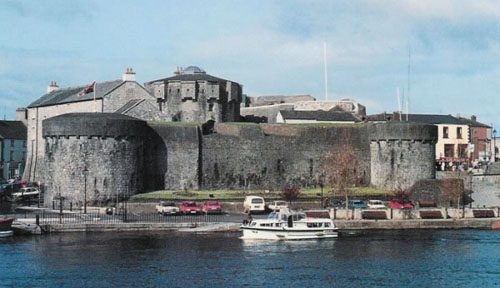

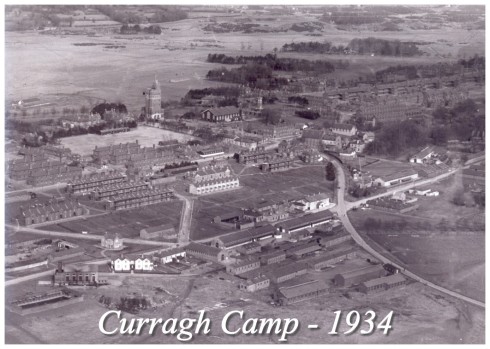

Still, for a while, it would seem as if Mulcahy’s assurance of an intact IRA would prove true. Now a Major-General, Mac Eoin was tasked with supervising the handover of Athlone by the departing British Army, as per the terms of the Truce, on the 28th February 1922.

Thousands had gathered in Athlone for that historic day, lining the streets from the barrack gates to Church Street. The Castle square was likewise packed with people, young and old, trying to force their way to the front, many having come from miles around. Close to a hundred Irish soldiers had arrived the day before from Dublin and Longford, and had been met at the station by their comrades in the Athlone Brigade, who had taken up position on the platform and saluted the newcomers.

Their presence had already attracted the attention of a large crowd, complete with torchbearers and a brass-and-reed band. The new soldiers marched into the town, amidst scenes of ample enthusiasm, to the Union Barracks, before billeting in nearby hotels. Mac Eoin’s arrival later that evening in a car was low-key in comparison.

The following morning, the British garrison began departing in small detachments, while large companies of their Irish counterparts, and now successors, moved in from the opposite direction. The two armies met each other on the town bridge, the brass-and reed-band stopping in its rendition of God Save Ireland and the officer at the head of the IRA column giving his men the order to ‘left incline’ to allow the British sufficient space to pass by.

The IRA resumed their journey while the band continued with Let Erin Remember the Days of Old. Tumultuous cheering greeted the Irishmen as they crossed the bridge to where the gates of the barracks were open to receive them. The last of the previous garrison still present, Colonel Hare, joined Major-General Mac Eoin as they entered the interior square and into the building headquarters.

After a few minutes, both men reappeared. Mac Eoin gave the orders ‘attention’ and ‘present arms’ to his arrayed soldiers who promptly obeyed. Colonel Hare returned the salute and was escorted by Mac Eoin to the gate. The two shook hands and with that, Colonel Hare and the last of a foreign presence departed from Athlone Barracks.

The First Glorious Day

Given the press of people outside, the gates were closed, not without difficulty, to prevent the crowds from pouring in. The troops were paraded in the square before Mac Eoin, and only then were the gates reopened and the general public allowed in, where they were formed up at the rear of the uniformed ranks.

“Fellow soldiers and citizens of Athlone and the Midlands,” said Mac Eoin, standing in a motorcar in the centre of the square, “this is a day for Athlone and a day for the Midlands. It is a day for Ireland, the first one glorious day in over three hundred years.”

Look how we have regarded Athlone. Athlone had all our hatred and our joys and we looked on it with pride. We had hatred for Athlone because it represented the symbols of British rule and the might of Britain’s armed battalions. Thank God the day has come when I, as your representative, presented arms to the last British soldier and let him walk out of the gate – in other words – he skipped it!

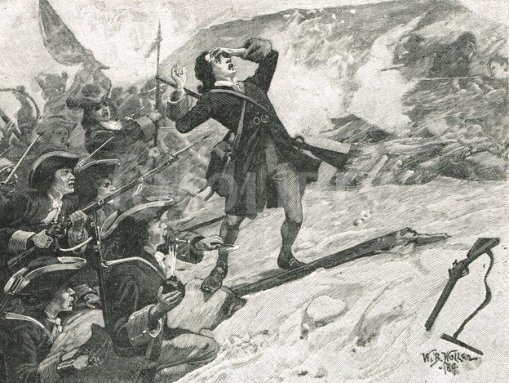

This was met with appreciative laughter and applause. “You men of Athlone, you men who stand dressed in the uniforms of Sarsfield, on you devolves a very high duty,” Mac Eoin continued. Invoking the memory of Sergeant Custume, he invited his audience to look back at the heroic defence of Athlone in 1691, when Custume sacrificed his life in defence of the town bridge – “We go on in the scene and look as it were on the moving pictures” – as if they watching a movie.

“We see Sergeant Custume and the plain Volunteer making their brave struggle on that old bridge,” Mac Eoin said. “We see them tearing plank after plank and firing shot after shot until the last plank went down the river forever.” Just as those plain Volunteers of yesteryear had held out for Athlone, now the plain Volunteers of today held Athlone for Ireland.

Mac Eoin smiled as he took in the rapturous cheers for the stirring images he had conjured for his listeners. “It is up to us now to maintain the high ideals of Custume and his men. As it has come to our hands once more, through no carelessness will it be lost. We have it and we will hold it!”

After the applause had died down, Mac Eoin requested the civilians present to leave the barracks at the end of the ceremony. He then held up a document that he said made him responsible for the property here. When things in Ireland were properly settled, Mac Eoin promised, he would invite the people in and let them go where they pleased.

Mac Eoin and his staff proceeded to the Castle. He climbed up on the ramparts, where he hoisted the tricolour on the yacht-mast that had been provided beforehand, the previous flagstaff having been cut down by the British garrison in a case of imperial sour grapes.

As he did so, his soldiers stood to attention, the officers saluted on the square below and a guard of honour fired three volleys as a salute amidst the continuous cheering of those civilians who had ignored the instructions to leave, instead climbing up on the castle and throwing their caps in the air with wild abandon.

To Fight or Not to Fight

Unperturbed by the carnival atmosphere beneath him, Mac Eoin called out to the crowd to say that it was over three hundred years since an Irish flag had been hauled down from amidst shot and shell. The flag of Ireland was being unfurled that day, also under fire, and they meant to keep it there.

After descending from the Castle, Mac Eoin was met by representatives from the Athlone Urban Council and the local Sinn Féin Club. He accepted the complimentary addresses from each group on his own behalf and that of the Army. After hearing so much praise, he expressed the hope that “I will not suffer from vainglorious thoughts or a swelled head.”

When the Sinn Féin delegates congratulated him on his vote for the Treaty, Mac Eoin said that: “Were it not for the ratification of the Treaty this a day we would not see, or perhaps ever see.”

In response to those who believed that they should have continued to fight, Mac Eoin compared his stance to another of his sixteen months ago as he stood on the hill of Ballinalee, Co. Longford, in November 1920 at the head of his flying column:

On that morning a small party of us met a large party of the enemy that came to burn the town. We fought them a certain distance and I decided before going another round to keep cool. To fight that other round meant that they would stay and I would have to go. By not fighting it out I knew that we would remain and they would have to go. That is what has occurred as regards the Treaty.

No doubt, we can fight another round, but the chances are when we fight it that we go and they stay. As it is, we stay, we go. That is the test as to who has won. We hold the field where the fight was fought and therefore the victory is ours.

And with that, Mac Eoin and his staff returned to their barracks, their men following suit. The soldiers were allowed out later that evening, their green uniforms being much admired by the crowds that continued to fill the streets.[20]

Maintaining Athlone

The good will did not last long. A little under a month since claiming Athlone in the name of the Irish nation, Mac Eoin was forced to defend it for the sake of its new government.

He had left for Dublin to report on the local situation, which he considered serious enough for him to warn his acting commander, Kit McKeon, to take care in his absence. Upon returning, Mac Eoin met with McKeon who opened the reunion with: “I have held the barracks for you until this moment and I hand it over to you.”

Before Mac Eoin could reply, he heard shouting from outside the barracks. Looking out, he saw six of his officers with revolvers drawn, standing in a line in the square between the armoury and a group of agitated soldiers.

Mac Eoin acted quickly, calling out: “Fall in all ranks; officers take posts.” As he remembered:

Thank God they all fell in, and then I knew I could hold the Barracks in Athlone for the elected Government in Ireland. I addressed them, pointing out that Athlone was once again in Irish hands.

Mac Eoin pointed out the last time Athlone was in Irish hands was when Sergeant Custume and his eleven men tried and vain to hold the bridge in 1691 and died.

I pointed out that they were the successors of Custume and his men, but they could do more than Custume; they could hold Athlone. This was well received, and I then called each officer by name, putting him the question – was he prepared to serve Ireland and the Government, and obey my orders.

The first officer Mac Eoin called was Patrick Morrissey, who he had recently appointed as Athlone Brigade O/C. When confronted with the question, Morrissey replied that he was prepared to obey Mac Eoin’s orders but not those of the Government. Mac Eoin stressed to him and the others to note well that the only orders he would give were on the authority of the Government.

Backed into a corner, Morrissey made his choice clear: “Then I will not obey.”

That was enough for Mac Eoin. Wasting no further time, he stripped Morrissey of his rank and had him ejected from the barracks. He next went down the line of officers, putting the same question to each in turn. By the end, he was left with three officers from the Leitrim and Athlone brigades, standing in front of their respective companies.

He repeated the same question to them all, rankers and privates alike. Only after they had answered that they were prepared to obey and serve both the Government and Mac Eoin did he dismiss them to their billets. It was then, in Mac Eoin’s opinion, that:

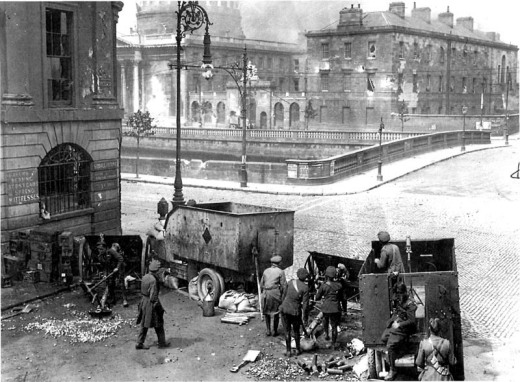

The Civil War was started. I had then no doubts about it, and the more I see of the whole position since then the more convinced I am that “the Civil War was on” and not of the Government’s or my making.

The opponents of the Treaty in the Four Courts and many Fianna Fáil supporters and writers today still assert that the “Civil War” began with the National Army attacking the Four Courts.

This is absolutely incorrect. The action by the National Forces at the Four Courts was the action of the Irish Government to end the Civil War and was, therefore, the beginning of the end.[21]

As steadfast as Mac Eoin’s performance had been that day, it had not been enough to hold over 80 of the 100 men from the Leitrim Brigade who deserted the following night. At least they had had no weapons to take with them, Mac Eoin having made the precaution of posting men from his native Longford over the armoury.

In his later notes, Mac Eoin called his men “soldiers-Volunteers.” It is an apt phrase, indicating men who were still in the transition between the IRA – part militia and part guerrilla force – and a professional army. In Athlone that day, this inability to reconcile the independence of the old and the demands of the new had threatened to be catastrophic.

The West Awakens

The situation remained perilous. The anti-Treaty IRA held the eastern half of Athlone by occupying a few shops there. Mac Eoin was sufficiently aggrieved to move against them:

As they seized private property, I exercised the power vested in me to protect life and property in my area. I won’t weary you with how I did it, suffice to say, that I put them out of the shops without loss of life.

That these rival posts were positioned to cut off lines of communication with Dublin was as much a motivation for their removal as respect for private property. The manager of the Royal Hotel argued for retaining the Anti-Treatyites lodged there since they were, after all, paying customers. To eject them would be interfering with his business.

Mac Eoin was persuaded to leave these particular guests be on condition that they did not stop or hinder public transport through the town or put up any sentries or further military installations. The Anti-Treatyites agreed and remained until a bloody incident in Athlone on the 25th April forced Mac Eoin’s hand. In the meantime, Mac Eoin had more than just Athlone to worry about, as the turmoil further west was demanding his attention.[22]

A pro-Treaty meeting planned for Easter Sunday in Sligo town had become the flashpoint between the hostile sides. Arthur Griffith was due to talk in the town which was rapidly starting to resemble an armed camp with a number of Anti-Treatyites occupying buildings such as the town hall, the post office and the courthouse. Compounding the tension were the party of pro-Treaty men who had arrived one night in an armoured car and taken up residence in the jail.

“The scenes are truly warlike,” wrote the Sligo Independent, at this point still referring to both factions as the IRA, the Pro-Treatyites being the ‘official’ IRA and their counterparts as the ‘unofficial’ one.

The latter faction seemed to be the dominant one. Its commander, Liam Pilkington, had recently posted a proclamation that prohibited all local public meetings, ostensibly on the grounds of public order. Caught in the middle of an already tense situation, the town authorities sent a telegram to Griffith, cautiously asking if his talk was still going ahead.

Griffith swiftly sent back an implacable reply:

Dail Eireann has not authorised, and will not authorise, any interference with the rights of public meeting and free speech. I, President of Dail Eireann, will go to Sligo on Sunday night.

Mac Eoin, too, was not to be moved, especially on the question of who held the military power in the area:

As Competent Military Authority of Mid-Western Command, I know nothing of Proclamation.

And that was that. If the Sligo authorities had hoped Griffith and Mac Eoin would take the hint and cancel the event, thus saving the town from the risk of becoming even more of a battleground, then they were sorely disappointed.[23]

The Sligo Situation

The meeting went ahead as planned, largely without bloodshed – largely.

Sligo seethed with activity in anticipation of Griffith’s arrival, with men from both factions of the IRA piling their sandbags, barricading the windows of billets and obtaining a worryingly large amount of field dressings and other first-aid appliances from the local chemists.

Griffith arrived at Longford Station on the evening of the 16th April where he was met by Mac Eoin, accompanied by a guard of honour with fixed bayonets on rifles. After a speech by Griffith from the train, they continued on to Sligo, arriving there on Saturday after 6 pm and joining the rest of the pro-Treaty forces based in the jail.

Other visitors to the town would have found accommodation scarce, as many hotels were already filled with young men from the ‘unofficial’ IRA who stood to attention in the hallways, holding their weapons – mostly shotguns, with an assortment of rifles and revolvers – and dressed in civilian attire save for a few uniformed officers. They had been coming to Sligo in intervals all day, also by train.

It was not just the Anti-Treatyites who were receiving reinforcements. The next day, at about 11 am, three lorries with about forty men from the ‘official’ IRA drove through the town, cheering and shouting, having come all the way from the Beggar’s Bush Barracks in Dublin. In contrast to their ‘unofficial’ counterparts, they went fully uniformed while equipped with service rifles, holding them at the ready. Some of them pulled up before the Imperial Hotel and the rest continued to Ramsay’s Hotel, about fifty yards down, both premises being in anti-Treaty hands.

Shots were fired in front of the two hotels. Which side had done so first was impossible to tell. The Anti-Treatyites received the worst of it, with three wounded, one in the neck, though there were no fatalities. The Free Staters drove away in their lorries, being cheered by the large crowd that had gathered at the sound of battle.

Shortly afterwards, General Pilkington sent word to General Mac Eoin, asking for a parley. Mac Eoin replied that he was willing to meet on the condition that the Anti-Treatyites evacuated the post office since that belonged to the Dáil as government property.

Mac Eoin had cut a commanding figure as he strode through the town earlier that morning, fully armed and unconcerned by the armed sentries staring out of fortified windows as he passed. He was not going to spoil the impression he made by agreeing too readily to talk, and negotiations withered on the vine when Pilkington refused to withdraw from the post office as demanded.

There was still the matter of three pro-Treaty soldiers who had been captured at the Imperial Hotel during the shootout there. When Mac Eoin came to demand their release, along with the return of their munitions, the Anti-Treatyite officer in charge meekly acquiesced.

Success in Sligo

This set the tone for the rest of the day, which belonged to the Pro-Treatyites. Despite their numbers, the neutered Anti-Treatyites made no move or protest as a parade of cars, each flying a tricolour, slowly made their way through the streets to the town centre. Mac Eoin led the procession, one hand holding a revolver and the other on the turret of the armoured car at the front. This vehicle was positioned in the town centre near the post office, its gun trained in an unsubtle warning on the building the ‘unofficial’ IRA had refused to vacate.

As before, Mac Eoin’s war record served as a statement in itself. Alderman D.M. Hanley introduced the general as someone whose name was known and honoured from one end of the country to the other. He was the man who had fought the Black-and-Tans and not from under his bed, Hanley continued, in what was a similarly unsubtle jab at the young men who made up much of the ‘unofficial’ IRA currently in Sligo. And who could fail to admire a man who treated a captured and wounded enemy fairly, honourably and decently (a reference to the captured Auxiliaries Mac Eoin had spared after the Clonfin Ambush of February 1921)?

After the applause to this glowing introduction, Mac Eoin spoke. While the other speakers, such as Griffith, used as a platform the same car that had carried them to the meeting, Mac Eoin called down from a window overlooking the town centre.

He was there as a soldier, not to argue for or against the Treaty, he said (somewhat disingenuously), but to uphold the freedom of speech and the sovereignty of the Irish people. The Army must be the servant, not the dictator of the people. It must be the people’s protection from foes within and without.

As in the Dáil, Mac Eoin’s speech was short and unpretentious, saying no more than necessary. But then, his name and reputation were enough to do his talking for him. One of the subsequent orators, Thomas O’Donnell TD, praised him as the one who had taken arms from policemen when they had arms, as opposed to those Anti-Treatyites who were shooting policemen now and somehow thinking themselves better patriots than Seán Mac Eoin.

The general continued to lead by example. When the meeting came to a close, a dozen pressmen decided to drive to Carrick-on-Shannon to make their reports, the telegraph wires in Sligo having been cut to make communication from there impossible. Mac Eoin escorted them in his armoured car. Coming across a blockade of felled trees across the road, Mac Eoin threw off his heavy military overcoat and set to work clearing the way with a woodman’s axe.[24]

A Death in Athlone

The rally in Sligo had been a resounding success but Mac Eoin had scant time to savour the triumph. Back in Athlone, the simmering tensions finally boiled over in the early hours of the 25th April. Mac Eoin was retiring for the night when, sometime after midnight, he heard about four shots nearby. He sprang out of bed, picking up the revolver at hand on a table before opening the window. He leaned out in time to see men running by.

“Who goes there?” Mac Eoin called.

“A friend” came the cryptic reply before the strangers disappeared.

Mac Eoin hurried outside to find three of his men, with another lying on the ground, his head in a spreading pool of blood. The stricken man, Brigadier-General George Adamson, was rushed to the military hospital where he died. The other men on the scene told of how they had been walking down the street when they found themselves surrounded by an armed party, whom of one had shot Adamson through the ear before fleeing.

Adamson’s death hit his commander hard. At the funeral two days later, before a crowd of ten thousand, a “visibly affected” Mac Eoin, according to a local newspaper, “delivered a short oratory at the graveside, and paid a glowing tribute to the many qualities of the deceased.”[25]

Mac Eoin had little doubt as to the motivation behind the killing. Adamson had been among those who had remained loyal from the outset during the attempted mutiny that Mac Eoin had quelled in Athlone Barracks. As Mac Eoin told the Pensions Board in 1929, as part of his recommendation for financial assistance to Adamson’s bereaved mother: “The rest of the officers of the Brigade who had turned Irregular always regarded Adamson as a traitor, that he let them down by his action at the meeting.”[26]

Mac Eoin decided that enough was enough. The anti-Treaty men in Athlone were taken into custody when their garrison in the Royal Hotel was surrounded by pro-Treaty soldiers. Conditions for them and subsequent POWs in Athlone Prison were harsh, with meagre food, a lack of fresh clothing and overcrowding in the cells.[27]

This, and that they were being detained without charge or trial, was of little consequence to Mac Eoin, who was in no mood for legal niceties. As far as he was concerned, he had allowed his enemies to remain at liberty and lost a valued soldier as a result.

Securing the Midlands

Not one to for half-measures, Mac Eoin moved to mop the remaining opposition nearby, by ordering the seizure of enemy posts in Kilbeggan and Mullingar. Assigned to the former, Captain Peadar Conlon drove there with two Crossley Tenders full of men on the 1st May. When the demand to surrender was refused by the anti-Treaty garrison in the Kilbeggan Barracks, Conlon issued an ultimatum that he would attack in ten minutes unless they cleared out.

While waiting, Conlon had the building surrounded. When the ten minutes were up, the besieged men called out to say that they would leave as long as they could retain their arms, ammunition and everything else inside. Conlon agreed to let them keep their weapons but all other items in the barracks were to stay.

When that was refused, Captain Conlon gave then another two hours, after which the Anti-Treatyites, hoping to drag out the situation, asked if they could be allowed to remain until the next morning. Conlon refused and again repeated his threat to attack, this time to do so immediately. The garrison caved in at that and departed, leaving behind the furnishings as demanded.

At Mullingar, the Anti-Treatyites did not go so quietly. Two of them had been arrested by Free Staters on the 25th April. When it seemed like they would resist, a couple of shots were fired at the ground to dissuade them. Getting the hint, the rest of their comrades evacuated Mullingar Barracks a week later on the 3rd May.

Later that night, an explosion ripped through the building. The fire brigade brought hoses to combat the flames enveloping the barracks and managed to save the adjacent houses, but with the barracks left a smouldering ruin. One of the former garrison later related to historian Uinseann MacEoin how he and another man had set the explosives in the barracks after the rest of the Anti-Treatyites had left.[28]

Regardless of the damage, Mac Eoin could report a victory. Lines of communication with Dublin were re-established, allowing the fledgling Free State a firmer hold on the Midlands.[29]

Squabbles in the Dáil

Back in Dublin, Mac Eoin returned to a Dáil forced to confront the depth of animosity inflicting the country. In addition to the death of Adamson and the subsequent fighting in the Midlands, pro and anti-Treaty forces had clashed in Kilkenny City on the 2nd May and did not stopped until the following day when the Anti-Treatyites were effectively expelled from the town.

The Dáil chambers listened to a report that eighteen men had been killed in Kilkenny – actually, there had been no fatalities, despite a number of injuries – which convinced many on both sides of the divide that enough was enough.

But not all agreed on the solution.

Mac Eoin listened incredulously to the talk of how peace needed to be made at once. On the contrary, Mac Eoin felt that the situation on the ground was too far gone for soft touches. The strong arm of the law was needed, and his men should be allowed to fulfil such a role. As he told the chamber in whose name he had been acting:

At present it may be difficult to arrange a truce in some particular instances. Men are engaged in the pursuit of men charged with serious offences, and justice demands that certain things be done. It would be difficult to stop men out at the moment to cause arrests for these incidents.

Here, de Valera got his second wind. Minutes before, he had been humbly promising to do his best to make his IRA allies see sense, while all but admitting his powerlessness over them. Now, de Valera tried to regain some face by singling out one of the opposition facing him from the benches on the grounds of propriety:

De Valera: Is Commandant Mac Eoin speaking as a member of the House or in a military capacity? If this matter is to be raised it must be arranged with the Chief of Staff and not with a subordinate officer.

Mac Eoin: I think I should speak without being interrupted by anybody – I do not care who it is. When I am here I am a member of the House. When I am in the field, I am a soldier and do not you forget it – or any other person. I am speaking from information at my disposal that such is the case. If you want me to act as a soldier, I can go outside and I will tell you.

De Valera: I suggest that any information Commandant Mac Eoin has had better be given to the Chief of Staff. My suggestion is that the Chief of Staff and the Chief Executive Officer get together and arrange a truce. It is for them to get information from their subordinate officers as to their conditions.

As Mac Eoin’s temper sizzled against de Valera’s glacial disdain, Collins waded in on the former’s side: “Lest there should be any misunderstanding, I take it that no one member of this House is censor over the remarks of another member of this House.”[30]

An Impossible Situation

Mac Eoin was to claim, years later, that a prominent Fianna Fáil supporter had said to him: “Thank God you won the Civil War, but we won the aftermath by talking and writing you out of the fruits of your victory. We have the fruits of your success. I shudder to think of what would have happened if we won the Civil War.”[31]

Whether or not someone had crossed party lines to actually say such a thing, it encapsulates perfectly Mac Eoin’s own attitudes. Sometime in the 1960s, he put his thoughts and memories of that turbulent era to paper. A memoir was intended, though one never materialise.

All the same, his notes and rough drafts do offer insight into what it must have been like to have been in the passenger seat, helpless to do anything but watch as the country, slowly at first but with rapid acceleration, slide into another war, this time between former comrades.

At the start of May, Mac Eoin found himself part of a 10-person group, appointed by the Dáil to discuss the best way out of the impasse. Five represented the anti-Treaty side – Kathleen Clarke, P.J. Ruttledge, Liam Mellows, Seán Moylan and Harry Boland – and the other half for the Free State in the persons of Seán Hales, Pádraic Ó Máille, Séamus O’Dwyer, Joseph McGuinness and Mac Eoin.

It was an experience Mac Eoin would remember with profound horror.

Held in the Mansion House, the talks would begin well enough, with progress made until a member of the anti-Treaty delegation arrived late, forcing the others to explain everything to him. As often as not, the newcomer would not agree with what had already been settled, and the talks would have to start all over again, until an hour or so later when another tardy delegate came to send everything back to stage one.

Mac Eoin put the blame for the habitual tardiness on the opposing side – only Kathleen Clarke was consistently on time – unsurprisingly so, perhaps, though there is no reason to doubt the strain he felt: “This was exasperating…To me, it was an impossible situation.” His time as a guerrilla leader had ill-prepared him for such frustrations: “I had never met anything like it before.”[32]

At the same time, a similar set of meetings were held elsewhere in the building, in the Supper Room, which also included Mac Eoin, along with Eoin O’Duffy, Gearóid O’Sullivan for the Pro-Treatyites, and Liam Lynch, Seán Moylan and – again – Mellows on the other side. Mac Eoin was obliged to go back and forth between two conferences, dressed in his new green uniform and with a revolver in his belt.

Vera McDonnell, a stenographer in the Sinn Féin Office, was assigned to take notes for the Dáil committee. She came to suspect that the presence of so many IRA leaders in the same building may have deterred the committee members from coming to any decisions on the basis that it would be the Army having the final say in any case.

She remembered a frustrated Mac Eoin being driven to tell them that surely they had enough brains to make their judgements, unless they wanted to wait until he came back from the other meeting. McDonnell thought this was very funny, though it is unlikely that Mac Eoin did as well.[33]

In any case, all the talks were to no avail. In a joint declaration read out to the Dáil by its Speaker, Eoin MacNeill, on the 10th May, Kathleen Clarke and Séamus O’Dwyer admitted that, despite extensive dialogue during the course of eleven meetings since the 3rd May to find a common basis for agreement: “We have failed.”

The laconic report was met with dread from those in attendance, the implications of such failure all too clear. Only Mac Eoin seemed unperturbed as he left the chamber, wearing an oddly benign smile.[34]

Pointing Fingers

The problems in the country were not limited to such futile talk shops. Like many in the IRA who had risked their lives against the British, he had a strong contempt for those who had only joined up after the Truce, once the immediate danger of a Tan raid or a police arrest had passed.

In Mac Eoin’s opinion, these ‘Trucateers’ brought nothing but trouble:

They were critical of the Officers and Volunteers who bore the brunt of the Battle prior to the Truce; they were very aggressive and militant at this time and in many places they were, by their actions, guilty of breaches of the Truce on the Irish side and were anxious to show their ability now. They were all ambitious for promotion, and this was something unknown in our ranks before the Truce.[35]

At the same time, the problem did not lie entirely with the recruits, as far as Mac Eoin was concerned, for the old hands could be equally troublesome. Rory O’Connor and John O’Donovan, both Anti-Treatyites, found themselves in charge of the newly-formed Departments of Chemistry and Explosives respectively.

As their responsibilities were yet untried, both, according to Mac Eoin, were eager for war to resume:

I believe this was one of the major causes (of course, there were others) of the Civil War. They felt that they should have been allowed to test their new inventions against the British. They tested them during the Civil War against ourselves, and they were a failure.[36]

Such opinions are coloured, of course, with the lingering bitterness that characterised so much of the country after the Civil War. As history, they are debatable. As insight into the attitudes and prejudices of the times, they are invaluable.

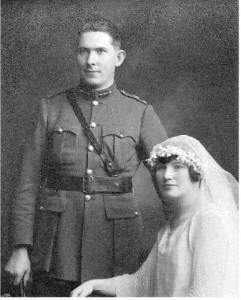

A Longford Wedding

Somehow Mac Eoin found the time for more personal matters. He wedded Alice Cooney on the 21st June in Longford town, the streets of which were hung with bunting and tricolours by people eager to honour a native son and war hero. When one of the many cars thronging the streets parked in front of St Mel’s Cathedral, Collins and Griffith stepped out together, to be promptly lit up by camera flashes. Eoin O’Duffy was also present, and the three Free Sate leaders signed as the witnesses to their colleague’s wedding.

Collins in particular was noted to be in boyish good spirits in the company of his friend. He would later come to the rescue when the groom had forgotten the customary gold coin to be used in the wedding by providing one of his own. Other officers from the numerous divisions and brigades in the pro-Treaty forces were in attendance, along with members of the old Longford Flying Column who saluted Mac Eoin outside the Cathedral as their former commander passed by.

Public interest did not end at the door. More people packed the Cathedral, some even standing on the aisle seats for a better view. Cameras were ever present, in the hands of local people as well as the ubiquitous pressmen, one of whom – untroubled by sacrilege – was resting his camera on a church candelabrum as he snapped away for posterity.

But possibly the most remarkable feature of the event was the present from Mrs McGrath, the bereaved mother of Thomas McGrath, the policeman for whose slaying seventeen months ago Mac Eoin had been sentenced to death and only narrowly reprieved. Mrs McGrath also sent a card wishing the newlyweds every possible happiness and good fortune. If a mother who had lost a son could make such a gesture, then perhaps there was hope for the country.[37]

Or perhaps not.

A Return to Sligo

Mac Eoin enjoyed his honeymoon in the North-West, though even that proved eventful when his car accidentally ran into a ditch. He sent out a telegram to Joseph Sweeney, the senior Free State officer in Donegal, for help in rescuing the vehicle. When that was done, Sweeney took the opportunity of putting on a parade for his esteemed visitor in Letterkenny on the 28th June.

Sweeney was marching down the main street with the rest of the men when a courier reached him with a message to pass on to Mac Eoin: the Four Courts, the headquarters of the Anti-Treatyites in Dublin, had been under attack since that morning. The long-dreaded fratricidal war had finally come about.[38]

Galvanised by this shocking news, Mac Eoin made it to Sligo town. The police barracks there was ablaze, its anti-Treaty garrison having pulled out in the early hours of the morning before torching it and the adjoining Recreation Hall in a ‘scorched earth’ tactic. Civilians who tried to reach the Town Hall where the fire-hose was kept were turned back at gunpoint by those same arsonists.

Mac Eoin was not so easily deterred. He marched to the Town Hall, a squad of his soldiers in tow, and returned to the barracks with the fire-hose in hand. Seeing that the Barracks and Recreation Hall, both burning fiercely, were beyond help, Mac Eoin instead turned the water on the neighbouring buildings.

It took three hours for the barracks to burn, during which a number of bombs carelessly left behind inside were heard exploding. By the time the flames died down, the two buildings were ruined shells, but the rest of the town was safe, from the fire at least. Mac Eoin, along with some local men, earned praise from the Sligo Independent “for their fearless work” in fire-fighting.[39]

Putting out the war, however, was not to be so readily done.

References

[1] Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922, 06/01/1921, p. 23. Available from the National Library of Ireland, also online from the University of Cork: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/E900003-001.html

[2] De Burca, Padraig and Boyle, John F. Free state or republic?: Pen pictures of the historic treaty session of Dáil Éireann (Dublin: The Talbot Press, 1922), p. 11

[3] Debate on the Treaty, pp. 23-4

[4] Seán Mac Eoin Papers, University College Dublin Archives, P151/80

[5] De Burca, Padraig and Boyle, John F. Free state or republic?, p. 11

[6] Irish Times, 20/12/1921

[7] Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, p. 134

[8] Ibid, p. 314

[9] Irish Times, 09/01/1922

[10] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/79

[11] Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), p. 168

[12] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/124

[13] Ibid, P151/162

[14] Irish Times, 27/08/1921

[15] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/1786

[16] Ibid, P151/1835

[17] Ibid, P151/1837

[18] Debate on the Treaty, pp. 424-5

[19] Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Fontana/Collins, 1970), p. 235

[20] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/131

[21] Ibid, P151/1809

[22] Ibid, P151/1812

[23] Sligo Independent, 15/04/1922

[24] Ibid, 22/04/1922

[25] Westmeath Guardian, 28/04/1922

[26] Adamson, George (Military Archives, 2/D/2,) http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/docs/files//PDF_Pensions/R3/2D2GEORGEADAMSON/W2D2GEORGEADAMSON.pdf (Accessed 03/05/2017), p. 131

[27] Irish Times, 01/05/1922

[28] Westmeath Guardian, 28/04/1922, 05/05/1922 ; Irish Times, 01/05/1922 ; MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980), p. 375

[29] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/1812

[30] Dáil Éireann. Official Report, August 1921 – June 1922 (Dublin: Stationery Office [1922]), p. 368

[31] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/1812

[32] Ibid, P151/1813 ; Irish Times, 01/05/1922

[33] McDonnell, Vera (BMH / WS 1050), pp. 9-10

[34] Irish Times, 10/05/1922

[35] Mac Eoin Papers, P151/1804

[36] Ibid

[37] Longford Leader, 24/06/1922

[38] Griffith, Kenneth and O’Grady, Timothy. Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1998), p. 287

[39] Sligo Independent, 08/07/1922

Bibliography

Books

Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010)

Dáil Éireann. Official Report, August 1921 – June 1922 (Dublin: Stationery Office [1922])

Debate on the Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed in London on the 6th December 1921: Sessions 14 December 1921 to 10 January 1922. Available from the National Library of Ireland, also online: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/E900003-001.html

De Burca, Padraig and Boyle, John F. Free state or republic?: Pen pictures of the historic treaty session of Dáil Éireann (Dublin: The Talbot Press, 1922)

Griffith, Kenneth and O’Grady, Timothy. Curious Journey: An Oral History of Ireland’s Unfinished Revolution (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1998)

MacEoin, Uinseann, Survivors (Dublin: Argenta Publications, 1980)

Younger, Calton. Ireland’s Civil War (Fontana/Collins, 1970)

University College Dublin Archives

Seán Mac Eoin Papers

Newspapers

Irish Times

Longford Leader

Sligo Independent

Westmeath Guardian

Military Service Pensions Collection

Adamson, George (Military Archives, 2/D/2,) http://mspcsearch.militaryarchives.ie/docs/files//PDF_Pensions/R3/2D2GEORGEADAMSON/W2D2GEORGEADAMSON.pdf (Accessed 03/05/2017)

Bureau of Military History Statement

McDonnell, Vera, WS 1050

Robinson’s contention was that Breen had falsely made several claims about his role in the War of Independence through his 1924 memoir, My Fight for Irish Freedom. It was a case he would make repeatedly, in his Statement and in the numerous letters he wrote to various newspapers or individuals and later collected in the appendix of his Statement.

Robinson’s contention was that Breen had falsely made several claims about his role in the War of Independence through his 1924 memoir, My Fight for Irish Freedom. It was a case he would make repeatedly, in his Statement and in the numerous letters he wrote to various newspapers or individuals and later collected in the appendix of his Statement.

Equally questionable is Ambrose’s suggestion as to why Robinson added these letters to the appendix of his BMH Statement: “The result was a time bomb from another era, recently exploded, that was designed to wipe out Breen’s reputation and the credibility of his book.”

Equally questionable is Ambrose’s suggestion as to why Robinson added these letters to the appendix of his BMH Statement: “The result was a time bomb from another era, recently exploded, that was designed to wipe out Breen’s reputation and the credibility of his book.” One possible lesson to take from this book is that politics is something best left to politicians. Shortly after the 1957 electoral defeat of John A. Costello’s second and final coalition government, the former Taoiseach was walking along the Dublin quays with two other senior Fine Gael men, James Dillon and Patrick Lindsay.

One possible lesson to take from this book is that politics is something best left to politicians. Shortly after the 1957 electoral defeat of John A. Costello’s second and final coalition government, the former Taoiseach was walking along the Dublin quays with two other senior Fine Gael men, James Dillon and Patrick Lindsay.